MNREGA-Participants in Wayanad, Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

Indian Workshop on Rice Kumbalanghi, Keralam December 9 -11, 2004 Organised By

Indian Workshop on Rice Kumbalanghi, Keralam December 9 -11, 2004 organised by With the Support of Thanal, L-14, Jawahar Nagar, Kawdiar P.O. Thiruvananthapuram, Keralam. India - 695 003 Tel / Fax: +91- 471-2727150. E-mail: [email protected] International Year of Rice Year International www.thanal.org Kumbalanghi Declaration On Sustaining Rice Declaration from the “Indian Workshop on Rice” December 9-11, 2004 In the Second International Year of Rice, 2004, we, the participants representing 57 organisations, primarily from rice growing states of India, working on sustainable ways of farming, environment, policy, consumer rights, farm labour having come together on a discussion on rice as part of our culture, as a basis for food security, and as a community heritage and having deliberated on the traditional practices of rice cultivation, problems facing its sustenance and the various initiatives in sustaining rice hereby recognize that 1. Genetically modified rice and lab-hybrid rice have no role in ensuring food security and sustaining rice in the country. On the contrary these are known to threaten the food sovereignty of the farmer community. 2. The green revolution has resulted in the destruction of agriculture and rural communities and has miserably failed in providing sufficient safe food and dignity of life. 3. Given the declining yields and harmful effects on human beings, plants, animals and environment health and the heavy losses to farmers, the dependence on chemical inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides should be phased out. Moreover, it is now proven beyond doubt that to ensure safe food and to sustain rice, pesticides are not required. -

Tribal Settlement in Wayanad, Kerala

International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET) Volume 8, Issue 5, May 2017, pp. 1316–1327, Article ID: IJCIET_08_05_140 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJCIET?Volume=8&Issue=5 ISSN Print: 0976-6308 and ISSN Online: 0976-6316 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed TRIBAL SETTLEMENT IN WAYANAD, KERALA Vaisakh B 4th Year B.Arch. Student, Lovely School of Architecture and Design, Lovely Professional University, Punjab. Sarita Sood Assistant Professor, Lovely School of Architecture and Design, Lovely Professional University, Punjab. ABSTRACT The tribal population in India, though a numerically small minority, represents an enormous diversity of groups. They vary among themselves in respect of language and linguistic traits, ecological settings in which they live, physical features, size of the population, the extent of acculturation, dominant modes of making a livelihood, level of development and social stratification. They are also spread over the length and breadth of the country though their geographical distribution is far from uniform. Kerala holds a unique position in the tribal map of India.[1] Mainly five tribal communities have their origin in Wayanad. The Paniya tribe is numerically the largest among them. They are the largest scheduled tribes of Kerala also. (fig.1)They are mainly settled in Wayanad. (fig.2) The majority of the Paniya tribal population (71.95%) are found in Wayanad. Taking into account the various socio -economic indicators, Paniya tribe can be considered to be a better representation of the tribal population of Kerala. This study includes the importance of tribals in Wayanad, their sustainable way of life and the relationship between settlement and environment in tribal habitat. -

Tudies, Trends & Practices May 2018, Vol

MIER Journal of Educational Studies, Trends & Practices May 2018, Vol. 8, No. 1 pp. 113 - 120 TUDI- A SAGA OF EDUCATIONAL EMPOWERMENT Sanil Mathew Mayilkunnel and Dipal Patel Shah Education is one of the most important means of upward mobility for the tribals. This is a research narrative on how an NGO, named TUDI (Tribal Unity for Development Initiative) achieved phenomenal results in a period of two decades among the group of tribals called the Paniyars in the Wayanad district of Kerala, India. The systematic and consistent efforts of TUDI at the integral development of the tribals, with great emphasis on empowering them through education, have born rich dividends. This study explores how TUDI was instrumental in bringing out many graduates, post graduates and government and other employees in just 20 years from a community whose children hardly progressed beyond the primary school level two decades ago. KEYWORDS: Tribals, TUDI, Paniyars, Education, Empowerment, Integral development INTRODUCTION Tribals are the indigenous people of India. They have their unique personality, life style, culture, and ethnic knowledge systems handed down the generations over many centuries. Paniyars are a typical tribal group in Kerala who are mostly found in the northern district of Wayanad. They normally stay in colonies and keep their customs and practices among themselves. The fact that they used to live in colonies and in a joint family system could be inferred from the statistics presented in the Logan's Manual. Logan (2000) states that according to the 1881 census, the average number of people living in a family was the highest in Wayanad (10.1). -

„Rediscovering Jain Tradition in Wayanad‟

„REDISCOVERING JAIN TRADITION IN WAYANAD‟ MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT IN HISTORY SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION 2014-15 SASI C T (PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR) DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY GOVT COLLEGE, KALPETTA WAYANAD, KERALA - 673121 CONTENT Page No. 1. Declaration 2. Certificate 3. Acknowledgement 4. Preface, Objectives, Methodology 5. Literature Review i-iv 6. Chapter 1 1-5 7. Chapter 2 6-9 8. Chapter 3 10-12 9. Chapter 4 13-22 10 Chapter 5 23-27 11 Chapter 6 28-31 12 Chapter 7 32-34 13 Appendices 35-37 14 Table 38-41 15 Images 42-56 16 Select Bibliography 57-59 (A video graphic representation on the Jain temples is attached separately in a DVD) DECLARATION I, Sasi C.T, Principal Investigator, (Assistant Professor, Department Of History, Govt College, Kalpetta, Wayanad, Kerala) do here by declare that, this is a bona fide work by me, and that it was undertaken as a Minor Research Project funded by the University Grants Commission during the period 2014-15. Kalpetta 22/9/2015 SASI C T CERTIFICATE Govt College Kalpetta, Wayanad Kerala This is to certify that this Minor Research Project entitled „REDISCOVERING JAIN TRADITION IN WAYANAD‟, submitted to the University Grants Commission is a Minor research work carried out by Sasi C T, Assistant Professor, Department of History, Govt.College, Kalpetta. No part of this work has been submitted before. Kalpetta 22/9/2015 Principal ACKNOWLEDGEMENT For doing the Minor Research Project on „Rediscovering Jain traditions in Wayanad‟ I am owed much to the assistance of distinguished personalities and institutions. I am expressing my sincere thanks to the Librarians of different Libraries. -

Know-More-About-Wayanad.Pdf

Imagine a land blessed by the golden hand of history, shrouded in the timeless mists of mystery, and flawlessly Wayanad adorned in nature’s everlasting splendor. Wayanad, with her enchanting vistas and captivating Way beyond… secrets, is a land without equal. And in her embrace you will discover something way beyond anything you have ever encountered. 02 03 INDEX Over the hills and far away…....... 06 Footprints in the sands of time… 12 Two eyes on the horizon…........... 44 Untamed and untouched…........... 64 The land and its people…............. 76 04 05 OVER THE ayanad is a district located in the north- east of the Indian state of Kerala, in the southernmost tip of the WDeccan Plateau. The literal translation of “Wayanad” is HILLS AND “Wayal-nad” or “The Land of Paddy Fields”. It is well known for its dense virgin forests, majestic hills, flourishing plantations and a long standing spice trade. Wayanad’s cool highland climate is often accompanied by sudden outbursts of torrential rain and rousing mists that blanket the landscape. It is set high on the majestic Western Ghats with altitudes FAR AWAY… ranging from 700 to 2100 m. Lakkidi View Point 06 07 Wayanad also played a prominent role district and North Wayanad remained The primary access to Wayanad is the Thamarassery Churam (Ghat Pass) in the history of the subcontinent. It with Kannur. By amalgamating North infamous Thamarassery Churam, which is often called the spice garden of the Wayanad and South Wayanad, the is a formidable experience in itself. The south, the land of paddy fields, and present Wayanad district came into official name of this highland passage is the home of the monsoons. -

!Ncredible Kerala? a Political Ecological Analysis of Organic Agriculture in the “Model for Development”

!ncredible Kerala? A Political Ecological Analysis of Organic Agriculture in the “Model for Development” By: Sapna Elizabeth Thottathil A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jake Kosek, Chair Professor Michael Watts Professor Nancy Peluso Fall 2012 ABSTRACT !ncredible Kerala? A Political Ecological Analysis of Organic Agriculture in the “Model for Development” By Sapna Elizabeth Thottathil Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Jake Kosek, Chair In 2010, the South Indian state of Kerala’s Communist-led coalition government, the Left Democratic Front (LDF), unveiled a policy to convert the entirety of the state to organic farming within ten years; some estimates claim that approximately 9,000 farmers were already participating in certified organic agriculture for export at the time of the announcement. Kerala is oftentimes hailed as a “model for development” by development practitioners and environmentalists because of such progressive environmental politics (e.g., McKibben 1998). Recent scholarship from Political Ecology, however, has christened organic farming as a neoliberal project, and much like globalized, conventional agriculture (e.g., Guthman 2007 and Raynolds 2004). Drawing from fourteen months of fieldwork in Kerala between 2009-2011, I explore this tension between Kerala as a progressive, political “model,” and globalized, corporatized organic agriculture. I utilize Kerala’s experiences with organic farming to present another story about North-South relations in globalized organic farming. In contrast to recent Political Ecological work surrounding alternative food systems, I contend that organic agriculture can actually offer meaningful possibilities for transforming the global agricultural system in local places. -

'Paniya' Tribes in Wayanad, Kerala, India 1

Running Head: AN ALTERNATIVE BLUE PRINT, A WHITE PAPER FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE ‘PANIYA’ TRIBES IN WAYANAD, KERALA, INDIA 1 JOSEPH ATHRASHAERY ULAHANNAN AN ALTERNATIVE BLUE PRINT, A WHITE PAPER FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE ‘PANIYA’ TRIBES IN WAYANAD, KERALA, INDIA VANCOUVER ISLAND UNIVERSITY MEDL 550 AN ALTERNATIVE BLUE PRINT, A WHITE PAPER FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE ‘PANIYA’ TRIBES IN WAYANAD, KERALA, INDIA 2 Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my only daughter, Angeline Rose Joe. Your smile continues to inspire my quest for knowledge. This critical step of my life would not have been possible without the support of my teachers and friends who helped me and guided me in the entire process of writing the thesis. AN ALTERNATIVE BLUE PRINT, A WHITE PAPER FOR THE EDUCATION OF THE ‘PANIYA’ TRIBES IN WAYANAD, KERALA, INDIA 3 Acknowledgements Writing a thesis has been a process that has provided me with many challenges over the past two years, primarily because, although rewarding, it has been a time- consuming project. I have spent many months away from my family and have sacrificed my time with them and with other friends with hobbies and in attending various events. Nonetheless, it has been a worthwhile and rewarding experience. The time spent will not go in vain and will assist me in my professional goals. I hope also that this research will be of use to those who inspired it and participated in it. Thank you to my supervisor at Vancouver Island University, Dr. Nadine Cruickshanks, for her time and effort in guiding me to find a research topic that proved to be a worthwhile study. -

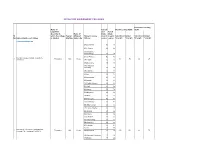

1981 Census Handbook- Wayanad District

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1981 SERIES 10 KERALA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK WAY ANAD DISTRICT PART XllI-A&B VILLAGE DIRECTORY AND TOWN DIRECTORY PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT M. VIJAYANUNNI OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICB DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA lL6f529-1 1981 CENSUS PUBUCATION .PROGRAMME KERALA STATE raper/Part number Title and subjn:t malter Paper I of 1981 Provisional Population Totah Paper 2 of 1981 Rural-urban Composition (Provisional Totals) Workers and Non-"vorkers(Provisional Totals) Disabled persons Paper 3 of 1981 Final Population Totals Paper 4 of 1981 Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Paper;) of 1981 Final Totals of workers and non-workers Part I Administration Report-Enumeration and Tabulation-(Not for sale), (for office use only) Part II-A General Population Tables (:\-series-Tables A-I to ~\-5), Part II-B Primary Census Abstract Part Ill-A and B(i) General Economic Tables (B-Sel"ies-~Tahles B-1 to B-3 and B-ll to :8-17) Part III-A and B (ii) General Economic Tables (B-Series-Table B-18 to B-20) Part III-A and B(iii) General Economic Tables (B Series-Tables B-21-B-22) Part IV-A Social and Cultural Tables (C-Series-Tables C-l to C-6) Part V-A and B Migration Tables (D-Series-Tables D-l to D-8, D-13 and D-15) Part VI-A and B Fertility Tables (F-Series-Tables F-l to F-27) Part vn Houses and Disabled population--Report and Tables (H-Series-Tables H-I and H-2) Part VIII-A and B Household Tables (HH-Series-Tables HH-l to HH-9, HH-ll, HH-12 and lHH-l7) Part IX Special Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribe;; (SC-Series-Tables SC-l to SC-6; ST-Se;i,~~:-e!-l to ST-9) ~/ if,' q.. -

Small Coffee Growers of Sulthan Bathery, Wayanad

Small Coffee Growers of Sulthan Bathery, Wayanad C.V Joy Discussion Paper No. 83 Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development Centre for Development Studies Thiruvananthapuram Small Coffee Growers of Sulthan Bathery, Wayanad C.V Joy English Discussion Paper Rights reserved First published 2004 Editorial Board: Prof. P. R. Gopinathan Nair, H. Shaji Printed at: Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development Published by: Dr K. N. Nair, Programme Co-ordinator, Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development, Centre for Development Studies, Prasanth Nagar, Ulloor, Thiruvananthapuram Cover Design: Defacto Creations ISBN No: 81-87621-86-9 Price: Rs 40 US$ 5 KRPLLD 2004 0500 ENG 2 Contents 1. Introduction 5 2. Objectives and Method 10 3. Coffee in Wayanad 13 4. Shifts in Cropping Pattern 17 5. Cost of Production of Coffee 23 6. Coffee Marketing 30 7. Effects of fall in Price of Coffee 34 8. Conclusions and Suggestions 37 References 3 Small coffee Growers of Sulthan Bathery, Wayanad C.V Joy 1. Introduction Coffee is one of the important plantation crops of India, which is cultivated mainly in the hill tracts of South India especially in Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. The other important States of India in which coffee is grown on a limited scale are Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, West Bengal, Assam, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Madhya Pradesh. The two principal varieties of coffee produced in the world are Arabica (Coffee Arabica) and Robusta (Coffee Canephora). Arabica coffee is the variety which has more beverage value and hence fetches a higher price in the international market. -

Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (Ssa)

SARVA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN (SSA) KERALA District Elementary Education Plan (DEEP) 2003-2004 WAYANAD INSIDE Chapter I - Introduction 1. Historical Background 2.- Social - Economic, Cultural and Linguistic characteristics 3. Geographical conditions 4. Demographic factors ♦ 4(a). Literacy scenario 5. Special features 6. Situational Analysis leading to the launching of SSA 7. Objectives of SSA Chapter n - District Profile 1. Information of Demography 2. Information on Area 3. Information on Literacy Educational Profile 1. Educational Administration in the District , 2. Educational facilities at various levels 3. State and centrally sponsored schemes implementated in the District 4. Details of Externally Funded schemes 5. DIET 6. Block wise number of schools 7. Block wise number of Anganwadies 8. Block wise Access position on Primary Upper Primary Education 9. No. of Tribal Habitations in every Block and Number of School less Habitations . ‘ 2 10. No of Out of children and Reason for Out of school children 11. Block wise details of Alternate schools / EGS Centres 12. Block wise Details of Special schools 13. Details of Teacher Training Institutions 14. Distribution system of Text books 15. Block wise number of teachers at Primary and Upper Primary 16. Block wise - Enrolment Block wise category wise Enrolment Gross and Net Enrolment Ratio Data regarding children with special needs 17. Dropouts 2002 - 2003 18. Block wise position of Buildings and infrastructure of Primary and Upper Primary Schools 19. Block wise school facilities at Primary and Upper primary levels of schools 20. Problems and issues of Elementary Education in the District Chapter III The Planning Process 1. Environment Creation Activities 2. -

Details of Government Colleges

DETAILS OF GOVERNMENT COLLEGES No.of Non-Teaching Name of Sanctio No.of Teaching Staffs Staffs Legislative ned Actual Assembly in Name of intake intake Sl which the college Year of Affiliated Name of Course in each in each Sanctioned Actual Sanctioned Actual No Name & Address of College is situated Starting University Offered course course Strength Strength Strength Strength Thiruvananthapuram BA Economics 60 68 BSc Physics 24 30 BSc Botany & Biotechnology 24 29 B.Com Finnace 50 70 Govt.Arts College,Thycaud, Trivandrum, 1 Trivandrum 1948 Kerala 51 50 30 27 Pin:695014 MA English 15 17 MA Economics 15 16 MSc Analytical Chemistry 10 10 MSc Statistics 12 16 M.Com 10 17 BA Economics 60 68 BA English 25 30 BA English Honours 30 33 BA Hindi 33 38 BA History 70 79 BA Malayalam 32 38 BA Music 14 14 BA Philosophy 70 76 BSc Chemistry 40 42 BSc Biochemistry 29 30 BSc Home Science 29 29 BSc Botany 35 38 BSc Maths 45 54 BSc Physics 29 32 BSc Psychology 26 26 BSc Statistics 32 36 BSc Zoology 35 37 B.Com 39 47 Govt.College for Women ,Vazhuthacaud, 2 Trivandrum 1864 Kerala MA Economics 15 19 154 152 64 70 Thycaud.P.O, Trivandrum,Pin:695014 MA Business Economics 12 18 MA English 15 24 MA History 15 24 MA Hindi 15 20 MA Malayalam 15 24 MA Philosophy 20 25 MA Music 10 8 MSc Maths 15 21 MSc Physics 6 18 MSc Botany 8 13 MSc Zoology 8 13 MSc Chemistry 10 12 MSc Psychology 10 12 MSc Home Science (Food & Nutrition) 8 7 MSc Home Science (Extension & Education) 8 8 M.Com 12 20 BA English 40 53 BA Malayalam 40 46 BA Hindi 40 43 BA History 55 65 BA Economics 53 68