David Roth Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Czechoslovak-Polish Relations 1918-1968: the Prospects for Mutual Support in the Case of Revolt

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1977 Czechoslovak-Polish relations 1918-1968: The prospects for mutual support in the case of revolt Stephen Edward Medvec The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Medvec, Stephen Edward, "Czechoslovak-Polish relations 1918-1968: The prospects for mutual support in the case of revolt" (1977). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5197. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5197 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CZECHOSLOVAK-POLISH RELATIONS, 191(3-1968: THE PROSPECTS FOR MUTUAL SUPPORT IN THE CASE OF REVOLT By Stephen E. Medvec B. A. , University of Montana,. 1972. Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1977 Approved by: ^ .'■\4 i Chairman, Board of Examiners raduat'e School Date UMI Number: EP40661 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity VOLUME 6: WAR and PEACE, SEX and VIOLENCE

The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity VOLUME 6: WAR AND PEACE, SEX AND VIOLENCE JAN M. ZIOLKOWSKI To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/822 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. THE JUGGLER OF NOTRE DAME VOLUME 6 The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity Vol. 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence Jan M. Ziolkowski https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Jan M. Ziolkowski This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Jan M. Ziolkowski, The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity. Vol. 6: War and Peace, Sex and Violence. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0149 Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. Copyright and permissions information for images is provided separately in the List of Illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

Extensions of Remarks 13895 Extensions of Remarks

May 22, 1995 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 13895 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS A SALUTE TO EDWIN L. ARTZT: TRIBUTE TO MR. EDUARDO J. REPUBLICAN WAR PROFITEERING: INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS TORRES COMMENTARY BY KEVIN PHILLIPS LEADER HON. FORTNEY PETE STARK HON. JOSE E. SERRANO HON. ROB PORTMAN OF CALIFORNIA IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF OHIO OF NEW YORK IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Monday, May 22, 1995 Mr. STARK. Mr. Speaker, the May 17 radio Monday, May 22, 1995 Monday, May 22, 1995 commentary by Kevin Phillips on the Repub Mr. PORTMAN. Mr. Speaker, I am pleased Mr. SERRANO. Mr. Speaker, on Friday, lican budget plan hit the nail on the head: today to recognize a prominent Cincinnatian, May 19, 1995, a group of dedicated public In the guise of crisis legislation, deficit re Edwin L. Artzt, on the occasion of his retire school educators gathered in my congres duction ... especially as put forward by the ment as chairman of the board and chief ex House of Representatives, also has major sional district to honor one of their distin ecutive officer of the Procter & Gamble Co. overtones of special interest favoritism and Today we thank him for the vision and service guished colleagues, Eduardo J. Torres, for his income distribution. that he has so generously given to his com years of service to the children of our district Spending on government programs, ... is pany and to his community. and indeed, the Nation, and on the occasion to be reduced in ways that principally bur of his retirement. den the poor and middle class while simulta Ed began his career with Procter & Gamble neously taxes are to be cut in a way that pre in 1953 in the sales-training department. -

Newsletter 2004/2

NEWSLETTER 2004/2 NEW SPACE FOR THE JEWISH MUSEUM’S ARCHIVE AND DEPOSITORY April 2004 saw the completion of the reconstruction of the synagogue in Smíchov-Prague 5, which will be used by the Jewish Museum in Prague for the storage of archive materials and as a depository for its art collections. The Jewish Museum in Prague spends a large part of its funds on the renovation of Jewish monuments. Since October 1994, when it became an independent Jewish institution, it has repaired and reconstructed eight large buildings, both in and outside Prague, including historic synagogues which it uses for exhibitions and specialised activities. The culmination of this work is the repair and reconstruction of the former Smíchov Synagogue, which was founded over 140 years ago. This project was entirely financed by the Jewish Museum in Prague. Throughout its existence the synagogue has undergone several building alterations; what was probably the most extensive reconstruction occurred in 1930. During the Nazi occupation the synagogue was closed down and converted into a warehouse for storing confiscated Jewish property. It was also used as a warehouse during the Communist era from the beginning of the 1950s. After the fall of the Communist regime, the devastated building was returned to the Jewish community in Prague and has been rented to the Jewish Museum in Prague since 1998. The first restoration work on the synagogue was carried out in 1999, but the bulk of the building activity was not undertaken until 2003. This project was financed entirely by the Jewish Museum in Prague with contributions in part from the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E 1090

E 1090 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks May 22, 1995 CONGRATULATIONS TO ATLANTIS CONGRATULATIONS TO FIRST OC- panic Educators Association, the Community COMMUNITY AND NORWEST CUPATIONAL CENTER OF NEW Service Award from the Association Civica BANK COLORADO JERSEY AND ITS HONOREES Arecibeno, the P.S. 5 Parent Teacher Asso- ciation Award, the Ramon S. Velez Scholar- HON. PATRICIA SCHROEDER HON. WILLIAM J. MARTINI ship Committee Leadership Award and the P.S. 5 Parent Teacher Association 20th Anni- OF COLORADO OF NEW JERSEY IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES versary Award. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Mr. Speaker, the residents of my district, Monday, May 22, 1995 Monday, May 22, 1995 Hispanic Americans everywhere, and indeed Mrs. SCHROEDER. Mr. Speaker, I want to Mr. MARTINI. Mr. Speaker, I would like to the entire Nation are the beneficiaries of such commend Atlantis Community Inc. and tell my colleagues about several very special lifelong dedication to the education of our Norwest Bank Colorado, both of Denver, for individuals whose excellent work in the area of youth, and in particular of those often-dis- launching one of the Nation's first home mort- occupational and rehabilitational therapy for advantaged youngsters who grow up in our gage financing and consumer loan programs the aged, the disabled, and the disadvantaged inner city communities. I ask my colleagues to for lower-income people with disabilities. has earned them high honors at the 41st anni- join me in conveying best wishes and deep On May 17, Social Compact recognized versary celebration and annual awards pres- gratitude to Mr. -

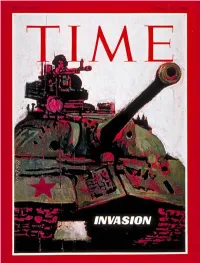

The Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia and the Crushing of the Prague Spring

The Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia and the crushing of the Prague Spring [20-08-2003] By Jan Velinger Listen 16kb/s ~ 32kb/s It has been thirty-five years since Soviet troops began entering Czechoslovakia late on August 20th and early August 21st in a carefully orchestrated invasion designed to crush the period of political and economic reforms known as the Prague Spring, reforms led by the country's new First Secretary of the Communist party Alexander Dubcek. A movement viewed by Leonid Brezhnev and other Soviet hard-liners in Moscow as a serious threat to the Soviet Union's hold on the Socialist satellite states, they decided to act. In the first hours on the 21st Soviet planes began to land unexpectedly at Prague's Ruzyne airport, and shortly Soviet tanks would roll through Prague's narrow streets. Within hours foreign troops would take up strategic positions throughout the city, including surrounding the building of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, taking hold of Wenceslas Square, and eventually taking over Czechoslovak radio and television. The occupation of '68 had begun. The tanks roll in Soviet tank in front of the Czechoslovak Radio building, photo: CTK "I was sleeping soundly when a friend from New York called me and said 'Have you evacuated the family?' I answered 'Why should I?' and he said 'Prague has been invaded, the airport has been seized, and the Castle is under Russian control..." American editor Alan Levy was a foreign correspondent in Czechoslovakia in 1968. On August 21st he witnessed some of the first tanks as they steered their way in to the Czech capital. -

Artists Marginalized by Own Revolution Monday, November 9, 2009 Natalia A

Artists marginalized by own revolution Monday, November 9, 2009 Natalia A. Feduschak THE WASHINGTON TIMES PRAGUE | Martin Putna stood next to his favorite poster at an exhibit that opened here recently celebrating the life of Vaclav Havel, the Czech playwright and former president who became the face of the peaceful revolution that brought down communist regimes throughout much of Eastern Europe 20 years ago. "Being in power makes me permanently suspicious of myself," reads the caption on the poster, which shows a smiling Mr. Havel sitting on an ornately decorated chair. A tagline notes that Mr. Havel made the statement in 1991, when he was awarded a prize for outstanding contributions to European culture. Artists and other cultural figures played an outsized role in the demise of governments in the old Soviet satellites — a role that has diminished as societies have opened up to a freer interchange of ideas with the rest of the world. Under communism, mimeographed manuscripts known in Russian as "samizdat" or self- published works, passed from hand to hand to avoid the censors. Other works were smuggled out to the West for publication. Western culture, from modern art to heavy- metal music, was coveted forbidden fruit. The catalyst for the Charter 77 movement co-founded by Mr. Havel in 1977 was the arrest of a Czech psychedelic band known as the Plastic People of the Universe. The "velvet" revolution that remade Czechoslovakia in 1989 took its name from the Velvet Underground, a U.S. rock band that was a favorite of Mr. Havel's. The role that culture and literature played in Central and Eastern Europe was "bigger and more important than in the free world," said Mr. -

The Raul Hilberg Lecture on Reading a Document

The Raul Hilberg Lecture The University of Vermont November 2, 2005 On Reading a Document: SS-Man Katzmann’s “Solution of the Jewish Question in the District of Galicia” Claudia Koonz Duke University Two “snapshots” of Raul Hilberg provide a glimpse of how this gifted historian worked with documents, the raw material of history. The first is from the late 1940s. Imagine Professor Hilberg as a graduate student beginning research on the Nazi extermination of the Jews at the War Documentation Project. There he stands, pondering 28,000 linear feet of mostly uncatalogued records. Many aspiring historians in this situation would have walked away, accepted their mentor‟s advice, and found a more conventional topic. But this particular historian stayed on (and on), methodically reconstructing the organization of the vast bureaucratic networks that converted a lethal antisemitic vision into a catastrophic fact. For our second glimpse of Professor Hilberg, we don‟t have to imagine, we can move fast forward to the mid-1980s and see him explaining how to read a one-page memo about railroad scheduling in the film Shoah. Speaking to Claude Lanzmann, the director, Hilberg emphasizes how vital it is to read not just its content but every facet of a document. Who wrote it? Who sent it? Who received the original and copies? What is on the subject line? Does it bear a red “TOP SECRET” stamp? Every aspect of a document “incorporates the whole culture and atmosphere of the time.” Administrative efficiency in mass murder or any other large scale operation depends 2 on bureaucrats never pondering the orders they follow. -

An American Jew in Vienna

An American Jew in Vienna by Alan Levy Editor-in-Chief The Prague Post Working Paper 00-2 © 2000 by the Center for Austrian Studies. Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from the Center for Austrian Studies. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the US Copyright Act of 1976. The the Center for Austrian Studies permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of the Center's Working Papers on reserve (in multiple photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses: teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce Center for Austrian Studies Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promotion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center. I. Aftermath of a Poll The awakening came in the morning paper two and a half years after we’d settled in Vienna–a three-column headline on page two of the Friday, November 9, 1973 morning edition of Kurier: "ARE 70% ANTI-SEMITES?" The subhead began to answer the question: "Only 30 Percent of Austrians Are Without Anti-Jewish Inclinations." A sociological institute based in Linz had used 197 researchers to interview 963 Austrians in one week–concentrating on five true-or-false statements: • • It would be better for Austria to be without Jews. • I would not marry a Jew. • When a Jew does something good, mostly he does it only out of calculation. -

The Life of Simon Wiesenthal As Told by the New York Times

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 4-16-2006 The Life of Simon Wiesenthal as Told by the New York Times Mary Cate Kelleher Salve Regina University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Kelleher, Mary Cate, "The Life of Simon Wiesenthal as Told by the New York Times" (2006). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kelleher 1 The Life of Simon Wiesenthal as Told by the New York Times By Mary Cate Kelleher ENG 490/02 Prepared for Dr. Donna Harrington-Lueker English Department Pell Scholars Honors Program Salve Regina University April 15, 2006 Kelleher 2 On Se ptember 21, 2005 The New York Times ran a front page article declaring the death of acclaimed Nazi -Hunter Simon Wiesenthal. The story, written by award -winning New York Times journalist Ralph Blumenthal, functioned both as an obituary and as a tribute to the late Holocaust survivor’s life. In it, Wiesenthal’s forty years in the public eye, filled with accomplishments and disappointments, controversy and criticism, encouragement and at times nonchalance, were honored nobly. Between the years of 1963 and 2003 The New York Times published seven -hundred thirty -one articles mentioning either Wiesenthal or the Center named for him in Los Angeles. -

The Whitney R. Harris Third Reich Collection : Materials Added to the Collection, 1999-June 30, 2008

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship University Libraries Publications University Libraries 7-2008 The Whitney R. Harris Third Reich Collection : materials added to the collection, 1999-June 30, 2008 Brian Vetruba Washington University in St Louis Shane D. Peterson Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/lib_papers Part of the European History Commons, Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Vetruba, Brian and Peterson, Shane D., "The Whitney R. Harris Third Reich Collection : materials added to the collection, 1999-June 30, 2008" (2008). University Libraries Publications. 29. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/lib_papers/29 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Libraries Publications by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Whitney R. Harris Third Reich Collection Materials Added to the Collection, 1999 — June 30, 2008 Compiled by: Shane D. Peterson (Student Assistant) Brian Vetruba (German Studies Librarian) Washington University Olin Library St. Louis, Missouri July 2008 Introduction to the Collection The Whitney R. Harris Third Reich Collection is a comprehensive collection on Germany from 1933 to 1945. It began in 1980 with a donation of funds, books, and documents from Whitney R. Harris, who played a key role in prosecuting Nazi war criminals during the Nuremberg trials in 1945-1946. His book Tyranny on Trial is recognized as the first significant study of Nuremberg and its legacy. -

Worcester Historical

Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies 11 Hawthorne Street Worcester, Massachusetts ARCHIVES 2019.01 Kline Collection Processd by Casey Bush January 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Series Page Box Collection Information 3 Historical/Biographical Notes 4 Scope and Content 4 Series Description 5 1 Antisemitic Material 7-15 1-2, 13 2 Holocaust Material 16-22 2-3, 13 3 Book Jackets 23 4-9 4 Jewish History material 24-29 10-11, 13 5 Post-war Germany 30-32 12 6 The Second World War & Resistance 33-37 28 7 French Books 38-41 14 8 Miscellaneous-language materials 42-44 15 9 German language materials 45-71 16-27 10 Yiddish and Hebrew language materials 72-77 29-31 11 Immigration and Refugees 78-92 32-34 12 Oversized 93-98 35-47 13 Miscellaneous 99-103 48 14 Multi-media 104-107 49-50 Appendix 1 108 - 438 2 Collection Information Abstract : This collection contains books, pamphlets, magazines, guides, journals, newspapers, bulletins, memos, and screenplays related to anti-Semitism, German history, and the Holocaust. Items cover the years 1870-1990. Finding Aid : Finding Aid in print form is available in the Repository. Preferred Citation : Kline Collection – Courtesy of The Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts. Provenance : Purchased in 1997 from Eric Chaim Kline Bookseller (CA) through the generosity of the following donors: Michael J. Leffell ’81 and Lisa Klein Leffell ’82, the Sheftel Family in memory of Milton S. Sheftel ’31, ’32 and the proceeds of the Carole and Michael Friedman Book Fund in honor of Elisabeth “Lisa” Friedman of the Class of 1985.