The First Century of the Churchman 1 JOHN WOLFFE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evangelicalism and the Church of England in the Twentieth Century

STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY Volume 31 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 1 25/07/2014 10:00 STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY ISSN: 1464-6625 General editors Stephen Taylor – Durham University Arthur Burns – King’s College London Kenneth Fincham – University of Kent This series aims to differentiate ‘religious history’ from the narrow confines of church history, investigating not only the social and cultural history of reli- gion, but also theological, political and institutional themes, while remaining sensitive to the wider historical context; it thus advances an understanding of the importance of religion for the history of modern Britain, covering all periods of British history since the Reformation. Previously published volumes in this series are listed at the back of this volume. Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 2 25/07/2014 10:00 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL EDITED BY ANDREW ATHERSTONE AND JOHN MAIDEN THE BOYDELL PRESS Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 3 25/07/2014 10:00 © Contributors 2014 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2014 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 978-1-84383-911-8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. -

The First Century of the Churchman 1 JOHN WOLFFE

The First Century of The Churchman 1 JOHN WOLFFE In October 1879 The Churchman, which claimed to be 'commenced out of a single desire to promote the glory of God', first appeared. 2 Although there have been significant changes in the character of the periodical during its history it has now maintained unbroken publication for over a century, as a monthly until 1920 and as a quarterly thereafter. This achievement is not only intrinsically worthy of a commemorative article, but indicates that The Churchman is an important and largely untapped source for the history of Evangelicalism within the Church of England during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries? This article thus aims to provide a brief account of the magazine's own development and to relate this to the wider context of the position of Anglican Evangelicalism in the Church and nation. The discernment of historical turning points is always a hazardous undertaking, but when the attempt is made, it can be concluded that the late 1870s were marked by more significant changes than other more instantly remembered phases in British history. When The Churchman began publication Disraeli's Conservative Government had been in office for nearly six years, but within six months it had suffered a crushing General Election defeat and Disraeli's own death a year after this removed one of the giants of the mid-Victorian political scene. In the month after The Churchman's first appearance Gladstone initiated his famous Midlothian campaign, presenting to the electorate a classic indictment of allegedly imperialist foreign policies. In economic and social life, too, 1879 was a noteworthy year. -

Bradford Cathedral Annual Report 2019

Bradford Cathedral Annual Report 2019 1 2 Contents Introduction 05 Statement from the Bishop of Leeds 08 Cathedral Staff & Officers 09 A Statistical Snapshot of 2019 09 Agenda for Annual Vestry Meeting 10 Agenda for APCM 10 Minutes of the Annual Parochial Church (APCM) Meeting 11 Minutes of the Public Annual Vestry Meeting 13 Architect’s Report 14 Artspace 15 Bell Ringing 16 Carers’ Crafts 16 Children’s Space 16 Comms, Marketing and Events 17 Community Committee 20 Eco Group 22 Education 22 Faith Trail 26 Flowers 27 The Friends of Bradford Cathedral 28 House Group 29 Inner Bradford Deanery Synod 29 Income Development 30 Just A Minute Group 31 Monday Fellowship 31 Music and Choir 32 Prayer Ministry 34 Safeguarding 35 Silence Clinic 35 Silence Space 36 Toddlers Group 36 Vergers’ Report 37 Visitors 37 Worship 40 Finance 41 Thank you to Jill Wright for proof-reading this document. 3 4 ‘We are here to enrich the lives of others.’ Introduction That was a key line in the opening paragraph During 2019 there were more staff to my 2018 Annual Report. The Very Revd changes. We said good-bye to: Jerry Lepine, In 2019, our Centenary year as a cathedral, Ed Jones Associate Organist Dean of Bradford we certainly achieved that. From the launch on the first Sunday in January to the Charlie Murray Heritage Research & glorious Centenary Service on Sunday 24th Outreach Officer November, we made 2019 a very special year. and Choral Scholar You can see some of the memories in the Ann Foster Music Department margins of this report. -

Pages 6-7 Archdeacon's View

April 2014 NEED TO KNOW I STORIES I AREA UPDATES I EVENTS NEAR YOU Archdeacon’s View By Robin King, Archdeacon of Centenary Stansted A FEW years ago Katharine, my wife, and challenges I found ourselves venturing into the Sahara desert (it’s a for schools www.chelmsford.anglican.org long story). It is a truly beautiful place, and we were just tourists, but imagine what we would have done if, during our brief exploration, we’d come across someone staggering over the dunes, sun-burnt and blistered, starving and badly dehydrated. Any one of us, finding ourselves in that situation, would have rushed up and offered food, water, shade and a soothing lotion for his wounds – we would have done everything in our power to ease any suffering. The trouble is, in doing so, it’s possible that we might have been interfering in something very holy. Two thousand years ago, in a different desert, the sun-burnt and blistered man might have been Jesus – who wasn’t staggering around there because he was lost, but because, “the Spirit sent him out into the desert.” Education special (Mark 1:12-13) to mark 100th Jesus went into the wilderness in order to prepare himself for the incredible anniversary of ministry he was about to undertake. That’s CONTINUED ON PAGE 5 diocese: Pages 6-7 God Movie Project Two Rivers Mission gets green light to plans two weeks of expand and recruit events in Colne more participants and Stour valleys Page 4 NB Page 1 -- ■ Look inside for the annual report to parishes ■ Wishing all our readers a happy Easter 2 THE MONTH April 2014 THE month — Synod encourages new ways of sharing the good news of Christ 'Fresh Expressions should be business as usual' FRESH EXPRESSIONS of church should ministry following a debate introduced be “business as usual” the Bishop of by David Hawkins, the Bishop of Chelmsford, Stephen Cottrell has said. -

First Name Last Name Country Jeffrey Honey CA Joseph

First_Name Last_Name Country Jeffrey Honey CA Joseph Maceyovski CA Marianne Steenken DE Rachel Wolf US Kent Minault US Tom Walsh US David Rangel US John Morrison US Frances Goff US Douglas Estes US Robert Gore US David Ellringer US Ronald Gelden US Clifford Johnson US Kathleen Maher US Simone Morgen US Patrick De La Garza Und Senkel US Deborah Richmond CA Bertha Kriegler US Linda Owen US Vincent De Stefano US Gordon Edwards AU Debra Rehn US Rik Reynolds US David Greene US mathew thomas AU chris Helcermanas-Benge CA john papandrea US Warren Kazor CA glenn kitashima US Eric Stordahl US Cynthia Curtis US Meryle A. Korn US DBellUS Ovina Feldman US Nancy Wrensch US Michael Dennis US Frank Heacock US Kathy Spera US Ryan Moore US Hartson Doak US Kerry Weaver US Larry Blount US Thomas Windberg US susan peirce US Ian Carman US Mark Jacobs US Karen Bowden US Lisa Butterfield US Becky Daiss US Tom Winstead US Joe Ferriter US Lori Mulvey US Anita Chariw US Donald Cronin US Ernest Montoro US RICHARD CURRY US Stephen and Robin Newberg US Michael David Sasson US James Milnthorpe US Ann Thryft US Allie Robbins US Terrie Williams US Michael Tomczyszyn US Mark Gallegos US John Hendricks US John Keiser US Ron Blankenship US Susan Osada US Jim Steitz US Ron Schutte US John Bernard US JOSEPH LITE US Guy Zahller US Jim Newton US Liam Black CA William Lee Kohler US Allan Campbell US Mark Cappetta US Cornelius Coughlin US Dee Randolph US Anthony Trupiano US Glenn Martin US Robert Justice US Ken Kolbe US Joseph Kelley US dale riehart US Jeffrey Hearn US Shawn Dufraine US Brent Rocks US CHARLES HANCOCK US John Holmes US Terrence Parkhurst US Douglas Buckley US Sister Carol Boschert US Michael Landers US Frank Hyden US Randall Paske US Janice Foss US Wojciech Rowinski US Robert Ziegler US David Dresser US Donna Bonetti US Bob Thomas US Robert Angone US Patty Bonney US Joe Rogers US Kathryn Rose US John Bill US Vincent O'Neill US William Hulme US Leonard Tremmel US Janet Martin CA Callie Riley US Galloway Allbright US Michael Klausing US Christine Roane US Gary Grice US The Rev. -

6Th March 1969

hot line THE AUSTRALIAN CHURCH THE AUSTRALIAN A round-up of church Press comment at home and abroad. Among Victorians mentioned in the All Souls', Leichhardt (Sydney) since RECORD New Year honours list was Mrs Kathleen 1965, has been appointed curate in LAN A HUN CHURCHMAN mania's Church News takes the Bright•Park9r, noted worker for the charge of St. John's. Mona Vale. tells of a trust fund which is would-be Cranmers to task who G.F.S. and A.B.M. who was awarded Rev. Harold Hinton has been ap- The paper for Church of the O.B.E. for services to the church pointed curate of All Saints', Nowra England people — Catholic, being set up in Winnipeg by ignore the rubric requiring a and community. (Sydney), with oversight of Kangaroo dissident Anglicans who wish to sermon at Holy Communion. He The Archbishop of Melbourne ordain- Valley. Apostolic, Protestant and CHURCH RECORD ed the following in St. Paul's Cathedral Mr Warwick Olsen has been appoint- Reformed. THE remain out of the proposed mer- quotes St. Bernadino of Siena on February 9: ed Director of Church Information and CHURCH OF ENGLAND NEWSPAPER —EIGHTY-NINTH YEAR OF PUBLICATION (Priests) Revs. Gerald E. Beaumont Mr Leslie Mien has been appointed Subscription $3 per, year, ger with the United Church. who said: "There is less peril for (St. Andrew's, Brighton), David T. C. This will enable them to have Bout (St. Mark's, Camberwell), Stewart Church Information Officer (Sydney). Mr posted. Editorial and Busi- Registered at the G.P.O., Sydney, for transmission by post Printed by John Fairfax and your soul in not hearing Mass Jillett has been Book 'Review Editor of immediate resources when the F. -

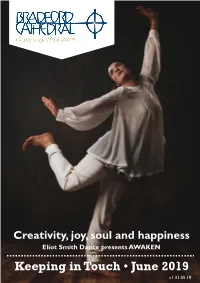

Keeping in Touch • June 2019

Creativity, joy, soul and happiness Eliot Smith Dance presents AWAKEN KeepingKeeping in Touch in Touch • June 2019 1 v1 31.05.19 2 Keeping in Touch Keeping in Touch Contents Bradford Cathedral 1 Stott Hill, Canon Mandy: A time to celebrate 04 Bradford, Thy Kingdom Come 06 West Yorkshire, Mission 10 BD1 4EH Centenary Prayer 12 (01274) 77 77 20 Cathedral Centenary Festival 13 [email protected] Unity with Diversity 19 Bradford Cathedral Choir Festival 21 News in Brief 24 Find us online: Diocesan link with Sudan 26 bradfordcathedral.org/ A Quick Q&A with Andy McCarthy 29 StPeterBradford Photo Gallery 30 @BfdCathedral Volunteers Week 34 Approaching an uncertain future 35 @BfdCathedral Refugee Week 2019 36 mixcloud.com/ Eliot Smith Dance perform AWAKEN 41 BfdCathedral What’s On 49 bradfordcathedral. Music List 53 eventbrite.com Who’s Who 57 Everyone loves a chocolate Front page photo: fountain: the choir visit Germany Eliot Smith Dance Please submit content for the next edition to commsandevents @bradfordcathedral.org before 21st June 2019 Keeping in Touch 3 Welcome A time to celebrate The saying, “Dwarfs standing on the the long hoped for extension work shoulders of giants” is believed to be for the Cathedral was realized, a first coined by Bernard of Chartres in visionary plan which had waited 1159. It was then later popularized by nearly forty years. When we asked Isaac Newton in 1675. It was used as how, after so long, Provost Tiarks a metaphor to explain that we see had succeeded in raising the money farther than our predecessors; not for the Cathedral expansion work, because our vision is better, but the answer surprised us. -

The Cathedral Church of St Peter, Bradford Monuments & Memorial Inscriptions Within the Building, Summer 2015

The Cathedral Church of St Peter, Bradford Monuments & Memorial Inscriptions within the building, summer 2015 Transcriptions and Download created by members of Bradford Family History Society Images by courtesy of Cathedral staff. The Cathedral Church of St Peter, Bradford Monuments & Memorial Inscriptions within the building About this church The Parish There has been a church on the site now occupied by the Cathedral for Bradford was an Ancient Parish which existed before parish registers about 1000 years. The first building was probably a small wooden one started. It covered a wide area, taking in the thirteen townships of to be replaced by a stone one sometime around 1200. It has undergone Allerton, Bowling, Bradford, Clayton, Eccleshill, Haworth (which many changes since then. Scots raiders burnt its roof in the 14th century, included Oxenhope and Stanbury), Heaton, Horton, Manningham, in 1643 it was the centre of fighting between Royalist and Roundhead North Bierley (which included Low Moor and Wibsey), Shipley, armies, with the Tower protected by bags of wool. There were Thornton (which included Denholme) and Wilsden. Chapels of Ease significant alterations in the 1890’s and again, after the Parish Church were established at Haworth in the fifteenth century, at Thornton and of St Peter became Bradford Cathedral. Wibsey in the early sixteenth century, and at Great Horton in 1806; there was also a private chapel built at Bierley in 1766. From the early For a detailed history of the church, see the Cathedral’s own nineteenth century onwards many churches were built and new website: www.bradfordcathedral.org/ ecclesiastical parishes created. -

Bishop Walter Baddeley, 1894-1960: Soldier, Priest and Missionary

Bishop Walter Baddeley, 1894-1960: Soldier, Priest and Missionary. Antony Hodgson Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy King’s College, London. Downloaded from Anglicanhistory.org Acknowledgements I am most grateful to the staff and trustees of several libraries and archives especially; Blackburn Diocesan Registry, Blackburn Public Library, the Bodleian Library, the Borthwick Institute, York, the National Archives, King’s College, London, Lambeth Palace Library, Lancashire County Records Office, the Harris Library, Preston, St Deiniol’s Library, Hawarden, St Annes-on-the-Sea Public Library, the School of Oriental and African Studies, Teeside Public Records Office and York Minster Library. I wish to acknowledge the generous assistance of the Clever Trustees, the Lady Peel Trustees and Dr Richard Burridge, dean of King’s College, London. Colleagues and friends have given much help and I would particularly like to thank David Ashforth, John Booth, Colin Podmore, John Darch, Dominic Erdozain, Christine Ellis, Kenneth Gibbons, William Gulliford, Peter Heald, William Jacob, Bryan Lamb, Geoffrey Moore, Jeremy Morris, Paul Wright and Tom Westall. Finally, I owe the greatest debt of gratitude to my wife, Elizabeth and my supervisor, Professor Arthur Burns. ii Synopsis of Thesis The dissertation consists of an introduction and five biographical chapters, which follow Baddeley’s career from subaltern in 1914 to diocesan bishop in 1954. The chapters correspond with four distinct periods in Baddeley’s life: the First World War 1914-19 (Chapter 1), Melanesia, 1932-47 (Chapter 2), the suffragan bishopric of Whitby, 1947-54 (Chapter 3), and the diocesan bishopric of Blackburn 1954-60 (Chapters 4 and 5). -

Cathedrals and Change in the Twentieth Century

Cathedrals and Change in the Twentieth Century: Aspects of the life of the cathedrals of the Church of England with special reference to the Cathedral Commissions of 1925; 1958; 1992 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2011 Garth Turner School of Arts, Histories and Cultures Contents Abstract 3 Declaration 4 Copyright statement 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 5 Part I The Constitutional development of the cathedrals Introduction: 7 The commissions’ definitions of ‘cathedral’ 8 The membership of the Commissions 9 Chapter I The Commission of 1925 and the Measure of 1931 12 Nineteenth Century Background 12 Discussion of cathedrals in the early twentieth century 13 The Commission of 1925 19 The Commission’s working methods 20 The Commission’s recommendations 20 The implementation of the proposals 24 Assessment 28 Chapter II The Commission of 1958 and the Measure of 1963 30 The Commission: membership 30 The Commission at work 30 Cathedrals in Modern Life 36 The Report in the Church Assembly 40 Assessment 49 Chapter III The commission of 1992 and the Measure of 1999 51 Cathedrals in travail 51 The complaints of three deans 59 The wider context 62 Moves toward reform 62 Setting up a commission 64 The working of the Commission 65 The findings of the sub-commissions 65 The bishops 65 The chapters 67 The laity 69 The report 70 The report in the Synod 76 An Interim Measure 88 A changed Anglican mentality 92 Part II Aspects of the life of the cathedrals Introduction 97 Chapter IV A Preliminary -

St Paul's Day Preachers from 1954 St Paul's Covent Garden St Stephen

St Paul’s Day Preachers from 1954 St Paul’s Covent Garden 1954 The Reverend James Adams The Honorary Chaplain St Stephen Walbrook 1955 The Reverend Chad Varah Rector of St Stephen Walbrook 1956 The Honorary Chaplain 1957 The Honorary Chaplain 1958 The Venerable Wallis Thomas Archdeacon of Merioneth 1959 The Right Reverend Robert Mortimer Bishop of Exeter St Mary Abchurch 1960 The Reverend Canon Michael Stancliffe Rector of St Margaret's Westminster 1961 The Very Reverend Eric Abbott Dean of Westminster 1962 The Right Reverend. Mervyn Stockwood Bishop of Southwark 1963 The Honorary Chaplain 1964 The Reverend J W M Vyse Rector of St Mary Abchurch 1965 The Right Reverend Victor Pyke Bishop of Sherborne 1966 Tue 25th January The Right Reverend John Tiarks Bishop of Chelmsford 1967 The right Reverend R.W. Standard Dean of Rochester 1968 Thu 25th January The Right Reverend John Philips Bishop of Portsmouth 1969 The Reverend Kenneth Slack Minister of the City Temple 1970 Mon 26th January The very Reverend Martin Sullivan Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral 1971 Mon 25th January The Right Reverend David Say Bishop of Rochester 1972 Tue 25th January The Right Reverend Geoffrey Tiarks Bishop of Maidstone 1973 Thu 25th January The Most Reverend G O Williams Archdeacon of Bedford 1974 Fri 25th January The Right Reverend John Trillo Bishop of Chelmsford 1975 The Venerable James Adams The Honorary Chaplain 1976 The Reverend John Kirkham Domestic Chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury 1977 Tue 25th January The Right Reverend Philip Goodrich MA Bishop of Tonbridge -

The Hatch Herald

THE HATCH HERALD April 2013 The Monthly Magazine for Members and Friends of St. Anne’s Church Larkshall Road Chingford (CHURCH OF ENGLAND) No. 230 www.stannee4.org.uk 50p SERVICES AT ST ANNE’S DATE TIME SERVICE Sunday 31st March 10:00 Parish Eucharist - Easter Day Friday 5th April 10:00 Communion Sunday 7th April 10:00 Parish Eucharist Friday 12th April 10:00 Communion Sunday 14th April 10:00 Parish Eucharist 11.45 Parish A.G.M. Friday 19th April 10:00 Communion Sunday 21st April 10:00 Informal Eucharist Friday 26th April 10:00 Communion Sunday 28th April 10:00 Parish Eucharist 12:30 Simple Lunch 17:30 Informal Service FORTHCOMING EVENTS April Diary Tuesday 2nd Saturday 4th May 8pm M.L.T. meeting St. Anne’s 60th Anniversary Celebrations, service of thanksgiving followed by a 3 Saturday 6th course diner—Tickets £20 from Lindsey or 10am Mini Market in aid of Mildmay Joanne. Mission Monday 8th Saturday 13th & Sunday 14th July 8pm Plant Committee Arts and Crafts weekend Sunday 14th 11.45 am Parish A.G.M. Regular Church Events Annie's Angels—Tuesdays during term time 1.30 –2.30pm in church Healing centre—2-4pm during term time in the Vestry (see Eira Endlesbury) Study Prayer Lunch –Alternate Wednesdays 12-2.00pm in the Vestry (see Jenny Howland) 2 thanksgiving followed by a dinner – tickets £20. Please come and celebrate with us. Later on in July we are holding a ‘festival of Easter creativity’, but more of that in the next Greetings issue of the Hatch Herald.