The Unsolved Murder of JFK's Mistress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cameto Rysticjue

Cameto rysticjue The Am inued Skis• m " Camelot's Mystique: The American Public's Continued Fascination With the Kennedy Assassination By LynDee Stephens University of North Texas Capstone Honors Thesis Spring 1999 h t /l/^ Gloria Cox, university honors program director Richard Wells, journalism department chairman Amid the tract homes and two-car garages that peppered the American landscape in the decade following World War II, there was a controversy brewing, one that could not be contained by government or society. Though America in the 1950s appeared on the surface an ideal society full of hardworking men and happy housewives, it was then that the first strains of the tension that would split the nation over age, morals and race in the 1960s began. It was in this climate, too, that a young, charismatic senator from Massachusetts began a rise to power that ended in his assassination in November 1963 and drew a nation into the mystique of a presidency that would hold widespread fascination for more than a quarter-century. John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, on May 29,1917. His parents, Joseph and Rose Kennedy, were a wealthy and politically active couple. Joe Kennedy was a United States ambassador with high hopes for the family's future. Rose, in particular, had watched her Jiusband's rise in the international arena and had big plans for her nine children, of which John was the second boy (Patterson, 1). John grew up on the family's New England estate as a young man with big ideas. He attended Princeton University briefly in the late 1930s before transferring to Harvard in 1936, where he would graduate in 1940. -

Vol 3, No 14.Jpg

IULY 16-:11, 1996 Ken Silverstein & Alexander Cockburn VOL. 3, NO. 14 • IN THIS ISSUE Oil in Its Hours of Triuniph robed by public interest groups, drop inc.endiary bombs and burn o£fthe Special Summer the Democratic candidate for the sliclc, hopefully before the goop fetches Reading Issue Ppresidential nomination agrees up on · the shores of the Mak.ah and that he will: Quinault Indian reservations. • Break up the oil cartel, dominated Billed by proud government flacks as The Murder of Mary by the Seven Sisters, ;,.hose Ameri an enviro wargame, this mad exercise Meyer: A Mystery · . ·' -· ·can members are Texaco, Chevron, actually represents unconditional sur from Babylon's Past Mobil, Exxon, and ARCO. render to the oil industry . What ,re have • Prohibit oil and gas companies here is taxpayer money underwriting in • A Killing on the from simultaneously controlling dustry efforts to persuade the public .Canal Towpath . ~ther energy sources such as coal (which maintains .a healthy loathing for and natural gas. Big Oil) that drilling in the most ecologi • Nationalize the development 0£ all cally sensitive areas is just line, and that • A Nod and a Winlc oil and gas reserves on federally even the worst disaster can be swiftly Did Joseph Kennedy owned, public lands. cleaned up. Order Her Death? • Curb corporate profits from public There is every reason for the public to leases, particularly oil companies be skeptical of the oil companies' good • Hijinks on the High Seas: drilling on the outer continental intentions. An independent counsel who JFK and Mrs. Niven shelf. investigated the Department of Interior's • Oppose deregulation 0£ the oil and oil leasing practices put together a report gas industry. -

Benjamin C. Bradlee

Benjamin C. Bradlee: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Bradlee, Benjamin C., 1921-2014 Title: Benjamin C. Bradlee Papers Dates: 1921-2013 Extent: 185 document boxes, 2 oversize boxes (osb) (77.7 linear feet), 1 galley file (gf) Abstract: The Benjamin C. Bradlee Papers consist of memos, correspondence, manuscript drafts, desk diaries, transcripts of interviews and speeches, clippings, legal and financial documents, photographs, notes, awards and certificates, and printed materials. These professional and personal records document Bradlee’s career at Newsweek and The Washington Post, the composition of written works such as A Good Life and Conversations with Kennedy, and Bradlee’s post-retirement activities. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-05285 Language: English and French Access: Open for research. Researchers must register and agree to copyright and privacy laws before using archival materials. Some materials are restricted due to condition, but facsimiles are available to researchers. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases, 2012 (12-05-003-D, 12-08-019-P) and Gift, 2015 (15-12-002-G) Processed by: Ancelyn Krivak, 2016 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Bradlee, Benjamin C., 1921-2014 Manuscript Collection MS-05285 Biographical Sketch Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee was born in Boston on August 26, 1921, to Frederick Josiah Bradlee, Jr., an investment banker, and Josephine de Gersdorff Bradlee. A descendant of Boston’s Brahmin elite, Bradlee lived in an atmosphere of wealth and privilege as a young child, but after his father lost his position following the stock market crash of 1929, the family lived without servants as his father made ends meet through a series of odd jobs. -

To Identify and Honor Great Neck's Most Notable Homes ONE COVE LANE, KINGS POINT, NY

HERITAGE RECOGNITION PROGRAM To Identify and Honor Great Neck’s Most Notable Homes ONE COVE LANE, KINGS POINT, NY he home at One Cove Lane is the former carriage house, stables, hayloft T and water tower built c. 1879 on the property of “The Cove,” an eleven- acre estate on West Shore Road owned by Cord Meyer II (185 4 –1910) and his wife, Cornelia Meyer (185 6–1939). “The Cove” was their main residence, built on the shorefront of what is now Cove Lane. Cord Meyer II was the son of a German immigrant, Cord Meyer, of Dick & Meyer, an old firm that refined sugar in Cuba. On his father’s death, c . 1891, Cord Meyer II inherited a portion of his father’s $7,000,000 fortune. He became a wealthy financier, industrialist and developer of large tracts of land, including the areas now known as Elmhurst and Forest Hills. He was active in politics, serving as Chairman of the New York State Democratic Party. His friends included President Grover Cleveland. Cord Meyer II’s son, Cord Meyer, Sr. (1895–1964), was a senior diplomat and real estate developer. He is listed as one of the original Early Birds of Aviation, a group of pioneer pilots who flew solo before 1917. His grandson, Cord Meyer, Jr. (1920–2001) fought in the assault on Guam with the U.S. Marine Corps, and was awarded the Purple Heart and Bronze Star. His dispatches from the war were published in The Atlantic Monthly , and one of his short stories won the O. -

What the Eulogists Didn't Tell You About Katie Graham and the {Post}

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 28, Number 32, August 24, 2001 Book Review What the Eulogists Didn’t Tell You About Katie Graham and the Post by Edward Spannaus A most useful antidote to this falsification of history, is the book Katharine the Great by Deborah Davis. Two aspects Katharine The Great: Katharine Graham of it must be considered. First, what Davis wrote about the And Her Washington Post Empire Post and its relationship to U.S. intelligence community. And by Deborah Davis second, what happened when Davis tried to first publish the New York: Sheridan Square Press, 1991 (third edition) book in 1979. 322 pages paperbound, $14.95 In her preface to the third edition, Davis writes: “This is the third It would be hard to exceed the hypocrisy of the days following edition of a book origi- the official announcement of the death of Katharine Graham nally written shortly on July 17. Even in death, Graham still had the power to after President Nixon re- make those, otherwise considered powerful in their own right, signed as a result of the grovel at her feet. Washington Post’s in- Eulogy after eulogy cited Graham’s alleged courage, and vestigation of the Water- even gutsiness, with respect to two publishing events: the gate scandal. The con- Pentagon Papers, and Watergate. In both cases, the truth is ceptual center of the directly contrary to the legend. In both cases, the Post was book is the question: spoon-fed material from a section of the U.S. intelligence Could Katharine Gra- community, designed to discredit President John F. -

Mary's Mosaic (Book Review) (Summer 2012)

Mary’s Mosaic The CIA conspiracy to murder John F. Kennedy, Mary Pinchot Meyer and their vision for world peace Peter Janney New York: Skyhorse, 2012, $26.95, h/b Mary Pinchot Meyer is one of the footnotes to the Kennedy assassination. She married future CIA bigwig Cord Meyer in 1945 and their social circle in the 1950s included many of Washington’s ruling elite. As far as it was then possible for a woman to be an insider, she was one. She was good-looking, talented and financially independent. After divorcing Meyer in 1958 she became a bit of a bohemian amongst the Wasps of Georgetown – a painter, a doper and an LSD user. She might have lived a long and interesting life had she not become one of JFK’s lovers and joined the list of those linked to the Dallas event who died a violent death. She was shot in Washington in 1964 while taking her daily walk along a canal towpath. The Washington police duly arrested the nearest available black male and tried to convict him of her death. Thanks to spectacularly sloppy police work and a very good defence lawyer, the frame failed. Meyer surfaced in Timothy Leary’s memoir Flashbacks with Leary’s account of phone calls from Meyer talking of smoking dope with JFK in the White House and forming a kind of LSD conspiracy with some female friends, to turn on the powerful men of the Washington elite.1 Meyer was also one of the people who knew enough about Washington and its secrets not to believe the Warren Commission’s account of the murder of her lover. -

Mary Pinchot Meyer

THE MURDER MARY PINCHOT MEYER Socialite, mistress of JFK, wife of CIA official, Ben Bradlee's tenant and sister-in- law, and victim of a terrible conspiracy. By Timothy Leary rom 1960 to Charles Mingus, Miles Davis, John Len- 1967 I was di- non, Jim Morrison; philosophers like Al- rector of re- dous Huxley, Arthur Koestler, Alan Watts; search projects swamis, gurus, mystics, psychics by the at Harvard Uni- troops. Scores of scientists from top uni- versity and Mill- versities. And, occasionally steely-eyed ex- brook, New perts, from government and military York which centers also participated. studied the ef- It was not until the Freedom of Informa- fects of brain- tion Act of the Carter administration that change drugs. we learned that the CIA had spent 25 mil- During this pe- lion dollars on brain-change drugs, and that riod a talented the U.S. Army at Edgewater Arsenal in group of psy- Maryland had given LSD and stronger psy- chologists and chedelic drugs to over 7000 unwitting, un- philosophers on our staff, ran guided informed enlisted men. "trips" for over 3000 volunteers. These The most fascinating and important of projects won world-wide recognition as these hundreds of visitors showed up in the centers for consciousness alteration and Spring of 1962. I was sitting in my office at exploration of new dimensions of the mind. Harvard University one morning when I Our headquarters at Harvard and Mill- looked up to see a woman leaning against brook were regularly visited by people in- the door post, hip tilted provocatively, terested in expanding their intelligence--- studying me with a bold stare. -

JFK Was the Wrong Man in the Wrong Place at the Wrong Time

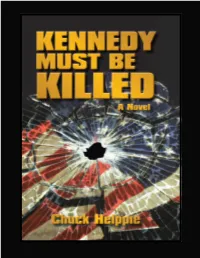

www.kennedymustbekilled.com “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” — George Santanya John F. Kennedy was headed down a path to failure the moment his family stole the 1960 presidential election. Patrick McCarthy knew that JFK was the wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time. He had witnessed years of poor judgment and appall- ingly bad behavior by Jack and his family, and it both concerned and sickened him. Cold War tensions were overheating, and he knew Jack Kennedy couldn't possibly stand up under its pressures. He wasn't alone in those thoughts. The Kennedys had made many enemies over the years and the political power struggle that had been long brewing was now coming to a head. When JFK's numerous foreign policy blunders took the nation to the very brink of nuclear war, and his meddling in civil rights inflamed racial hatreds in the South, a shadowy group of powerful men known as the Patriots decide it is time to act. Kennedy must be stopped before his next mistake resulted in the deaths of millions of innocent Americans. On November 22, 1963, a cruel twist of fate finds Patrick McCarthy concealed on a grassy knoll in Dealey Plaza, cradling a sniper's rifle and waiting patiently for the presidential motorcade to pass by. Spanning the period from 1946-1978, KENNEDY MUST BE KILLED is a meticulously researched novel featuring a wide ranging cast of historical characters, including Jack and Jackie Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Dwight Eisenhower, Allen Dulles, Alger Hiss, Joseph McCarthy, Nikita Khrushchev, J. -

Samuel H. Beer, Oral History Interview – 11/7/2002 Administrative Information Creator: Samuel H. Beer Interviewer: Vicki Dait

Samuel H. Beer, Oral History Interview – 11/7/2002 Administrative Information Creator: Samuel H. Beer Interviewer: Vicki Daitch Date of Interview: November 7, 2002 Place of Interview: Cambridge, Massachusetts Length: 50 pages Biographical Note Beer, a historian, educator, and Massachusetts political figure, was Massachusetts chairman (1955-1957) and later national chairman (1959-1962) of the Americans for Democratic Action. In this interview, he discusses John F. Kennedy’s (JFK) place in the larger Democratic Party and relationship with other Democratic politicians, his stand on social issues and social programs, his extramarital affairs and those of other politicians, and various academics involved with the Kennedy administration, among other issues. Access Open except for a small portion on page 12. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed April 24, 2003, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. -

Anne Truitt Exhibition Wall Text

ANNE TRUITT nne Truitt was one of the leading figures associated with could focus on her art, explaining, “In my studio I feel at home with Aminimalism, the sculptural tendency that emerged in the 1960s myself, peaceful at heart, remote from the world, totally immersed featuring pared-down geometric shapes scaled in a process so absorbing as to be its own reward.” to the viewer’s body and placed directly on the floor. Born in Baltimore in 1921, Truitt grew up in Truitt’s art is unique within the field of minimal- Easton, a town on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. After ism; she alone remained a traditional studio artist. majoring in psychology at Bryn Mawr College and Whereas artists such as Donald Judd (1928�–�1994) marrying the journalist James Truitt, she enrolled and Carl Andre (b. 1935) abandoned the studio in studio classes at the Institute of Contempo - and enlisted industrial fabrication and materials, rary Arts in Washington, DC. Following sojourns Truitt painted and sanded her wood sculptures in Dallas, New York, and by hand in multiple layers. And while many mini- San Francisco, Truitt set- Anne Truitt in Twining Court studio, 1962. © annetruitt.org�/�Bridgeman Images malists favored neutral tones, Truitt, in order to tled in Washington in 1960. Apart from a suffuse her work with memory and feeling, developed a daring stint in Tokyo, 1964�–�1967, the artist lived palette that ranged from deep reds and blacks to pale yellows and and worked in the District until her death lavenders. This exhibition, a survey of Truitt’s sculpture, painting, Anne Truitt’s 35th Street studio, 1979. -

Special Access and FOIA, FOIA Requests For

Case Id Date Received Date Closed Requester Name Subject Disposition Description Department of Justice (DOJ) Case File 169-26-1, Section 1 in box 28 of 48885 Jan/04/2016 Jan/20/2016 Ahmed Young Class 169: Desegregation of Public Education Total grant 48886 Jan/04/2016 Jan/21/2016 Jared Leighton Mark Clark, 44-HQ-44202, 157-SI-802 Request withdrawn Other all FBI personnel and case records for retired Special Agenct Edmund F. 48891 Jan/05/2016 Jan/12/2016 Devin Murphy Murphy who served in DC, NC, Missouri field offices Other Other 48893 Jan/05/2016 Jan/22/2016 (b) (6) (b) (6) Partial grant 48894 Jan/05/2016 Feb/03/2016 Jared McBride IRR files Total grant 48895 Jan/05/2016 Jun/09/2016 Conor Gallagher FBI file numbers 100-AQ-3331 regarding the Revolutionary Union Request withdrawn Other FBI Field Office case files regarding the Revolutionary Union 100-RH-11090 Springfield 100-11574 Richmond 100-11090 48896 Jan/05/2016 Conor Gallagher Dallas 100-12360 FBI file numbers regarding the October League aka Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist) New York 100-177151 Detroit 100-41416 48897 Jan/05/2016 Conor Gallagher Baltimore 100-30603 FBI Case Number 100-HQ-398040, 100-NY-109682, 100-LS-3812. Leon 48900 Jan/06/2016 Jan/26/2018 Parker Higgins Bibb Partial grant FBI Case File 100-CG-42241, 100-NY-151519, 100-NY-150205, 100-BU- 48902 Jan/06/2016 Kathryn Petersen 439-369. FBI Case File 100-HQ-426761 and 100-NY-141495. Nonviolent Action 48903 Jan/06/2016 Mar/02/2016 Mikal Jakubal Against Nuclear Weapons. -

Meyer, Cord Jr

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 January 12, 2017 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. FOIPA Request No.: 1364325-000 Subject: MEYER, CORD JR. Dear Mr. Greenewald: Records responsive to your request were previously processed under the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act. Enclosed is one CD containing 22 pages of previously processed documents and a copy of the Explanation of Exemptions. This release is being provided to you at no charge. Please be advised that additional records potentially responsive to your subject may exist. If this release of previously processed material does not satisfy your information needs for the requested subject, you may request an additional search for records. Submit your request by mail or fax to – Work Process Unit, 170 Marcel Drive, Winchester, VA 22602, fax number (540) 868-4997. Please cite the FOIPA Request Number in your correspondence. For your information, Congress excluded three discrete categories of law enforcement and national security records from the requirements of the FOIA. See 5 U.S. C. § 552(c) (2006 & Supp. IV (2010). This response is limited to those records that are subject to the requirements of the FOIA.