Kashering Keilim: Back to Basics Rabbi Moshe Grebenau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Separating Terumah Tameh for Tahor

בס"ד Volume 13. Issue 26 Separating Terumah Tameh for Tahor The beginning of masechet Terumot discusses separating The Tosfot (Yevamot 89a) first citesthe Rivan that cites the terumah gedolah – the first gift removed from produce and above pasuk as the source. The Tosfot reject this based on given to the kohanim. Specifically, the Mishnah begins by the Gemara cited above which explains that the cases discussing who is able to separate terumah and the manner derived from the pasuk would not be terumah at all, even in which it must be done. Many of the Mishnayot discuss be’shogeg. separating terumah from one pile or type of produce to satisfy the requirements of another. One case discussed (2:2) The Tosfot therefore brings three answer. First they cite is separating terumah from a tameh pile of produce for a Rashi who explains that the Chachamim forbad it since it tahor one. The Mishnah forbids such practice. If one would result in a loss for the Kohen. Had the person nonetheless does so, the Mishnah explains that if it was a separated from the tahor pile, the Kohen would have mistake (be’shogeg), e.g. he did not know it was tameh, then received edible produce. Since however the requirement was it is considered terumah. If however he acted deliberately, separated from tameh produce, the Kohen can only burn it then “he has done nothing”. We shall try an understand this and therefore loses out. Consequently, the Chachamim law. ideally prevented such practice. The Bartenura explains that we must understand that in this Second they suggest that perhaps the Chachamim instituted Mishnah the produce was tameh after the point it because a gezeira including these cases where there was a shaat obligated in separating maasrot. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

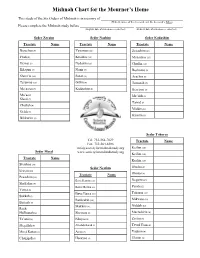

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

Of the Mishnah, Bavli & Yerushalmi

0 Learning at SVARA SVARA’s learning happens in the bet midrash, a space for study partners (chevrutas) to build a relationship with the Talmud text, with one another, and with the tradition—all in community and a queer-normative, loving culture. The learning is rigorous, yet the bet midrash environment is warm and supportive. Learning at SVARA focuses on skill-building (learning how to learn), foregrounding the radical roots of the Jewish tradition, empowering learners to become “players” in it, cultivating Talmud study as a spiritual practice, and with the ultimate goal of nurturing human beings shaped by one of the central spiritual, moral, and intellectual technologies of our tradition: Talmud Torah (the study of Torah). The SVARA method is a simple, step-by-step process in which the teacher is always an authentic co-learner with their students, teaching the Talmud not so much as a normative document prescribing specific behaviors, but as a formative document, shaping us into a certain kind of human being. We believe the Talmud itself is a handbook for how to, sometimes even radically, upgrade our tradition when it no longer functions to create the most liberatory world possible. All SVARA learning begins with the CRASH Talk. Here we lay out our philosophy of the Talmud and the rabbinic revolution that gave rise to it—along with important vocabulary and concepts for anyone learning Jewish texts. This talk is both an overview of the ultimate goals of the Jewish enterprise, as well as a crash course in halachic (Jewish legal) jurisprudence. Beyond its application to Judaism, CRASH Theory is a simple but elegant model of how all change happens—whether societal, religious, organizational, or personal. -

Judges) “In All Your Gates” That They Are to Judge the People with Righteous Judgment

בייה PORTION DATE HEB DATE TORAH NEVIIM RENEWED Shoftim 18 Aug. 2018 7 Elul 5778 Deut. 16:18-21:9 Isa. 51:12-52:12 John 14:9-20 This week’s Torah portion starts with the qualification of shoftim (judges) “in all your gates” that they are to judge the people with righteous judgment. The Torah then describes how they are to judge against the accused. The Midrash questions the eligibility of judges. The immediate family of litigants are disqualified to judge as well as they are ineligible to testify as said, “The ahvot (fathers) shall not be put to death for the children, neither shall the children be put to death for the ahvot.” (Deut. 24:16) The Gemara interprets: fathers shall not be executed because of the testimony of sons, and vice versa.1 Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel (10 BCE-70 CE) said: Do not make light of justice, for it is one of the three legs of the world: justice, truth, and on peace. Therefore, we are to be mindful of not perverting justice as “you can cause the world to shake2 for it (justice) is one of the legs of Hashem’s Throne of Glory. “Righteousness and justice are the foundation of Your throne.” (Psa 85:15) The Proverbs 6:6-8 says, “Go to the ant, you lazy one; consider her halachot, and be wise: They have no guide, overseer, or ruler, yet she; Provides her food in the and gathers her food in the harvest.” The sages teach the ants has three stories in its home. -

TISHREI Rosh Hashanah Begins on Friday Night. When

9 TISHREI The Molad: Monday night, 11:27 and 11 portions.1 The moon may be sanctified until Tuesday, the 15th, 5:49 p.m.2 The fall equinox: Thursday, Cheshvan 1, 9:00 a.m. Rosh HaShanah begins on Monday night. When lighting candles, we recite two blessings: L’hadlik ner shel Yom HaZikaron (“...to kindle the light of the Day of Remembrance”) and Shehecheyanu (“...who has granted us life...”). (In the blessing should be vocalized לזמן Shehecheyanu, the word lizman, with a chirik.) Tzedakah should be given before lighting the candles. Girls should begin lighting candles from the age when they can be trained in the observance of the mitzvah.3 Until marriage, girls should light only one candle. The Rebbe urged that all Jewish girls should light candles before Shabbos and festivals. Through the campaign mounted at his urging, Mivtza Neshek, the light of the Shabbos and the festivals has been brought to tens of thousands of Jewish homes. A man who lights candles should do so with a blessing, but should not recite the blessing Shehecheyanu.4 The Afternoon Service before Rosh HaShanah. “Regarding the issue of kavanah (intent) in prayer, for those who do not have the ability to focus their kavanah because of a lack of knowledge or due to other factors... it is sufficient that they have in mind a general intent: that their prayers be accepted before Him as if they were recited with all the intents 1. One portion equals 1/18 of a minute. 2. The times for sanctifying the moon are based on Jerusalem Standard Time. -

2 Nachal Nove'ah

2 Nachal Nove’ah - Taharot לעילוי נשמת יחזקאל זעליג בן ישראל ע"ה Nachal Nove’ah - Taharot 3 4 Nachal Nove’ah - Taharot Table of Contents EDITORS FORWARD 14 KEILIM 15 Kedushat Eretz Yisrael 15 Keilim (1:6) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier Broken Klei Cheres 17 Keilim (3:3) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier The Toy Oven 20 Keilim (5:1) Yehuda Gottlieb My Sons Have Defeated Me 23 Keilim (5:10) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier Same Action, Different Outcome 25 Keilim (8:2) Allon Ledder Metalware – Resurrecting Tumah 28 Keilim (11:1) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier Human and Animal Jewellery 31 Keilim (12:1) Alex Tsykin “Fixing” a Needle 33 Keilim (14:5) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier The Wool Comb 35 Keilim (13:8) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier Nachal Nove’ah - Taharot 5 A “Standard” Meal 38 Menachot (17:11) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier To Teach or Not To Teach 41 Keilim (17:16) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier The Impurity of Wooden Vessels 44 Keilim (18:9) Rav Yonatan Rosensweig Covered Utensils 46 Keilim (22:1) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier Three Types of Sevachot 48 Keilim (24:17) Yehuda Gottlieb Keilim - Inside and Out 50 Keilim (25:1) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier Yi’ush – Losing Hope in the Face of Theft 53 Keilim (26:7) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier Combining Different Materials 56 Keilim (27:1) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier Bigdei Aniyim 59 Keilim (29:8) Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier OHALOT 61 Tumah B’Chiburin 61 Ohalot (1:1) 61 Yisrael Yitzchak Bankier 61 6 Nachal Nove’ah - Taharot The Foot Bone’s Connected to the Leg Bone 64 Ohalot (1:8) Yehuda Gottlieb Kli Cheres in the Arubah 67 Ohalot (5:3-4) Yisrael Yitzchak -

Pesachim - Simanim ףד י ח – Daf 18 1

Pesachim - Simanim ףד י ח – Daf 18 1. A cow drinking mei chatas Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak brought a Mishnah from Parah to prove that when Rebbe Yehuda retracted his ruling and said mashkin can only be metamei mid’Rabbanon, it was not just with regard to keilim but also to .if a cow drank mei chatas its flesh is tamei – הרפ התתשש מ י תאטח הרשב אמט ,food. The Mishnah stated the water is nullified in the cow’s intestines and lost its capacity to be – לטב ו עמב י ה ,Rebbe Yehudah said metamei, therefore, the flesh, which is considered food, is tahor. Rashi explains that since the water becomes unfit for purification within the cow’s innards, it loses its capacity to be metamei. If Rebbe Yehudah held that mashkin is metamei mid’Oraysa, then the water should be metamei regardless if it is fit for mei chatas. The Gemara says that this is not a proof that Rebbe Yehuda holds mashkin are only metamei food means that it became nullified from being metamei לטב ו עמב י ה mid’Rabbanon, because it may be that , האמוט הלק meaning, that it cannot make a person or vessels tamei, but it still can be metamei , האמוט מח ו הרומ Really Rebbe Yehudah – על ו םל לטב ו מב י הע ירמגל ,such as food, and in this case flesh. Rav Ashi answered because once – שמ ו ם הד ו ה היל קשמ ה רס ו ח ,holds that the water is completely nullified in the cow’s intestines inside the cow the water is a putrid beverage, which is entirely precluded from tumah. -

Laura and Jonathan Posniak on the Birth of a Son

MIZRACHI MATTERS SHABBAT VAYETZE Friday, 27 November (11 Kislev) This week’s newsletter is sponsored in loving memory of on her Yartzeit this Shabbat by her family ע"ה Noemi Weiss Shabbat Candle Shabbat Candle Lighting: 7:00-7:05pm Lighting: 8:05pm Friday Saturday Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday 27 November 28 November 29 November 30 November 1 December 2 December 3 December 4 December 11 Kislev 12 Kislev 13 Kislev 13 Kislev 14 Kislev 15 Kislev 16 Kislev 17 Kislev 1. Beit Yehuda 2. Kehillat Ohr David 3. Beit Midrash (Beit Haroeh Shabbat Morning) 4 . Bnei Akiva 5 . Elsternwick 6 . Midrashah 7 . Goldberger Hall Dawn 4:41am 4:41am 4:41am 4:41am 4:40am 4:40am 4:40am 4:40am Tallit & Tefillin 4:52am 4:52am 4:51am 4:51am 4:50am 4:50am 4:50am 4:49am Sunrise 5:53am 5:53am 5:53am 5:53am 5:52am 5:52am 5:52am 5:52am 9:30am 9:30am 9:30am 9:30am 9:30am 9:30am 9:30am 9:31am (גר״א) Sh'ma Earliest Mincha 1:45pm 1:45pm 1:46pm 1:46pm 1:46pm 1:47pm 1:47pm 1:48pm 6:52pm 6:53pm 6:54pm 6:55pm 6:55pm 6:56pm 6:57pm 6:58pm (גר״א) Plag HaMincha Sunset 8:23pm 8:24pm 8:25pm 8:26pm 8:27pm 8:28pm 8:28pm 8:29pm Night/Shabbat Ends 9:09pm 9:10pm 9:12pm 9:13pm 9:14pm 9:15pm 9:16pm 9:17pm DAF YOMI Pesachim 6 Pesachim 7 Pesachim 8 Pesachim 9 Pesachim 10 Pesachim 11 Pesachim 12 Pesachim 13 Via Zoom 8:15am 8:45am 8:15am 8:15am 8:15am 8:15am 8:15am Rina Pushett Kew Shiur Rabbeinu Bachye Lunch and Learn “Following in the Parsha Shiur Emunah Shuir Sefer Shmuel for women R’ Danny Mirvis Footsteps of our R’ Danny Mirvis Series 6:00pm R’ Danny Mirvis 1:00pm Fathers” 8:00pm Speaker: “(Trying to) Truly 9:30am Gemara B’Iyun 11:00am Parasha Shiur SHIURIM Dr. -

Class 5 – the Talmud Rabbi Moshe Davis

Torah She’Be’Al Peh BeShanah History and Development of the Oral Tradition Class 5 – The Talmud Rabbi Moshe Davis Class Outline Review Definition of Talmud Development of the Talmud Talmudic form and style I. Review The Oral Tradition was organized/written down by Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi The Mishnah approach is fundamentally different than the Midrash approach Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi’s collection of the Oral Tradition is called the Mishnah There are additional Oral Traditions that were not incorporated into the Mishnah, which fall into two categories: Beraita/Tosephta and Midrash. Seder Masechta Perek Mishnah Six Sedarim of the Mishnah Zeraim Moed Nashim Nezikin Kodashim Tohorot Berakhot · Pe'ah · Shabbat · Eruvin · Yevamot · Bava Kamma · Zevahim · Menahot Keilim · Oholot · Demai · Kil'ayim · Pesahim · Shekalim · Ketubot · Bava Metzia · · Hullin · Bekhorot · Nega'im · Parah · Shevi'it · Terumot · Yoma · Sukkah · Nedarim · Nazir Bava Batra · Arakhin · Temurah · Tohorot · Mikva'ot Ma'aserot · Beitzah · · Sotah · Gittin · Sanhedrin · Keritot · Me'ilah · · Niddah · Ma'aser Sheni · Rosh Hashanah · Kiddushin Makkot · Shevu'ot · Tamid · Middot · Makhshirin · Zavim Hallah · Orlah · Ta'anit · Megillah · Eduyot · Kinnim · Tevul Yom · Bikkurim Mo'ed Katan · Avodah Zarah · Yadayim · Uktzim Hagigah Avot · Horayot Torah She’Be’Al Peh Beshanah – Rabbi Moshe Davis II. Definition of Talmud 1. Understanding Torah Babylonian Talmud, Avot 5:22 He [Ben Hei Hei] would also say: Five years is the age for the study of Scripture. Ten, for the study of Mishnah. Thirteen, for the obligation to observe the mitzvot. Fifteen, for the study of Talmud. Eighteen, for marriage. Twenty, to pursue [a livelihood]. Thirty, for strength, Forty, for understanding. -

Divrei Hayamim 1 11-20 Ketuvim Simchi Machshirim 4-6 Mishnah Sokol Tohorot 1-3 Mishnah Soyfer Vayechi Torah Spanganthal Tzfaniah Navi J

Abergel Miketz Torah Abraizov Devirim Torah Addi Acahrei Mos Torah Adler Tehillim 30-40 Ketuvim Akselrod Shemos Torah G.Alster Amos Navi Apter Balak Torah Aron Peah 1-4 Mishnah Ashkanazy Shlach Torah Ashkenas Peah 5-9 Mishnah Avital Terumot 1-5 Mishnah J. Bacon Negaim 1-5 Mishnah S. Bacon Negaim 6-10 Mishnah Baker Maaser Sheni Mishnah Bannett yevamot 1-6 Mishnah Barach Ki Tavo Torah Baron Bo Torah Barth D Shmini Torah Barth Bikkurim Mishnah Basis Korach Torah H.Beckoff Ekev Torah N.Beckoff Besah Mishnah L.Bien Samuel 2 14-24 Navi M. Bender Emor Torah Berger Pinchas Torah M. Berkowitz Challah Mishnah M. Berman Beshalach Torah A. Bichler Micha Navi Blatt Kedushin Mishnah A.Bloom Yirmyahu 1-10 Navi J. Bloom Moed Katan Mishnah Bluman Yevamot 7-11 Mishnah Bodner Shabbos 1-4 Mishnah Boussi Yirmyahu 11-20 Navi A.Bowski Tehillim 1-10 Ketuvim L.Bowski Samuel 1 1-10 Navi Brandes Ovadiah Navi Brandstatter Shabbos 9-13 Mishnah Bravman Taanit Mishnah Breban Rosh Hashana Mishnah Brodsky Chukat Torah Brook Vayelech Torah Caplan Reeh Torah Chait Behar Torah Cheifetz Vayechi Torah Chernela Vayikra Torah Cochin Tehillim 20-30 Ketuvim J. Cohen Yhoshua 1-12 Navi M.Cohen Noach Torah Eis Peah 5-9 Mishnah Eisenstadter Toldot Torah Epstein Lech Lecha Torah Felner Nitzavim Torah Fialkoff Vayelech Torah Fischer Nazir Mishnah Fishman Challah Mishnah Fishweicher Maasarot Mishnah Moshe Fishweicher Matot Torah Fleisher Vayetzei Torah Fleyshmakher Ki Tetzei Torah Fogelman Chagiga Mishnah Fox Esther Navi Frank shabbos 8-12 Mishnah D. Friedman Keilim Mishnah Y.Friedman Gitten1-5 Mishnah Michael Friedman Shoftim Torah Mikki Friedman Shoftim 1-12 Navi Frohlich Yoma 1-4 Mishnah Gabovich Tehillim 31-40 Ketuvim Galitsky Tehillim 41-50 Ketuvim Gandelman Bamidbar Torah Gans Yevamot 12-16 Mishnah Garber Terumot 6-11 Mishnah Garfunkel Samuel 1 1-12 Navi Gelerter Behar Ketuvim Gensler Terumah Torah Gerber Shoftim 12-21 Navi Gershon Ketuvos 1-7 Mishnah Gerstley Pesachim 1-4 Mishnah Gitlin Vayeyra Torah Glass Sukkah Mishnah Glassman tehillim 51-60 Torah H.Gold Noach Ketuvim A.