On the Syntax of Sentential Negation in Yemeni Arabic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Different Dialects of Arabic Language

e-ISSN : 2347 - 9671, p- ISSN : 2349 - 0187 EPRA International Journal of Economic and Business Review Vol - 3, Issue- 9, September 2015 Inno Space (SJIF) Impact Factor : 4.618(Morocco) ISI Impact Factor : 1.259 (Dubai, UAE) DIFFERENT DIALECTS OF ARABIC LANGUAGE ABSTRACT ifferent dialects of Arabic language have been an Dattraction of students of linguistics. Many studies have 1 Ali Akbar.P been done in this regard. Arabic language is one of the fastest growing languages in the world. It is the mother tongue of 420 million in people 1 Research scholar, across the world. And it is the official language of 23 countries spread Department of Arabic, over Asia and Africa. Arabic has gained the status of world languages Farook College, recognized by the UN. The economic significance of the region where Calicut, Kerala, Arabic is being spoken makes the language more acceptable in the India world political and economical arena. The geopolitical significance of the region and its language cannot be ignored by the economic super powers and political stakeholders. KEY WORDS: Arabic, Dialect, Moroccan, Egyptian, Gulf, Kabael, world economy, super powers INTRODUCTION DISCUSSION The importance of Arabic language has been Within the non-Gulf Arabic varieties, the largest multiplied with the emergence of globalization process in difference is between the non-Egyptian North African the nineties of the last century thank to the oil reservoirs dialects and the others. Moroccan Arabic in particular is in the region, because petrol plays an important role in nearly incomprehensible to Arabic speakers east of Algeria. propelling world economy and politics. -

A Note on the Genitive Particle Ħaqq in Yemeni Arabic Free Genitives Mohammed Ali Qarabesh, University of Albayda Mohammed Q

A note on ħaqq in Yemeni Arabic … Qarabesh & Shormani A Note on the Genitive particle ħaqq in Yemeni Arabic Free Genitives Mohammed Ali Qarabesh, University of Albayda Mohammed Q. Shormani, University of Ibb الملخص: تتىاوه هذي اىىرقح ميمح "حق" فٍ اىيهجح اىُمىُح ورتثتها اىىحىَح فٍ تزمُة إضافح اىمينُح اىتحيُيُح، وتقذً ىها تحيُو وحىٌ وصفٍ، حُث َفتزض اىثاحثان أن هىاك وىػُه مه هذي اىنيمح فٍ اىيهجح اىُمىُح: ا( تيل اىتٍ ﻻ تظهز ػيُها ػﻻماخ اىتطاتق، مثو "اىسُاراخ حق ػيٍ"، حُث وزي أن ميمح "اىسُاراخ" ىها اىسماخ )جمغ، مؤوث، غائة( وىنه ميمح "حق" ﻻ تتطاتق مؼها فٍ أٌ مه هذي اىصفاخ، و ب( تيل اىتٍ تظهز ػيُها ػﻻماخ اىتطاتق مثو "اىسُاراخ حقاخ ػيٍ" حُث تتطاتق اىنيمتان "اىسُاراخ" و"حقاخ" فٍ مو اىسماخ. وؼَزض اىثاحثان أن اىىىع اﻷوه َ ستخذً فٍ مىاطق مثو صىؼاء، ػذن، إب... اىخ، واىثاوٍ فٍ شثىج وحضزمىخ ... اىخ. وَخيص اىثاحثان إىً أن هىاك دىُو ػميٍ ىُس فقظ ػيً وجىد اىىحى اىنيٍ فٍ "اىمينح اىيغىَح" تو أَضا ػيً "تَ ْى َس َطح" هذا اىىحى، ىُس فقظ تُه اىيغاخ تو وتُه ىهجاخ اىيغح اىىاحذج. الكلمات المفتاحية: اىيغاخ اىسامُح، اىؼزتُح اىُمىُح، اىؼثزَح، اى م ْينُح، "حق" Abstract This paper provides a descriptive syntactic analysis of ħaqq in Yemeni Arabic (YA). ħaqq is a Semitic Free Genitive (FG) particle, much like the English of. A FG minimally consists of a head N, genitive particle and genitive DP complement. It (in a FG) expresses or conveys the meaning of possessiveness, something like of in English. There are two types of ħaqq in Yemeni Arabic: one not exhibiting agreement with the head N, and another exhibiting it. -

Arabic Sociolinguistics: Topics in Diglossia, Gender, Identity, And

Arabic Sociolinguistics Arabic Sociolinguistics Reem Bassiouney Edinburgh University Press © Reem Bassiouney, 2009 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh Typeset in ll/13pt Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and East bourne A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 2373 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 2374 7 (paperback) The right ofReem Bassiouney to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Contents Acknowledgements viii List of charts, maps and tables x List of abbreviations xii Conventions used in this book xiv Introduction 1 1. Diglossia and dialect groups in the Arab world 9 1.1 Diglossia 10 1.1.1 Anoverviewofthestudyofdiglossia 10 1.1.2 Theories that explain diglossia in terms oflevels 14 1.1.3 The idea ofEducated Spoken Arabic 16 1.2 Dialects/varieties in the Arab world 18 1.2. 1 The concept ofprestige as different from that ofstandard 18 1.2.2 Groups ofdialects in the Arab world 19 1.3 Conclusion 26 2. Code-switching 28 2.1 Introduction 29 2.2 Problem of terminology: code-switching and code-mixing 30 2.3 Code-switching and diglossia 31 2.4 The study of constraints on code-switching in relation to the Arab world 31 2.4. 1 Structural constraints on classic code-switching 31 2.4.2 Structural constraints on diglossic switching 42 2.5 Motivations for code-switching 59 2. -

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi To cite this version: Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi. Arabic and Contact-Induced Change. 2020. halshs-03094950 HAL Id: halshs-03094950 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03094950 Submitted on 15 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language Contact and Multilingualism 1 science press Contact and Multilingualism Editors: Isabelle Léglise (CNRS SeDyL), Stefano Manfredi (CNRS SeDyL) In this series: 1. Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). Arabic and contact-induced change. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language science press Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). 2020. Arabic and contact-induced change (Contact and Multilingualism 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/235 © 2020, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution -

Cognate Words in Mehri and Hadhrami Arabic

Cognate Words in Mehri and Hadhrami Arabic Hassan Obeid Alfadly* Khaled Awadh Bin Mukhashin** Received: 18/3/2019 Accepted: 2/5/2019 Abstract The lexicon is one important source of information to establish genealogical relations between languages. This paper is an attempt to describe the lexical similarities between Mehri and Hadhrami Arabic and to show the extent of relatedness between them, a very little explored and described topic. The researchers are native speakers of Hadhrami Arabic and they paid many field visits to the area where Mehri is spoken. They used the Swadesh list to elicit their data from more than 20 Mehri informants and from Johnston's (1987) dictionary "The Mehri Lexicon and English- Mehri Word-list". The researchers employed lexicostatistical techniques to analyse their data and they found out that Mehri and Hadhrmi Arabic have so many cognate words. This finding confirms Watson (2011) claims that Arabic may not have replaced all the ancient languages in the South-Western Arabian Peninsula and that dialects of Arabic in this area including Hadhrami Arabic are tinged, to a greater or lesser degree, with substrate features of the Pre- Islamic Ancient and Modern South Arabian languages. Introduction: three branches including Central Semitic, Historically speaking, the Semitic language Ethiopian and Modern south Arabian languages family from which both of Arabic and Mehri (henceforth MSAL). Though Arabic and Mehri descend belong to a larger family of languages belong to the West Semitic, Arabic descends called Afro-Asiatic or Hamito-Semitic that from the Central Semitic and Mehri from includes Semitic, Egyptian, Cushitic, Omotic, (MSAL) which consists of two branches; the Berber and Chadic (Rubin, 2010). -

00. the Realization of Negation in the Syrian Arabic Clause, Phrase, And

The realization of negation in the Syrian Arabic clause, phrase, and word Isa Wayne Murphy M.Phil in Applied Linguistics Trinity College Dublin 2014 Supervisor: Dr. Brian Nolan Declaration I declare that this dissertation has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and that it is entirely my own work. I agree that the Library may lend or copy this dissertation on request. Signed: Date: 2 Abstract The realization of negation in the Syrian Arabic clause, phrase, and word Isa Wayne Murphy Syrian Arabic realizes negation in broadly the same way as other dialects of Arabic, but it does so utilizing varied and at times unique means. This dissertation provides a Role and Reference Grammar account of the full spectrum of lexical, morphological, and analytical means employed by Syrian Arabic to encode negation on the layered structures of the verb, the clause, the noun, and the noun phrase. The scope negation takes within the LSC and the LSNP is identified and illustrated. The study found that Syrian Arabic employs separate negative particles to encode wide-scope negation on clauses and narrow-scope negation on constituents, and utilizes varied and interesting means to express emphatic negation. It also found that while Syrian Arabic belongs in most respects to the broader Levantine family of Arabic dialects, its negation strategy is more closely aligned with the Arabic dialects of Iraq and the Arab Gulf states. 3 Table of Contents DECLARATION......................................................................................................................... -

Modern Standard Arabic ﺝ

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture (Linqua- IJLLC) December 2014 edition Vol.1 No.3 /Ʒ/ AND /ʤ/ :ﺝ MODERN STANDARD ARABIC Hisham Monassar, PhD Assistant Professor of Arabic and Linguistics, Department of Arabic and Foreign Languages, Cameron University, Lawton, OK, USA Abstract This paper explores the phonemic inventory of Modern Standard ﺝ Arabic (MSA) with respect to the phoneme represented orthographically as in the Arabic alphabet. This phoneme has two realizations, i.e., variants, /ʤ/, /ӡ /. It seems that there is a regional variation across the Arabic-speaking peoples, a preference for either phoneme. It is observed that in Arabia /ʤ/ is dominant while in the Levant region /ӡ/ is. Each group has one variant to the exclusion of the other. However, there is an overlap regarding the two variants as far as the geographical distribution is concerned, i.e., there is no clear cut geographical or dialectal boundaries. The phone [ʤ] is an affricate, a combination of two phones: a left-face stop, [d], and a right-face fricative, [ӡ]. To produce this sound, the tip of the tongue starts at the alveolar ridge for the left-face stop [d] and retracts to the palate for the right-face fricative [ӡ]. The phone [ӡ] is a voiced palato- alveolar fricative sound produced in the palatal region bordering the alveolar ridge. This paper investigates the dichotomy, or variation, in light of the grammatical (morphological/phonological and syntactic) processes of MSA; phonologies of most Arabic dialects’ for the purpose of synchronic evidence; the history of the phoneme for diachronic evidence and internal sound change; as well as the possibility of external influence. -

Uncorrected Proofs - John Benjamins Publishing Company Doi 10.1075/Sal.4.07Akk © 2016 John Benjamins Publishing Company 154 Faruk Akkuş and Elabbas Benmamoun

Clause structure in contact contexts The case of Sason Arabic* Faruk Akkuş and Elabbas Benmamoun Yale University / University of Illinois In this paper, we discuss the syntax of negation in Sason Arabic which patterns with both its Arabic neighbors, particularly the so-called Mesopotamian varie- ties (such as the Iraqi variety/varieties of Mosul) and the neighboring languages that are typologically different, particularly Kurdish and Turkish. We provide a description of copula constructions in Sason and discuss their word order pat- terns and interaction with sentential negation. Depending on the nature of the predicate, Sason displays both head-initial word order, which reflects its Arabic and Semitic lineage, and head-final word order, which shows the influence of its head final neighbors and competitors for linguistic space. Keywords: Sason Arabic, language contact, clause structure, copula 1. Introduction Language contact is a fact of life for many languages. The difference has more to do with the degree of contact and the impact on the languages involved in the contact situation.1 The latter critically depends on the relative status and roles of the languages, the size of their speech communities, the domains of interaction between the languages, literacy and education, among many others.2 The most * We would like to thank the audience at the Annual Symposium on Arabic Linguistics 28 held at the University of Florida and the two anonymous reviewers for their comments and sug- gestions. We also thank the editors of this volume, Youssef Haddad and Eric Potsdam, whose suggestions improved the paper substantially. All errors are ours. -

Creating Resources for Dialectal Arabic from a Single Annotation: a Case Study on Egyptian and Levantine

Creating Resources for Dialectal Arabic from a Single Annotation: A Case Study on Egyptian and Levantine Ramy Eskander, Nizar Habash†, Owen Rambow and Arfath Pasha Columbia University, USA †New York University Abu Dhabi, UAE [email protected], [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Arabic dialects present a special problem for natural language processing because there are few Arabic dialect resources, they have no standard orthography, and they have not been studied much. However, as more and more written dialectal Arabic is found on social media, natural lan- guage processing for Arabic dialects has become an important goal. We present a methodology for creating a morphological analyzer and a morphological tagger for dialectal Arabic, and we illustrate it on Egyptian and Levantine Arabic. To our knowledge, these are the first analyzer and tagger for Levantine. 1 Introduction The goal of this paper is to show how a particular type of annotated corpus can be used to create a morphological analyzer and a morphological tagger for a dialect of Arabic, without using any additional resources. A morphological analyzer is a tool that returns all possible morphological analyses for a given input word taken out of any context. A morphological tagger is a tool that identifies the single morphological analysis which is correct for a word given its specific context in a text. We illustrate our work using Egyptian Arabic and Levantine Arabic. Egyptian Arabic is in fact relatively resource-rich compared to other Arabic dialects, but we use a subset of available data to simulate a resource-poor dialect. -

Croft's Cycle in Arabic: the Negative Existential Cycle in a Single Language

Linguistics 2020; aop David Wilmsen* Croft’s cycle in Arabic: The negative existential cycle in a single language https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2020-0021 Abstract: Thenegativeexistentialcyclehasbeenshowntobeoperativein several language families. Here it is shown that it also operates within a single language. It happens that the existential fī that has been adduced as an example of a type A in the Arabic of Damascus, Syria, negated with the standard spoken Arabic verbal negator mā, does not participate in a negative cycle, but another Arabic existential particle does. Reflexes of the existential particle šay(y)/šē/šī/ši of southern peninsular Arabic dialects enter into a type A > B configuration as a univerbation between mā and the existential particle ši in reflexes of maši. It also enters that configuration in others as a uni- verbation between mā, the 3rd-person pronouns hū or hī, and the existential particle šī in reflexes of mahūš/mahīš.Atthatpoint,theexistentialparticlešī loses its identity as such to be reanalyzed as a negator, with reflexes of mahūš/mahīš negating all manner of non-verbal predications except existen- tials. As such, negators formed of reflexes of šī skip a stage B, but they re- enter the cycle at stage B > C, when reflexes of mahūš/mahīš begin negating some verbs. The consecutive C stage is encountered only in northern Egyptian and southern Yemeni dialects. An inchoate stage C > A appears only in dialects of Lower Egypt. Keywords: Arabic dialects, grammaticalization in Arabic, linguistic cycles, standard negation, negative existential cycle, southern Arabian peninsular dialects 1 Introduction The negative existential cycle as outlined by Croft (1991) is a six-stage cycle whereby the negators of existential predications – those positing the existence of something with assertions analogous to the English ‘there is/are’–overtake the role of verbal negators, eventually replacing them, if the cycle continues to *Corresponding author: David Wilmsen, Department of Arabic and Translation Studies, American University of Sharjah P.O. -

Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College M.Ed. In TESL Program Language Group Specific Informational Reports Produced by Graduate Students in the M.Ed. In TESL Program In the Feinstein School of Education and Human Development Language Group: Arabic Author: Joy Thomas Program Contact Person: Nancy Cloud ([email protected]) http://cache.daylife.com/imagese http://cedarlounge.files.wordpress.com rve/0fxtg1u3mF0zB/340x.jpg /2007/12/3e55be108b958-64-1.jpg Joy http://photos.igougo.com/image Thomas s/p183870-Egypt-Souk.jpg http://www.famous-people.info/pictures/muhammad.jpg Arabic http://blog.ivanj.com/wp- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Learning_Arabi content/uploads/2008/04/dubai-people.jpg http://www.mrdowling.com/images/607arab.jpg c_calligraphy.jpg History • Arabic is either an official language or is spoken by a major portion of the population in the following countries: Algeria, Bahrain, Chad, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen • Arabic is a Semitic language, it has been around since the 4th century AD • Three different kinds of Arabic: Classical or “Qur’anical” Arabic, Formal or Modern Standard Arabic and Spoken or Colloquial Arabic • Classical Arabic only found in the Qur’an, it is not used in communication, but all Muslims are familiar to some extent with it, regardless of nationality • Arabic is diglosic in nature, as there is a major difference between Modern Standard and Colloquial Arabic • Modern -

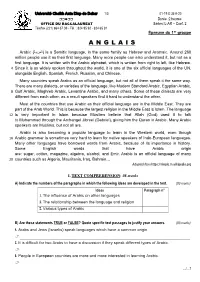

A N G L a I S Is a Semitic Language, in the Same Family As Hebrew and Aramaic

Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar 1/3 01-19 G 35 A-20 Durée :2 heures OFFICE DU BACCALAUREAT Séries: L-AR – Coef. 2 Téléfax (221) 864 67 39 - Tél. : 824 95 92 - 824 65 81 Épreuve du 1er groupe A N G L A I S is a Semitic language, in the same family as Hebrew and Aramaic. Around 260 (العربية) Arabic million people use it as their first language. Many more people can also understand it, but not as a first language. It is written with the Arabic alphabet, which is written from right to left, like Hebrew. 4 Since it is so widely spoken throughout the world, it is one of the six official languages of the UN, alongside English, Spanish, French, Russian, and Chinese. Many countries speak Arabic as an official language, but not all of them speak it the same way. There are many dialects, or varieties of the language, like Modern Standard Arabic, Egyptian Arabic, 8 Gulf Arabic, Maghreb Arabic, Levantine Arabic, and many others. Some of these dialects are very different from each other; as a result speakers find it hard to understand the other. Most of the countries that use Arabic as their official language are in the Middle East. They are part of the Arab World. This is because the largest religion in the Middle East is Islam. The language 12 is very important in Islam because Muslims believe that Allah (God) used it to talk to Muhammad through the Archangel Jibreel (Gabriel), giving him the Quran in Arabic. Many Arabic speakers are Muslims, but not all are.