0303.1.00.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OABC RADIO NETWORKS Please Audition Each Disc Immediately

Please audition each disc immediately. If you have any questions, please contact us at WITH 101 KINGSLEY (213) 882-8330. ABC-WATERMARK 357:, CAHUENGA BL VD W. #555 LOS ANGELES, CA 90068 213.882.8330 or FAX 213.850.1050 TOPICAL PROMOS TOPICAL PROMOS FOR SHOW #50 ARE LOCATED ON DISC 4, TRACKS 6, 7 & 8 DO NOT USE AFTER SHOW 50. 1. BROOKS HOLDS COURT AT fl :23 Hi, I'm Bob Kingsley and last week Garth Brooks was holding court as president of "THE AMERICAN HONKY-TONK BAR ASSOCIATION," and he brought the gavel down on his 13th #1 country hit. Will he sentence himself to spend another week at the top spot, or will some other hot hit parole him from the pinnacle of popularity? Join me this weekend for the verdict on American Country Countdown! (LOCAL TAG) 2. MARTINA JUST ONE AWAY FROM A PAY IN THE #1 SUN :19 I'm Bob Kingsley and currently Martina McBride, is enjoying her greatest chart triumph yet with "MY BABY LOVES ME," which moved up to #2 last week. Greater glory is just one notch away at #1. So find out what happens to Martina and all your other favorites this weekend on American Country Countdown! (LOCAL TAG) 3. LITTLE TEXAS BIG JUMPIN' IN TOP TEN :17 Hi, I'm Bob Kingsley and last week Little Texaa took a Texas size jump from #1 Oto #5 in the nation. A jump just like that could make "GOD BLESSED TEXAS" their first #1 hit', check it out this weekend on American Country Countdown! (LOCAL TAG) ..... -

311 Creatures

311 Creatures (For A While) 10 Years After I'd Love To Change The World 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc The Things We Do For Love 112 Come See Me 112 Cupid 112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 112 Peaches & Cream 112Super Cat Na Na Na 1910 Fruitgum Co. 1 2 3 Red Light 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 2Pac California Love 2Pac Changes 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac How Do You Want It 2Pau Heart And Soul 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down Duck And Run 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Of Hearts Arizon Rain 311 All Mixed Up 311 Amber 311 Down 311 I'll Be Here Awhile 311 You Wouldn't Believe 38 Special Caught Up In You 38 Special Hold On Loosely 38 Special Rockin' Into The Night 38 Special Second Chance 38 Special Wild Eyed Southern Boys 3LW I Do 3LW No More Baby 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3rd Stroke No Light 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 PM Sukiyaki 4 Runner Cain's Blood 4 Runner Ripples 4Him Basics Of Life 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 cent pimp 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Wanksta 5th Dimension Aquarius 5th Dimension Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 5th Dimension One Less Bell To Answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up And Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 69 Boyz Tootie Roll 702 Get It Together 702 Steelo 702 Where My -

Those Who Seek and Have the Long to Ings

re ad ‘ I beg you all who this book to be gene rous in your criticism for I wrote it purely and solely wi th love and help for those who have had like experiences and for those who seek and have the long to ings . find love , wisdom and I peace as have wished to have . I have had the experience that there v is a world of lo e , where hate , jealousy and selfishness cannot come . Due to my material instruction on science of numbers , combined fi ve with my spiritual instruction , I write you the story of the higher and lower self as the invisible forces taught it to me for the pu r oi pose guiding me , giving me many experiences , helping me over f severe suf erings , encouraging me to observe , test and prove their teachings . I dedicate this book to th e truth seekers and to the unseen powers who have lighted my path . six The reason for writing this book is due to the encouragement from both the visible and invisible influences . My invisible helpers W ere those of the great beyond , those who passed over into the spirit land , also the forces of na ture which the Theosophical books call nature spirits . O ff and on these have been th e only true friends I have known . There were times in my life , when I experienced the remark of severe ! Jesus the Christ who said , My servants are not of this world . I had these experiences when I was a mere child . -

Religious-Verses-And-Poems

A CLUSTER OF PRECIOUS MEMORIES A bud the Gardener gave us, A cluster of precious memories A pure and lovely child. Sprayed with a million tears He gave it to our keeping Wishing God had spared you If only for a few more years. To cherish undefiled; You left a special memory And just as it was opening And a sorrow too great to hold, To the glory of the day, To us who loved and lost you Down came the Heavenly Father Your memory will never grow old. Thanks for the years we had, And took our bud away. Thanks for the memories we shared. We only prayed that when you left us That you knew how much we cared. 1 2 AFTERGLOW A Heart of Gold I’d like the memory of me A heart of gold stopped beating to be a happy one. I’d like to leave an afterglow Working hands at rest of smiles when life is done. God broke our hearts to prove to us I’d like to leave an echo He only takes the best whispering softly down the ways, Leaves and flowers may wither Of happy times and laughing times The golden sun may set and bright and sunny days. I’d like the tears of those who grieve But the hearts that loved you dearly to dry before too long, Are the ones that won’t forget. And cherish those very special memories to which I belong. 4 3 ALL IS WELL A LIFE – WELL LIVED Death is nothing at all, I have only slipped away into the next room. -

AN ANALYSIS of the MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS of NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 a THESIS S

AN ANALYSIS OF THE MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS OF NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Dale Ganz Copyright JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH 2010 Abstract Nina Simone was a prominent jazz musician of the late 1950s and 60s. Beyond her fame as a jazz musician, Nina Simone reached even greater status as a civil rights activist. Her music spoke to the hearts of hundreds of thousands in the black community who were struggling to rise above their status as a second-class citizen. Simone’s powerful anthems were a reminder that change was going to come. Nina Simone’s musical interpretation and approach was very unique because of her background as a classical pianist. Nina’s untrained vocal chops were a perfect blend of rough growl and smooth straight-tone, which provided an unquestionable feeling of heartache to the songs in her repertoire. Simone also had a knack for word painting, and the emotional climax in her songs is absolutely stunning. Nina Simone did not have a typical jazz style. Critics often described her as a “jazz-and-something-else-singer.” She moved effortlessly through genres, including gospel, blues, jazz, folk, classical, and even European classical. Probably her biggest mark, however, was on the genre of protest songs. Simone was one of the most outspoken and influential musicians throughout the civil rights movement. Her music spoke to the hundreds of thousands of African American men and women fighting for their rights during the 1960s. -

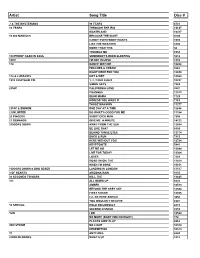

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Tourism in the Maldives : Experiencing the Difference from the Maldives Bénédicte Auvray

Tourism in the Maldives : experiencing the difference from the Maldives Bénédicte Auvray To cite this version: Bénédicte Auvray. Tourism in the Maldives : experiencing the difference from the Maldives. Tourism & Seductions of Difference, Sep 2010, Lisbonne, Portugal. halshs-00536400 HAL Id: halshs-00536400 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00536400 Submitted on 16 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Tourism in the Maldives: experiencing the difference from the Maldives Ms. Bénédicte AUVRAY PhD candidate Geography [email protected] University of Le Havre (Cirtai/UMR IDEES) +33 2 32 74 41 35 25, rue Philippe LEBON 76086 LE HAVRE Cedex France Abstract According to the official website of the Maldives Tourism Promotion Board, the country looks like a white and blue world for honeymooners, divers and budding Robinson Crusoe. Indeed it is the international representation of the Maldives. The reason for this touristic development is segregation: vacationers are allowed (and waited) to spend time in luxury resorts whereas Maldivian inhabitants are contained on local islands. In view of this phenomenon of social and spatial separation, the term “visit” is inappropriate. “Experience” would be more suitable: Maldivian island-hotel is a model of enclosure, repeated at different scales and concerning different people. -

Sandspur, Vol 93 No 03, October 15, 1986

University of Central Florida STARS The Rollins Sandspur Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 10-15-1986 Sandspur, Vol 93 No 03, October 15, 1986 Rollins College Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rollins Sandspur by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rollins College, "Sandspur, Vol 93 No 03, October 15, 1986" (1986). The Rollins Sandspur. 1644. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1644 vol. 93 (lolling SanctUfUiSi no. 3 \, QdoU*15, 1986 WIEWITH A FRIEND. dollinA, ScM&ipMfr managing editor margaret o'sullivan opinions editorials editor karen korn sports editor gregg kaye entertainment editor rick juergens news editor beth rapp MAKE IT COUNT MORE. art and graphics A Public Service Message from The National Association of Secretaries of kathi rhoads State, American Citizenship Education Project, (JOUKH This Newspaper & The Advertising Council business manager donna jean houge Resumes & Letters From $5 Manuscript Editing and Printing ABS PROFESSIONAL WRITING SERVICE contributors and staff 1st light west of Altamonte Mall steve appel on SR 436 at Hattaway • 260-6550 allison austin cathy collins rich conger scott crowe richard dickson mike garuckis andrea hobbs ONE-STOP tiffany hogan jonanthan lee jeff mc cormick lauren nagel COPY SHOP cesto pelota george pryor We copy, collate, bind, staple, fold, cut, tucker smith kristen svehla drill, and pad. -

Elisabeth Haich

Elisabeth Haich INITIATION AUTHOR'S NOTE It is far from my intentions to want to provide a historical picture of Egypt. A person who is living in any given place has not the faintest idea of the peculiarities of his country, and he does not consider customs, language and religion from an ethnographic point of view. He takes everything as a matter of course. He is a human being and has his joys and sorrows, just like every other human being, anywhere, any place, any time; for that which is truly human is timeless and changeless. My concern here is only with the human, not with ethnography and history. That is why I have, in relating the story which follows here, intentionally used modern terms. I have avoided using Egyptian sounding words to create the illusion of an Egyptian atmosphere. The teachings of the High Priest Ptahhotep are given in modern language so that modern people may understand them. For religious symbols also, I have chosen to use modern terms so that all may understand what these symbols mean. People of today understand us better if we say 'God' than if we were to use the Egyptian term 'Ptah' for the same concept. If we say 'Ptah' everyone immediately thinks, 'Oh yes, Ptah, the Egyptian God'. No! Ptah was not an Egyptian God. On the contrary, the Egyptians called the same God whom we call God, by the name of Ptah. And to take another example, their term for Satan was Seth. The words God and Satan carry meanings for us today which we would not get from the words Ptah or Seth. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 142 AUGUST 2ND, 2021 Is there a reader among us who doesn’t dig ZZ Top? We mourn the passing of Joseph Michael “Dusty” Hill (72), bassist, vocalist and keyboardist for the tres hombres. Blending blues, boogie, bone-crushing rock, born-for-MTV visuals, humor and outrageousness – they once took a passel of live animals on stage as part of their 1976 – 1977 Worldwide Texas Tour – Hill, drummer Frank Beard and guitarist Billy F. Gibbons have scorched stages worldwide. As a friend said, “it’s amazing how just three guys could make that much sound.” Rest in peace, Mr. Hill. In this issue: Anne E. Johnson gets inspired by the music of Renaissance composer William Byrd, and understands The Animals. Wayne Robins reviews Native Sons, the superb new album from Los Lobos. Ray Chelstowski interviews The Immediate Family, featuring studio legends Waddy Wachtel, Lee Sklar, Russ Kunkel and others, in an exclusive video interview. I offer up more confessions of a record collector. Tom Gibbs finds much to like in some new SACD discs. John Seetoo winds up his coverage of the Audio Engineering Society’s Spring 2021 AES show. Ken Sander travels through an alternate California reality. WL Woodward continues his series on troubadour Tom Waits. Russ Welton interviews cellist Jo Quail, who takes a unique approach to the instrument. In another article, he ponders what's needed for sustaining creativity. Adrian Wu looks at more of his favorite analog recordings. Cliff Chenfeld turns us on to some outstanding new music in his latest Be Here Now column. -

Ofir Touche Gafla Extracts from the Novel END's WORLD

1 | GAFLA Ofir Touche Gafla Extracts from the novel END'S WORLD 1. The End Some fifteen months after Marianne lost her life under bizarre aeronautical circumstances, her husband decided to celebrate her fortieth birthday. Their old friends, well aware of the couple’s love for one another, were not surprised to find, amid the daily monotony of their mail, an invitation to the home of the live husband and the late wife. They also knew that he had yet to have his final word on the matter, and that, beneath the emotional prattle and the love‐soaked murmurs, Ben Mendelssohn was a man of action. His friends, put at ease by the invitation, saw the party as classic Mendelssohn, which is to say a come‐as‐you‐are, be‐ready‐for‐ anything affair. After all, Ben paid the bills with his imagination, crafting surprise endings for a living. Writers of screenplays, writers at the dawn and dusk of their careers, letter writers, graphomaniacs, poets, drafters of Last Wills and Testaments—all used the services of Ben Mendelssohn, righter. In intellectual circles he was known as an epilogist; among laymen he remained anonymous, never once asking for his name to appear at the close of the work he sealed for others. Over time, experts were able to recognize his signature touches and, within their own literati circles, to admit to his genius. Marianne, who recognized his talent from the start, had a keen distaste for her husband’s enduring anonymity, but he, chuckling, would ask, “Do you know any famous tow‐truck drivers? All I do is drag miserable writers out of the mud.” After his wife’s funeral, Ben asked his friends to let him be. -

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - Updated April 9, 2006

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - updated April 9, 2006 compiled by Linda Bangert Please send any additions or corrections to Linda Bangert ([email protected]) and notice of any broken links to Neil Ottenstein ([email protected]). This listing of tour dates, set lists, opening acts, additional musicians was derived from many sources, as noted on each file. Of particular help were "Higher and Higher" magazine and their website at www.moodies- magazine.com and the Moody Blues Official Fan Club (OFC) Newsletters. For a complete listing of people who contributed, click here. Particular thanks go to Neil Ottenstein, who hosts these pages, and to Bob Hardy, who helped me get these pages converted to html. One-off live performances, either of the band as a whole or of individual members, are not included in this listing, but generally can be found in the Moody Blues FAQ in Section 8.7 - What guest appearances have the band members made on albums, television, concerts, music videos or print media? under the sub-headings of "Visual Appearances" or "Charity Appearances". The current version of the FAQ can be found at www.toadmail.com/~notten/FAQ-TOC.htm I've construed "additional musicians" to be those who played on stage in addition to the members of the Moody Blues. Although Patrick Moraz was legally determined to be a contract player, and not a member of the Moody Blues, I have omitted him from the listing of additional musicians for brevity. Moraz toured with the Moody Blues from 1978 through 1990. From 1965-1966 The Moody Blues were Denny Laine, Clint Warwick, Mike Pinder, Ray Thomas and Graeme Edge, although Warwick left the band sometime in 1966 and was briefly replaced with Rod Clarke.