On Cyberwarfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalism; *Peace; Political Attitudes; Slvery; Terrorism; Violence; War; World Problems IDENTIFIERS *Africa; *Peace Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 396 074 CE 070 196 AUTHOR Kisembo, Paul TITLE A Popular Version of Yash Tandon's Militarism and Peace Education in Africa. INSTITUTION African Association for Literacy and Adult Education. Nairobi (Kenya). PUB DATE 93 NOTE 52p. PUB TYPE Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plhs Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; *Civil Liberties; Civil Rights; *Colonialisn; Community Education; Conflict Resolution; Developing Nations; Economic Development; Foreign Countries; *Freedom; International Relations; *Nationalism; *Peace; Political Attitudes; Slvery; Terrorism; Violence; War; World Problems IDENTIFIERS *Africa; *Peace Education ABSTRACT This book is a briefer, simpler popular edition of "Militarism and Peace Education in Africa." It is intended to interest the African peoples in the problems of peace and allow them to discuss and debate the issues of militarism and peace for Africa and to suggest solutions. It is also intended to interest leading organizations and people working at the grassroots level in urban and rural areas in problems of militarism and peace education. The first two chapters show hoW, in former times, militarism was brought to Africa by the Europeans through slave trade and colonialism. Chapter 3 shows how militarism continued after independence under neocolonialism in these forms: state terrorism, militarism based on ethnic nationality/conflicts, militarism resulting from "pastoralist conflicts," militarism resulting from cultural and religious conflicts, and militarism based on ideological conflicts. Chapter 4 explores how militarism is still connected to the exploitation and oppression of Africa with the new strategy called "low intensity conflict" or "low intensity war." Chapter 5 considers developing types of peace education and proposed content of peace education. -

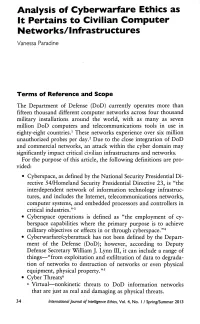

Analysis of Cyberwarfare Ethics As It Pertains to Civilian Computer Networks/Infrastructures

Analysis of Cyberwarfare Ethics as It Pertains to Civilian Computer Networks/Infrastructures Vanessa Paradine Terms of Reference and Scope The Department of Defense (DoD) currently operates more than fifteen thousand different computer networks across four thousand military installations around the world, with as many as seven million DoD computers and telecommunications tools in use in eighty-eight countries.1 These networks experience over six million unauthorized probes per day.2 Due to the close integration of DoD and commercial networks, an attack within the cyber domain may significantly impact critical civilian infrastructures and networks. For the purpose of this article, the following definitions are pro vided: • Cyberspace, as defined by the National Security Presidential Di rective 541H0meland Security Presidential Directive 23, is "the interdependent network of information technology infrastruc tures, and includes the Internet, telecommunications networks, computer systems, and embedded processors and controllers in critical industries."3 • Cyberspace operations is defined as "the employment of cy berspace capabilities where the primary purpose is to achieve military objectives or effects in or through cyberspace."4 • Cyberwarfare/cyberattack has not been defined by the Depart ment of the Defense (DoD); however, according to Deputy Defense Secretary William J. Lynn III, it can include a range of things-"from exploitation and exfiltration of data to degrada tion of networks to destruction of networks or even physical equipment, physical property."5 • Cyber Threats6 o Virtual-nonkinetic threats to DoD information networks that are just as real and damaging as physical threats. 34 Internatianal Journal of Intelligence Ethics, Vol. 4, No. 1 / Spring/Summer 2013 Analysis of Cyberwarfare Ethics 35 o Physical-kinetic threats mixed with nonkinetic threats; can severely impact the effectiveness of military joint operations. -

Botnets, Cybercrime, and Cyberterrorism: Vulnerabilities and Policy Issues for Congress

Order Code RL32114 Botnets, Cybercrime, and Cyberterrorism: Vulnerabilities and Policy Issues for Congress Updated January 29, 2008 Clay Wilson Specialist in Technology and National Security Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Botnets, Cybercrime, and Cyberterrorism: Vulnerabilities and Policy Issues for Congress Summary Cybercrime is becoming more organized and established as a transnational business. High technology online skills are now available for rent to a variety of customers, possibly including nation states, or individuals and groups that could secretly represent terrorist groups. The increased use of automated attack tools by cybercriminals has overwhelmed some current methodologies used for tracking Internet cyberattacks, and vulnerabilities of the U.S. critical infrastructure, which are acknowledged openly in publications, could possibly attract cyberattacks to extort money, or damage the U.S. economy to affect national security. In April and May 2007, NATO and the United States sent computer security experts to Estonia to help that nation recover from cyberattacks directed against government computer systems, and to analyze the methods used and determine the source of the attacks.1 Some security experts suspect that political protestors may have rented the services of cybercriminals, possibly a large network of infected PCs, called a “botnet,” to help disrupt the computer systems of the Estonian government. DOD officials have also indicated that similar cyberattacks from individuals and countries targeting economic, -

The Effectiveness of Influence Activities in Information Warfare

The Effectiveness of Influence Activities in Information Warfare Cassandra Lee Brooker A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Research School of Business May 2020 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname : BROOKER Given Name/s : CASSANDRA LEE Abbreviation for degree : MRes Faculty : UNSW Canberra School : School of Business Thesis Title : The Effectiveness of Influence Activities in Information Warfare Abstract Rapid, globalised power shifts, technological advances, and increasingly interconnected, ungoverned communications networks have resulted in the rise of asymmetric grey zone threats. The lines are now blurred between political, civil, and military information environments. The rise of influence activities is the new ‘sharp power’ in information warfare (the iWar). Western democracies are already at war in the information domain and are being out-communicated by their adversaries. Building on the commentary surrounding this contemporary threat, and based on a review of the literature across three academic disciplines of: Systems Thinking, Influence, and Cognitive Theory; this study aimed to investigate solutions for improving Australia’s influence effectiveness in the iWar. This study asked how systems thinking can offer an effective approach to holistically understanding complex social systems in the iWar; as well as asking why understanding both successful influencing strategies and psychological cognitive theories is central to analysing those system behaviours. To answer the aim, a systems thinking methodology was employed to compare two contrasting case studies to determine their respective influencing effectiveness. The successful case system comprising the terrorist group ISIS was compared and contrasted with the unsuccessful case system of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 election campaign – using a single stock of influence to determine relevant reinforcing and balancing feedback. -

Ransomware Facts and Tips

RANSOMWARE FACTS & TIPS As technology evolves, the prevalence of ransomware attacks is growing among businesses and consumers alike. It’s important for digital citizens to be vigilant about basic digital hygiene in an increasingly connected world. WHAT IS RANSOMWARE? Ransomware is a type of malware that accesses a victim’s files, locks and encrypts them and then demands the victim to pay a ransom to get them back. Cybercriminals use these attacks to try to get users to click on attachments or links that appear legitimate but actually contain malicious code. Ransomware is like the “digital kidnapping” of valuable data – from personal photos and memories to client information, financial records and intellectual property. Any individual or organization could be a potential ransomware target. WHAT CAN YOU DO? We can all help protect ourselves – and our organizations – against ransomware and other malicious attacks by following these STOP. THINK. CONNECT. tips: • Keep all machines clean: Keep the software on all Internet-connected devices up to date. All critical software, including computer and mobile operating systems, security software and other frequently used programs and apps, should be running the most current versions. • Get two steps ahead: Turn on two-step authentication – also known as two-step verification or multi-factor authentication – on accounts where available. Two-factor authentication can use anything from a text message to your phone to a token to a biometric like your fingerprint to provide enhanced account security. • Back it up: Protect your valuable work, music, photos and other digital information by regularly making an electronic copy and storing it safely. -

Cost of a Cyber Incident)

CO ST OF A CYBER INCIDENT: S YSTEMATIC REVIEW AND C ROSS-VALIDATION OCTOBER 26, 2020 1 Acknowledgements We are grateful to Dr. Allan Friedman, Dr. Lawrence Gordon, Jay Jacobs, Dr. Sasha Romanosky, Matthew Shabat, Kelly Shortridge, Steven Surdu, David Tobar, Brett Tucker and Sounil Yu for the review comments and helpful feedback on the earlier draft of the report. The authors would like to thank CISA staff for support and advice on this project. 2 Table of Contents 1. Objectives .................................................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Results in Brief .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 3. Analysis ...................................................................................................................................................................... 16 3.1. Per-Incident Cost and Loss Estimates .............................................................................................. 18 3.1.1. Cross-Validation: Primary Loss Data for Large and Small Incidents .................................. 20 3.1.2. Reconciliation of Per-Incident Cost Studies .................................................................................. 26 3.1.3. Per-Record Estimates ............................................................................................................................. 29 3.2. Aggregate -

Attribution and Response to Cybercrime/Terrorism/Warfare Susan W

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 97 Article 2 Issue 2 Winter Winter 2007 At Light Speed: Attribution and Response to Cybercrime/Terrorism/Warfare Susan W. Brenner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Susan W. Brenner, At Light Speed: Attribution and Response to Cybercrime/Terrorism/Warfare, 97 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 379 (2006-2007) This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/07/9702-0379 THE JOURNALOF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 97. No. 2 Copyright 0 2007 by NorthwesternUniversity. Schoolof Low Printedin U.S.A. "AT LIGHT SPEED": ATTRIBUTION AND RESPONSE TO CYBERCRIME/TERRORISM/WARFARE SUSAN W. BRENNER* This Article explains why and how computer technology complicates the related processes of identifying internal (crime and terrorism) and external (war) threats to social order of respondingto those threats. First, it divides the process-attribution-intotwo categories: what-attribution (what kind of attack is this?) and who-attribution (who is responsiblefor this attack?). Then, it analyzes, in detail, how and why our adversaries' use of computer technology blurs the distinctions between what is now cybercrime, cyberterrorism, and cyberwarfare. The Article goes on to analyze how and why computer technology and the blurring of these distinctions erode our ability to mount an effective response to threats of either type. -

Agile Command Capability: Future Command in the Joint Battlespace and Its Implications for Capability Development

UNCLASSIFIED DRAFT AGILE COMMAND CAPABILITY: FUTURE COMMAND IN THE JOINT BATTLESPACE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR CAPABILITY DEVELOPMENT Steven J. Harland, MPhil(Cantab), C. Psychol, FRSA Gregory Harland Ltd Surrey Research Park Guildford GU2 7YG United Kingdom Paul J. Shanahan, PhD Gregory Harland Ltd Surrey Research Park Guildford GU2 7YG United Kingdom Cdr David J. Bewick MA RN Command Development Directorate of Command and Battlespace Management/J6 Ministry of Defence St Giles Court 1-13 St Giles High Street London WC2H 8LD United Kingdom UNCLASSIFIED DRAFT UNCLASSIFIED DRAFT AGILE COMMAND CAPABILITY: FUTURE COMMAND IN THE JOINT BATTLESPACE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR CAPABILITY DEVELOPMENT1 Steven J. Harland, MPhil(Cantab), C. Psychol, FRSA Gregory Harland Ltd Surrey Research Park Guildford GU2 7YG United Kingdom Paul J. Shanahan, PhD Gregory Harland Ltd Surrey Research Park Guildford GU2 7YG United Kingdom Cdr David J. Bewick, MA RN Command Development Directorate of Command and Battlespace Management/J6 Ministry of Defence St Giles Court 1-13 St Giles High Street London WC2H 8LD United Kingdom Command cannot be understood in isolation. The available data processes technology and the nature of armaments in use; tactics and strategy; organisational structure and manpower systems; training, discipline, and…the ethos of war; the political construction of states and the social makeup of armies – all these things and many more impinge on command in war and in turn are affected by it.2 Martin van Creveld, Command in War ABSTRACT The paper defines the Ministry of Defence (MoD) requirements for Future Command3 within the context of the United Kingdom’s (UK) Joint Higher Level Operational Concept (HLOC). -

The Order of Encryption and Authentication for Protecting Communications (Or: How Secure Is SSL?)?

The Order of Encryption and Authentication for Protecting Communications (Or: How Secure is SSL?)? Hugo Krawczyk?? Abstract. We study the question of how to generically compose sym- metric encryption and authentication when building \secure channels" for the protection of communications over insecure networks. We show that any secure channels protocol designed to work with any combina- tion of secure encryption (against chosen plaintext attacks) and secure MAC must use the encrypt-then-authenticate method. We demonstrate this by showing that the other common methods of composing encryp- tion and authentication, including the authenticate-then-encrypt method used in SSL, are not generically secure. We show an example of an en- cryption function that provides (Shannon's) perfect secrecy but when combined with any MAC function under the authenticate-then-encrypt method yields a totally insecure protocol (for example, ¯nding passwords or credit card numbers transmitted under the protection of such protocol becomes an easy task for an active attacker). The same applies to the encrypt-and-authenticate method used in SSH. On the positive side we show that the authenticate-then-encrypt method is secure if the encryption method in use is either CBC mode (with an underlying secure block cipher) or a stream cipher (that xor the data with a random or pseudorandom pad). Thus, while we show the generic security of SSL to be broken, the current practical implementations of the protocol that use the above modes of encryption are safe. 1 Introduction The most widespread application of cryptography in the Internet these days is for implementing a secure channel between two end points and then exchanging information over that channel. -

A Taxonomy of Computer Worms ∗

A Taxonomy of Computer Worms ∗ † ‡ § ¶ Nicholas Vern Stuart Robert Weaver Paxson Staniford Cunningham UC Berkeley ICSI Silicon Defense MIT Lincoln Laboratory ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION To understand the threat posed by computer worms, it is A computer worm is a program that self-propagates across necessary to understand the classes of worms, the attackers a network exploiting security or policy flaws in widely-used who may employ them, and the potential payloads. This pa- services. They are not a new phenomenon, having first per describes a preliminary taxonomy based on worm target gained widespread notice in 1988 [16]. discovery and selection strategies, worm carrier mechanisms, We distinguish between worms and viruses in that the worm activation, possible payloads, and plausible attackers latter infect otherwise non-mobile files and therefore require who would employ a worm. some sort of user action to abet their propagation. As such, viruses tend to propagate more slowly. They also have more Categories and Subject Descriptors mature defenses due to the presence of a large anti-virus industry that actively seeks to identify and control their D.4.6 [Operating Systems]: Security and Protection—In- spread. vasive Software We note, however, that the line between worms and viruses is not all that sharp. In particular, the contagion worms General Terms discussed in Staniford et al [47] might be considered viruses Security by the definition we use here, though not of the traditional form, in that they do not need the user to activate them, but Keywords instead they hide their spread in otherwise unconnected user activity. Thus, for ease of exposition, and for scoping our computer worms, mobile malicious code, taxonomy, attack- analysis, we will loosen our definition somewhat and term ers, motivation malicious code such as contagion, for which user action is not central to activation, as a type of worm. -

Opentext Product Security Assurance Program

The Information Company ™ Product Security Assurance Program Contents Objective 03 Scope 03 Sources 03 Introduction 03 Concept and design 04 Development 05 Testing and quality assurance 07 Maintain and support 09 Partnership and responsibility 10 Privavy and Security Policy 11 Product Security Assurance Program 2/11 Objective The goals of the OpenText Product Security Assurance Program (PSAP) are to help ensure that all products, solutions, and services are designed, developed, and maintained with security in mind, and to provide OpenText customers with the assurance that their important assets and information are protected at all times. This document provides a general, public overview of the key aspects and components of the PSAP program. Scope The scope of the PSAP includes all software solutions designed and developed by OpenText and its subsidiaries. All OpenText employees are responsible to uphold and participate in this program. Sources The source of this overview document is the PSAP Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). This SOP is highly confidential in nature, for internal OpenText consumption only. This overview document represents the aspects that are able to be shared with OpenText customers and partners. Introduction OpenText is committed to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of its customer information. OpenText believes that the foundation of a highly secure system is that the security is built in to the software from the initial stages of its concept, design, development, deployment, and beyond. In this respect, -

Montesquieu on Commerce, Conquest, War and Peace Robert Howse

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 31 | Issue 3 Article 3 2006 Montesquieu on Commerce, Conquest, War and Peace Robert Howse Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Robert Howse, Montesquieu on Commerce, Conquest, War and Peace, 31 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol31/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. MONTESQUIEU ON COMMERCE, CONQUEST, WAR, AND PEACE * Robert Howse I. INTRODUCTION: COMMERCE AS THE AGENT OF PEACE: MONTESQUIEU AND THE IDEOLOGY OF LIBERALISM n the history of liberalism, Montesquieu, who died two hundred and I fifty years ago, is an iconic figure. Montesquieu is cited as the source of the idea of checks and balances, or separation of powers, and thus as an intellectual inspiration of the American founding.1 Among liberal internationalists, Montesquieu is known above all for the notion that international trade leads to peace among nation-states. When liberal international relations theorists such as Michael Doyle attribute this posi- tion to Montesquieu,2 they cite Book XX of the Spirit of the Laws,3 in which Montesquieu claims: “The natural effect of commerce is to bring peace. Two nations that negotiate between themselves become recipro- cally dependent, if one has an interest in buying and the other in selling. And all unions are based on mutual needs.”4 On its own, Montesquieu’s claim raises many issues.