Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2014 Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ramsar Sites in Order of Addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance

Ramsar sites in order of addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance RS# Country Site Name Desig’n Date 1 Australia Cobourg Peninsula 8-May-74 2 Finland Aspskär 28-May-74 3 Finland Söderskär and Långören 28-May-74 4 Finland Björkör and Lågskär 28-May-74 5 Finland Signilskär 28-May-74 6 Finland Valassaaret and Björkögrunden 28-May-74 7 Finland Krunnit 28-May-74 8 Finland Ruskis 28-May-74 9 Finland Viikki 28-May-74 10 Finland Suomujärvi - Patvinsuo 28-May-74 11 Finland Martimoaapa - Lumiaapa 28-May-74 12 Finland Koitilaiskaira 28-May-74 13 Norway Åkersvika 9-Jul-74 14 Sweden Falsterbo - Foteviken 5-Dec-74 15 Sweden Klingavälsån - Krankesjön 5-Dec-74 16 Sweden Helgeån 5-Dec-74 17 Sweden Ottenby 5-Dec-74 18 Sweden Öland, eastern coastal areas 5-Dec-74 19 Sweden Getterön 5-Dec-74 20 Sweden Store Mosse and Kävsjön 5-Dec-74 21 Sweden Gotland, east coast 5-Dec-74 22 Sweden Hornborgasjön 5-Dec-74 23 Sweden Tåkern 5-Dec-74 24 Sweden Kvismaren 5-Dec-74 25 Sweden Hjälstaviken 5-Dec-74 26 Sweden Ånnsjön 5-Dec-74 27 Sweden Gammelstadsviken 5-Dec-74 28 Sweden Persöfjärden 5-Dec-74 29 Sweden Tärnasjön 5-Dec-74 30 Sweden Tjålmejaure - Laisdalen 5-Dec-74 31 Sweden Laidaure 5-Dec-74 32 Sweden Sjaunja 5-Dec-74 33 Sweden Tavvavuoma 5-Dec-74 34 South Africa De Hoop Vlei 12-Mar-75 35 South Africa Barberspan 12-Mar-75 36 Iran, I. R. -

Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project

Submission to Senate Inquiry: Great Australian Bight BP Oil Drilling Project: Potential Impacts on Matters of National Environmental Significance within Modelled Oil Spill Impact Areas (Summer and Winter 2A Model Scenarios) Prepared by Dr David Ellis (BSc Hons PhD; Ecologist, Environmental Consultant and Founder at Stepping Stones Ecological Services) March 27, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 4 Summer Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................. 5 Winter Oil Spill Scenario Key Findings ................................................................... 7 Threatened Species Conservation Status Summary ........................................... 8 International Migratory Bird Agreements ............................................................. 8 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Methods .................................................................................................................... 12 Protected Matters Search Tool Database Search and Criteria for Oil-Spill Model Selection ............................................................................................................. 12 Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Threatened, Migratory and Marine -

Flinders Island Fire Management Area Bushfire Risk Management Plan

Flinders Island Fire Management Area Bushfire Risk Management Plan 2020 Document Control Document History Version Date Author Section 1.0 November 2019 L Dean Bushfire Risk Unit 2.0 December 2019 J Viney Flinders Council 3.0 February 2020 H Lloyd-Deely Bushfire Risk Unit Agency Endorsements Agency Name & Title Signature Date Flinders Council Jacci Viney 24/2/2020 Development Services Coordinator Document Endorsement Endorsed by Flinders Island Fire Management Area Committee Jacci Viney Development Services Coordinator Date: 24 February 2020 Accepted by State Fire Management Council Ian Sauer Chair, SFMC Date: 7 May 2020 Cover Page Photo Acknowledgement: Cultural Burning on Cape Barren Island/Truwana, L Dean, TFS Contents Contents ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Glossary ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 8 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................. -

Extent and Impacts of Dryland Salinity in Tasmania

National Land and Water Resources Audit Extent and impacts of Dryland Salinity in Tasmania Project 1A VOLUME 2 - APPENDICES C.H. Bastick and M.G. Walker Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment August 2000 DEPARTMENT of PRIMARY INDUSTRIES, WATER and ENVIRONMENT LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix 1 LAND SYSTEMS IN TASMANIA CONTAINING AREAS OF SALINITY................................................................1 Appendix 2 EXTENT, TRENDS AND ECONOMIC IMPACT OF DRYLAND SALINITY IN TASMANIA...................................16 Appendix 3 GROUND WATER ....................................................................28 Appendix 4(a) SURFACE WATER MONITORING .......................................32 Appendix 4(b) SURFACE WATER IN TASMANIA - An Overview ..............36 Appendix 5 POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF SALINITY ON BIODIVERSITY VALUES IN TASMANIA.............................46 Appendix 1 LAND SYSTEMS IN TASMANIA CONTAINING AREAS OF SALINITY 1 LAND SYSTEMS IN TASMANIA CONTAINING AREAS OF SALINITY · The Soil Conservation section of the Tasmanian Department of Agriculture between 1980 and 1989 carried out a series of reconnaissance surveys of the State's land resources. · It was intended that the data collected would allow a more rational approach to Tasmania's soil conservation problems and serve as a base for further studies, such as the detailed mapping of land resources in selected areas and the sampling of soils for physical and chemical analyses. It was therefore decided that this would be a logical framework on which to develop the Dryland Salinity Audit process. · Land resources result from the interaction of geology, climate, topography, soils and vegetation · Areas where these are considered to be relatively uniform for broad scale uses are classified as land components. Land components are grouped into larger entities called land systems, which are the mapping units used for this Audit. -

Atlas of Coastal Saltmarsh Wetlands in Northern

ATLAS OF COASTAL SALTMARSH WETLANDS IN NORTHERN TASMANIA Maps, photos and text: Vishnu Prahalad Design and layout: Michael Helman Published by NRM North, August 2014 NRM NORTH INTRODUCTION TO THE ATLAS Coastal saltmarshes in subtropical and temperate Australia (including Tasmania) were listed in 2013 as a vulnerable ecological community under Federal environment legislation (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999). Tis listing acknowledges that wetlands have sufered habitat fragmentation and loss of community integrity coupled with threats from human activities, invasive species and sea level rise. In Tasmania, studies show that close to half of these important coastal ecosystems have been lost due to these threats. Te vulnerability of Tasmanian saltmarshes is further underscored by a lack of broad awareness of the important values provided by these habitats. Saltmarsh wetlands perform important ecological functions that support a range of ecosystem services and biodiversity values in the coastal landscape, though they remain underappreciated and in many cases, lack baseline mapping information. Particularly in Northern Tasmania, saltmarsh wetlands were unmapped in several areas including the Tamar Estuary. Mapping these wetlands is, therefore, an important activity and also needs to be accompanied by products aimed at both communicating the mapping results and providing tools for better understanding and engagement in conserving these habitats and their ecological services. Tis atlas provides a visual summary of mapping undertaken as part of the Steps to Saltmarsh Conservation in Northern Tasmania project (completed in July 2014). Information is drawn from the GIS mapping layer that records the extent and location of saltmarshes and the accompanying database that contains information on a range of attributes pertaining to these mapped natural assets. -

Flinders Island Tasmania 20–30 March 2014

Flinders Island Tasmania 20–30 March 2014 Bush Blitz Species Discovery Program Flinders Island, Tasmania 20–30 March 2014 What is Bush Blitz? Bush Blitz is a multi-million dollar partnership between the Australian Government, BHP Billiton Sustainable Communities and Earthwatch Australia to document plants and animals in selected properties across Australia. This innovative partnership harnesses the expertise of many of Australia’s top scientists from museums, herbaria, universities, and other institutions and organisations across the country. Abbreviations ABRS Australian Biological Resources Study ANIC Australian National Insect Collection EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) TMAG Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery TSP Act Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 (Tasmania) UNSW University of New South Wales Page 2 of 32 Flinders Island, Tasmania 20–30 March 2014 Summary From 20–30 March 2014, a Bush Blitz survey was conducted on Flinders Island in Bass Strait. The island has eight reserves, including Strzelecki National Park. Flinders Island is one of the remaining parts of the land bridge between the Australian mainland and Tasmania. This history, plus the wide range of habitats from mountains to open shrubland and coastal areas, means that the island is highly diverse. The Bush Blitz survey recorded 862 species, 643 of which had not been recorded previously for the reserves. Thirty-nine species that may be new to science were identified, including 33 invertebrate species (3 moths, 1 beetle, 6 true bugs and 23 spiders) and 6 lichen species. One moth and 10 plant species listed under Tasmania’s Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 (TSP Act) were also collected. -

Download from And

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2014 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/doc/ris/key_ris_e.doc and http://www.ramsar.org/pdf/ris/key_ris_e.pdf Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 17, 4th edition). 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and DD MM YY Environment (DPIPWE) GPO Box 44 Hobart, Tasmania 7001 Telephone: +61 3 6165 4396 Designation date Site Reference Number [email protected] 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: April 2014 3. Country: Australia 4. Name of the Ramsar site: The precise name of the designated site in one of the three official languages (English, French or Spanish) of the Convention. -

Reserve Listing

Reserve Summary Report NCA Reserves Number Area (ha) Total 823 2,901,596.09 CONSERVATION AREA 438 661,640.89 GAME RESERVE 12 20,389.57 HISTORIC SITE 30 16,051.47 NATIONAL PARK 19 1,515,793.29 NATURE RECREATION AREA 25 67,340.19 NATURE RESERVE 86 118,977.14 REGIONAL RESERVE 148 454,286.95 STATE RESERVE 65 47,116.57 Total General Plan Total 823 2,901,596.09 823 2,901,596.09 CONSERVATION AREA 438 661,640.89 438 661,640.89 GAME RESERVE 12 20,389.57 12 20,389.57 HISTORIC SITE 30 16,051.47 30 16,051.47 NATIONAL PARK 19 1,515,793.29 19 1,515,793.29 NATURE RECREATION A 25 67,340.19 25 67,340.19 NATURE RESERVE 86 118,977.14 86 118,977.14 REGIONAL RESERVE 148 454,286.95 148 454,286.95 STATE RESERVE 65 47,116.57 65 47,116.57 CONSERVATION AREA Earliest Previous mgmt Name Mgt_plan IUCN Area ha Location Notes Reservation Statutory Rules Reservation auth NCA Adamsfield Conservation Area Yes - WHA Statutory VI 5,376.25 Derwent Valley Historic mining area 27-Jun-1990 1990#78 subject to PWS True 25.12.96 SR 1996 Alma Tier Conservation Area No IV 287.31 Glamorgan-Spring 03-Jan-2001 Alma Tier PWS True Bay Forest Reserve Alpha Pinnacle Conservation Area GMP - Reserve Report V 275.50 Southern Midlands Dry sclerophyll forest 24-Jul-1996 subject to 25.12.96 PWS True SR 1996 #234 Anderson Islands Conservation Area No V 749.57 Flinders 06 Apr 2011 PWS True Ansons Bay Conservation Area GMP - Reserve Report VI 104.56 Break ODay Coastal 27-May-1983 yyyy#76 PWS True Ansons River Conservation Area No VI 93.77 Ansons Bay 17-Apr-2013 SR13 of 2013 PWS True Apex Point -

Appendix 7-2 Protected Matters Search Tool (PMST) Report for the Risk EMBA

Environment plan Appendix 7-2 Protected matters search tool (PMST) report for the Risk EMBA Stromlo-1 exploration drilling program Equinor Australia B.V. Level 15 123 St Georges Terrace PERTH WA 6000 Australia February 2019 www.equinor.com.au EPBC Act Protected Matters Report This report provides general guidance on matters of national environmental significance and other matters protected by the EPBC Act in the area you have selected. Information on the coverage of this report and qualifications on data supporting this report are contained in the caveat at the end of the report. Information is available about Environment Assessments and the EPBC Act including significance guidelines, forms and application process details. Report created: 13/09/18 14:02:20 Summary Details Matters of NES Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act Extra Information Caveat Acknowledgements This map may contain data which are ©Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia), ©PSMA 2010 Coordinates Buffer: 1.0Km Summary Matters of National Environmental Significance This part of the report summarises the matters of national environmental significance that may occur in, or may relate to, the area you nominated. Further information is available in the detail part of the report, which can be accessed by scrolling or following the links below. If you are proposing to undertake an activity that may have a significant impact on one or more matters of national environmental significance then you should consider the Administrative Guidelines on Significance. World Heritage Properties: 11 National Heritage Places: 13 Wetlands of International Importance: 13 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park: None Commonwealth Marine Area: 2 Listed Threatened Ecological Communities: 14 Listed Threatened Species: 311 Listed Migratory Species: 97 Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act This part of the report summarises other matters protected under the Act that may relate to the area you nominated. -

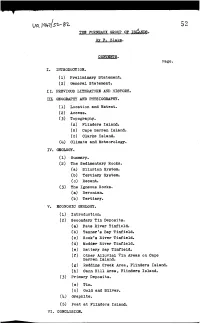

THE FURNEAUX GROUP of Istanns. by F. Blake. CONTENTS. I. INTRODUCTION. (1) Preliminary Statement. (2) General Statement. II

52 THE FURNEAUX GROUP OF IStANns. By F. Blake. CONTENTS. Page. I. INTRODUCTION. (1) Preliminary Statement. (2) General Statement. II. PREVIOUS LITERATURE AND HISTOR~. III. GEOGRAPHY AND PHYSIOGRAPHY. (1) Location and Extent. (2) Access. ( 5) Topography. (A) Flinders Island. (B) Cape Barren Island. (c) Clarke Island. (4) Climate and Meteorology. IV. GEOLOGY. (1) Summary. (2) The Sedimentary Rocks. (a) Silurian System. (b) Tertiary System. (c) Recent. (3) The Igneous Rocks. (a) Devonian. (b) Tertiary. V. ECONOMIC GEOLOGY. (1) Introduction. (2) Secondary Tin Deposits. (a) Pats River Tin:field. (b) Tanner's Bay Tin:field. (c) ROOk's River Tin:field. (d) Modder River Tin:field. (e) Battery Bay Tin:field. (f) Other Alluvial Tin Areas on Cape Barren Island. (g) Reddins Creek Area, Flinders Island. (h) Cann Hill Area, Flinders Island. (3) Primary Deposits. (a) Tin. Cb) Gold and Silver. (4) Graphite. (5) Peat at Flinders Island. VI. CONCLUSION. 53 TEE FURNEAUX GROUP OF ISLANDS I. INTRODUCTION (1) Preliminary Statement. Flinders and Cape Barren Islands have been steady, though small, contributors to the tin output of this State over a period of 45 years. During this time no outstanding mining events have taken place and the development has proved to be of slow progression. No large mines are in existence and mining generally has been confined to the winning of alluvial tin on a small scale. Flinders Island is better known for the splendid grazing areas along the west coast belt, which are so suitable for dairy-farming, and cattle and sheep raising. (2) General Statement. The field work in the Furneaux Group was carried out during the period between the 6th May and 29th June, 1935. -

Ramsar National Report to COP13

Ramsar National Report to COP13 Section 1: Institutional Information Important note: the responses below will be considered by the Ramsar Secretariat as the definitive list of your focal points, and will be used to update the information it holds. The Secretariat’s current information about your focal points is available at http://www.ramsar.org/search-contact. Name of Contracting Party The completed National Report must be accompanied by a letter in the name of the Head of Administrative Authority, confirming that this is the Contracting Party’s official submission of its COP13 National Report. It can be attached to this question using the "Manage documents" function (blue symbol below) › Australia You have attached the following documents to this answer. Ramsar_National_Report-Australia-letter_re_submission-signed-Jan_2018.docx.pdf - Letter from Head of Australia's Ramsar Administrative Authority Designated Ramsar Administrative Authority Name of Administrative Authority › Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Australian Government Department of the Environment and Energy Head of Administrative Authority - name and title › Mr Mark TaylorAssistant Secretary, Wetlands, Policy and Northern Water UseCommonwealth Environmental Water Office Mailing address › GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Telephone/Fax › +61 2 6274 1904 Email › [email protected] Designated National Focal Point for Ramsar Convention Matters Name and title › Ms Leanne WilkinsonAssistant Director, Wetlands Section Mailing address › Wetlands, Policy and -

THE TASMANIAN FRESHWATER PROJECT Freshwater Condition

THE TASMANIAN FRESHWATER PROJECT Freshwater Condition An initiative of the Tasmanian Independent Science Council Prepared by Christine Coughanowr August 2021 1 ABOUT THE TASMANIAN FRESHWATER PROJECT What’s happening with freshwater in Tasmania? What is the condition of our rivers, lakes, wetlands and estuaries? Are our water supplies clean, plentiful and well-managed? Who is minding the store and doing the maths? What are risks of getting it wrong? Tasmania prides itself on having a clean, green image, underpinned by a perception of abundant and pristine freshwater resources. A closer look suggests that many of our rivers are already under significant stress and are likely to become further damaged as climate change progresses. Added to this is the increasing demand for further extractions to support ambitious irrigation, hydropower, aquaculture, mining and other developments. Can our freshwater systems sustain this potential rate of extraction? In short - we don’t know, in part due to a lack of robust monitoring, delayed reporting, limited metering of water use, and a tendency to set ambitious growth targets without first doing the maths. Finally, current water policies and regulations do not clearly underpin sustainable use, and pricing arrangements send conflicting signals. The Tasmanian Freshwater Project is an initiative of the Tasmanian Independent Science Council. Its purpose is to provide an overview of this resource based on reports, publications and other information sources that are currently available. The Project also identifies major gaps in our understanding, raises key issues and recommends a number of actions to better conserve our freshwater systems and support sustainable use. The Tasmanian Freshwater Project is envisaged as four main review papers: • Freshwater condition • Freshwater use • Freshwater policy, planning and regulation • Freshwater economics This paper is the first to be published.