A Qualitative Approach on Motives and Aspects of Risks in Freeriding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wilderness Adventurous Skiing

22 | Sport BRIDGE | December | 2009 BACK TO THE WILDERNESS ADVENTUROUS SKIING If traditional skiing is not for covered landscape, there is a wilder version of wild landscape – which can be both flat or very you and you want more of an cross-country skiing for you. In backcountry, steep. You need lighter downhill skis, special andrenaline rush from your you ride over flat land or mild hills, not binding which can be used both for downhill winter sports, perhaps you should following marked paths. You need comfortable skiing and for going uphill, and special boots, consider some other versions warm boots and cross-country skis with free- lighter and softer than usual ski boots and of an old favourite. How about heel bindings. having a solid sole, so they can be used even freeriding, backcountry or even for walking. Another handy thing is the skins ski touring? Though they require Ski touring you attach to the bottom of skis to be able to go different equipment and different When you set out on a longer trip, this sport uphill without sliding down. In the past, they techniques, they have one thing in is called ski touring. In ski touring, you do not used to be made from animal skins, now they common: They take people from use ski lifts, you just travel on skis over the are made from nylon. the marked ski runs and return them to the dangerous wilderness. CZECH CHAMPIONS Freeriding Radek Groh Freeriding is the easiest way of skiing in natural terrain. It means going down Brother and sister Karolína unmarked slopes, usually on freshly fallen and Radek Groh have been snow called powder. -

The Winter Opportunist

Official Publication of the National Ski Patrol nsp.org + Summer 2017 + Volume 34 Issue 3 WBR DOG SCHOOL THE BEST JOB The Winter Opportunist Nano-Air® Hoody: The warm, stretchy, breathable, cold-weather opportunist When the mercury dips, then drops, the only cold that should force you inside should involve a box of tissues and some heavy-duty decongestants. For everything else, there’s the Patagonia Nano-Air Hoody, a soft, stretchy, revolutionary layer that’ll keep you comfortable (not roasting) during stop-and-go winter missions. Whether you’re skinning like a dog, postholing up a couloir or charging powder, it’s as ready as you are for any winter opportunity. The Nano-Air Hoody is a part of Patagonia’s Opportunist Collection: essential, enduring pieces for any kit, any activity. Patagonia is an official supplier to the National Ski Patrol (NSP) and offers NSP members pro pricing on Patagonia gear. To shop, just visit nsp.org and click on the Patagonia logo within the Pro Deals section of Member Services. PATAGONIA.COM/OPPORTUNIST Benny the powder hound drafts Jasmin Caton as she breaks trail at Valhalla Mountain Touring. British Columbia. KEN ETZEL © 2016 Patagonia, Inc . Mark Welsh p: Sage Cattabriga-Alosa Introducing the Quantum. Aerocore™ construction featuring Koroyd® for the ultimate protection. The experience is everything.™ NSP.ORG 3 THE BEST 32 JOB BY KIM KIRCHER Having patrolled at Crystal Mountain in Washington for many years, Kim Kircher was appointed patrol director in March S 2016. She discusses her many years of experience and what she has tried to do as the director, and how being a woman has RE informed those decisions. -

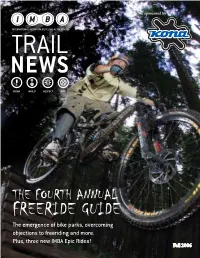

Freeride Guide 04

sponsored by THE FOURTH ANNUAL FREERIDE GUIDE The emergence of bike parks, overcoming objections to freeriding and more. Plus, three new IMBA Epic Rides! Fall 2006 Out of the Shadows Richard Cunningham Editor-at-Large, Mountain Bike Action magazine Years ago, hardcore mountain bikers disappeared into the rainforests of the Pacific Northwest to build log rides and ladder bridges over the tangled forest floor. The sport of freeriding has since emerged from the shadows, and mountain biking is much richer for it. All of us, at least once, have been swept by the burst of exhilaration that follows the first successful passage of a once-impossible section of trail. Freeriding provides unprecedented opportunities for that experience. Mountain bikers have always pushed the boundaries of what can be ridden on two wheels. Who hasn’t paused at the edge of a precipice, however small, to watch a better bike handler give it a go, or mustered the courage to ride a section that we once walked. Freeriders have honed the sport’s challenging aspects into a lifestyle. The risk and intensity may exceed anything that the average rider would choose to face, but the core experience is the same. Well, almost. “Freerider” also describes a professional cyclist in jeans and a T-shirt, upside down, 30 feet above a televised crowd, gapping the space between wooden towers plastered with advertisements. It can be argued that daredevils jumping highways, or launching from obscenely huge stunts aboard 10-inch-travel monster bikes have as much in common with exploring the woods on a hardtail as the Stealth Bomber relates to a crow. -

Freeride / Ski Touring Rates Full Qualified Swiss Ski Instructor: Ski Touring Until Level WS Or Freeriding Until Level ZS (Level According the Swiss Alpine Club)

Low season 30.11.2020-19.12.2020 High season 20.12.2020-13.01.2021 14.01.2021-06.02.2021 07.02.2021-07.03.2021 08.03.2021-25.04.2021 Private rates / Alpine skiing, telemark skiing, cross country skiing, snowboarding Prices are for 1 to 2 persons per day, extra person will be charged CHF 40.00 per day. PRIVATUNTERRICHT Low seson High season All day CHF 390.00 CHF 450.00 2 hours, start 09.00 I 10.00 I 11.00 I 12.00 I 13.00 CHF 190.00 CHF 250.00 2 hours “late bird” 14.00 – 16.00 CHF 160.00 CHF 180.00 2 hours“early bird” 08.00 – 10.00 CHF 160.00 CHF 180.00 *NEW 2 hours last minute flex CHF 150.00 CHF 170.00 Additional hour CHF 100.00 CHF 120.00 *you can book your lesson last minutes (max. 24 hours before lesson), the schedules and choice of instructor is arranged by management of PassionSki. Freeride / Ski touring rates Full qualified Swiss ski instructor: Ski touring until level WS or freeriding until level ZS (Level according the Swiss Alpine Club). Full qualified mountain guide IFMGA: Ski touring or Freeriding at most levels. FREERIDE / SKI TOURING private Price per day Ski instructor “freeride guide” 1 to 2 persons CHF 490.00 Mountain guide IFMGA, 1 to 2 persons CHF 645.00 FREERIDE / SKI TOURING groups Price per person and day Mountain guide IFMGA, 4 to 6 persons CHF 160.00 ABS equipment rental, per day CHF 40.00 Group rates (11.01.2021-05.04.2021) / instructor sharing for adults (children on request only) Monday to Friday from 9.40 until 9.55 am we meet for coffee at Corviglia in the AUDI QUATTRO BAR. -

My First Heliski Day Gressoney Monte Rosa - 2021

My first Heliski day Gressoney Monte Rosa - 2021 Your first heliski day! Our program "My first heliski day", the perfect start up for those who want to try this fascinating way of skiing and snowboarding. Gressoney, on the south side of the Monte Rosa, is the gateway to paradise for skiers, snowboarders and freeriders, offering every day new experiences. All this in one of the most beautiful mountain landscapes in the Alps. Our heliski area extends from the Matterhorn, crossing the Breithorn massif until the southeast side of Monte Rosa. With over 20 landing sites, more than 60 runs and the unique mountain scenery, the area is one of the most spectacular and varied heliski area of the Alps. In the Monte Rosa everybody will find independently of snow-, avalanche- and weather-conditions, the perfect terrain and unique experiences. Why to Gressoney with the Heli Guides Group: For more than 20 years, the team of Heli-Guides and Guidemonterosa operates, we love skiing, freeriding and we have been working in this industry for decades, at first-class heli-skiing locations around the world. Gressoney, our home base, has been the starting point of our story. We know what it takes to build an awesome heliski trip. Working exclusively with our Partners, Heli Guides and Guidemonterosa are able to provide tailor-made heli-skiing holidays, always maintaining our emphasis on flexibility and individuality. We focus on small groups in order to ensure high-end service. Our highly experienced IFMGA/UIAGM guides will select the best descents according to the snow conditions and your ability. -

Dear Alpine Ski Racing Nations

Dear Alpine Ski Racing Nations, The Audi quattro Winter Games NZ returns for its fifth edition from 25 August to 10 September 2017. Running 5 months prior to the PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Winter Games, the best winter sports athletes in the world will once again descend on New Zealand’s South Island for an action packed programme of alpine ski racing, cross country skiing, curling, Ice hockey, big mountain freeriding, freeskiing and snowboarding. The 2017 competition schedule has extended to 2 weeks, moved a week later than previous years and sees the addition of a FWQ Freeride series for the first time at The Remarkables, as well as the return of para-snowboarding with a Para World Cup Banked Slalom at Treble Cone. The Merino Muster is also joining the Games for the first time as an associate Cross Country race. We are delighted to invite all nations to the FIS Alpine Australia New Zealand Continental Cup which takes place at Coronet Peak, NZ. The nearest township from Coronet Peak is Queenstown (13km, 20 minute drive). Queenstown is also the nearest major airport. Entries for the FIS Alpine Ski Racing Australia New Zealand Cup Races are open now via the Coronet Peak Race Secretary. Please find the athlete and team information below. For further information please contact Hannah Hazeldine, Alpine Manager on [email protected] We look forward to welcoming you to Wanaka and the Audi quattro Winter Games New Zealand. Kind regards Arthur Klap Chief Executive The5th edition of the Invitation contents Key Dates and Venues 4 Audi quattro -

Does Age Matter? a Qualitative Comparison of Motives and Aspects of Risk in Adolescent and Adult Freeriders

©Journal of Sports Science and Medicine (2020) 19, 112-120 http://www.jssm.org ` Research article Does Age Matter? A Qualitative Comparison of Motives and Aspects of Risk in Adolescent and Adult Freeriders Anika Frühauf , Julian Zenzmaier and Martin Kopp University of Innsbruck, Department of Sport Science, Austria consumers mostly aged between 10 to 24 years (Bennett et Abstract al., 2003). The growing media attention and financial in- Recent research has shown multiple motives for high-risk sport dustry together with improved technologies could be con- participation derived from research on adult participants. The aim tributing to a new shift in sport participation away from of this study was to provide insights into motives and risk-related traditional sports towards more adventure based sports in- aspects in adolescent high-risk sport participants and to compare volving a certain amount of risk (Mei-Dan, 2018). those findings with adults performing the same activity. Semi- structured interviews were conducted with 24 adolescent (14-20 Conceptualization of high-risk sports and freeriding years) freeriders (skiers/snowboarders who ski outside the pro- Adventure sports (Heggie and Caine, 2012; Kerr and tected areas of a ski resort) and 24 adult freeriders (26-41 years). Houge Mackenzie, 2012), action sports (Bennett et al., A content analyses was done using MAXQDA software. Both co- horts reported the motives Challenge (adolescents: 92%, adults: 2003), extreme sports (Pain and Pain, 2005; Brymer and 88%), Freedom/Pleasure (adolescents: 88%, adults: 75%), Schweitzer, 2013a) and high-risk sports (Barlow et al., Friends (adolescents: 88%, adults: 79%) and Balance (adoles- 2013; Woodman et al., 2010; Castanier et al., 2010) are of- cents: 63%, adults: 63%). -

SKI TOURING in NORWAY Ski Touring in USA, France, Spain, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Sweden and Their Perceptions of Norway As a Ski Touring Destination

Knowledge transfer project: SKI TOURING IN NORWAY Ski touring in USA, France, Spain, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Sweden and their perceptions of Norway as a ski touring destination 2017‐2018 Contents Summary and key findings Ski touring France pages 1 – 30 Ski touring Germany, Austria, Switzerland pages 31 – 62 Ski touring Spain pages 63 – 76 Ski touring US pages 77 – 92 Ski touring Sweden pages 93 – 114 Photo: Håvard Myklebust – visitnorway.com Summary and key findings This project is a cooperation between Innovation Norway and NCE Tourism Fjord Norway. The project was conducted by Innovation Norway’s offices in France, Germany, USA, Spain and Sweden in 2017‐18. The project has been done in two phases. First we did a desktop survey scanning the markets’ ski touring tour operators, web sites, organizations, magazines and festivals. Secondly we conducted interviews with the most relevant tour operators in each market. The results are shown in this report. We hope that this report can contribute in the production of high quality ski touring adventures in Norway. Key results and take‐home messages are mentioned in this summary, but we recommend you to read the whole report. Opportunities ‐ There is an increased interest for ski touring in France, Germany, Spain and Sweden. In USA, the demand seems to remain stable. ‐ Sales of ski touring equipment has increased largely in France, ‐ Ski touring will most likely not become a volume activity, due to high demand of physical abilities, good mountain and snow knowledge and a certain income (France) ‐ In USA, Norway enjoys a strong association with skiing. -

An Exploratory Study of Backcountry Snowboarders

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-01-17 Risk and Reward: An Exploratory Study of Backcountry Snowboarders Plottel, Marcus Plottel, M. (2014). Risk and Reward: An Exploratory Study of Backcountry Snowboarders (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27667 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1262 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Risk and Reward: An Exploratory Study of Backcountry Snowboarders by Marcus Plottel A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2014 © Marcus Plottel 2014 ABSTRACT This study explores and outlines the perceptions of risk of backcountry snowboarders. It addresses backcountry riders’ motivations to voluntarily negotiate hazards in this ostensibly risky recreational activity. Through participant observation and interviews, this work explores how concepts including commercialization and commodification, edgework, and self-control contribute to the identity management of backcountry snowboarders. Importantly, this thesis analyses backcountry snowboarding through the serious leisure paradigm, wherein participation contributes to riders’ perceptions of risk and motivations to continue participation. This work contrasts the risk perceptions of professional backcountry snowboarders with amateur participants, outlining the fundamental differences in their experiences of voluntary risk in this activity. -

Tarvisio 16 Sella Nevea/Bovec 17 Sauris, Forni Avoltri, Paluzza 18 Piani Di Casa - Val Pesarina, 19 Valbruna - Valsaisera, Claut - Valcellina

WINTER WONDERS CREDITS PHOTO: L. Gaudenzio, Pentaphoto, C. Spaliviero, Costerni A different snow experience 3 PRINT: Poligrafiche San Marco - Cormons GRAPHIC DESIGN: Interlaced Srl - Udine Alpine skiing 4 Flying 5 Up high 6 Cross-country skiing 7 Playing 8 Fantasies on ice 9 Snow and fun 10 Skiing and more 11 Everybody skiing 12 Piancavallo 13 Forni di Sopra 14 Ravascletto/Zoncolan 15 Tarvisio 16 Sella Nevea/Bovec 17 Sauris, Forni Avoltri, Paluzza 18 Piani di Casa - Val Pesarina, 19 Valbruna - Valsaisera, Claut - Valcellina AUSTRIA AUSTRIA Ravascletto/Zoncolan Tarvisio Sauris Arta Terme AUSTRIA Forni di Sopra Sella Nevea/Bovec A23 Tolmezzo AUSTRIA Ravascletto/Zoncolan Gemona Tarvisio Sauris SLOVENIAArta Terme Dolomiti Friulane del Friuli Europa Forni di Sopra Sella Nevea/Bovec A23 Tolmezzo San Daniele Cividale Italia Piancavallo del Friuli del Friuli Regione Spilimbergo Gemona del Friuli SLOVENIA Friuli Venezia Giulia Dolomiti FriulaneUDINE SLOVENIA Europa Palù di Livenza PORDENONE Palmanova San Daniele Cividale Italia Piancavallo GORIZIA A28 del Friuli del Friuli Regione SpilimbergoA4 TREVISO Aeroporto FVG Friuli Venezia Giulia UDINE SLOVENIA Palù A4di Livenza Ronchi dei Legionari PORDENONEAquileia VENEZIA Palmanova GORIZIA A28 SLOVENIAA4 TREVISO Lignano Grado Aeroporto FVG Sabbiadoro TRIESTEA4 Ronchi dei Legionari Aquileia VENEZIA SLOVENIA Lignano Grado Sabbiadoro TRIESTE By CAR By PLANE By TRAIN Highways International Airport of Trieste www.trenitalia.it A4 Torino - Trieste 40 km from Trieste and Udine Call Center 89.20.21 A23 Palmanova - Udine - Tarvisio 15 km from Gorizia A28 Portoguaro - Conegliano 80 km from Pordenone www.aeroporto.fvg.it 2 Friulian Dolomites, Carnic Alps and Julian Alps. From Piancavallo and Valcellina, crossing Carnia, up to the Tarvisio area: in Friuli Venezia Giulia it is still possible to ski far from crowds and noise. -

FREERIDING - NEWSCHOOL - FUN - Funsport Day (E.G

2019/2020 EN A WORLD OF FUN FOR CHILDREN HOPPLPARK - Every Tuesday Smiley day daily 9:30 am – 3:00 pm, excluding Saturdays www.skischule-arlberg.com - Every Wednesday Hoppl Skiing day Warm-Up Room, Wigwam, Button Lift, Magic Carpets - Every Thursday Magic-day with a great magic Show in the Hoppl-house - Every Friday Children ski race with Price giving FREERIDING - NEWSCHOOL - FUN - Funsport day (e.g. Skifox, Snowblade, Y Snowbike, Snowsails) PP The freestyle programme is just for advanced skiers and A snowboarders! Skiing and snowboarding in all areas and SPECIALS H snow conditions is just as important to this programme as deep snow skiing, mogul pistes and race training. - Funslope: with bridges, spirals, tunnel, The kids will also be introduced to our Freeride small jumps, steep turns, snow waves and more. and Freestyle programmes. - Stanton Park Trend sports such as - Race track New School, Ski Fox - Hoppl Trail: Learn and discover with our mascot and Snow Bike are HOPPL! Children can learn the FIS Rules along the track also included and look out for the hidden animals in the Hoppl Woods. - Hoppl Pass and Freistil Pass - Hoppl-house CHILDREN’S WORLD ST. CHRISTOPH T +43(0)5446-2151 Magic Carpets, Fairytale Playground, Button Lift, Playroom Note: Only small groups! – separate folder CHILDREN’S WORLD ST. ANTON CHILDREN’S WORLD NASSEREIN daily 9:00 am – 4:00 pm, excluding Saturdays T +43(0)5446-3411-27 daily 9:00 am – 4:00 pm, excluding Saturdays Kindergarten, Magic Carpets, Fort, Hoppl Express, T +43(0)5446-2738 Children’s World Restaurant, Fairytale Playground, Hoppl’s Pirate Restaurant, Assorted Magic Carousel Location: opposite Gampen chairlift Carpets, Fairytale Playground next to the base station of the Nassereinbahn. -

Psychological Variables Related to Developmental Changes During Adolescence—A Comparison Between Alpine and Non-Alpine Sport Participants

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Psychological Variables Related to Developmental Changes during Adolescence—A Comparison between Alpine and Non-Alpine Sport Participants Martin Niedermeier * , Claudia Kogler, Anika Frühauf and Martin Kopp Department of Sport Science, University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] (C.K.); [email protected] (A.F.); [email protected] (M.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 September 2020; Accepted: 26 October 2020; Published: 27 October 2020 Abstract: Alpine sport is a popular form of exercise and provides several skills that are potentially relevant for positive development during adolescence. However, empirical data on differences between alpine and non-alpine sport participants in variables related to developmental changes are lacking. Therefore, the primary aim of the present study was to analyze differences in self-esteem and additional variables between adolescent alpine and non-alpine sport participants. A comparison to non-regular exercisers was conducted for self-esteem. In a cross-sectional design, information on self-esteem, sensation seeking, agency, and emotion regulation was collected in 183 adolescents [(mean age: 15.4 (SD: 2.3) years, 71.0% female)]. Alpine sport participants reported significantly higher self-esteem compared to non-regular exercisers, p = 0.003, d = 0.95, but not compared to non-alpine sport participants, p = 0.774, d = 0.06. When controlling for sex and high-risk sport engagement, alpine sport participants showed a significantly higher experience of agency compared to non-alpine sport participants, p = 0.016, d = 0.46. We conclude that alpine sport participation is less relevant with regard to self-esteem compared to regular exercise.