Judicial Tenure and the Politics of Impeachment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between Rhetoric and Reality: the Progress of Reforms Under the Benigno S. Aquino Administration

Acknowledgement I would like to extend my deepest gratitude, first, to the Institute of Developing Economies-JETRO, for having given me six months from September, 2011 to review, reflect and record my findings on the concern of the study. IDE-JETRO has been a most ideal site for this endeavor and I express my thanks for Executive Vice President Toyojiro Maruya and the Director of the International Exchange and Training Department, Mr. Hiroshi Sato. At IDE, I had many opportunities to exchange views as well as pleasantries with my counterpart, Takeshi Kawanaka. I thank Dr. Kawanaka for the constant support throughout the duration of my fellowship. My stay in IDE has also been facilitated by the continuous assistance of the “dynamic duo” of Takao Tsuneishi and Kenji Murasaki. The level of responsiveness of these two, from the days when we were corresponding before my arrival in Japan to the last days of my stay in IDE, is beyond compare. I have also had the opportunity to build friendships with IDE Researchers, from Nobuhiro Aizawa who I met in another part of the world two in 2009, to Izumi Chibana, one of three people that I could talk to in Filipino, the other two being Takeshi and IDE Researcher, Velle Atienza. Maraming salamat sa inyo! I have also enjoyed the company of a number of other IDE researchers within or beyond the confines of the Institute—Khoo Boo Teik, Kaoru Murakami, Hiroshi Kuwamori, and Sanae Suzuki. I have been privilege to meet researchers from other disciplines or area studies, Masashi Nakamura, Kozo Kunimune, Tatsufumi Yamagata, Yasushi Hazama, Housan Darwisha, Shozo Sakata, Tomohiro Machikita, Kenmei Tsubota, Ryoichi Hisasue, Hitoshi Suzuki, Shinichi Shigetomi, and Tsuruyo Funatsu. -

Crime and Poverty: Criminalization and Empowerment of the Poor in the Philippines

INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS INTERNSHIP PROGRAM | WORKING PAPER SERIES VOL 7 | NO. 1 | FALL 2019 Crime and Poverty: Criminalization and Empowerment of the Poor in the Philippines Alicia Blimkie ABOUT CHRLP Established in September 2005, the Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) was formed to provide students, professors and the larger community with a locus of intellectual and physical resources for engaging critically with the ways in which law affects some of the most compelling social problems of our modern era, most notably human rights issues. Since then, the Centre has distinguished itself by its innovative legal and interdisciplinary approach, and its diverse and vibrant community of scholars, students and practitioners working at the intersection of human rights and legal pluralism. CHRLP is a focal point for innovative legal and interdisciplinary research, dialogue and outreach on issues of human rights and legal pluralism. The Centre’s mission is to provide students, professors and the wider community with a locus of intellectual and physical resources for engaging critically with how law impacts upon some of the compelling social problems of our modern era. A key objective of the Centre is to deepen transdisciplinary — 2 collaboration on the complex social, ethical, political and philosophical dimensions of human rights. The current Centre initiative builds upon the human rights legacy and enormous scholarly engagement found in the Universal Declartion of Human Rights. ABOUT THE SERIES The Centre for Human Rights and Legal Pluralism (CHRLP) Working Paper Series enables the dissemination of papers by students who have participated in the Centre’s International Human Rights Internship Program (IHRIP). -

February 19, 2011 February 4, 2012

FeBruAry 4, 2012 hAWAii FiliPino chronicle 1 ♦♦ FFEEBBRRUUAARRYY 149, ,2 2001121 ♦ ♦ HAWAII-FILIPINO NEWS FEATURE LEGAL NOTES Menor Bold dreAM , ProPosed WAiVer Announces uncoMMon VAlor : T he rule exPecTed To council Bid FlorenTino dAs sTory BeneFiT ThousAnds HAWAII FILIPINO CHRONICLE PRESORTED STANDARD 94-356 WAIPAHU DEPOT RD., 2ND FLR. U.S. POSTAGE WAIPAHU, HI 96797 PAID HONOLULU, HI PERMIT NO. 9661 2 hAWAii FiliPino chronicle FeBruAry 4, 2012 EDITORIAL FROM THE PUBLISHER Publisher & Executive Editor he Philippines wasted little time Charlie Y. Sonido, M.D. Preserve Judicial in starting 2012 off with a bang. In case you missed it, trial began Publisher & Managing Editor Independence and on January 16th for Chief Justice Chona A. Montesines-Sonido Renato Corona, the country’s top Associate Editors T lawyer, who is facing impeach - Integrity Dennis Galolo ment on charges of corruption be - Edwin Quinabo he on-going impeachment trial of Supreme Court fore a court composed of Philippine senators. It Chief Justice Renato Corona is not only unprece - is the first such impeachment of a chief justice in Philippine his - Creative Designer Junggoi Peralta dented but also the most difficult in the annals of tory. Supporters of President Benigno “Noynoy” S. Aquino III Philippine political history. It involves legal and con - say it’s about time that the nation’s corrupt officials are held ac - Design Consultant Randall Shiroma stitutional issues, along with political and partisan di - countable for their actions. Others are questioning the constitu - T mensions that make the case much more problematic tionality of the entire process, since it is the Supreme Court’s Photography to resolve. -

Motion for Reconsideration

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES SUPREME COURT MANILA EN BANC REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, REPRESENTED BY SOLICITOR GENERAL JOSE C. CALIDA, Petitioner, – versus – CHIEF JUSTICE MARIA LOURDES P.A. G.R. No. SERENO, 237428 For: Quo Warranto Respondent. Senators LEILA M. DE LIMA and ANTONIO “SONNY” F. TRILLANES IV, Movant-Intervenors. x-------------------------------------------------------------------x MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION Movant-intervenors, Senators LEILA M. DE LIMA and ANTONIO “SONNY” F. TRILLANES IV, through undersigned counsel, respectfully state that: 1. On 29 May 2018, Movant-intervenors, in such capacity, requested and obtained a copy of the Decision of the Supreme Court dated 11 May 2018, by which eight members of the Court voted to grant the Petition for Quo Warranto, resulting in the ouster of Chief Justice Maria Lourdes P.A. Sereno. 2. The Supreme Court’s majority decision, penned by Justice Tijam, ruled that: 2.1. There are no grounds to grant the motion for inhibition filed by respondent Chief Justice Sereno; 2.2. Impeachment is not an exclusive means for the removal of an impeachable public official; MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION Republic of the Philippines v. Sereno G.R. No. 237428 Page 2 of 25 2.3. The instant Petition for Quo Warranto could proceed independently and simultaneously with an impeachment; 2.4. The Supreme Court’s taking cognizance of the Petition for Quo Warranto is not violative of the doctrine of separation of powers; 2.5. The Petition is not dismissable on the Ground of Prescription, as “[p]rescription does not lie against the State”; and 2.6. The Petitioner sufficiently proved that Respondent violated the SALN Law, and such failure amounts to proof of lack of integrity of the Respondent to be considered, much less nominated appointed, as Chief Justice by the Judicial and Bar Council and the President of Republic, respectively. -

REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES Supreme Court of the Philippines En Banc - M a N I L A

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Supreme Court of the Philippines En Banc - M A N I L A ARTURO M. DE CASTRO, JAIME N. SORIANO, PHILIPPINE CONSTITUTIONAL ASSOCIATION (Philconsa), per Manuel Lazaro, & JOHN G. PERALTA, Petitioners, - versus - G.R. Nos. 191002, 191032 & 191057 & 191149 For: Mandamus, Prohibition, etc. JUDICIAL AND BAR COUNCIL and EXECUTIVE SECRETARY EDUARDO ERMITA (LEANDRO MENDOZA), representing the President of the Philippines, GLORIA MACAPAGAL-ARROYO, Respondents. X---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------X In re: Applicability of Article VII, Section 15 of the Constitution to the appointments to the Judiciary, ESTELITO P. MENDOZA, Petitioner, - versus - A.M. No. 10-2-5-SC X--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------X JUDGE FLORENTINO V. FLORO, JR., (123 Dahlia, Alido, Bulihan, Malolos City, 3000 Bulacan) Petitioner-in-Intervention, - versus - G. R. No. ______________________ For: Intervention, etc. X-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------X In re: (Noted, Not Denied by the JBC) Nomination dated February 4, 2010, by Judge Florentino V. Floro, Jr. of Atty. Henry R. Villarica and Atty. Gregorio M. Batiller, Jr. , for the position of Chief Justice subject to their ratification of the nomination or later consent thereof; with Verified Petition-Letter to CONSIDER the case at bar/pleading/Letter, an administrative matter and cause -

Power of Partnership: 50+ Years of USAID in the Philippines

POWER OF PARTNERSHIP 50+ YEARS OF USAID IN THE PHILIPPINES POWER OF PARTNERSHIP 50+ YEARS OF USAID IN THE PHILIPPINES Copyright 2017 by United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Philippines. U.S. Embassy, 1201 Roxas Boulevard Ermita, Manila, Philippines Postal Code - M 1000 Phone +63 (2) 301-6000 Fax +63 (2) 301-6213 ABOUT THE PHOTO SPREAD Students of Sto. Niño Central Honored here are the individuals, families, Elementary School in South Cotabato pose with their school communities and partners — both Filipino principal. USAID helped strengthen the capacity of teachers in more and American — that have worked tirelessly than 660 primary schools in to build a brighter future for the Philippines. Mindanao. USAID partnered with the Philippine Department of Education, corporations, foundations and non-governmental organizations to build the foundational reading and numeracy skills of young students. RIGHT PHOTO The Bohol local government and community members in Buenavista have been successfully co-managing the Cambuhat River Village Tour and Oyster Farm. USAID helped train local leaders about the value of partnerships in sustainable development. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS USAID would like to thank the following people, organizations and agencies for sharing their time, expertise and insights to make this book possible. We are eternally grateful for their valuable contribution. Partners, beneficiaries, employees and friends of USAID who generously shared their experiences and perspectives, including:* USAID Projects – Accelerating Growth -

Corona Impeachment Trial Momblogger, Guest Contributors, Press Releases, Blogwatch.TV

Corona Impeachment Trial momblogger, Guest Contributors, Press Releases, BlogWatch.TV Creative Commons - BY -- 2012 Dedication Be in the know. Read the first two weeks of the Corona Impeachment trial Acknowledgements Guest contributors, bloggers, social media users and news media organizations Table of Contents Blog Watch Posts 1 #CJTrialWatch: List of at least 93 witnesses and documentary evidence to be presented by the Prosecution 1 #CJtrialWatch DAY 7: Memorable Exchanges, and One-Liners, AHA AHA! 10 How is the press faring in its Corona impeachment trial coverage? via @cmfr 12 @senmiriam Senator Santiago lays down 3 Crucial Points for the Impeachment Trial 13 How is the press faring in its Corona impeachment trial coverage? via @cmfr 14 Impeachment and Reproductive Health Advocacy: Parellelisms and Contrasts 14 Impeachment Chronicles, 16-19 January 2012 (Day 1-4) via Akbayan 18 Dismantling Coronarroyo, A Conspiracy of Millions 22 Simplifying the Senate Rules on Impeachment Trials 26 Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN) 36 #CJTrialWatch: Your role as Filipino Citizens 38 Video & transcript: Speech of Chief Justice Renato Corona at the Supreme Court before trial #CJtrialWatch 41 A Primer on the New Rules of Procedure Governing Impeachment Trials in the Senate of the Philippines 43 Making Sacred Cows Accountable: Impeachment as the Most Formidable Weapon in the Arsenal of Democracy 50 List of Congressmen Who Signed/Did Not Sign the Corona Impeachment Complaint 53 Twitter reactions: House of Representatives sign to impeach Corona 62 Full Text of Impeachment Complaint Against Supreme Court Chief Justice Renato Corona 66 Archives and Commentaries 70 Corona Impeachment Trial 70 Download Reading materials : Corona Impeachment trial 74 Blog Watch Posts #CJTrialWatch: List of at least 93 witnesses and documentary evidence to be presented by the Prosecution Blog Watch Posts #CJTrialWatch: List of at least 93 witnesses and documentary evidence to be presented by the Prosecution Lead prosecutor Rep. -

Southeast Asia from the Corner of 18Th & K Streets

Chair for Southeast Asia Studies Southeast Asia from the Corner of 18th & K Streets Volume III | Issue 23| December 6, 2012 Aligning U.S. Structures, Process, and Strategy: A U.S.-ASEAN Strategic and Inside This Issue the week that was Economic Partnership ernest z. bower • Myanmar government takes action against copper mine protesters Ernest Z. Bower is senior adviser and holds the Chair for Southeast Asia Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies • Indonesian vice president Boediono faces in Washington, D.C. unlikely impeachment • Thai prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra December 6, 2012 survives no-confidence vote looking ahead The transition between President Barack Obama’s first and second terms is the right time to develop a U.S.-ASEAN Strategic and Economic • Discussion on climate change and development Partnership (SEP). The move would serve to elevate and institutionalize in Thailand existing U.S.-ASEAN engagements. It would also compel U.S. departments • Hugh White on Australia in the “Asian Century” and agencies that have been compartmentalized and uncoordinated to raise their levels of engagement, share information, and align government • Banyan Tree Leadership Forum with Philippine mandates with strategic objectives. Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno President Obama made dual commitments with his ASEAN counterparts at the fourth U.S.-ASEAN Leaders’ Meeting in Phnom Penh in November— to convert that forum into a summit, thereby indicating that the U.S. president will participate annually, and to raise the U.S.-ASEAN relationship to the “strategic level.” Creating the SEP could create a foundation for the president’s Asia Pacific policy in his second term. -

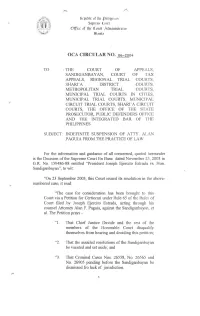

Oca Circular No. 06-2004

Hepublic of tlJe -t1t}i1ippillC9 ~uprcrnt l.ourt <Officl of tlJc (Ollrt ,.AbministrMor mdnila OCA CIRCULAR NO. 06-2004 TO : THE COURT OF APPEALS, SANDIGANBAYAN, COURT OF TAX APPEALS, REGIONAL TRIAL COURTS, SHARl' A DISTRICT COURTS, METROPOLITAN TRIAL COURTS, MUNICIPAL TRIAL COURTS IN CITIES, MUNICIPAL TRIAL COURTS, MUNICIPAL CIRCUIT TRIAL COURTS, SHARI' A CIRCUIT COURTS, 'mE OFFICE OF THE STATE PROSECUTOR, PUBLIC DEFENDERS OFFICE AND THE INTEGRATED BAR OF THE PHILIPPINES SUBJECT: INDEFINITE SUSPENSION OF ATTY. ALAN PAGUIA FROM THE PRACTICE OF LAW For the information and guidance of all concerned, quoted hereunder is the Decision of the Supreme Court En Banc dated November 25,2003 in G.R No. 159486-88 entitled '"President Joseph Ejercito Estrada vs. Hon. Sandiganbayan", to wit: "On 23 September 2003, this Court issued its resolution in the above- numbered case, it read: "The case for consideration has been brought to this Court via a Petition for Certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court filed by Joseph Ejercito Estrada, acting through his counsel Attorney Alan F. Paguia, against the Sandiganbay®, et al. The Petition prays - . "1. That Chief Justice Davide and the rest of the members of the Honorable Court disqualify themselves from hearing and deciding this petition~ "2. That the assailed resolutions of the Sandiganbayan be vacated and set aside~and "3. That Criminal Cases Nos. 26558, No. 26565 and No. 26905 pending before the Sandiganbayan be dismissed fro lack of jurisdiction. 1 <CAttorneyAlan F. Paguia, speaking for petitioner, asserts that the inhibition of the members of the Supreme Court from hearing the petition is called for under Rule 5.10 of the Code of Judicial Conduct prohibiting justices or judges from participating in any partisan political activity which proscription, according to him, the ju'stices have violated by attending the 'EDSA 2 RALLY' and by authorizing the assumption of Vice-president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo to the Presidency in violation of the 1987 Constitution. -

~Upreme <!L:Ourt

l\epublic of tbe tlbilippines ~upreme <!l:ourt ;fflanila EN BANC REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES, G.R. No. 237428 represented by SOLICITOR GENERAL JOSE C. CALIDA, Petitioner, Present: SERENO, C.J.,* CARPIO, VELASCO, JR., LEONARDO-DE CASTRO, PERALTA, BERSAMIN, DEL CASTILLO, PERLAS-BERNABE, - versus - LEONEN, JARDELEZA, CAGUIOA, MARTIRES, TIJAM, REYES, JR., and GESMUNDO, JJ. Promulgated: MARIA LOURDES P.A. SERENO Respondent. May 11, 20~ x---------------------------------------------------------~--------------------x DECISION TIJAM, J.: Whoever walks in integrity and with moral character walks securely, but he who takes a crooked way will be discovered and punished. -The Holy Bible, Proverbs 10:9 (AMP) 'No Part. Decision 2 G.R. No. 237428 Integrity has, at all times, been stressed to be one of the required qualifications of a judge. It is not a new concept in the vocation of administering and dispensing justice. In the early l 600's, Francis Bacon, a philosopher, statesman, and jurist, in his "Essay L VI: Of Judicature" said - "'[a]bove all things, integrity is the Judge's portion and proper virtue." Neither is integrity a complex concept necessitating esoteric philosophical disquisitions to be understood. Simply, it is a qualification of being honest, truthful, and having steadfast adherence to moral and ethical principles. 1 Integrity connotes being consistent - doing the right thing in accordance with the law and ethical standards everytime. Hence, every judicial officer in any society is required to comply, not only with the laws and legislations, but with codes and canons of conduct and ethical standards as well, without derogation. As Thomas Jefferson remarked, "it is of great importance to set a resolution, never not to be shaken, never to tell an untruth. -

PLM Law Gazette February 2012 E-Newsletter.Pdf

Film & Book Impeachment Reviews 7 10 Volume 1 Number 2 The Official Student Publication of the PLM College of Law February 2012 28 from PLM Law take 1st MCQ Bar Former Defense Secretary Gilberto “Gibo” Teodoro BY ROLLIE C. ANG answers queries from students coursed through PLM College of Law Dean Ernesto Maceda, Jr. Twenty-eight out of the 6,200 bar examinees who Photo by Mary Eileen F. Chinte took the first bar examinations that included Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ) at the University of Santo Tomas last November were graduates of the PLM College of Law. Of the 28 PLM examinees, 19 are first takers. For the first time in the history of the Philippine bar examinations, the qualifying exam for aspiring lawyers is composed of Multiple Choice Questions, and Trial Memorandum and Legal Opinion. Supreme Court Associate Justice Roberto Abad, chairman of the 2011 Committee on Bar Examinations, 28 from PLM/to page 2 MAKING A STATEMENT. Banners expressing support to Supreme Court Chief Justice Renato Corona adorn the facade of the SC Main Building in Manila. Corona is facing an impeachment case after allies of President Benigno Gibo gives perspectives “Noynoy” Aquino III in the House of Representatives transmitted the complaint to the Senate, which is now acting as the impeachment court. Photo by Rommel C. Lontayao on law, public service BY SARITA G. ALVARADO many people in government “There is doing nothing and claimed underinvestment in public Former Defense otherwise. service in the government Secretary Gilberto “Gibo” “Based on my here, by government on Teodoro, Jr., lectured and experience in the continuing education of its answered queries regarding Department of National officers and contingents,” the country’s major Defense, there are people “Government, in my concerns on economic doing the jobs of four or five,” experience, is swamped productivity and peace he said. -

The Role of Philippine Courts in Establishing the Environmental Rule Of

Copyright © 2012 Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, DC. Reprinted with permission from ELR®, http://www.eli.org, 1-800-433-5120. ifty years ago, there was little “environmental rule The Role of of law” in the United States . It was a time when a community could be built on top of a toxic waste Fdump (Love Canal) and a river, oozing with oil slicks, Philippine could catch on fire (the Cuyahoga River) . The legal land- scape began to change in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the enactment of watershed laws like the National Courts in Environmental Protection Act (NEPA),1 the Clean Air Act (CAA),2 and the Clean Water Act (CWA) 3. But these Establishing the aspirational laws were not enough to clean up the environ- ment . Federal courts were instrumental in making NEPA and other laws a reality . Newly established environmental Environmental agencies4 likewise played an important role in carrying out the laws . In developing countries that have enacted environ- Rule of Law mental laws similar to those in the United States, it is apparent that legislative action alone is not enough . Environmentalists around the world have hailed judicial efforts, such as those of the Indian Supreme Court, to implement environmental laws in the face of executive apathy or inability . At the same time, this judicial activ- Author’s Note: Many thanks to my Filipino colleagues who by Elizabeth Barrett Ristroph generouslysharedtheirtimeandknowledgeofPhilippinelawwith Elizabeth Barrett Ristroph served as a legal specialist in the me,includingProf.Gloria(Golly)EstenzoRamosoftheUniversity Manila office of the American Bar Association Rule of Law of CebuCollegeofLawandthePhilippineEarthJusticeCenter, Initiative (ABA ROLI) in 2011 and 2012 .