Freedom, Flags, and "Never Forgetting": Commemorative Practices and Responses in the Ten Years After September 11 Juliana Halpert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journeys of the Beat Generation

My Witness Is the Empty Sky: Journeys of the Beat Generation Christelle Davis MA Writing (by thesis) 2006 Certificate of Authorship/Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all the information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Candidate 11 Acknowledgements A big thank you to Tony Mitchell for reading everything and coping with my disorganised and rushed state. I'm very appreciative of the Kerouac Conference in Lowell for letting me attend and providing such a unique forum. Thank you to Buster Burk, Gerald Nicosia and the many other Beat scholars who provided some very entertaining e mails and opinions. A big slobbering kiss to all my beautiful friends for letting me crash on couches all over the world and always ringing, e mailing or visiting just when I'm about to explode. Thanks Andre for making me buy that first copy of On the Road. Thank you Tim for the cups of tea and hugs. I'm very grateful to Mum and Dad for trying to make everything as easy as possible. And words or poems are not enough for my brother Simon for those silly months in Italy and turning up at that conference, even if you didn't bother to wear shoes. -

February 2021

Monmouth Viewfinder SEEING THE WORLD THROUGH MANY EYES The Monthly Publication of Monmouth Camera Club | February 2021 Join Us on Zoom FEBRUARY 11 at 7:30 pm Creative architecture w/ Claire gentile DETAILS AND ZOOM LINK TO BE SENT VIA EMAIL Sparring Bison by Colette Cannataro MONMOUTH CAMERA CLUB February 2021 Club Information THE MONMOUTH CAMERA CLUB provides a forum and gathering place for amateur and professional photographers at all levels of accomplishment. It allows members to share MCC is a proud member their experiences, to increase their knowledge, to find new of NJFCC + PSA stimulation for photographic endeavors, and to make new friends. Our club was founded in 1979 and meets twice per month, on Thursday evenings, from September to June. Lectures and Information / Updates discussions span a wide array of topics. Most speakers are accomplished photographers. available online & social media: Competitions are held for digital and printed images and provide constructive critiques from an objective judge. www.mcc-nj.org For more information, visit www.mcc-nj.org. www.instagram.com/Monmouth_Camera_Club MEETINGS Colts Neck Reformed Church (Red-brick building behind church) 139 Route 537, Colts Neck, NJ www.meetup.com/monmouth-camera-club/ MEMBER -Photographic Society of America -NJ Federation of Camera Clubs www.facebook.com/monmouthcameraclub mcc-nj.org Page 2 MONMOUTH CAMERA CLUB February 2021 Upcoming MCC Events Take Note: Given current conditions and with the health & safety of our members as our highest priority, it is expected that we will not be holding indoor physical presence meetings for the foreseeable future. We will continue to communicate all updates with our members. -

Nostalgia and the Irish Fairy Landscape

The land of heart’s desire: Nostalgia and the Irish fairy landscape Hannah Claire Irwin BA (Media and Cultural Studies), B. Media (Hons 1) Macquarie University This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media and Cultural Studies. Faculty of Arts, Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies, Macquarie University, Sydney August 2017 2 Table of Contents Figures Index 6 Abstract 7 Author Declaration 8 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction: Out of this dull world 1.1 Introduction 11 1.2 The research problem and current research 12 1.3 The current field 13 1.4 Objective and methodology 14 1.5 Defining major terms 15 1.6 Structure of research 17 Chapter One - Literature Review: Hungry thirsty roots 2.1 Introduction 20 2.2 Early collections (pre-1880) 21 2.3 The Irish Literary Revival (1880-1920) 24 2.4 Movement from ethnography to analysis (1920-1990) 31 2.5 The ‘new fairylore’ (post-1990) 33 2.6 Conclusion 37 Chapter Two - Theory: In a place apart 3.1 Introduction 38 3.2 Nostalgia 39 3.3 The Irish fairy landscape 43 3 3.4 Space and place 49 3.5 Power 54 3.6 Conclusion 58 Chapter Three - Nationalism: Green jacket, red cap 4.1 Introduction 59 4.2 Nationalism and the power of place 60 4.3 The wearing of the green: Evoking nostalgia for Éire 63 4.4 The National Leprechaun Museum 67 4.5 The Last Leprechauns of Ireland 74 4.6 Critique 81 4.7 Conclusion 89 Chapter Four - Heritage: Up the airy mountain 5.1 Introduction 93 5.2 Heritage and the conservation of place 94 5.3 Discovering Ireland the ‘timeless’: Heritage -

Download Survey Written Responses

Family Members What place or memorial have you seen that you like? What did you like about it? 9/11 memorial It was inclusive, and very calming. 9/11 Memorial It was beautiful. Park with a wall with names on it. Angels status. Water fountain. Water fountain area and location. Touchscreen info individual memorials Oklahoma City Memorial memorabilia collections 9-11 memorial Place to reflect and remember; reminder of the lessons we should Several Washington DC memorials learn from hateful acts Love that all the names were 911 New York City Place on a water fall Before the 911 Memorial was erected; I visited the site a month after the event. I liked its raw state; film posters adverts still hanging up from films premiered months prior. The brutal reality of the site in baring its bones. The paper cranes left by the schoolchildren. The Holocaust Museum along with the Anne Frank Haus spoke to me; the stories behind the lives of these beautiful people subjected to nothing but hate for who they loved and who they were. The educational component to the Holocaust Museum in D.C. spoke volumes to me. To follow the journey of a Holocaust victim... For Pulse, I see a blend of all of this. To learn the stories of why so many sought refuge and enjoyment there. Why did so many leave their "families"? Because they could not be who they were. I find it is important that we teach this lesson-it's okay to be who you are-we have your back-we love you-we will dance with you-in any form of structure. -

Karels2018 Redaction.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Performing Remembrances of 9/11 Martina Karels PhD The University of Edinburgh 2017 Declaration This is to declare that the work contained within has been composed by me and is entirely my own work. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Martina Karels Edinburgh, 30 June 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... i LAY SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. -

Songs of Loss: Springsteen and 9/11 the Basics Time Required 1-2

Songs of Loss: Springsteen and 9/11 The Basics Time Required 1-2 class periods Subject Areas Middle School Humanities Contemporary America, 1968-present Common Core Standards Addressed: Writing Standards K-5 Author Terra Bialy (2004) The Lesson Introduction Bruce Springsteen (b. 1949) wrote the songs “You’re Missing” and “Empty Sky” for his CD titled The Rising (Columbia, 2002) as a response to the events of September 11, 2001. Springsteen’s home county of Monmouth in New Jersey lost 158 people on 9/11. Within days of the towers collapsing, Springsteen began writing songs. These two songs were inspired by discussions that he had with two New Jersey widows who lost their husbands when the twin towers of the World Trade Center collapsed. Guiding Questions What do you know about the 9/11 terrorist attacks? Learning Objectives Students will present responses to and interpretations of literature, making reference to the literary elements found in the text and connections with their personal knowledge and experience produce interpretations of literary works that identify different levels of meaning and comment on their significance and effect write stories, poems, literary essays, and plays that observe the conventions of the genre and contain interesting and effective language and voice. Preparation Instructions Songs used in lesson: • “You’re Missing” Bruce Springsteen • “Empty Sky” Bruce Springsteen Lesson Activities Introductory learning activities: • Begin by reading the monologue “A Very Intriguing Train,” page 127 from With Their Eyes. • When you finish the reading ask students to write a response to the question “What do you remember about the events of September 11, 2001?” Students should then share their responses with a partner. -

The Politico-Aesthetics of Groundlessness and Philippe Petit’S High-Wire Walk

ARTICLES The Politico-Aesthetics of Groundlessness and Philippe Petit’s High-Wire Walk Gwyneth Shanks When I see two oranges, I juggle; when I see two towers, I walk. —Philippe Petit, To Reach the Clouds A figure stands in open air. Centred in the photo, the body seems suspended in the expanse of hazy, blue sky that opens up around their small form. On the right-hand side of the image, one tower of the newly built World Trade Center (WTC) looms. The figure is small in comparison, a smudge of black made insubstantial next to the clean, geometric grid of the tower’s detailed façade. And yet it is the figure that arrests the viewer’s gaze. The ground upon which this person stands is nothing but a thin cable, barely visible in the photograph. The photo, taken the morning of August 7, 1974, is of French high-wire walker Philippe Petit. Captured by Petit’s friend and co-conspirator, Jean-Louis Blondeau, the image reveals a figure caught between ground and sky, between the two towers of the WTC, and between life and death. Suspended between the Twin Towers, balanced on his wire, Petit’s walk celebrates the precarity of groundlessness. Philippe Petit on a cable suspended between the two towers of the newly completed World Trade Center in New York City, August 7, 1974. Film still from the 2008 documentary, Man on Wire, directed by James Marsh. Photo: Jean-Louis Blondeau, 1974. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Gwyneth Shanks is the Interdisiplinary Art Fellow at the Walker Art Center. She holds a PhD in Theater and Performance Studies from University of California, Los Angeles and an MA in Performance Studies from New York University. -

This Bridge Called My Back Writings by Radical Women of Color £‘2002 Chenic- L

This Bridge Called My Back writings by radical women of color £‘2002 Chenic- L. Moiaga and Gloria E. Anzaldua. All rights reserved. Expanded and Re vised Third Edition, First Pr nLing 2002 First Edition {'.'1981 Cherrie L. Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldua Second Edition C 1983 Cherne L. Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldua All rights reserved under International an d Pan American Copyright Conventions. Published by Third Woman Press. Manufactured in the United Stales o( America. Printed and b ound by M c Na ugh ton & Gunn, Saline, Ml No p art of this book may be reproduced by any me chani cal photographic, or electronic process, or in the form of a phonographic recording nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or otherwise copied, for public or private use, without tne prior written permission of the publisher. Address inquiries to: Third Woman Press. Rights and Permissions, 1329 9th Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 or www.thirdwomanpress.com Cover art: Ana Mendieta, Body Tracks (1974), perfomied bv the artist, blood on white fabric, University of Iowa. Courtesy of the Estate of Ana Mendieta and Galerie Lelong, NYC. Cover design: Robert Barkaloff, Coatli Design, www.coatli.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data This b ridge called my back : writ ines by radical women of color / edi tors, Cherne L. Moraga, Gloria E. AnzaTdua; foreword, Toni Cade Bambara. rev an d expanded 3rd ed. p.cm. (Women of Color Series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-943219-22-1 (alk. paper) I. Feminism-Literary collections. 2. Women-United States-Literary collections. -

9/11 and Performing Regenerative Violence A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Empty Sky: 9/11 and Performing Regenerative Violence A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama and Theatre by Raimondo Genna Committee in charge: Professor Emily Roxworthy, Chair Professor Patrick Anderson Professor Anthony Kubiak Professor Manuel Rotenberg Professor John Rouse Professor Janet Smarr 2010 Copyright Raimondo Genna, 2010 All rights reserve The Dissertation of Raimondo Genna is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego University of California, Irvine 2010 iii DEDICATION To my mother, Maria, Danny, Peter, Juan, and Jewel. You have been my light in the dark. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ........................................................................................................... iii Dedication .................................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents ....................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... vi Vita ............................................................................................................................. vii Abstract ...................................................................................................................... -

Trip Book 2019-2020 Vol 3

2019-2020 SCUCS TRIPS VOL. 3 www.communitytourstravel.com ALL TRIPS LEAVE FROM SCUCS, INC. 537 W. NICHOLSON ROAD AUDUBON, NJ 08106 Check out our new trips website at: www.communitytourstravel.com (856) 456-1121 press 2 TRIP INSURANCE IS AVAILABLE! SCUCS 2019-2020 TRIP BROCHURE GENERAL INFORMATION Office - The office is open Monday through Friday from Cancellation - Trips cannot be booked or cancelled by 9:00 am to 4:00 pm. The telephone number is (856) 456- leaving a phone message or sending an email. SCUCS 1121. Press 2 for the Trips Department. If all the lines has the right to cancel reservations if a deposit is not to our department are busy, you will be able to leave received within one week of making your reservation a message and we will call you back. Meal choices and the right to cancel any tour if there is an insufficient should be called in after 4:00 and left on the answer- response. If a trip is cancelled due to insufficient re- ing machine. sponse, you will receive a full refund without any deduc- There is no residency requirement for any of our trips. tions. Passengers canceling less than four (4) weeks There is no age requirement to participate. The trips are before the scheduled day trip will not be refunded mainly geared to senior citizens; however, some trips unless insurance has been taken out on the trip. In do require a lot of walking. If this is a problem for you, some cases, just a Cancellation Fee may apply. -

911-0911.Pdf

VOLUME 1: BEYOND GROUND ZERO, SEPTEMBER 2011 I can’t believe it is 10 years since September 11, 2001. It really seems almost like a movie—a terrible movie. here’s nothing more pow- were there. The ripple effect of to participate in it. But after 10 erful and compelling than the pain inflicted that terrible day years, several say they may finally Thearing the facts about continues to affect and hurt many be ready for it. It should be made an incident directly from a first- families, friends and loved ones. available to them. person source. We have done We found that many marriages We found that counseling has that in the development of the and relationships dissolved or been offered to the children of four-volume historic report, Out ended in unfortunate divorces responders, but in many instanc- of the Darkness, presented here. after 9/11 because some indi- es, it hasn’t been offered to their To do so, we spent time with key viduals couldn’t understand or spouses and significant others personnel in each involved city accept the commitment, respon- who have been left to deal with to discuss the events of Sept. 11, sibilities or emotional baggage the ramifications on their own. 2001, and the aftermath of that being carried by the responder They need help too. unforgettable day. they loved. Those who were hired after We chose the title because so Yet, the people we spoke with 9/11 must be sensitive to those many of those we spoke to report- carry on with their lives. -

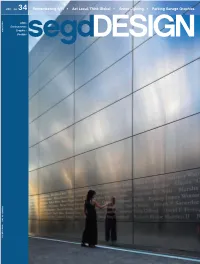

Remembering 9/11 Act Local, Think Global Green Lighting Parking

2011 no. 34 Remembering 9/11 n Act Local, Think Global n Green Lighting n Parking Garage Graphics segdDESIGN segdDESIGN Signs Environments Graphics Designs EXHIBITS | EVENTS | ENVIRONMENTS NUMBER 34, 2011 www.segd.org 3801 Vulcan Drive Nashville, TN 37211 www.1220.com (800) 245·1220 G22274_cover.indd 2 11/28/11 5:13 PM The terrorist attacks of Septem- ber 11, 2001 endure as indelible visions of chaos, destruction, REMEMBERING and unimaginable loss. About 2 billion people—one-third of the world’s population—watched the day’s tragedies as they un- folded live on television and online. While the world watched in the days and weeks afterward, two architects in New York City began to draw. / “It was my way of getting it out, 9Two architects, two visions, and two11 memorials commemorate what was seared in my memory,” loss and foster healing. By LesLie WoLke says Frederic Schwartz, princi- pal of Frederic Schwartz Archi- tects and longtime SoHo resident. He began by drawing the collapsing towers and over time, “I started to redraw the skyline. I started to draw what should happen,” he says. A couple of miles away in his home on the Lower East Side, Michael Arad, two years out of architecture school and employed at the New York City Housing Authority, began to sketch “a pair of twin voids tearing open the surface of the Hudson River. This inexpli- cable, enigmatic image seemed to capture a sense of rupture, loss, and persistent absence and stayed in my imagination.” A decade of consequences and contemplation have passed and those early drawings by Schwartz and Arad have transformed from paper musings into the two most profound memorials to the victims of September 11th: Arad’s National September 11 Memorial at the World Trade Center and, across the Hudson River, Schwartz’ New Jersey 9/11 Me- morial in Liberty State Park.