Post-COVID-19 Paediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 1003 Thursday, No. 6 28 January 2021 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) 28/01/2021A00100Covid-19 Vaccination Programme: Statements � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 565 28/01/2021N00100Ceisteanna ó Cheannairí - Leaders’ Questions � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 593 28/01/2021Q00500Ceisteanna ar Reachtaíocht a Gealladh - Questions on Promised Legislation � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 602 28/01/2021T01100Covid-19 (Social Protection): Statements � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 611 28/01/2021JJ00200Response of the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage to Covid-19: Statements � � � � � � 645 28/01/2021XX02400Ábhair Shaincheisteanna Tráthúla - Topical Issue Matters � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 683 28/01/2021XX02600Saincheisteanna Tráthúla - Topical Issue Debate � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 685 28/01/2021XX02700School Facilities � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 685 28/01/2021YY00400Post Office Network � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 687 28/01/2021AAA00150Architectural Heritage � � � � � � -

British Politics and Policy at LSE: How to Mitigate the Risk of Psychological Injury to COVID-19 Frontline Workers Page 1 of 2

British Politics and Policy at LSE: How to mitigate the risk of psychological injury to COVID-19 frontline workers Page 1 of 2 How to mitigate the risk of psychological injury to COVID-19 frontline workers Jennifer Brown and Yvonne Shell discuss the possibility of healthcare workers experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder and other similar conditions as a result of dealing with COVID-19. They write that the antidote includes clarity in chain of command, effective supplies of equipment, and good communication. A perfect storm is gathering for the experience of psychological consequences by frontline staff during this world health crisis. Essential for key workers’ mental health in the face of a disaster such as that presented by the COVID-19 pandemic is resilience. This is the lesson learnt by Doctors Without Borders – an international medical humanitarian organization – for the welfare of its staff working in disaster areas. Resilience is personal, organisational, family and community. Resilience happens in a context and is a shared experience. That’s why our ‘clap for carers’ on a Thursday evening may have such significance for frontline workers beyond the immediacy of expressed appreciation. We already know that medical staff, social and care workers as well as emergency personnel can suffer symptoms of stress in normal circumstances and may be especially vulnerable in extremis. It is widely accepted that those who undertake such roles may experience Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a condition we readily associate with veterans from war. PTSD occurs when a person is confronted by actual or threatened exposure to death or serious injury to themselves or others. -

The Incidence, Characteristics and Outcomes of Pregnant Women Hospitalized with Symptomatic And

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.04.21249195; this version posted January 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY 4.0 International license . 1 The incidence, characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women hospitalized with symptomatic and 2 asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in the UK from March to September 2020: a national cohort 3 study using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) 4 5 Covid-19 in pregnancy 6 7 Nicola Vousden1,2 PhD, Kathryn Bunch MA1, Edward Morris MD3, Nigel Simpson MBChB4, Christopher 8 Gale PhD5, Patrick O’Brien MBBCh6, Maria Quigley MSc1, Peter Brocklehurst MSc7 9 Jennifer J Kurinczuk MD1, Marian Knight DPhil1 10 11 1National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of 12 Oxford, UK 13 2School of Population Health & Environmental Sciences, King’s College London, UK 14 3Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, London, UK 15 4Department of Women's and Children's Health, School of Medicine, University of Leeds, UK 16 5Neonatal Medicine, School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, 17 UK 18 6Institute for Women’s Health, University College London, London, UK 19 7Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit, Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, UK 20 21 Corresponding author: 22 Marian Knight, National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Nuffield Department of Population Health, 23 University of Oxford, Old Rd Campus, Oxford, OX3 7LF, UK 24 Tel: 01865 289727 Email: [email protected] 25 26 Non-standard abbreviations: 27 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists - RCOG 28 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. -

Vaccinating the World in 2021

Vaccinating the World in 2021 TAMSIN BERRY DAVID BRITTO JILLIAN INFUSINO BRIANNA MILLER DR GABRIEL SEIDMAN DANIEL SLEAT EMILY STANGER-SFEILE MAY 2021 RYAN WAIN Contents Foreword 4 Executive Summary 6 Vaccinating the World in 2021: The Plan 8 Modelling 11 The Self-Interested Act of Vaccinating the World 13 Vaccinating the World: Progress Report 17 Part 1: Optimise Available Supply in 2021 19 Part 2: Reduce Shortfall by Boosting Vaccine Supply 22 The Short Term: Continue Manufacturing Medium- and Long-Term Manufacturing Part 3: Ensure Vaccine Supply Reaches People 37 Improving Absorption Capacity: A Blueprint Reducing Vaccine Hesitancy Financing Vaccine Rollout Part 4: Coordinate Distribution of Global Vaccine Supply 44 Conclusion 47 Endnotes 48 4 Vaccinating the World in 2021 Foreword We should have recognised the warning signs that humanity’s international response to Covid-19 could get bogged down in geopolitical crosscurrents. In early March 2020, a senior Chinese leader proclaimed in a published report that Covid-19 could be turned into an opportunity to increase dependency on China and the Chinese economy. The following month, due in part to the World Health Organisation’s refusal to include Taiwan in its decision- making body, the Trump administration suspended funding to the agency. In May 2020, President Trump announced plans to formally withdraw from it. Quite naturally, many public-health experts and policymakers were discouraged by the growing possibility that global politics could overshadow efforts to unite the world in the effort to fight the disease. However, this report from the Global Health Security Consortium offers hope. It recommends a strategic approach to “vaccine diplomacy” that can help the world bring the pandemic under control. -

Daily Report Friday, 19 February 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Friday, 19 February 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 19 February 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (03:32 P.M., 19 February 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 8 Ofgem 17 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Parental Leave 18 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 8 Paternity Leave 18 Additional Restrictions Grant: Post Office: Finance 19 Harlow 8 Post Office: Subsidies 19 Boilers 8 Renewable Energy 20 Business: Carbon Emissions 9 Small Businesses 21 Business: Coronavirus 10 UK Emissions Trading Coal: Cumbria 10 Scheme 21 Conditions of Employment: Warm Home Discount Coronavirus 11 Scheme: Coronavirus 22 Coronavirus: Vaccination 11 Weddings: Coronavirus 22 Delivery Services: Industrial CABINET OFFICE 23 Health and Safety 11 Cabinet Office: Public Employment 12 Appointments 23 Environment Protection 12 Coronavirus: Disease Control 24 Flexible Working 13 Government Departments: Fracking 13 Procurement 25 Government Assistance 14 Knives: Crime 25 Green Homes Grant Scheme 14 Travel: Coronavirus 25 Industrial Health and Safety: UK Relations with EU: Coronavirus 15 Parliamentary Scrutiny 26 Intellectual Property 15 Weddings: Coronavirus 26 Iron and Steel: Manufacturing CHURCH COMMISSIONERS 27 Industries 16 Church Commissioners: Local Restrictions Support Carbon Emissions 27 Grant 16 Church Schools: Coronavirus 28 Television Licences: Fees and Churches: -

The COVID-19 Pandemic's Evolving Impacts on the Labor Market

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 14108 The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Evolving Impacts on the Labor Market: Who’s Been Hurt and What We Should Do Brad J. Hershbein Harry J. Holzer FEBRUARY 2021 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 14108 The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Evolving Impacts on the Labor Market: Who’s Been Hurt and What We Should Do Brad J. Hershbein W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research and IZA Harry J. Holzer Georgetown University and IZA FEBRUARY 2021 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. -

Covid-19 Recovery Timeline (Government Announcements and the Council’S Response)

Covid-19 recovery timeline (Government announcements and the Council’s response) Key: Government announcements Rotherham response/decisions taken/activity Other Those highlighted are yet to take place. June 21st June (TBC, 21 June is earliest possible date) Step four of lockdown easing: all legal limits on social contact removed and reopening of final closed sectors of economy. May 17th May (TBC, 17 May is earliest possible date) Step three of lockdown easing: most outdoor social contact rules lifted, six people or two households can meet indoors and indoor hospitality and hotel can open. April 12th April (TBC, 12 April is earliest possible date) Step two of lockdown easing: non- essential retail and personal care can reopen, hospitality outdoors and indoor leisure can reopen. March 29th March Step one of lockdown easing to continue: six people or two households allowed to meet outdoors, outdoor sports facilities can reopen, organised sport allowed and the stay at home order will end (though people should stay local as much as possible). 27th March Hope Fields Covid-19 memorial to open to the public at Thrybergh Country Park. 8th March Step one of lockdown easing to begin: children to return to school, care homes to be allowed one regular indoor visitor and two people allowed to sit together outdoors. February 24th February Rescheduled Introduction to Mindfulness workshop held for staff. New £700m education recovery package laid out to help children and young people catch up on lost learning. 23rd February Following announcement of lockdown easing roadmap, the Council and its health partners called for residents to keep vigilant and get tested if needed. -

Covid Economics Vetted and Real-Time Papers

COVID ECONOMICS VETTED AND REAL-TIME PAPERS ISSUE 72 18 MARCH 2021 COUNTERCYCLICAL CAPITAL REQUIREMENTS Naz Koont and Stefan Walz MEASURING INFLATION GLOBAL PRODUCTION NETWORKS Alberto Cavallo Hongyong Zhang SHE-CESSION WHO’S BEEN HURT? Stefania Fabrizio, Diego B.P. Gomes and Brad J. Hershbein and Harry J. Holzer Marina M. Tavares Covid Economics Vetted and Real-Time Papers Covid Economics, Vetted and Real-Time Papers, from CEPR, brings together formal investigations on the economic issues emanating from the Covid outbreak, based on explicit theory and/or empirical evidence, to improve the knowledge base. Founder: Beatrice Weder di Mauro, President of CEPR Editor: Charles Wyplosz, Graduate Institute Geneva and CEPR Contact: Submissions should be made at https://portal.cepr.org/call-papers- covid-economics. Other queries should be sent to [email protected]. Copyright for the papers appearing in this issue of Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers is held by the individual authors. The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) is a network of over 1,500 research economists based mostly in European universities. The Centre’s goal is twofold: to promote world-class research, and to get the policy-relevant results into the hands of key decision-makers. CEPR’s guiding principle is ‘Research excellence with policy relevance’. A registered charity since it was founded in 1983, CEPR is independent of all public and private interest groups. It takes no institutional stand on economic policy matters and its core funding comes from its Institutional Members and sales of publications. Because it draws on such a large network of researchers, its output reflects a broad spectrum of individual viewpoints as well as perspectives drawn from civil society. -

COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptability in the UK at the Start of the Vaccination Programme: a Nationally Representative Cross-Sectio

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.06.21254973; this version posted April 8, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY 4.0 International license . COVID-19 vaccination acceptability in the UK at the start of the vaccination programme: a nationally representative cross- sectional survey (CoVAccS – wave 2) Susan M. Sherman1 PhD, Julius Sim2 PhD, Megan Cutts1 MSc, Hannah Dasch3,4 MSc, Richard Amlôt5,6 PhD, G James Rubin4,6 PhD, Nick Sevdalis3,4 PhD, Louise E. Smith4,6 PhD, 1 Keele University, School of Psychology 2 Keele University, School of Medicine 4 King’s College London, Centre for Implementation Science 6 King’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience 3 Public Health England, Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science and Technology 5 NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Emergency Preparedness and Response Corresponding author: Susan M. Sherman, [email protected] 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.06.21254973; this version posted April 8, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY 4.0 International license . -

Making Medicine… Anywhere

NOVEMBER 2020 # 70 Upfront In My View NextGen Sitting Down With Reducing the carbon The scavengers’ guide Pharma vs diabetes: Will Downie, CEO footprint of clinical trials to precious metal catalysts progress so far of Vectura Group, UK 08 13 46 – 49 50 – 51 Making Medicine… Anywhere How can biologics be made on-demand in deep space environments? 18 – 27 www.themedicinemaker.com Contract Manufacturing Excellence Experts in Viral Vector (AAV, adenovirus and lentiviral vectors) and Plasmid DNA (non-GMP, High Quality and GMP) manufacturing for pre- clinical, clinical and commercial supply. Visit our website to find out more and take a virtual tour: www.cobrabio.com Cobra Biologics is part of the Cognate BioServices family Beyond the Storm What happens after COVID-19? Editorial ack in 2017, we explored what healthcare and pharma might look like in 100 years’ time (1); the experts I spoke with were intrigued by the Bpremise, but were quick to point out that it’s hard to predict what will happen in five years’ time – and so virtually impossible to imagine a world in 2100 (although they still tried!). As 2020 has proven, even six months can seem like a very long time. The term “COVID-19” didn’t exist in November 2019, but by mid-March it was a household name, with most of us living in lockdown, trying to come to terms with how quickly a black swan event can transform our lives. Right now, I don’t know what 2021 will look like, but I do know that a single revolutionary medicine or vaccine could significantly transform the COVID-19 outlook. -

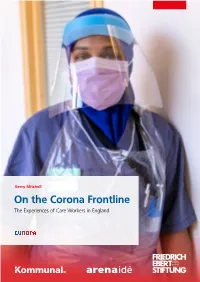

On the Corona Frontline. the Experiences of Care Workers in England

Gerry Mitchell On the Corona Frontline The Experiences of Care Workers in England FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG – POLITICS FOR EUROPE Europe needs social democracy! Why do we really want Europe? Can we demonstrate to European citizens the opportunities offered by social politics and a strong social democracy in Europe? This is the aim of the new Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung project »Politics for Europe«. It shows that European integration can be done in a democratic, economic and socially balanced way and with a reliable for- eign policy. The following issues will be particularly important: – Democratic Europe – Social and ecological transformation – Economic and social policy in Europe – Foreign and security policy in Europe We focus on these issues in our events and publications. We provide impetus and offer advice to decision-makers from politics and trade unions. Our aim is to drive the debate on the future of Europe forward and to develop specific propos- als to shape central policy areas. With this publication series we want to engage you in the debate on the »Politics for Eu- rope«! About this publication This paper looks at the impact of COVID-19 on care workers and the people they care for in England. It explains why the care sector was so vulnerable to and ill-equipped for the pandemic and charts the delayed government response to it and how that was further impeded by a lack of integration between health and social care. It documents trade union campaigning on the health and safety of workers, the lack of or inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE), sick pay, accommodation and access to testing as well as their fight for longer-term reform, emphasising how the immediate problems in the sector are connected to its longer-term systemic issues. -

Proud to Be Part of the Local Community

Priory Post ENJOY | RESPECT | ACHIEVE SUMMER TERM ISSUE | 2020 Priory School – Proud to be part of the local community To show our support for the local community, Priory School’s staff and key worker children decorated the front of the main building IMPORTANT DATES with messages of support for the NHS and a giant rainbow – AUTUMN TERM the symbol of hope and better times ahead during the pandemic. SEPTEMBER The idea to display the giant rainbow was part of the school’s ethos of being at the heart of the community. Tuesday 1 : INSET Day Wednesday 2 : INSET Day 1 Thursday 3 : Year 7 only Friday 4 : Year 7 and 11 only Monday 7 : Year 7, 10 and 11 only Tuesday 8 : All year groups in OCTOBER Monday 26 - Friday 30 : Half Term DECEMBER Friday 18 : Final day of term Please check the Priory School website for updates on calendar dates at the start of term subject to Covid-19 updates. Full Autumn term dates will be communicated as soon as possible. Relevant dates will also be posted on our Facebook page. Headteacher Mr Vaughan said, www.priorysouthsea.org “ It’s an expression of one of our core values to support the local community. We’d seen a number of rainbows on people’s houses and @PrioryOfficial decided it was something we would like to do. It was produced by our key worker children who have parents working on the front line and is @PriorySouthsea an expression of our pride for them and our support for the NHS.” Headteacher’s Message Dear Parents and Carers I think that I can reasonably say that this has been the most unusual term in my twenty-seven-year career to date.