Fungal Endophytes As Efficient Sources of Plant-Derived Bioactive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fungal Endophytes from the Aerial Tissues of Important Tropical Forage Grasses Brachiaria Spp

University of Kentucky UKnowledge International Grassland Congress Proceedings XXIII International Grassland Congress Fungal Endophytes from the Aerial Tissues of Important Tropical Forage Grasses Brachiaria spp. in Kenya Sita R. Ghimire International Livestock Research Institute, Kenya Joyce Njuguna International Livestock Research Institute, Kenya Leah Kago International Livestock Research Institute, Kenya Monday Ahonsi International Livestock Research Institute, Kenya Donald Njarui Kenya Agricultural & Livestock Research Organization, Kenya Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/igc Part of the Plant Sciences Commons, and the Soil Science Commons This document is available at https://uknowledge.uky.edu/igc/23/2-2-1/6 The XXIII International Grassland Congress (Sustainable use of Grassland Resources for Forage Production, Biodiversity and Environmental Protection) took place in New Delhi, India from November 20 through November 24, 2015. Proceedings Editors: M. M. Roy, D. R. Malaviya, V. K. Yadav, Tejveer Singh, R. P. Sah, D. Vijay, and A. Radhakrishna Published by Range Management Society of India This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Plant and Soil Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Grassland Congress Proceedings by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paper ID: 435 Theme: 2. Grassland production and utilization Sub-theme: 2.2. Integration of plant protection to optimise production -

Pro-Oxidizing Metabolic Weapons ☆ ⁎ Etelvino J.H

Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part C 146 (2007) 88–110 www.elsevier.com/locate/cbpc Review The dual face of endogenous α-aminoketones: Pro-oxidizing metabolic weapons ☆ ⁎ Etelvino J.H. Bechara a, , Fernando Dutra b, Vanessa E.S. Cardoso a, Adriano Sartori a, Kelly P.K. Olympio c, Carlos A.A. Penatti d, Avishek Adhikari e, Nilson A. Assunção a a Departamento de Bioquímica, Instituto de Química, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. Prof. Lineu Prestes 748, 05508-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil b Centro de Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, Universidade Cruzeiro do Sul, São Paulo, SP, Brazil c Faculdade de Saúde Pública, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil d Department of Physiology, Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH, USA e Department of Biological Sciences, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA Received 31 January 2006; received in revised form 26 June 2006; accepted 6 July 2006 Available online 14 July 2006 Abstract Amino metabolites with potential prooxidant properties, particularly α-aminocarbonyls, are the focus of this review. Among them we emphasize 5-aminolevulinic acid (a heme precursor formed from succinyl–CoA and glycine), aminoacetone (a threonine and glycine metabolite), and hexosamines and hexosimines, formed by Schiff condensation of hexoses with basic amino acid residues of proteins. All these metabolites were shown, in vitro, to undergo enolization and subsequent aerobic oxidation, yielding oxyradicals and highly cyto- and genotoxic α-oxoaldehydes. Their metabolic roles in health and disease are examined here and compared in humans and experimental animals, including rats, quail, and octopus. In the past two decades, we have concentrated on two endogenous α-aminoketones: (i) 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), accumulated in acquired (e.g., lead poisoning) and inborn (e.g., intermittent acute porphyria) porphyric disorders, and (ii) aminoacetone (AA), putatively overproduced in diabetes mellitus and cri-du-chat syndrome. -

Monocyclic Phenolic Acids; Hydroxy- and Polyhydroxybenzoic Acids: Occurrence and Recent Bioactivity Studies

Molecules 2010, 15, 7985-8005; doi:10.3390/molecules15117985 OPEN ACCESS molecules ISSN 1420-3049 www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules Review Monocyclic Phenolic Acids; Hydroxy- and Polyhydroxybenzoic Acids: Occurrence and Recent Bioactivity Studies Shahriar Khadem * and Robin J. Marles Natural Health Products Directorate, Health Products and Food Branch, Health Canada, 2936 Baseline Road, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0K9, Canada * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-613-954-7526; Fax: +1-613-954-1617. Received: 19 October 2010; in revised form: 3 November 2010 / Accepted: 4 November 2010 / Published: 8 November 2010 Abstract: Among the wide diversity of naturally occurring phenolic acids, at least 30 hydroxy- and polyhydroxybenzoic acids have been reported in the last 10 years to have biological activities. The chemical structures, natural occurrence throughout the plant, algal, bacterial, fungal and animal kingdoms, and recently described bioactivities of these phenolic and polyphenolic acids are reviewed to illustrate their wide distribution, biological and ecological importance, and potential as new leads for the development of pharmaceutical and agricultural products to improve human health and nutrition. Keywords: polyphenols; phenolic acids; hydroxybenzoic acids; natural occurrence; bioactivities 1. Introduction Phenolic compounds exist in most plant tissues as secondary metabolites, i.e. they are not essential for growth, development or reproduction but may play roles as antioxidants and in interactions between the plant and its biological environment. Phenolics are also important components of the human diet due to their potential antioxidant activity [1], their capacity to diminish oxidative stress- induced tissue damage resulted from chronic diseases [2], and their potentially important properties such as anticancer activities [3-5]. -

Multiple Low-Dose Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes in the Mouse

Multiple low-dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes in the mouse. Evidence for stimulation of a cytotoxic cellular immune response against an insulin-producing beta cell line. R C McEvoy, … , S Sandler, C Hellerström J Clin Invest. 1984;74(3):715-722. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI111487. Research Article Mice were examined for the presence of splenocytes specifically cytotoxic for a rat insulinoma cell line (RIN) during the induction of diabetes by streptozotocin (SZ) in multiple low doses (Multi-Strep). Cytotoxicity was quantitated by the release of 51Cr from damaged cells. A low but statistically significant level of cytolysis (5%) by splenocytes was first detectable on day 8 after the first dose of SZ. The cytotoxicity reached a maximum of approximately 9% on day 10 and slowly decreased thereafter, becoming undetectable 42 d after SZ was first given. The time course of the in vitro cytotoxic response correlated with the degree of insulitis demonstrable in the pancreata of the Multi-Strep mice. The degree of cytotoxicity after Multi-Strep was related to the number of effector splenocytes to which the target RIN cells were exposed and was comparable to that detectable after immunization by intraperitoneal injection of RIN cells in normal mice. The cytotoxicity was specific for insulin-producing cells; syngeneic, allogeneic, and xenogeneic lymphocytes and lymphoblasts, 3T3 cells, and a human keratinocyte cell line were not specifically lysed by the splenocytes of the Multi- Strep mice. This phenomenon was limited to the Multi-Strep mice. Splenocytes from mice made diabetic by a single, high dose of SZ exhibited a very low level of cytotoxicity against the RIN cells. -

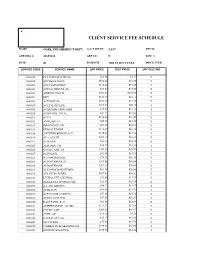

Oakland Sheriff's Dept Fee Schedule 02.09

CLIENT SERVICE FEE SCHEDULE NAME: OAKLAND SHERIFF'S DEPT ACCT SETUP: 2/1/87 REP ID: GRP BILL #: 22857610 GRP CD: N DISC %: FS ID: 01 FS DESCR: 2003 CLIENT FEES PRICE TYPE: SERVICE CODE SERVICE NAME UPF PRICE TEST PRICE UPF DISC IND 0000018 PLT SODIUM CITRATE $12.86 $4.37 Y 0000022 APC RESISTANCE $101.62 $34.55 Y 0000201 ACETAMINOPHEN $110.24 $37.48 Y 0000202 ACETALDEHYDE (B) $73.00 $73.00 N 0000203 ARSENIC,TISSUE $302.00 $302.00 N 0000204 DHT $182.70 $62.12 Y 0000205 ACETONE (B) $102.20 $34.75 Y 0000206 ACETYLCHOLINE $165.00 $56.10 Y 0000208 ACID PHOS, PROS, IMM $35.60 $12.10 Y 0000210 ACID PHOS, TOTAL $37.22 $12.65 Y 0000211 ACTH $110.00 $37.40 Y 0000212 AMYLASE (U) $45.45 $15.45 Y 0000213 IMMUNOFIX, UR $67.39 $22.91 Y 0000214 ETHOSUXIMIDE $112.07 $38.10 Y 0000216 ANTITHROMBIN III ACT $170.46 $57.96 Y 0000219 ALA, QUANT $107.10 $36.41 Y 0000223 ALBUMIN $22.88 $22.88 N 0000224 ALBUMIN, CSF $36.25 $12.33 Y 0000225 CYCLIC AMP, UR $205.80 $69.97 Y 0000227 ALDOLASE $32.08 $10.91 Y 0000228 A-2-MACROGLOB. $78.75 $26.78 Y 0000229 ALDOSTERONE (U) $251.58 $85.54 Y 0000230 ALDOSTERONE $207.10 $70.41 Y 0000231 ALK PHOS ISOENZYMES $61.34 $20.86 Y 0000232 AFP, FLUID W/RFX $107.40 $36.52 Y 0000233 LEUKOCYTE ALK PHOS $34.60 $11.76 Y 0000234 ALKALINE PHOSPHATASE $22.88 $22.88 N 0000235 A-1-ANTITRYPSN $40.22 $13.67 Y 0000236 AMIKACIN $99.91 $33.97 Y 0000237 AFP,TUMOR (CHIRON) $53.86 $18.31 Y 0000238 AMINO ACID SCR $87.15 $29.63 Y 0000240 RAST PANEL #103 $62.00 $62.00 N 0000241 AMPHETAMINE GC/MS $111.70 $37.98 Y 0000242 CYCLIC AMP $205.80 $69.97 Y 0000243 AMYLASE $16.42 $5.58 Y 0000248 HACKBERRY IGE $35.40 $35.40 N 0000249 ANA W/RFX $55.00 $18.70 Y 0000250 *AMIKACIN,PEAK&TROUGH $199.83 $67.94 Y 0000251 ANDROSTENEDIONE $180.65 $61.42 Y 0000252 ANTI-DIUR. -

7Th International Conference on Countercurrent Chromatography, Hangzhou, August 6-8, 2012 Program

010 7th international conference on countercurrent chromatography, Hangzhou, August 6-8, 2012 Program January, August 6, 2012 8:30 – 9:00 Registration 9:00 – 9:10 Opening CCC 2012 Chairman: Prof. Qizhen Du 9:10 – 9:20 Welcome speech from the director of Zhejiang Gongshang University Session 1 – CCC Keynotes Chirman: Prof. Guoan Luo pH-zone-refining countercurrent chromatography : USA 09:20-09:50 Ito, Y. Origin, mechanism, procedure and applications K-1 Sutherland, I.*; Hewitson. P.; Scalable technology for the extraction of UK 09:50-10:20 Janaway, L.; Wood, P; pharmaceuticals (STEP): Outcomes from a year Ignatova, S. collaborative researchprogramme K-2 10:20-11:00 Tea Break with Poster & Exhibition session 1 France 11:00-11:30 Berthod, A. Terminology for countercurrent chromatography K-3 API recovery from pharmaceutical waste streams by high performance countercurrent UK 11:30-12:00 Ignatova, S.*; Sutherland, I. chromatography and intermittent countercurrent K-4 extraction 12:00-13:30 Lunch break 7th international conference on countercurrent chromatography, Hangzhou, August 6-8, 2012 January, August 6, 2012 Session 2 – CCC Instrumentation I Chirman: Prof. Ian Sutherland Pro, S.; Burdick, T.; Pro, L.; Friedl, W.; Novak, N.; Qiu, A new generation of countercurrent separation USA 13:30-14:00 F.; McAlpine, J.B., J. Brent technology O-1 Friesen, J.B.; Pauli, G.F.* Berthod, A.*; Faure, K.; A small volume hydrostatic CCC column for France 14:00-14:20 Meucci, J.; Mekaoui, N. full and quick solvent selection O-2 Construction of a HSCCC apparatus with Du, Q.B.; Jiang, H.; Yin, J.; column capacity of 12 or 15 liters and its China Xu, Y.; Du, W.; Li, B.; Du, application as flash countercurrent 14:20-14:40 O-3 Q.* chromatography in quick preparation of (-)-epicatechin 14:40-15:30 Tea Break with Poster & Exhibition session 2 Session 3 – CCC Instrumentation II Chirman: Prof. -

The Instructional Design of Ethnoscience-Based Inquiry

Journal for the Education of Gifted Young Scientists, 8(4), 1493-1507, Dec 2020 e-ISSN: 2149- 360X youngwisepub.com jegys.org © 2020 Research Article The instructional design of ethnoscience-based inquiry learning for scientific explanation about Taxus sumatrana as cancer medication Sudarmin S.1, Diliarosta Skunda2, Sri Endang Pujiastuti3, Sri Jumini4*, Agung Tri Prasetya5 Departement of Physics Education Program, Universitas Sains Al-Qur’an, Indonesia Article Info Abstract Received: 09 August 2020 The ethnoscience approach is carried out by integrating local wisdom culture in science Revised: 23 November 2020 learning. The Minang community believes that the Taxus sumatrana plant is a cancer drug. Accepted: 07 December 2020 But they have not been able to explain its benefits conceptually based on scientific inquiry Available online: 15 December 2020 with relevant references. This study aims to solve these problems through (1) designing Keywords: ethnoscience-based inquiry learning to study the bioactivity of Taxus sumatrana; and (2) Cancer medication describe scientific experiments on plants as cancer drugs. This research includes Ethnoscience-based inquiry learning qualitative research to reconstruct scientific explanations based on local wisdom. The Instructional design data were obtained through observations at the research location regarding community Scientific explanation local wisdom and laboratory activities including isolation, phytochemical identification, Taxus sumatrana and chemical structure testing using Perkin Elmer 100 -

Application of Cornelian Cherry Iridoid-Polyphenolic Fraction and Loganic Acid to Reduce Intraocular Pressure

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2015, Article ID 939402, 8 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/939402 Research Article Application of Cornelian Cherry Iridoid-Polyphenolic Fraction and Loganic Acid to Reduce Intraocular Pressure Dorota Szumny,1,2 Tomasz SozaNski,1 Alicja Z. Kucharska,3 Wojciech Dziewiszek,1 Narcyz Piórecki,4,5 Jan Magdalan,1 Ewa Chlebda-Sieragowska,1 Robert Kupczynski,6 Adam Szeldg,1 and Antoni Szumny7 1 Department of Pharmacology, Wrocław Medical University, 50-345 Wrocław, Poland 2Ophthalmology Clinic, Uniwersytecki Szpital Kliniczny, 50-556 Wrocław, Poland 3Department of Fruit and Vegetables Technology, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, 51-630 Wrocław, Poland 4Arboretum and Institute of Physiography in Bolestraszyce, 37-722 Bolestraszyce, Poland 5Department of Turism & Recreation, University of Rzeszow, 35-959 Rzeszow,´ Poland 6Department of Environment Hygiene and Animal Welfare, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, 51-630 Wrocław, Poland 7Department of Chemistry, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Science, 50-375 Wrocław, Poland Correspondence should be addressed to Dorota Szumny; [email protected] Received 6 February 2015; Revised 21 April 2015; Accepted 12 May 2015 Academic Editor: MinKyun Na Copyright © 2015 Dorota Szumny et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. One of the most common diseases of old age in modern societies is glaucoma. It is strongly connected with increased intraocular pressure (IOP) and could permanently damage vision in the affected eye. As there are only a limited number of chemical compounds that can decrease IOP as well as blood flow in eye vessels, the up-to-date investigation of new molecules is important. -

Antibacterial Activities of Crude Secondary Metabolite Extracts From

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Antibacterial Activities of Crude Secondary Metabolite Extracts from Pantoea Species Obtained from the Stem of Solanum mauritianum and Their Effects on Two Cancer Cell Lines Nkemdinma Uche-Okereafor 1,*, Tendani Sebola 1, Kudzanai Tapfuma 1 , Lukhanyo Mekuto 2, Ezekiel Green 1 and Vuyo Mavumengwana 3,* 1 Department of Biotechnology and Food Technology, Faculty of Science, University of Johannesburg, PO Box 17011, Doornfontein, Johannesburg 2028, South Africa; [email protected]; (T.S.); [email protected] (K.T.); [email protected] (E.G.) 2 Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of Johannesburg, PO Box 17011, Doornfontein, Johannesburg 2028, South Africa; [email protected] 3 South African Medical Research Council Centre for Tuberculosis Research, Division of Molecular Biology and Human Genetics, Department of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Tygerberg 7505, South Africa * Correspondence: [email protected] (N.U.); [email protected] (V.M.); Tel: +27-83-974-3907 (N.U.); +27-21-938-9952 (V.M.) Received: 17 January 2019; Accepted: 14 February 2019; Published: 19 February 2019 Abstract: Endophytes are microorganisms that are perceived as non-pathogenic symbionts found inside plants since they cause no symptoms of disease on the host plant. Soil conditions and geography among other factors contribute to the type(s) of endophytes isolated from plants. Our research interest is the antibacterial activity of secondary metabolite crude extracts from the medicinal plant Solanum mauritianum and its bacterial endophytes. Fresh, healthy stems of S. mauritianum were collected, washed, surface sterilized, macerated in PBS, inoculated in the nutrient agar plates, and incubated for 5 days at 30 ◦C. -

Importance of the 4-Substituted Resorcinol Moiety

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Urolithin and Reduced Urolithin Derivatives as Potent Inhibitors of Tyrosinase and Melanogenesis: Importance of the 4-Substituted Resorcinol Moiety Sanggwon Lee 1,†, Heejeong Choi 1,† , Yujin Park 1, Hee Jin Jung 1 , Sultan Ullah 2, Inkyu Choi 1, Dongwan Kang 1, Chaeun Park 1, Il Young Ryu 1, Yeongmu Jeong 1, YeJi Hwang 1, Sojeong Hong 1, Pusoon Chun 3 and Hyung Ryong Moon 1,* 1 College of Pharmacy, Pusan National University, Busan 46241, Korea; [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (H.C.); [email protected] (Y.P.); [email protected] (H.J.J.); [email protected] (I.C.); [email protected] (D.K.); [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (I.Y.R.); [email protected] (Y.J.); [email protected] (Y.H.); [email protected] (S.H.) 2 Department of Molecular Medicine, The Scripps Research Institute, Jupiter, FL 33458, USA; [email protected] 3 College of Pharmacy and Inje Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Inje University, Gimhae 50834, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-51-510-2815; Fax: +82-51-513-6754 † These authors (S. Lee and H. Choi) contributed equally to this work. Abstract: We previously reported (E)-β-phenyl-α,β-unsaturated carbonyl scaffold ((E)-PUSC) played an important role in showing high tyrosinase inhibitory activity and that derivatives with a 4- Citation: Lee, S.; Choi, H.; Park, Y.; substituted resorcinol moiety as the β-phenyl group of the scaffold resulted in the greatest tyrosinase Jung, H.J.; Ullah, S.; Choi, I.; Kang, D.; inhibitory activity. -

Cop13 Analyses Cover 29 Jul 04.Qxd

IUCN/TRAFFIC Analyses of the Proposals to Amend the CITES Appendices at the 13th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties Bangkok, Thailand 2-14 October 2004 Prepared by IUCN Species Survival Commission and TRAFFIC Production of the 2004 IUCN/TRAFFIC Analyses of the Proposals to Amend the CITES Appendices was made possible through the support of: The Commission of the European Union Canadian Wildlife Service Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, Department for Nature, the Netherlands Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, Germany Federal Veterinary Office, Switzerland Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Dirección General para la Biodiversidad (Spain) Ministère de l'écologie et du développement durable, Direction de la nature et des paysages (France) IUCN-The World Conservation Union IUCN-The World Conservation Union brings together states, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a unique global partnership - over 1 000 members in some 140 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. IUCN builds on the strengths of its members, networks and partners to enhance their capacity and to support global alliances to safeguard natural resources at local, regional and global levels. The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions. With 8 000 scientists, field researchers, government officials and conservation leaders, the SSC membership is an unmatched source of information about biodiversity conservation. SSC members provide technical and scientific advice to conservation activities throughout the world and to governments, international conventions and conservation organizations. -

Xanthones. Part I V.* a New Synthesis of Hydroxyxanthones and Hydrozybenzophenones

3982 Grover, Shah, agad Shah : Xanthones. Part I V.* A New Synthesis of Hydroxyxanthones and Hydrozybenzophenones. By P. I<. GROVER,G. D. SHAH,and R. C. SHAH. [Reprint Order No. 6470.1 Hydroxy-santhones and -benzophenones are conveniently obtained from hydroxybenzoic acids and phenols in presence of zinc chloride and phosphorus oxychloride. DISTILLATIONof a mixture of a phenol, a phenolic acid, and acetic anhydride is the earliest and simplest method for the synthesis of hydroxyxanthones (Michael, Amer. Chsm. J., 1883, 5, 81; Kostanecki and his co-workers, Ber., 1891, 24, 1896, 3981, etc.; Lund, Robertson, and Whalley, J., 1953, 2438), but yields are often poor, experimental conditions are rather drastic, and there is a possibility of decarboxylation, autocondensation, and other side reactions (Lespegnol, Bertrand, and Dupas, BUZZ. SOC.chim. France, 1939, 6, 1925; Lund et aZ., Zoc. cit.). There are numerous other routes, but none is of general application and some require uncommon starting materials or involve a number of steps. In continuation of the work on naturally occurring xanthones (J. Indian Chem. SOC., 1953,30,457,463; J. Sci. Id.Res., India, 1954,13, B, 175; 1955,14, B, 153) the known methods for the synthesis of 1 : 3 : 7 : 8-tetrahydroxyxanthone or its tetramethyl ether * Part 111, J. Sci. Ind. Res., India, 1954, 13, B, 175. [ 19551 Xanthones. Part IV. 3953 were found unsuitable. Condensation under mild conditions of a phenolcarboxylic acid with a reactive phenol in presence of condensing agents such as anhydrous aluminium chloride, phosphorus oxychloride, phosphoric oxide, or sulphuric acid was not promising ; but a mixture of phosphorus oxychloride and fused zinc chloride, which had previously been found effective for the preparation of 2 : 4dihydroxybenzophenone (Shah and Mehta, J.