Bowing out Clear and Present Danger Edward S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Reading Suggestions

Summer Reading Suggestions Tom Clancy Talking Books 1. Airborne: A Guided Tour of an Airborne Task Force DB051722 Describes an elite fighting unit of the army and air force--the 82nd Airborne Division--including its personnel, technology, and mission. Also, presents two short stories creating scenarios illustrating the fighting capacity of the unit. 2. Submarine: A Guided Tour Inside a Nuclear Warship DB037742 After a brief history and explanation of building techniques and crew qualifications, Clancy goes aboard a 688I. He explains every aspect of the U.S.S. Miami before moving on to tour a British vessel and provide updates on submarines throughout the world. 3. Into the Storm: A Study in Command DB044821 A study in modern military leadership as seen through the eyes of retired army general Fred Franks, who served in the Vietnam and Gulf wars. Discusses the theory, strategy, and doctrines of war. 4. Special Forces: A Guided Tour of U.S. Army Special Forces DB052128 Portrait of the Green Berets. Discusses their recruitment and training, equipment, and missions. Includes an interview with General Hugh Shelton, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and ends with a mini- novel depicting a terrorist revolution in Indonesia. 5. Against All Enemies DB073301 After his mission to take custody of a high-ranking Taliban prisoner goes horribly wrong, a former Navy SEAL is asked to return to America and investigate an alliance between the Taliban and a Mexican drug cartel. Large Print 1. Clear and Present Danger LT013868 Jack Ryan must consider when it is appropriate to respond to criminal activity with military force when Colombian drug lords assassinate three American officials. -

The Clear and Present Danger Standard: Its Present Viability, 6 U

University of Richmond Law Review Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 7 1971 The leC ar and Present Danger Standard: Its Present Viability Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation The Clear and Present Danger Standard: Its Present Viability, 6 U. Rich. L. Rev. 93 (1971). Available at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol6/iss1/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Richmond Law Review by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES THE CLEAR AND PRESENT DANGER STANDARD: ITS PRESENT VIABILITY The first amendment to the Constitution of the United States pro- vides that "Congress shall make no law ... abridging the freedom of speech or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble. •.." 1 While the terms of the first amendment appear to be all embrac- ing, its application has never been absolute. Its guarantees have always been subject to regulation by the state wherever they endangered the safety or welfare of the public.2 The fundamental issue involved in all first amendment problems involving free expression is the determina- tion of the point at which the rights of the individual stop and the rights of organized society to protect itself begin. The Constitution places on the courts the duty to draw the line between these two conflicting interests.3 The courts must, in each instance, ascertain which of the two interests require the greater protection. -

Wigglin' and Wrigglin' at the Love Shack Sylvester Stallone's Butt And

Music ÇA Film 7A Wigglin’ Sylvester and Wrigglin' Stallone's at the Love Butt and Shack The Arts and Entertainment Section of the Daily Nexus/For the Week of January 11-18,1990 Of Note This Week: Top 5 This Week at Morninglory Music 1. Hie Ministry, “A Mind Is A Terrible Thing To Taste” 2. Lenny Kravitz, “Let Love Rule” 3. Indigo Girls, “Strange Fire” 4. Bob Marley, “Legend” 5. Jesus and Mary Chain, “Automatic” at Sam Goody Records 1. Milli Vanilli, “Girl You Know It’s True” 2. The B-52’s, “Cosmic Thing” 3. Janet Jackson, “Rhythm Nation” 4. Soul II Soul, “Keep On Movin’” 5. Phil Collins, “But Seriously” Tonight: “Wings of Desire,” at Campbell Hall, 8 p.m.; $3/students, $4/non-students. Friday: “Up In Smoke,” at Campbell Hall, 7,9,11 p.m.; $3. Sunday: “Heavy Petting,” at Campbell Hall, 8 p.m.; $3/students, $4/non-students. ' V T hat were the top five records of the year? □ 1 fk / We’re sure the question has been around as long as music it- Tonight: u y self, and it has given people something to talk about at boring Dance — Repertory-West Dance Com pany, at the Main Theater, 8 p.m.; i ■ social functions from a long way back. through Saturday, $8. “No way, man. Moliere’s stuff beats the %$*&! out of Mo zart.... Elvis who? I liked the Pat Boonerecord a lotmore.... Yeah, Paula Abdul dances pretty good, but Milli Vanilli has great hair. ” ARTSWEEK asked this question of lots of people in the name of truth, justice and Milli Vanilli’s hair, and got a whole lot of different answers. -

Amazon Greenlights 10-Episode Season of Tom Clancy's Jack Ryan

Amazon Greenlights 10-Episode Season of Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan, Exclusively for Amazon Prime Video August 16, 2016 New Amazon Original series is slated to star John Krasinski Set to be co-produced by Paramount and Skydance Television and executive produced by Carlton Cuse, Graham Roland, Michael Bay, Brad Fuller, Andrew Form, David Ellison, Dana Goldberg, Marcy Ross, Mace Neufeld and Lindsey Springer In addition to unlimited video streaming on Prime Video, Amazon Prime members enjoy unlimited One-Day Delivery on millions of items, more than a million songs available to stream and download through Prime Music, unlimited photo storage in Amazon Cloud Drive, access to a million Kindle books to borrow, and early access to select Lightning Deals on www.amazon.co.uk — all available for a monthly membership of £7.99/month, or a best value annual membership of just £79/year. New customers can enjoy a free 30-day trial of Amazon Prime today by visiting www.amazon.co.uk/primevideo. LONDON—August 16, 2016—Amazon today announced it has greenlitTom Clancy’s Jack Ryan from Paramount and Skydance Television, to debut on Amazon Prime Video. The one-hour, 10-episode dramatic series is slated to star John Krasinski (13 Hours, The Office) as Jack Ryan and is projected to shoot in the US, Europe and Africa. Jack Ryan is a reinvention with a modern sensibility of the famed and lauded Tom Clancy hero, a character with a star-filled Hollywood history, having been previously portrayed by Alec Baldwin, Harrison Ford, Ben Affleck and Chris Pine. -

Some Notes on the Proper Uses of the Clear and Present Danger Test James W

BYU Law Review Volume 1978 | Issue 1 Article 3 3-1-1978 Some Notes on the Proper Uses of the Clear and Present Danger Test James W. Torke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation James W. Torke, Some Notes on the Proper Uses of the Clear and Present Danger Test, 1978 BYU L. Rev. 1 (1978). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol1978/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Notes on the Proper Uses of the Clear and Present Danger Test James W. Torke* Since its formulation in 1919 in Schenck v. United States,' the clear and present danger test has drifted uncertainly through changing styles of free speech doctrine. Promulgated by a unani- mous C~urt,~next used as a dissenters' banner,3 then employed by majorities4 and even an apparent, if occasional, con~ensus,~ sometime after its drastic reformulation in 1951 in Dennis u. United States6 it surely fell from whatever general grace it had enjoyed. Since that time, its use, at least its explicit use, has been confined to a few specific instances such as contempt cases in- volving free speech claims.' Later I will contend that the clear and present danger test has been more widely used, although in masked form, than has been admitted and that its value lies in more than its vivid form.8 But for now I wish to suggest the extent of its rejection. -

Lincoln, the Constitution of Necessity, and the Necessity of Constitutions: a Reply to Professor Paulsen

Maine Law Review Volume 59 Number 1 Article 2 January 2007 Lincoln, the Constitution of Necessity, and the Necessity of Constitutions: A Reply to Professor Paulsen Michael Kent Curtis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/mlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation Michael K. Curtis, Lincoln, the Constitution of Necessity, and the Necessity of Constitutions: A Reply to Professor Paulsen, 59 Me. L. Rev. 1 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/mlr/vol59/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LINCOLN, THE CONSTITUTION OF NECESSITY, AND THE NECESSITY OF CONSTITUTIONS: A REPLY TO PROFESSOR PAULSEN Michael Kent Curtis I. INTRODUCTION II. LINCOLN'S EARLY EXERCISE AND INVOCATION OF THE DOCTRINE OF NECESSITY III. THE CASE OF CLEMENT V ALLANDIGHAM IV. PROFESSOR PAULSEN ON LINCOLN'S CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES A. Lincoln as Anticipating Speech Plus Action Analysis B. Lincoln as Anticipating the Clear and Present Danger Test C. Lincoln as Anticipating and Applying the Compelling State Interest Test D. The Anything Needed to Win Principle V. REFLECTIONS ON THE PAULSEN ANALYSIS A. Speech-Action B. Clear and Present Danger C. The Compelling State Interest Test D. The Anything Needed to Win Principle VI. -

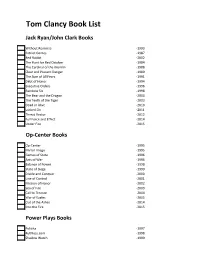

Tom Clancy Book List

Tom Clancy Book List Jack Ryan/John Clark Books Without Remorse -1993 Patriot Games -1987 Red Rabbit -2002 The Hunt for Red October -1984 The Cardinal of the Kremlin -1988 Clear and Present Danger -1989 The Sum of All Fears -1991 Debt of Honor -1994 Executive Orders -1996 Rainbow Six -1998 The Bear and the Dragon -2000 The Teeth of the Tiger -2003 Dead or Alive -2010 Locked On -2011 Threat Vector -2012 Full Force and Effect -2014 Under Fire -2015 Op-Center Books Op-Center -1995 Mirror Image -1995 Games of State -1996 Acts of War -1996 Balance of Power -1998 State of Siege -1999 Divide and Conquer -2000 Line of Control -2001 Mission of Honor -2002 Sea of Fire -2003 Call to Treason -2004 War of Eagles -2005 Out of the Ashes -2014 Into the Fire -2015 Power Plays Books Politika -1997 Ruthless.com -1998 Shadow Watch -1999 Bio-Strike -2000 Cold War -2001 Cutting Edge -2002 Zero Hour -2003 Wild Card -2004 Net Force Books Net Force -1999 Hidden Agendas -1999 Night Moves -1999 Breaking Point -2000 Point of Impact -2001 CyberNation -2001 State of War -2003 Changing of the Guard -2003 Springboard -2005 The Archimedes Effect -2006 Net Force Explorers Books Virtual Vandals -1998 The Deadliest Game -1998 One is the Loneliest Number -1999 The Ultimate Escape -1999 The Great Race -1999 End Game -1998 Cyberspy -1999 Shadow of Honor -2000 Private Lives -2000 Safe House -2000 Gameprey -2000 Duel Identity -2000 Deathworld -2000 High Wire -2001 Cold Case -2001 Runaways -2001 Splinter Cell Books Splinter Cell -2004 Operation Barracuda -2005 Checkmate -2006 Fallout -2007 Conviction -2009 Endgame -2009 Blacklist Aftermath -2013 Ghost Recon Books Ghost Recon -2008 Combat Ops -2011 EndWar Books EndWar -2008 The Hunted -2011 H.A.W.X. -

On Cyberwarfare

DCAF HORIZON 2015 WORKING PAPER No. 7 On Cyberwarfare Fred Schreier DCAF HORIZON 2015 WORKING PAPER No. 7 On Cyberwarfare Fred Schreier Table of Contents On Cyberwarfare 7 1. The Basic Building Blocks: Cyberspace, Cyberpower, Cyberwarfare, and Cyberstrategy 10 2. The Difference between Information Warfare and Cyberwarfare 19 3. Understanding the Threats in Cyberspace 31 4. Cyber Vulnerabilities and how Cyber Attacks are Enabled 48 5. Major Issues, Ambiguities, and Problems of Cyberwar 68 Annex 1: In which Ways is Cyberwar different from the other Warfighting Domains? 93 Annex 2: Summary of major Incidents of Cyber Conflict 107 Glossary 116 Select Bibliography 121 DCAF HORIZON 2015 WORKING PAPER 5 6 DCAF HORIZON 2015 WORKING PAPER On Cyberwarfare The digital world has brought about a new type of clear and present danger: cyberwar. Since information technology and the internet have developed to such an extent that they have become a major element of national power, cyberwar has become the drumbeat of the day as nation-states are arming themselves for the cyber battlespace. Many states are not only conducting cyber espionage, cyber reconnaissance and probing missions; they are creating offensive cyberwar capabilities, developing national strategies, and engaging in cyber attacks with alarming frequency. Increasingly, there are reports of cyber attacks and network infiltrations that can be linked to nation-states and political goals. What is blatantly apparent is that more financial and intellectual capital is being spent figuring out how to conduct cyberwarfare than for endeavors aiming at how to prevent it.1 In fact, there is a stunning lack of international dialogue and activity with respect to the containment of cyberwar. -

On “Clear and Present Danger”

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\94-4\NDL405.txt unknown Seq: 1 29-MAY-19 15:33 ON “CLEAR AND PRESENT DANGER” Leslie Kendrick* INTRODUCTION Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s dissent in United States v. Abrams gave us the “marketplace of ideas” metaphor and the “clear and present danger” test.1 Too often unremarked is the contradiction between the two. At the same time that Holmes says “the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market,” he also says that “the present danger of immediate evil” permits Congress to restrict the expression of opinion.2 When the anticipated harm comes about through acceptance of the speaker’s idea, then the imposition of the clear and present danger test stops the operation of the marketplace of ideas.3 The market is not free if the clear and present danger test intervenes right when an idea gains traction. In Abrams, the “evil” that preoccupied Congress was the embrace of socialism and concomitant opposition to the World War I draft. The five defendants in Abrams had printed and distributed circulars aimed at persuad- ing the market to accept the truth of their socialist perspective on the war.4 Holmes concluded that the printing and distribution of the circulars did not present a clear and present danger. “[N]obody,” he said, “can suppose that the surreptitious publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man, without © 2019 Leslie Kendrick. Individuals and nonprofit institutions may reproduce and distribute copies of this Article in any format at or below cost, for educational purposes, so long as each copy identifies the author, provides a citation to the Notre Dame Law Review, and includes this provision in the copyright notice. -

Thirty Years Ago, Tom Clancy Was a Maryland Insurance Broker with a Passion for Naval History. Years Before, He Had Been an Engl

Thirty years ago, Tom Clancy was a Maryland insurance broker with a passion for naval history. Years before, he had been an English major at Baltimore’s Loyola College and had always dreamed of writing a novel. His first effort, The Hunt for Red October, sold briskly as a result of rave reviews, then catapulted onto the New York Times bestseller list after President Reagan pronounced it “the perfect yarn.” From that day forward, Clancy established himself as an undisputed master at blending exceptional realism and authenticity, intricate plotting, and razor-sharp suspense. He passed away in October 2013. Mike Maden grew up working in the canneries, feed mills, and slaughterhouses of California’s San Joaquin Valley. A lifelong fascination with history and warfare ultimately led to a Ph.D. in political science, focused on conflict and technology in international relations. Like millions of others, he first became a Tom Clancy fan after reading The Hunt for Red October; he began his published fiction career in the same techno-thriller genre with Drone and continued with the sequels, Blue Warrior, Drone Command, and Drone Threat. Maden is honored to be “joining The Campus” as a writer in Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan, Jr., series. 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 TOM CLANCY 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 S30 N31 9780735215924_LineOfSight_TX.indd i 3/14/18 12:03 AM ALSO BY TOM CLANCY 01 FICTION 02 The Hunt for Red October 03 Red Storm Rising Patriot Games 04 The Cardinal of the Kremlin 05 Clear and Present Danger The Sum of -

Case No. 17-35105 in the United States Court of Appeals

(1 of 42) Case: 17-35105, 02/06/2017, ID: 10304535, DktEntry: 84-1, Page 1 of 40 CASE NO. 17-35105 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT STATE OF WASHINGTON, et al., Appellants v. DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT, et al., Appellees ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON, CASE NO. 2:17-cv-00141-JLR. BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FREEDOM WATCH, INC., IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS-DEFENDANTS ON EMERGENCY MOTION FOR STAY PENDING APPEAL ORAL ARGUMENT REQUESTED Larry Klayman, Esq. FREEDOM WATCH, INC. 2020 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, Suite 345 Washington, DC 20006 Telephone: (561) 997-9956 Email: [email protected] Attorney for Amicus Curiae February 7, 2017 (2 of 42) Case: 17-35105, 02/06/2017, ID: 10304535, DktEntry: 84-1, Page 2 of 40 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ii FRAP RULE 26.1 AND FRAP 29(a)(4)(E) DISCLOSURE STATEMENT iii STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE iv I. SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 1 II. ARGUMENT 3 A. Appellee States Will Fail On The Merits 3 B. President's Power To Regulate Entry Into The United States Is Clear And Almost Unlimited 4 C. Executive Order Targets "Failed States" Plus Terrorist Sponsor, Hostile Iran, Not Religion 4 D. Appellees Misrepresent 8 U.S.C. § 1152(A)(1)(A) 7 E. Straw-Man Argument Of Religious Discrimination 10 F. Irreparable Harm Supports The Executive Order, Not The Appellees 12 G. Enjoining The Executive Order Is Mistaken 15 I. Forum Non Conveniens And Judge Shopping 16 III. -

Does the Clear and Present Danger Test Survive Cost-Benefit Analysis?

Cornell Law Review Volume 104 Issue 7 November 2019 Article 3 11-2019 Does the Clear and Present Danger Test Survive Cost-Benefit Analysis? Cass R. Sunstein Harvard University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Cass R. Sunstein, Does the Clear and Present Danger Test Survive Cost-Benefit Analysis?, 104 Cornell L. Rev. 1775 (2020) Available at: https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol104/iss7/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOES THE CLEAR AND PRESENT DANGER TEST SURVIVE COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS? Cass R. Sunsteint Under American regulatory law, the dominant contempo- rary test involves cost-benefit analysis. The benefits of regula- tion mustjustify the costs; if they do, regulationis permissible and even mandatory. Under American free speech law, in sharp contrast, an important contemporary test for the regula- tion of speech involves "clearand present danger." In general, officials cannot censor or regulate political speech on the ground that the benefits of regulationjustify the costs. They may proceed only if the speech is likely to produce immtinent lawless action. In principle,it is not simple to explain why the free speech test does not involve cost-benefit analysis, as in- deed both Judge Learned Hand and the Supreme Court in- sisted that it should in the early 1950s.