Chapter Four

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vespers on the World Day of Prayer for the Care of Creation

N. 160902a Friday 02.09.2016 Vespers on the World Day of Prayer for the Care of Creation Yesterday afternoon, in St. Peter’s Basilica, Pope Francis presided at the celebration of vespers on the occasion of the World Day of Prayer for the Care of Creation. The homily was pronounced by the Preacher to the Papal Household, Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa, O.F.M. Cap., who emphasised that the sovereignty of human beings over the cosmos is not a triumphalism of the species but rather the assumption of responsibility for the weak, the poor and the helpless. “The God of the Bible, but also of other religions, is a God Who hears the cry of the poor … who disdains nothing He created”. “The Incarnation of the Word brought another reason to take care of the weak and the poor, whatever race or religion he may belong to. Indeed, this does not say merely that “God was made man”, but also that man was made God: that is, what type of man He chose to be: not rich or powerful, but poor, weak and helpless. … The form of the incarnation is no less important than the fact”. “This was the step further that Francis of Assisi, with his experience of life, was able to give to theology. … The Saint was moved to tears by the Nativity by … the humility and the poverty of the Son of God Who, ‘though He was rich, yet for your sake He became poor’. In him, love for poverty and love for creation went hand in hand, and had a common root in his radical renouncement of the will to possess”, explained Fr. -

A. Brief Overview of the Administrative History of the Holy See

A. Brief Overview of the Administrative History of the Holy See The historical documentation generated by the Holy See over the course of its history constitutes one of the most important sources for research on the history of Christianity, the history of the evolution of the modern state, the history of Western culture and institutions, the history of exploration and colonization, and much more. Though important, it has been difficult to grasp the extent of this documentation. This guide represents the first attempt to describe in a single work the totality of historical documentation that might properly be considered Vatican archives. Although there are Vatican archival records in a number of repositories that have been included in this publication, this guide is designed primarily to provide useful information to English-speaking scholars who have an interest in using that portion of the papal archives housed in the Vatican Archives or Archivio Segreto Vaticano (ASV). As explained more fully below, it the result of a project conducted by archivists and historians affiliated with the University of Michigan. The project, initiated at the request of the prefect of the ASV, focused on using modem computer database technology to present information in a standardized format on surviving documentation generated by the Holy See. This documentation is housed principally in the ASV but is also found in a variety of other repositories. This guide is, in essence, the final report of the results of this project. What follows is a complete printout of the database that was constructed. The database structure used in compiling the information was predicated on principles that form the basis for the organization of the archives of most modem state bureaucracies (e.g., provenance). -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC CONSTITUTION PASTOR BONUS JOHN PAUL, BISHOP SERVANT OF THE SERVANTS OF GOD FOR AN EVERLASTING MEMORIAL TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction I GENERAL NORMS Notion of Roman Curia (art. 1) Structure of the Dicasteries (arts. 2-10) Procedure (arts. 11-21) Meetings of Cardinals (arts. 22-23) Council of Cardinals for the Study of Organizational and Economic Questions of the Apostolic See (arts. 24-25) Relations with Particular Churches (arts. 26-27) Ad limina Visits (arts. 28-32) Pastoral Character of the Activity of the Roman Curia (arts. 33-35) Central Labour Office (art. 36) Regulations (arts. 37-38) II SECRETARIAT OF STATE (Arts. 39-47) 2 First Section (arts. 41-44) Second Section (arts. 45-47) III CONGREGATIONS Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (arts. 48-55) Congregation for the Oriental Churches (arts. 56-61) Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments (arts. 62-70) Congregation for the Causes of Saints (arts. 71-74) Congregation for Bishops (arts. 75-84) Pontifical Commission for Latin America (arts. 83-84) Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (arts. 85-92) Congregation for the Clergy (arts. 93-104) Pontifical Commission Preserving the Patrimony of Art and History (arts. 99-104) Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and for Societies of Apostolic Life (arts. 105-111) Congregation of Seminaries and Educational Institutions (arts. 112-116) IV TRIBUNALS Apostolic Penitentiary (arts. 117-120) Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura (arts. 121-125) Tribunal of the Roman Rota (arts. 126-130) V PONTIFICAL COUNCILS Pontifical Council for the Laity (arts. -

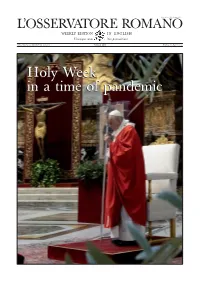

Holy Week in a Time of Pandemic

Price € 1,00. Back issues € 2,00 L’O S S E RVATOR E ROMANO WEEKLY EDITION IN ENGLISH Unicuique suum Non praevalebunt Fifty-third year, number 15 (2.642) Vatican City Friday, 10 April 2020 HolyHoly WeekWeek inin aa timetime ofof pandemicpandemic page 2 L’OSSERVATORE ROMANO Friday, 10 April 2020, number 15 The Holy Father appointed Fr Krzysztof Chudzio as Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of Przemyśl for Latins, Poland, assign- VAT I C A N ing him the titular episcopal See of Marazanae. Until now he has served The Holy Father appointed Fr Mi- as parish priest of Jasienica Rosielna BULLETIN chael G. McGovern as Bishop of (3 Apr.). Belleville. Until now he has served as episcopal vicar ad interim of Vi- Bishop-elect Chudzio, 56, was AUDIENCES ing the seminary he studied electric- cariate I, vicar forane of the Deneary born in Przemyśl, Poland. He was al studies. He holds a degree in I-C and parish priest of the Saint ordained a priest on 14 June 1988. Saturday, 4 April philosophy and theology. He was or- Raphael the Archangel Parish in dained a priest on 18 December The Holy Father appointed Fr Fran- Cardinal Marc Ouellet, PSS, Prefect Old Mill Creek (3 Apr.). 1989. cisco Castro Lalupú as titular Bish- of the Congregation for Bishops Bishop-elect McGovern, 55, was op of Putia in Byzacena and Auxili- Cardinal Luis Antonio G. Tagle, The Holy Father accepted the resig- born in Chicago, USA . He holds a ary Bishop of the Archdiocese of Prefect of the Congregation for the nation of Bishop Edward K. -

Pope's Preacher Goes Back to Basics in Talks to Bishops

Pope's preacher goes back to basics in talks to bishops https://www.ncronline.org/print/news/accountability/popes-preacher-goe... Published on National Catholic Reporter ( https://www.ncronline.org ) Jan 11, 2019 Home > Pope's preacher goes back to basics in talks to bishops Pope's preacher goes back to basics in talks to bishops by Tom Roberts Editor's note: The texts of the talks delivered by Capuchin Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa, preacher of the papal household, to the U.S. bishops during their Jan. 2-8 retreat at Mundelein Seminary, outside of Chicago, are available at this link. Texts of the 11 talks delivered to the U.S. bishops who gathered for a week's retreat at Mundelein Seminary outside of Chicago show a heavy emphasis on traditional themes, a robust defense of celibacy, a severe criticism of attachment to money and an endorsement of new lay movements as a replacement for declining numbers of clerics. Capuchin Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa, the official NCR obtained the texts, 84 single-spaced pages, and preacher of the papal household, delivers the homily they can be seen in their entirety here. They were delivered to U.S. bishops during Mass Jan. 3 in the Chapel of during the Jan. 2-8 retreat by Capuchin Fr. Raniero the Immaculate Conception at Mundelein Seminary Cantalamessa, preacher of the papal household. during the bishops' Jan. 2-8 retreat at the University of St. Mary of the Lake in Illinois, near Chicago. The talks contain only passing reference to the sex abuse (CNS/Bob Roller) scandal that was the reason behind the unusual retreat, suggested by Pope Francis, and the omission was intentional. -

Papal Transitions

Backgrounder Papal Transition 2013 prepared by Office of Media Relations United States Conference of Catholic Bishops 3211 Fourth Street NE ∙ Washington, DC 20017 202-541-3200 ∙ 202-541-3173 fax ∙ www.usccb.org/comm Papal Transitions Does the Church have a formal name for the transition period from one pope to another? Yes, in fact, this period is referred to by two names. Sede vacante, in the Church’s official Latin, is translated "vacant see," meaning that the see (or diocese) of Rome is without a bishop. In the 20th century this transition averaged just 17 days. It is also referred to as the Interregnum, a reference to the days when popes were also temporal monarchs who reigned over vast territories. This situation has almost always been created by the death of a pope, but it may also be created by resignation. When were the most recent papal transitions? On April 2, 2005, Pope John Paul II died at the age of 84 after 26 years as pope. On April 19, 2005, German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, formerly prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, was elected to succeed John Paul II. He took the name Pope Benedict XVI. There were two in 1978. On August 6, 1978, Pope Paul VI died at the age of 80 after 15 years as pope. His successor, Pope John Paul I, was elected 20 days later to serve only 34 days. He died very unexpectedly on September 28, 1978, shocking the world and calling the cardinals back to Rome for the second time in as many months. -

The Formal Blazon Texts for Bishop O'connell

THE FORMAL BLAZON OF THE EPISCOPAL COAT OF ARMS OF DAVID GERARD O’CONNELL D.D. TITULAR BISHOP OF CELL AUSAILLE AUXILIARY TO THE METROPOLITAN OF LOS ANGELES TIERCED IN PAIRLE ARGENT, VERT AND AZURE. IN CHIEF A ROSE GULES BARBED AND SEEDED OR AND IN DEXTER BASE A REPRESENTATION OF THE LAMB OF GOD ARGENT, NIMBED, ARMED AND SUPPORTING ON ITS SHOULDER A CROSSED STAFF OR. IN SINISTER BASE A STAG TRIPPANT PROPER ARMED OR. ON A CHIEF ENARCHED AZURE A FLEUR-DE-LIS OR BETWEEN TWO WINGS DISPLAYED AND INVERRTED ARGENT. AND FOR A MOTTO « JESUS I TRUST IN YOU » THE OFFICE OF AUXILIARY BISHOP The Office of Auxiliary, or Assistant, Bishop came into the Church around the sixth century. Before that time, only one bishop served within an ecclesial province as sole spiritual leader of that region. Those clerics who hold this dignity are properly entitled “Titular Bishops” whom the Holy See has simultaneously assigned to assist a local Ordinary in the exercise of his episcopal responsibilities. The term ‘Auxiliary’ refers to the supporting role that the titular bishop provides a residential bishop but in every way, auxiliaries embody the fullness of the episcopal dignity. Although the Church considers both Linus and Cletus to be the first auxiliary bishops, as Assistants to St. Peter in the See of Rome, the first mention of the actual term “auxiliary bishop” was made in a decree by Pope Leo X (1513‐1521) entitled de Cardinalibus Lateranses (sess. IX). In this decree, Leo confirms the need for clerics who enjoy the fullness of Holy Orders to assist the Cardinal‐Bishops of the Suburbicarian Sees of Ostia, Velletri‐Segni, Sabina‐Poggia‐ Mirteto, Albano, Palestrina, Porto‐Santo Rufina, and Frascati, all of which surround the Roman Diocese. -

History of the Christian Church, Volume VI: the Middle Ages

History of the Christian Church, Volume VI: The Middle Ages. A.D. 1294-1517 Author(s): Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian CLassics Ethereal Library Description: Philip Schaff©s History of the Christian Church excels at providing an impressive and instructive historical treatment of the Christian church. This eight volume work begins with the early Church and ends at 1605 with the Swiss Reforma- tion. Schaff©s treatment is comprehensive and in depth, dis- cussing all the major (and minor!) figures, time periods, and movements of the Church. He includes many footnotes, maps, and charts; he even provides copies of original texts in his treatment. One feature of the History of the Christian Church that readers immediately notice is just how beautifully written it is--especially in comparison to other texts of a sim- ilar nature. Simply put, Schaff©s prose is lively and engaging. As one reader puts it, these volumes are "history written with heart and soul." Although at points the scholarship is slightly outdated, overall History of the Christian Church is great for historical referencing. Countless people have found History of the Christian Church useful. Whether for serious scholar- ship, sermon preparation, daily devotions, or simply edifying reading, History of the Christian Church comes highly recom- mended. Tim Perrine CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: Christianity History i Contents Title Page 1 Preface 2 History of the Christian Church, Volume VI 4 Introductory Survey 4 The Decline Of The Papacy And The Avignon Exile 7 Sources and Literature 8 Pope Boniface VIII. 1294-1303 13 Boniface VIII. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 06:48:52PM Via Free Access the POPE’S HOUSEHOLD and COURT in the EARLY MODERN AGE

THE EARLY MODERN WORLD Maria Antonietta Visceglia - 9789004206236 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 06:48:52PM via free access THE POPE’S HOUSEHOLD AND COURT IN THE EARLY MODERN AGE Maria Antonietta Visceglia Traditionally, the international historiography of the papal court in the Modern Age has concentrated on the origins and development of the curial bureaucracy,1 and on the relationship between this bureau- cracy and the Italian aristocracy. This practice was in line with the general debate about the rise of the modern state—of which the Eccle- siastical State could be considered an early, original model.2 Studies on the figure of the cardinal-nephew—the secretary of state3—and on pontifical diplomacy added a lively field of research still fitting into the above-mentioned debate.4 1 Peter Partner, The Pope’s Men: the Papal Civil Service in the Renaissance (Oxford 1990). 2 Paolo Prodi, Il sovrano pontefice. Un corpo e due anime: la monarchia papale nella prima età moderna (Bologna 1982) translated Susan Haskins, The Papal Prince, One Body and Two Souls: The Papal Monarchy in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge 1987). The bibliography on the themes of bureaucracy and Italian aristocracy of the papal state in the modern era is extensive. These research themes were established at the end of the 1990s with the reviews of Marco Pellegrini, ‘Corte di Roma e aris- tocrazie italiane in età moderna. Per una lettura storico-sociale della curia romana’, in: Rivista di storia e letteratura religiosa XXX (1994) pp. 543–602; Maria Antonietta Visceglia, ‘Burocrazia, mobilità sociale e patronage alla corte di Roma tra Cinque e Seicento. -

Pandemic Is a Reminder of Our Own Mortality, Papal Preacher Says

Pandemic is a reminder of our own mortality, papal preacher says The coronavirus is not some form of divine punishment but a tragic event that, like all suffering in one’s life, is used by God to awaken humanity, said the preacher of the papal household. “The coronavirus pandemic has abruptly roused us from the greatest danger individuals and humanity have always been susceptible to: the delusion of omnipotence,” Capuchin Rev. Raniero Cantalamessa said during an April 10 service commemorating Christ’s death on the cross. “It took merely the smallest and most formless element of nature, a virus, to remind us that we are mortal, that military power and technology are not sufficient to save us,” he said. Pope Francis presided over the Good Friday Liturgy of the Lord’s Passion at the Altar of the Chair in St. Peter’s Basilica, which was nearly empty and completely silent. After processing into the sacred edifice in silence, the 83-year-old pope, aided by two assistants, got down onto his knees and lay prostrate on the floor before the altar in a sign of adoration and penance. Hands clasped under him and eyes closed, the pope silently prayed before a crucifix draped in red. During the liturgy, the pope and a small congregation of nearly a dozen people stood as three deacons read the account of the Passion from the Gospel of St. John. As is customary, the papal household’s preacher gave the homily. Taking preventative measures into account, the pope was the only one who took part in venerating the cross. -

MEDIA GUIDE Apostolic Journey of Pope Francis to the United States of America September 22-27, 2015

MEDIA GUIDE Apostolic Journey of Pope Francis to the United States of America September 22-27, 2015 United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Washington, DC #PopeInUS #PapaEnUSA MEDIA GUIDE Apostolic Journey of Pope Francis to the United States of America September 22-27, 2015 United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Washington, DC #PopeInUS #PapaEnUSA Copyright © 2015, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Wash- ington, DC. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright holder. All information in this guide was accurate at the time of printing. Times are Eastern standard Time. For up-to-date information, please visit media.uspapalvisit.org. Note: All media with access inside the venues or secured areas must arrive at the sites with appropriate credentials. Security will not allow access unless you are accompanied by staff or the US Secret Service. Contents Background . 1 Pope Francis .................................. 3 U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops ............... 5 U.S. Cardinals ................................. 7 USCCB Staff ................................. 10 Selected Members of the Papal Entourage .......... 13 Others Involved in the Papal Visit ................ 14 Archdiocese of Washington ..................... 15 Archdiocese of New York ....................... 17 Archdiocese of Philadelphia ..................... 20 Schedule of Activities . 22 Tuesday, September 22—Washington, DC ......... 23 Wednesday, September 23—Washington, DC ....... 25 Thursday, September 24—Washington, DC ........ 30 Thursday, September 24—New York .............. 32 Friday, September 25—New York ................ 34 Saturday, September 26—Philadelphia ............ 37 Sunday, September 27—Philadelphia ............. 42 USCCB Subject Experts . -

Other Institutes of the Roman Curia - Advocates - Institutions Connected with the Holy See

The Holy See - Other Institutes of the Roman Curia - Advocates - Institutions connected with the Holy See VII OTHER INSTITUTES OF THE ROMAN CURIAPrefecture of the Papal HouseholdArt. 180 — The Prefecture of the Papal Household looks after the internal organization of the papal household, and supervises everything concerning the conduct and service of all clerics and laypersons who make up the papal chapel and family.Art. 181 — § 1. It is at the service of the Supreme Pontiff, both in the Apostolic Palace and when he travels in Rome or in Italy.§ 2. Apart from the strictly liturgical aspect, which is handled by the Office for the Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff, the Prefecture sees to the planning and carrying out of papal ceremonies and determines the order of precedence.§ 3. It arranges public and private audiences with the Pontiff, in consultation with the Secretariat of State whenever circumstances so demand and under its direction it arranges the procedures to be followed when the Roman Pontiff meets in a solemn audience with heads of State, ambassadors, members of governments, public authorities, and other distinguished persons.Office for the Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme PontiffArt. 182 — § 1. The Office for the Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff is to prepare all that is necessary for the liturgical and other sacred celebrations performed by the Supreme Pontiff or in his name and supervise them according to the current prescriptions of liturgical law.§ 2. The master of papal liturgical celebrations is appointed by the Supreme Pontiff to a five-year term of office; papal masters of ceremonies who assist him in sacred celebrations are likewise appointed by the secretary of state to a term of the same length.VIII ADVOCATES Art.