PERSONAL STATEMENT Valerie Dean O'loughlin, Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macomb Community College Respiratory Therapy Articulation

Respiratory Therapy Bachelor of Science Degree Macomb Community College (MCC) Articulation Agreement and Transfer Guide This agreement offers students of Macomb Community College the opportunity to complete a bachelor’s degree in Respiratory Therapy after obtaining the National Board for Respiratory Care (NBRC) Registered Respiratory Therapist (RRT) credential. This program will provide graduates of an entry into respiratory care professional practice degree program with additional knowledge, skills, and attributes in leadership, management, education, research, or advanced clinical practice both to meet their current professional goals and to prepare them for practice as advanced degree respiratory therapists. The program is provisionally accredited by the Commission on Accreditation for Respiratory Care (CoARC) #510005. Communication Competency Requirements FSU Course FSU Course Title FSU Cr. Hrs. MCC Equiv. MCC Course Title MCC Cr. Hrs. COMM 105 or Interpersonal Communication or 3 *SPCH 2100 or Interpersonal Communication or 3 COMM 121 or Fundamentals of Public Speaking SPCH 1060 or Speech Communication or COMM 221 or Small Group Decision Making SPCH 1200 Group Discussion / Leadership or or or or COMM 251 Argumentation & Debate SPCH 2550 Argumentation & Debate ENGL 150 English 1 3 **ENGL 1180 or Communications 1 or 4 or ENGL 1210 Composition 1 3 ENGL 250 English 2 3 *ENGL 1190 or Communications 2 or 4 or ENGL 1220 Composition 2 3 Quantitative Literacy Requirements FSU Course FSU Course Title FSU Cr. Hrs. MCC Equiv. MCC Course Title MCC Cr. Hrs. MATH 115 Intermediate Algebra or ACT 24, 3 *MATH 1000 Intermediate Algebra 4 or SAT 580 or or or or MATH 117 Contemporary Mathematics or 4 MATH 1100 Everyday Mathematics ACT 24 or SAT 580 Natural Sciences Competency Requirements - 1 course with lab FSU Course FSU Course Title FSU Cr. -

Program Review

12/4/2019 https://programreviewblob.blob.core.windows.net/programreviewblob-prod/review-report-a82c59bc-c908-459e-9ceb-fa13bb663d58.html Welcome to Program Revie w 1 College of Alameda - 2019 BIOL - Instruction Program Review Program Overview Please verify the mission statement for your program. If your program has not created a mission statement, provide details on how your program supports and contributes to the College mission. We strive to provide a learning environment that values diversity, intellectual discussion, crical thinking, and problem-solving. We provide students the opportunity to explore the science of life. We are commied to excellence in our teaching, and help students acquire a knowledge of basic facts and theories in biology. Biology Department offers an Associate degree and is commied to teaching our students a history of scienfic discovery in biology, science concepts and how to test biological hypotheses. Students should appreciate the hierarchical nature of biological complexity and the importance of biological knowledge for solving societal problems through crical thinking. The courses in our department empower students to enhance their intellectual competence to achieve personal and professional goals. Program Total Faculty and/or Staff Full Time Part Time Reza Majlesi Leslie Bach Leslie Reiman Scott Shultz Peter Niloufari Vaishali Bhagwat Karen Wedaman Constanze Weyhenmeyer Muwafaqu Alasad Blank The Program Goals below are from your most recent Program Review or APU. If none are listed, please add your most recent program goals. Then, indicate the status of this goal, and which College and District goal your program goal aligns to. If your goal has been completed, please answer the follow up queson regarding how you measured the achievement of this goal. -

Thèse Et Mémoire

Université de Montréal Survivance 101 : Community ou l’art de traverser la mutation du paysage télévisuel contemporain Par Frédérique Khazoom Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques, Université de Montréal, Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de Maîtrise ès arts en Maîtrise en cinéma, option Cheminement international Décembre 2019 © Frédérique Khazoom, 2019 Université de Montréal Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Ce mémoire intitulé Survivance 101 : Community ou l’art de traverser la mutation du paysage télévisuel contemporain Présenté par Frédérique Khazoom A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes Zaira Zarza Président-rapporteur Marta Boni Directeur de recherche Stéfany Boisvert Membre du jury Résumé Lors des années 2000, le paysage télévisuel américain a été profondément bouleversé par l’arrivée d’Internet. Que ce soit dans sa production, sa création ou sa réception, l’évolution rapide des technologies numériques et l’apparition des nouveaux médias ont contraint l’industrie télévisuelle à changer, parfois contre son gré. C’est le cas de la chaîne généraliste américaine NBC, pour qui cette période de transition a été particulièrement difficile à traverser. Au cœur de ce moment charnière dans l’histoire de la télévision aux États-Unis, la sitcom Community (NBC, 2009- 2014; Yahoo!Screen, 2015) incarne et témoigne bien de différentes transformations amenées par cette convergence entre Internet et la télévision et des conséquences de cette dernière dans l’industrie télévisuelle. L’observation du parcours tumultueux de la comédie de situation ayant débuté sur les ondes de NBC dans le cadre de sa programmation Must-See TV, entre 2009 et 2014, avant de se terminer sur le service par contournement Yahoo! Screen, en 2015, permet de constater que Community est un objet télévisuel qui a constamment cherché à s’adapter à un média en pleine mutation. -

Download the Academic Plan

Page 1 of 5 WEST KENTUCKY COMMUNITY AND TECHNICAL COLLEGE HEALTH SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY Health Science Technology Associate in Applied Science Academic Plan Code 5100007019 Contact Information: Melissa Burgess [email protected] 270-534-3495 Student Name ID# Course Hours Grade Semester GENERAL EDUCATION MAT 110 Applied Math** OR 3 MAT 150 College Algebra and Functions (3) ENG 101 Writing I 3 FYE 105 First Year Experience 3 BIO 135 Basic Human Anatomy/Physiology with Lab** OR 4 BIO 137 Human Anatomy and Physiology I AND (4) BIO 139 Human Anatomy and Physiology II (4) PSY 110 General Psychology 3 Social/Behavioral Sciences 3 Heritage/Humanities 3 Oral Communications 3 Subtotal 25-29 REQUIRED TECHNICAL AND CERTIFICATE COURSES CLA 131 Medical Terminology from Greek and Latin OR 3 AHS 115 Medical Terminology OR (3) MIT 103 Medical Office Terminology (3) NAA 100 Nursing Assistant Skills I** 3 Digital Literacy* 0-3 Health Science Technical Courses (See below and next pages for a listing of applicable technical courses) 29-30 Subtotal 35-39 TOTAL 60-68 Students may take the following courses to meet the required 60 credit hours needed for the Health Science Technology degree: AHS 100, AHS 105, AHS 115, AHS 201, AHS 203, BAS 120, BIO 137, BIO 139, BIO 225 CIT 105, COM 181, COM 252, EFM 100, HST 101, HST 102, HST 103, HST 104, HST 121, HST 122, HST 123, NAA 102, OST 110, PHY 152, PHY 171, PHY 172, PLW 130, PLW 135, PLW 140, TEC 200, WPP 200 *Digital Literacy must be demonstrated by competency exam or successfully completing a digital literacy course. -

Interdisciplinary and Other 1

Interdisciplinary and Other 1 BMS 404. Human Physiology. 3 credits. SP INTERDISCIPLINARY AND Designed to provide pharmacy and pre-alllied health students with knowledge of human physiology. The function of the major organ OTHER systems is covered in a series of lectures and discussions. P: Registered Pharmacy Doctoral Program. Interdisciplinary and courses from the health science schools may be BMS 497. Directed Independent Research. 1-3 credits. OD available for College of Arts and Sciences students to take. This course consists of original scientific investigation under supervision CAS 101. Dean's Fellows Foundational Sequence. 0 credits. and guidance of the instructor. Upon successful completion of this Deans Fellows course. Graded Satisfactory/Unsatisfactory. P: Deans course, students will acquire the skills necessary to perform experiments, Fellow; IC. assess, and interpret results; demonstrate competence in the laboratory, effectively analyze, synthesize, and interpret data; and communicate their CAS 111. Introduction to Undergraduate Research. 1 credit. results. P: IC. This course is for first year students interested in learning about opportunities in undergraduate research and creative scholarly work IDC 401. Service Learning in Local Communities - Sports and Education. at Creighton. You will be introduced to specific research projects and 3 credits. develop the tools you need to pursue a faculty-led scholarly project. This This course combines service learning in a local community and in a course will provide an overview of specific skills, across disciplines, in the foreign country in order to compare experiences of the relationship areas of development of research questions, literature searches, research between sports, education, and development across different cultures. -

AA in Liberal Arts – BA in Political Science

2+2 Agreement: AA Liberal Arts at Nashua Community College and BA Political Science at Plymouth State University Years 1 and 2 at Nashua Community College Course ID Course Title Credits Year One at Nashua Community College BCPN 101 Computer Technology and Applications 3 ENGN 101 College Composition 4 ENGN xxx Literature Elective 3 ENGN 105,215,230,231,240,241 General Education: Group A-G Elective 3 POLN 102 Amer Gov't/Politics [D] General Education: Group C Elective 3 General Education: Group D Elective 3 General Education: Group E Elective 4 MTHN 106 Statistics I General Education: Group E Elective 3-4 (not MTHN 103) General Education: Group F or G Elective 3 Open Elective 3-4 Sub-total Credits for Year One at NCC 32-34 Year Two at Nashua Community College General Education: Group A-G Elective 3 POLN 101 Intro Political Science [D] General Education: Group A-G Elective 3-4 General Education: Group A-G Elective 3-4 General Education: Group B Elective 4 General Education: Group B Elective 4 General Education: Group C or D Elective 3 General Education: Group F or G Elective 3 Foreign Language General Education: Group F or G Elective 3 Foreign Language Open Elective 3 [CHWN 101, EDUN 103] Open Elective 3-4 Open Elective (as needed) 3-4 Sub-total Credits for Year Two at NCC 32-34 Minimum Credits at NCC for AA Liberal Arts 64 Years 3 and 4 at PSU Course ID Course Title Credits Year Three at PSU PO 2020 Public Administration (DICO) 3 PO 3120 Political Parties,Elections,Interest Groups 3 Technology Connection PO 3660 Political Analysis 3 PO -

Biology & Biotechology

Biology & Biotechology Degree: A.S. - Biotechnology Area: Science and Engineering Certificate: Biotechnology Dean: Michael Kane Phone: (916) 484-8107 Counseling: (916) 484-8572 Biotechnology Degree testing, and diagnostic work. Potential employers include biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, as well as laboratories in hospitals, This program provides the theory and skills necessary for entry into the government, and universities. biotechnology field, which uses cellular and molecular processes for industry or research. Course work includes practical laboratory skills with Requirements for Certificate 32-33 units emphasis on good laboratory practice, quality control, and regulatory issues in the biotechnology workplace. Completion of the program BIOL 310 General Biology (4) 4 - 5 or BIOL 400 Principles of Biology (5) also prepares the student for transfer at the upper division level to BIOL 440 General Microbiology 4 academic programs involving biotechnology. BIOT 300 Introduction to Biotechnology 4 Career Opportunities BIOT 315 Methods in Biotechnology 5 CHEM 305 Introduction to Chemistry (5) 5 This program prepares the student for entry-level work in the bioscience or CHEM 400 General Chemistry (5) industry in the areas of research and development, production, clinical CISC 300 Computer Familiarization 1 testing, and diagnostic work. Potential employers include biotechnology ENGWR 300 College Composition 3 and pharmaceutical companies, as well as laboratories in hospitals, MATH 120 Intermediate Algebra 5 government, and universities. -

2019-2020 Catalog Addendum December 2019

Fresno City College 2019-2020 Catalog Addendum December 2019 Table of Contents Certificate and Degree Requirements ................................................................................... 1 Transfer Requirements.......................................................................................................... 2 Special Areas of Study .......................................................................................................... 4 Associate Degree and Certificate Programs.......................................................................... 6 Courses Descriptions .......................................................................................................... 48 1101 East University Avenue, Fresno, California 93741 (559) 442-4600 www.fresnocitycollege.edu 1 CERTIFICATE AND DEGREE REQUIREMENTS Changes to Pages 35-39 Requirements for AA and AS Degrees Change: add ART 40 Area C: Humanities effective Fall 2019 ART 70 Area C: Humanities effective Fall 2019 ENGR 5 Computer Familiarity effective Fall 2019 PHIL 3A Area C: Humanities effective Fall 2019 PHIL 3B Area C: Humanities effective Fall 2019 Fresno City College 2019-2020 Catalog Addendum 2 TRANSFER INFORMATION AND REQUIREMENTS Changes to Pages 40-57 Course Identification Numbering Systems (C-ID) C-ID Number Fresno City College Course Change: add CHEM 101 CHEM 3A, Introductory General Chemistry CHEM 110 CHEM 1A, General Chemistry ENGR 180 ENGR 1A, Elementary Plane Surveying 1 HIT 100X HIT 1, Introduction to Health Information Management HIT 102X -

Bucks County Community College

As of: December 4, 2020 at 11:40 AM. Page 1 of 33 School: Bucks County Community College KU Transfer Equivalencies Subject: ACC Bucks County Community College External Course(s) Taken Date Range KU Equivalent Course(s) Credits ACC 280 COOPERATIVE EDUCATION- ACC from Jan 1900 through Today BUS 880 3 Subject: ACCT Bucks County Community College External Course(s) Taken Date Range KU Equivalent Course(s) Credits ACCT 090 INTRODUCTORY ACCOUNTING from Jan 1997 through Today Does not Transfer ACCT 100 PRINCIPLES ACCOUNTING I from Jan 1997 through Today ACC 121 4 ACCT 101 PRINCIPLES ACCOUNTING II from Jan 1997 through Today ACC 122 4 ACCT 103 INTRO ACCOUNTING from Jan 2004 through Today ACC 121 3 ACCT 105 PRIN OF ACCOUNTING I from Jan 2005 through Aug 2012 ACC 121 4 ACCT 105 FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING from Aug 2012 through Today ACC 121 4 ACCT 106 PRIN OF ACCOUNTING II from Jan 2005 through Aug 2012 ACC 122 4 ACCT 106 MANAGERIAL ACCOUNTING from Aug 2012 through Today ACC 122 4 ACCT 110 PER & FINANCIAL PLANNING from Jan 1997 through Aug 2018 ACC 880 3 ACCT 110 PER & FINANCIAL PLANNING from Aug 2018 through Today PRO 185 3 ACCT 120 PAYROLL RECORDS & PLAN from Jan 1997 through Jan 2019 ACC 880 3 ACCT 120 PAYROLL RECORDS & PLAN from Jan 2019 through Today BUS 880 3 ACCT 130 ACCT APPL FOR MICROCOMP from Jan 1997 through Jan 2019 ACC 880 3 ACCT 130 ACCT APPL FOR MICROCOMP from Jan 2019 through Today BUS 880 3 ACCT 200 INTERMEDIATE ACCOUNTING I from Jan 2004 through Today ACC 321 3 ACCT 201 INTERMEDIATE ACCOUNTINGII from Jan 1997 through Jan 2019 ACC 880 -

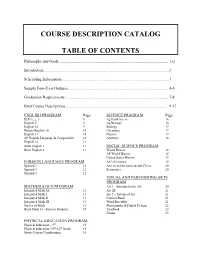

Course Description Catalog Table of Contents

COURSE DESCRIPTION CATALOG TABLE OF CONTENTS Philosophy and Goals .................................................................................................... 1-2 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................3 Scheduling Information .............................................................................................................3 Sample Four-Year Outlines .......................................................................................................4-6 Graduation Requirements ......................................................................................................... 7-8 Brief Course Descriptions ....................................................................................................... 9-37 ENGLISH PROGRAM Page SCIENCE PROGRAM Page ELD 1, 2, 3 9 Ag Earth Science 16 English 9 9 Ag Biology 16 English 10 9 Biology 17 Honors English 10 10 Chemistry 17 English 11 10 Physics 17 AP English Language & Composition 10 Anatomy 18 English 12 11 Butte English 2 11 SOCIAL SCIENCE PROGRAM Butte English 4 11 World History 18 AP World History 18 United States History 19 FOREIGN LANGUAGE PROGRAM AP US History 19 Spanish 1 12 American Government and Civics 20 Spanish 2 12 Economics 20 Spanish 3 12 VISUAL AND PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAM MATHEMATICS PROGRAM Art 1 – Introduction to Art 20 Integrated Math IA 13 Art 1B 21 Integrated Math I 13 Art 2 – Advanced Art 21 Integrated Math II 13 Concert Band 21 Integrated Math -

Interdisciplinary Degree Program in Science 1

Interdisciplinary Degree Program in Science 1 BIOL 151. Introduction to Biological Sciences I. 3 Hours. INTERDISCIPLINARY DEGREE Semester course; 3 lecture hours. 3 credits. Prerequisites: MATH 141, MATH 151, MATH 200, MATH 201 or a satisfactory score on the math PROGRAM IN SCIENCE placement exam; and CHEM 100 with a minimum grade of B, CHEM 101 with a minimum grade of C or a satisfactory score on the chemistry Charlene D. Crawley, Ph.D. placement exam. Introduction to core biological concepts including Coordinator cell structure, cellular metabolism, cell division, DNA replication, gene expression and genetics. Designed for biology majors. has.vcu.edu/science (http://www.has.vcu.edu/science/) BIOL 152. Introduction to Biological Sciences II. 3 Hours. The interdisciplinary program in science provides students with a Semester course; 3 lecture hours. 3 credits. Prerequisites: BIOL 151 and broad, yet fundamental, grounding in the sciences. In addition to the CHEM 101, both with a minimum grade of C. Focuses on evolutionary spectrum of required mathematics and science courses, students select principles, the role of natural selection in the evolution of life forms, a concentration from biology, chemistry, physics or professional science. taxonomy and phylogenies, biological diversity in the context of form and function of organisms, and and basic principles of ecology. Designed for Students completing this curriculum earn a Bachelor of Science in biology majors. Science. BIOL 200. Quantitative Biology. 3 Hours. For information concerning the program and advising, students should Semester course; 3 lecture hours (delivered online or hybrid). 3 credits. contact the program coordinator or their academic adviser. -

Lassen Community College Course Outline HO 70 Medical Assisting

Lassen Community College Course Outline HO 70 Medical Assisting: Core 7.0 Units I. Catalog Description This course is designed to provide entry level skills training required for the profession of medical assisting. The course covers core components required for advancement in both the administration and clinical medical assisting certificate program. Students must complete all course hours and must achieve a 75% on their final class grade and must achieve a final exam grade of 75% or better to be eligible to advance to the next course in the series. Uniform and lab fee of $200 will be collected at registration. This course has been approved for hybrid and online delivery. Recommended Preparation: Successful completion of ENGL105 or equivalent assessment placement. After registering for the Medical Assisting Program the student will: 1. Verify possession of a valid BLS CPR card from ASHI, AHA. 2. Verify that he or she doesn’t have a criminal record and can work in a health care setting. 3. Provide documentation of recent two step tuberculosis testing or equivalent 4. Provide records of vaccinations or titers required for entry in to clinical environments. 5. Comply with testing required for clinical site rotations such as Covid-19 testing. 6. Complete a 10 panel drug screening. 7. Complete a physical exam. 8. Create an account in My Clinical Exchange and complete all competencies. Does not transfer to UC/CSU 125 Hours Lecture Scheduled: Summer II. Coding Information Repeatability: Not Repeatable, Take 1 Time Grading Option: Graded or Credit/No Credit Credit Type: Credit - Degree Applicable TOP Code: 120820 III.