Prison Provision in Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concise Minutes - Health and Social Care Committee

Concise Minutes - Health and Social Care Committee Meeting Venue: This meeting can be viewed Committee Room 3 - Senedd on Senedd TV at: http://senedd.tv/en/3321 Meeting date: Wednesday, 25 November 2015 Meeting time: 09.00 - 12.12 Attendance Category Names David Rees AM (Chair) Peter Black AM (In place of Kirsty Williams AM) Alun Davies AM John Griffiths AM Altaf Hussain AM Assembly Members: Elin Jones AM Darren Millar AM Lynne Neagle AM Gwyn R Price AM Lindsay Whittle AM Kirsty Williams AM, Member in charge of the Safe Nurse Staffing Levels (Wales) Bill Witnesses: Philippa Watkins, National Assembly for Wales Commission Lisa Salkeld, National Assembly for Wales Commission Mark Drakeford AM, The Minister for Health and Social Services Helen Whyley, Welsh Government Rhian Williams, Welsh Government Llinos Madeley (Clerk) Gareth Howells (Legal Adviser) Catherine Hunt (Second Clerk) Committee Staff: Sian Giddins (Deputy Clerk) Gwyn Griffiths (Legal Adviser) Amy Clifton (Researcher) Philippa Watkins (Researcher) Transcript View the meeting transcript. 1 Introductions, apologies and substitutions 1.1 There were no apologies. 1.2 For items relating to the Safe Nurse Staffing Levels (Wales) Bill, Peter Black substituted for Kirsty Williams. 2 Safe Nurse Staffing Levels (Wales) Bill: Stage 2 - consideration of amendments 2.1 Lynne Neagle declared the following relevant interest under Standing Order 17.24A: • She has a close family member currently living on a mental health inpatient ward 2.2 In accordance with Standing Order 26.21, the Committee disposed of the following amendments to the Bill: Amendment 28 (Mark Drakeford) In favour Against Abstain Alun Davies Altaf Hussain Peter Black John Griffiths Darren Millar Elin Jones Lynne Neagle Gwyn R Price David Rees Lindsay Whittle Amendment 28 was agreed. -

Partnership Council for Wales - Forward Work Programme

Partnership Council for Wales - Forward Work Programme 20 September 2018 Topics Minister’s Portfolio Local Government Reform – including emerging findings of the community and town councils review Alun Davies AM Cabinet Secretary for Local Government and Public Services Digital Julie James AM Leader of the House and Chief Whip European Transition Mark Drakeford AM Cabinet Secretary for Finance December 2018 Topics Minister’s Portfolio Local Government Finance Settlement Alun Davies AM Cabinet Secretary for Local Government and Public Services The Future of Local Government Finance Alun Davies AM Cabinet Secretary for Local Government and Public Services Mark Drakeford AM Cabinet Secretary for Finance Local Government Partnership Scheme Annual Report 2017- 2018 Alun Davies AM Cabinet Secretary for Local Government and Public Services The Welsh Language Strategy Eluned Morgan AM Minister for Welsh Language and Lifelong Learning March 2019 Topics Minister’s Portfolio Public Service Boards Alun Davies AM Cabinet Secretary for Local Government and Public Services Natural Resources Policy Hannah Blythyn AM Minister for Environment Integration of Health and Social Care Vaughan Gething AM Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Services 1 July 2019 Topics Minister’s Portfolio Development of the community planning model at the town planning level Alun Davies AM Cabinet Secretary for Local Government and Public Services An update on the Well-being of Future Generations Act / PSBs Mark Drakeford AM Cabinet Secretary for Finance Violence against women and girls Julie James AM Leader of the House and Chief Whip 2 . -

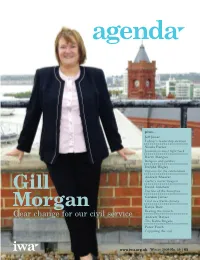

Gill Morgan, Is Dealing with Whitehall Arrogance

plus… Jeff Jones Labour’s leadership election Nicola Porter Journalism must fight back Barry Morgan Religion and politics Dafydd Wigley Options for the referendum Andrew Shearer Garlic’s secret weapon Gill David Culshaw Decline of the honeybee Gordon James Coal in a warm climate Morgan Katija Dew Beating the crunch Gear change for our civil service Andrew Davies The Kafka Brigade Peter Finch Capturing the soul www.iwa.org.uk Winter 2009 No. 39 | £5 clickonwales ! Coming soon, our new website www. iwa.or g.u k, containing much more up-to-date news and information and with a freshly designed new look. Featuring clickonwales – the IWA’s new online service providing news and analysis about current affairs as it affects our small country. Expert contributors from across the political spectrum will be commissioned daily to provide insights into the unfolding drama of the new 21 st Century Wales – whether it be Labour’s leadership election, constitutional change, the climate change debate, arguments about education, or the ongoing problems, successes and shortcomings of the Welsh economy. There will be more scope, too, for interactive debate, and a special section for IWA members. Plus: Information about the IWA’s branches, events, and publications. This will be the must see and must use Welsh website. clickonwales and see where it takes you. clickonwales and see how far you go. The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges core funding from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust , the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation . The following organisations are corporate members: Private Sector • Principality Building Society • The Electoral Commission Certified Accountants • Abaca Ltd • Royal Hotel Cardiff • Embassy of Ireland • Autism Cymru • Beaufort Research • Royal Mail Group Wales • Fforwm • Cartrefi Cymunedol / • Biffa Waste Services Ltd • RWE NPower Renewables • The Forestry Commission Community Housing Cymru • British Gas • S. -

Sentencing and Immediate Custody in Wales: a Factfile

Sentencing and Immediate Custody in Wales: A Factfile Dr Robert Jones Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University January 2019 Acknowledgements ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would especially like to thank Lucy Morgan for all of her help in producing this report. I would also like to thank staff working at the Ministry of Justice who have responded to the many requests for information made during the course of this research. Finally, I am extremely grateful to Alan Cogbill, Emyr Lewis, Ed Poole, Huw Pritchard and Richard Wyn Jones for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of this report. ABOUT US The Wales Governance Centre is a research centre that forms part of Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics undertaking innovative research into all aspects of the law, politics, government and political economy of Wales, as well the wider UK and European contexts of territorial governance. A key objective of the Centre is to facilitate and encourage informed public debate of key developments in Welsh governance not only through its research, but also through events and postgraduate teaching. In July 2018, the Wales Governance Centre launched a new project into Justice and Jurisdiction in Wales. The research will be an interdisciplinary project bringing together political scientists, constitutional law experts and criminologists in order to investigate: the operation of the justice system in Wales; the relationship between non-devolved and devolved policies; and the impact of a single ‘England and Wales’ legal system. CONTACT DETAILS Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University, 21 Park Place, Cardiff, CF10 3DQ. Web: http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/wgc/ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Robert Jones is a Research Associate at the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University. -

Christina Rees MP Report

MONTHLY REPORT 20 OCTOBER 2017 Christina Rees MP Monthly Report - October 2017 It was wonderful to see the return of Neath Food and Drink Festival this year, where local producers and the town were Rhianna’s Swing Visits Parliament showcased. Local charity raises awareness of important project Rhianna Chellew was just 8 years old when she was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumour which quickly resulted in her being wheelchair bound. Rhianna’s parents took her to Ynysanghared Park in Pontypridd, which has a disabled access swing. It meant the world to her to be able to join her able-bodied friends on some of the equipment. She enjoyed so much that her parents looked for other playgrounds with similar equipment but I was delighted to there were not any in Wales. support the “Wear It Pink” campaign to Heartbreakingly, Rhianna passed away surrounded by her family on the 23rd raise awareness of June 2016. As a legacy, family and friends have set up “Rhianna’s Swing” a breast cancer charity aiming to source funding to establish a fully accessible play area in Gnoll Park. Keen to support the project, Christina has been working to raise awareness (and help raise funds), including hosting an MP’s drop-in in Parliament, which was attended by members from across both Houses. THE GREAT SEPTEMBER FAIR IN NEATH The 737th Great September Fair arrived in Neath to yet another warm welcome and I was very happy to massive crowds. Apart from a torrential pledge my support downpour on the Saturday, the week was blessed with fine weather, drawing in people for British and from afar and raising Neath’s profile. -

Cofnod Pleidleisio Voting Record 06/05/2015

Cofnod Pleidleisio Voting Record 06/05/2015 Cynnwys Contents NDM5750 Dadl y Ceidwadwyr Cymreig - Cynnig heb ei ddiwygio NDM5750 Welsh Conservatives Debate - Motion without amendment NDM5750 Gwelliant 1 NDM5750 Amendment 1 NDM5750 Gwelliant 2 NDM5750 Amendment 2 NDM5750 Gwelliant 3 NDM5750 Amendment 3 NDM5750 Gwelliant 4 NDM5750 Amendment 4 NDM5750 Dadl y Ceidwadwyr Cymreig - Cynnig fel y'i diwygiwyd NDM5750 Welsh Conservatives Debate - Motion as amended NDM5752 Dadl y Ceidwadwyr Cymreig - Cynnig heb ei ddiwygio NDM5752 Welsh Conservatives Debate - Motion without amendment NDM5752 Gwelliant 1 NDM5752 Amendment 1 NDM5752 Dadl y Ceidwadwyr Cymreig - Cynnig fel y'i diwygiwyd NDM5752 Welsh Conservatives Debate - Motion as amended NDM5751 Dadl Plaid Cymru - Cynnig heb ei ddiwygio NDM5751 Welsh Plaid Cymru Debate - Motion without amendment Cofnod Pleidleisio | Voting Record | 06/05/2015 Senedd Cymru | Welsh Parliament NDM5750 Dadl y Ceidwadwyr Cymreig - Cynnig heb ei ddiwygio NDM5750 Welsh Conservatives Debate - Motion without amendment Gwrthodwyd y cynnig Motion not agreed O blaid / For: 10 Yn erbyn / Against: 23 Ymatal / Abstain: 0 Mohammad Asghar Leighton Andrews Peter Black Mick Antoniw Andrew R.T. Davies Christine Chapman Paul Davies Jeff Cuthbert Suzy Davies Alun Davies Russell George Jocelyn Davies William Graham Keith Davies Darren Millar Mark Drakeford Nick Ramsay Rebecca Evans Aled Roberts Janice Gregory Llyr Gruffydd Edwina Hart Mike Hedges Julie James Elin Jones Huw Lewis Sandy Mewies Gwyn R. Price Kenneth Skates Gwenda Thomas Rhodri Glyn Thomas Simon Thomas Lindsay Whittle Cofnod Pleidleisio | Voting Record | 06/05/2015 Senedd Cymru | Welsh Parliament NDM5750 Gwelliant 1 NDM5750 Amendment 1 Gwrthodwyd y gwelliant Amendment not agreed O blaid / For: 16 Yn erbyn / Against: 17 Ymatal / Abstain: 0 Mohammad Asghar Leighton Andrews Peter Black Mick Antoniw Andrew R.T. -

Inquiry Into a Legislative Budget Process

Welsh Parliament Finance Committee Inquiry into a legislative budget process August 2020 www.senedd.wales The Welsh Parliament is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people. Commonly known as the Senedd, it makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this document can be found on the Welsh Parliament website: www.senedd.wales/SeneddFinance Copies of this document can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print, audio or hard copy from: Finance Committee Welsh Parliament Cardiff Bay CF99 1SN Tel: 0300 200 6565 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @SeneddFinance © Senedd Commission Copyright 2020 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the Senedd Commission and the title of the document specified. Welsh Parliament Finance Committee Inquiry into a legislative budget process August 2020 www.senedd.wales About the Committee The Committee was established on 22 June 2016. Its remit can be found at: www.senedd.wales/SeneddFinance Committee Chair: Llyr Gruffydd MS Plaid Cymru Current Committee membership: Alun Davies MS Siân Gwenllian MS Welsh Labour Plaid Cymru Mike Hedges MS Rhianon Passmore MS Welsh Labour Welsh Labour Nick Ramsay MS Mark Reckless MS Welsh Conservatives Brexit Party The following Member was also a member of the Committee during this inquiry. Rhun ap Iorwerth MS Plaid Cymru Inquiry into a legislative budget process Contents Chair’s foreword .................................................................................................... -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Plenary, 09/12/2020 13:30

------------------------ Public Document Pack ------------------------ Agenda - Plenary Meeting Venue: Y Siambr - Y Senedd Meeting date: Wednesday, 9 December 2020 Meeting time: 13.30 310(v5) ------ This meeting will be held in a hybrid format, with some Members in the Senedd Chamber and others joining by video-conference. Having consulted with the Business Committee, the Llywydd has determined that in accordance with Standing Order 34.14A-D, Members will be able to vote from any location by electronic means. The Llywydd also gives notice, in accordance with Standing Order 34.15, that the public have been excluded from attending this Plenary meeting, as is required to protect public health. The meeting will continue to be broadcast live and the record of proceedings will be published as usual. 1 Questions to the Minister for Economy, Transport and North Wales (45 mins) The Presiding Officer will call party spokespeople to ask questions without notice after Question 2. View Questions 2 Questions to the Counsel General and Minister for European Transition (in respect of his European Transition responsibilities) (45 mins) The Presiding Officer will call party spokespeople to ask questions without notice after Question 2. View Questions 3 Topical Questions (0 mins) No Topical Questions were accepted. 4 90 Second Statements (5 mins) 5 Member Debate under Standing Order 11.21(iv) - Support for babies and new parents during Covid-19 (60 mins) NDM7462 Lynne Neagle (Torfaen) To propose that the Senedd: 1. Recognises that the evidence is unequivocal that the first 1,000 days of a child’s life, from pregnancy to age two, lay the foundations for a happy and healthy life and that the support and wellbeing of babies during this time is strongly linked to better outcomes later in life, including educational achievement, progress at work and better physical and mental health. -

HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales Annual Report 2014–15 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales Annual Report 2014–15

HM Chief Annual Report Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales Annual Report 2014–15 2014 – 15 HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales Annual Report 2014–15 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 5A of the Prison Act 1952 as amended by Section 57 of the Criminal Justice Act 1982. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 14 July 2015. HC 242 © Crown Copyright 2015 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications and www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: [email protected] Print ISBN 9781474122917 Web ISBN 9781474122924 ID 30061511 07/15 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. CONTENTS Who we are and what we do 4 1 Introduction By the Chief Inspector of Prisons 6 2 The year in brief 24 3 Men in prison 28 Safety needs to improve 32 Respect outcomes under pressure -

Roles and Identities of the Anglican Chaplain: a Prison Ethnography

Peter Phillips Roles and identities of the Anglican chaplain: a prison ethnography A thesis submitted in accordance with the regulations for the award of the degree of PhD at Cardiff University November 2013 i DECLARATIONS This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… ii SUMMARY In this ethnography, writing as both practitioner and researcher, I represent and analyse the opinions and reflections of Anglican chaplains in English and Welsh prisons in order to locate their self-perception of role and identity. The Anglican chaplain has been a statutory appointment in every prison since 1779 and was a central figure in penal practice throughout the first half of the 19th century. -

Concise Minutes - Finance Committee

Concise Minutes - Finance Committee Meeting Venue: This meeting can be viewed Committee Room 1 - Senedd on Senedd TV at: Meeting date: Wednesday, 13 November http://senedd.tv/en/5777 2019 Meeting time: 09.31 - 10.51 Private ------ Attendance Category Names Llyr Gruffydd AM (Chair) Rhun ap Iorwerth AM Alun Davies AM Assembly Members: Mike Hedges AM Nick Ramsay AM Mark Reckless AM Laura Fox, Welsh Government Witnesses: Andrew Hewitt, Welsh Government Gareth McMahon, Welsh Government Bethan Davies (Clerk) Leanne Hatcher (Second Clerk) Georgina Owen (Second Clerk) Committee Staff: Samantha Williams (Deputy Clerk) Owen Holzinger (Researcher) Christian Tipples (Researcher) 1 Introductions, apologies, substitutions and declarations of interest 1.1 The Chair welcomed Members and witnesses to the meeting. 1.2 Apologies were received from Rhianon Passmore. 2 Technical briefing: Making changes to Welsh tax legislation 2.1 The Committee received a technical briefing from Gareth McMahon, Government Lawyer; Andrew Hewitt, Welsh Treasury; and Laura Fox, Welsh Treasury on proposed changes to Welsh tax legislation. 3 Public Services Ombudsman for Wales Estimates 2020-21: Consideration of draft report 3.1 The Committee agreed the content of the draft report. 4 Welsh Government Draft Budget 2020-21: Approach to scrutiny 4.1 The Committee considered the revised approach to scrutiny for the Welsh Government draft budget 2020-21 and agreed the way forward. 5 Approach to scrutiny for forthcoming legislation 5.1 The Committee considered the paper on the approach to scrutiny for forthcoming legislation. 6 Annual scrutiny of the Wales Audit Office and the Auditor General for Wales: Consideration of draft report 6.1 The Committee considered the draft report and agreed to consider a revised draft on 27 November 2019.. -

Our Valleys, Our Future 2 Our Valleys, Our Future

#TalkValleys Our Valleys, Our Future 2 Our Valleys, Our Future Contents Chair’s Foreword 4 Introduction: The South Wales Valleys 5 Listening to what the Valleys want 8 Priority 1 9 Good quality jobs and the skills to do them Priority 2 12 Better public services Priority 3 16 My local community Looking Forward 19 3 Our Valleys, Our Future Chair’s Foreword I am delighted to publish Our Valleys, Our Future – I was born and brought up in Tredegar – I went to Tredegar Comprehensive the Ministerial Taskforce for the South Wales Valleys’ School. Today, I have the privilege of representing Blaenau Gwent in the plan. This has been put together after listening to National Assembly. I’ve seen many changes in the Valleys over my lifetime – people living and working in the Valleys. It reflects many of them for the better but some of them for the worse. their hopes and aspirations for the future of their I want this taskforce to make a positive difference, not just to the South Wales families and local communities. Valleys as a whole, but to every person living and working in the Valleys. In July 2016, I was asked by First Minister Carwyn Jones to set up and lead a long-term piece of work, which will deliver real change for the South Wales Our first year has been fast-paced and we have had open, frank and wide- Valleys; which will create good-quality jobs, closer to people’s homes; improve ranging conversations in taskforce meetings as we have listened to and people’s skills and bring prosperity to all.