Film a Re-Reading of the Jungle Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jungle-Book-Playbill-Virtual.Pdf

Virginia’s Leading Family Theatre Company Hugh R. Copeland—Artistic Director PRODUCTION STAFF Director…………..……..….………..……………...………………… HUGH R. COPELAND Production Stage Manager……….……………………………….………….LAURA LAVAN Sponsored in part by Costume Designer……………………………………………….………...…..ANNE HILTON Costumers Volunteers……..….ROBIN POWELL, STACY CARTWRIGHT AND KATY DOTY, SEPHANIE TREVINO Set Crew…………………………….SCOTT CHASEY, BECKY CHASEY, ANDY THORNHILL KATY DOTY, DEANNA HAMMOND, JOHN LAPETINA, ALAN TAYLOR, JIMMY MCKENZIE AND KAYVON HOSSEINIPOOR Photographer………………………………………………………………….....JERRY DUCK Stage Managers………………………………… ANDY THORNHILL, STEPHANIE TREVINO Backstage Crew……….. SHANNON THORNHILL, LAURIE GLICK, MARIE VACCARELLA, KATY DOTY, ANGELA TAYLOR, THERESA BREMBY, JENNIFER WHITMORE, BETTINA SELBY, JESSICA MCKENZIE, MEGAN HOOSEINIPOOR Music and Lyrics by House Managers………………………………...THERESA HYLER, STACEY CARTWRIGHT Richard M. Sherman, Robert B. Sherman Ushers………………… ANGELA TAYLOR, SHAWTINA CROSS, MEGAN HOSSEINIPOOR THERESA BREMBY, KATY DOTY, DAWN KERMAN, VALERIE WANG, KELLY YOUNG And Terry Gilkyson JESSICA MCKENZIE Book adapted and Additional Lyrics by Marcy Heisler HURRAH STAFF Founder and Artistic Director……………………………………......HUGH. R. COPELAND Music Adapted and Arranged by Managing Director………………………………………....………..…….….KELSEY BACKE Bryan Louiselle Director of Education/ Box Office Manager…………………...…..……....LISA WALLACE Director of Development……………………………………………..…EILEEN CARPENTER Based on the Screenplay by Production Manager…………………………...………………………..…….LAURA -

1895 the SECOND JUNGLE BOOK Rudyard Kipling

1 1895 THE SECOND JUNGLE BOOK Rudyard Kipling Kipling, Rudyard (1865-1936) - An English novelist, short-story writer, and poet who spent most of his youth in India, and is best known for his children’s classics. In 1907, Kipling was the first English writer ever to be awarded the Nobel Prize in literature. The Second Jungle Book (1895) - A sequel to “The Jungle Book.” This volume presents more animal stories for children, many of which again include the jungle boy, Mowgli, as the central character. 2 Table Of Contents HOW FEAR CAME . 3 THE LAW OF THE JUNGLE . 15 THE MIRACLE OF PURUN BHAGAT . 17 A SONG OF KABIR . 28 LETTING IN THE JUNGLE . 29 MOWGLI’S SONG AGAINST PEOPLE . 49 THE UNDERTAKERS . .50 A RIPPLE SONG . 66 THE KING’S ANKUS . 67 THE SONG OF THE LITTLE HUNTER . 80 QUIQUERN . 81 ANGUTIVUN TINA . 99 RED DOG . 100 CHIL’S SONG . 118 THE OUTSONG . 134 3 HOW FEAR CAME The stream is shrunk- the pool is dry, And we be comrades, thou and I; With fevered jowl and dusty flank Each jostling each along the bank; And by one drouthy fear made still Forgoing thought of quest or kill. Now ‘neath his dam the fawn may see, The lean Pack-wolf as cowed as he, And the tall buck, unflinching, note The fangs that tore his father’s throat. The pools are shrunk- the streams are dry, And we be playmates, thou and I, Till yonder cloud- Good Hunting!- loose The rain that breaks our Water Truce. The Law of the Jungle- which is by far the oldest law in the world- has arranged for almost every kind of accident that may befall the Jungle People, till now its code is as perfect as time and custom can make it. -

Empathy in Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Books, Mirrored in Illustrations By

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, January 2018, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1-31 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2018.01.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Empathy in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Books, Mirrored in Illustrations by John Lockwood Kipling and Aldren Watson Norman Arthur Fischer Kent State University (Retired), Kent, Ohio, USA Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Books depict empathy in the animal and animal-human world, and the illustrations of Rudyard’s father, John Lockwood Kipling, and the American artist and prolific illustrator, Aldren Watson, help depict that empathy. Lockwood Kipling was both influence on and interpreter of the Jungle Books, as shown above all in the development from his Beast and Man in India of 1891 through his illustrations for the 1894 Jungle Book, and 1895 Second Jungle Book, to his illustrations that appear in the rearranged stories of The Jungle Book, and Second Jungle Book in the 1897 Scribners Outward Bound (O/B) editions. A variation on Lockwood’s O/B mode of Jungle Books illustrations is found in Watson’s illustrations for the 1948 Doubleday edition, Jungle Books, which is the title I will use throughout.1 Part One details the influence of two animal empathy writers, Lockwood Kipling and Ernest Thompson Seton, on the Jungle Books. Part Two uses recent philosophical studies of empathy in the animal and human relationship. Part Three applies a German philosophy of art history to the new look of the O/B and Doubleday Jungle Books. Part Four interprets selected Jungle Books stories in the light of Parts one, two and three. -

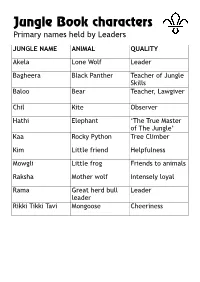

Jungle Book Characters Primary Names Held by Leaders

Jungle Book characters Primary names held by Leaders JUNGLE NAME ANIMAL QUALITY Akela Lone Wolf Leader Bagheera Black Panther Teacher of Jungle Skills Baloo Bear Teacher, Lawgiver Chil Kite Observer Hathi Elephant ‘The True Master of The Jungle’ Kaa Rocky Python Tree Climber Kim Little friend Helpfulness Mowgli Little frog Friends to animals Raksha Mother wolf Intensely loyal Rama Great herd bull Leader leader Rikki Tikki Tavi Mongoose Cheeriness Jungle Book characters Secondary names held by Leaders JUNGLE NAME ANIMAL QUALITY Grey Brother Brother Wolf Loyal friend Ikki Porcupine Truthful Jacala Crocodile Acting Mang Bat Obedience Mao / Mor Peacock Smart appearance Mysa Wild Buffalo Good hearing Phao Wolf Leader (to be) Wontolla Solitary Wolf Lies out from any Pack / hopping Other names held by Leaders JUNGLE NAME ANIMAL QUALITY Father Wolf Wolf Father Kala Nag The Wise Old (Name meaning: Elephant Black Snake) Tha First of Elephants Creator & Judge Jungle Book characters Jungle villains JUNGLE NAME ANIMAL QUALITY Bander-log Monkey People People without a Law Buldeo Village Hunter Hunter & teller of stories (about himself) Dewanee Water Madness Feared by all Jungle Creatures Dholes Red Dogs Killers Gidur-log Jackel People - Gonds Hunters Little wild people of the jungle Grampus Killerwhale Killer Karait Dusty Brown Death Snakeling Ko Crow Chatter Mugger Ghaut Large Crocodile - Nag Cobra Kills for pleasure Nagaina Nag’s Wicked Wife Kills for pleasure Sea Vitch Walrus No manners Samthur Cattle - Shere Khan Tiger Bullying & Killer Tabaqui -

A Study Companion

The Jefferson Performing Arts Society Presents A Study Companion 1118 Clearview Pkwy, Metairie, LA 70001 Ph 504.885.2000 Fx 504.885.3437 [email protected] www.jpas.org 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TEACHERS’ NOTES……………………………………………………….3 LOUISIANA CONTENT STANDARDS………………………………….4 Jungle Book, THE BOOK……………………………………………….…….5 Rudyard Kipling, THE AUTHOR………………………………………….27 KIPLING’S INFLUDENCE ON CULTURE…………………………………....36 The Jungle Book, THE FILMS………………………………………………….…42 The Jungle Book, THE PLAY……………………………………………………...52 LESSONS………………………………………………………………………….55 RESOURCE LIST…………………………………………………………………….106 2 TEACHERS’ NOTES JPAS Theatre Kids! take the stage once more in another classic Disney tale brought to life through song and dance on stage! Performed by an all-kid cast, the jungle is jumpin' with jazz is this exciting Disney classic! Join Mowgli, Baloo, King Louie and the gang as they swing their way through madcap adventures and thwart the ferocious tiger, Shere Khan. With colorful characters and that toe-tapping jungle rhythm, The Jungle Book KIDS is a crowd-pleaser for audiences of all ages! Music by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman and Terry Gilkyson Lyrics by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman and Terry Gilkyson Additional lyrics by Marcy Heisler Book adapted by Marcy Heisler Music adapted by Bryan Louiselle Music arranged by Bryan Louiselle This Study Companion provides background information on Rudyard Kipling’s book, published in 1894, biographical information on Kipling, background information on the Disney films and play and lesson plans that pull directly from the book, films and play. One focus of the lesson plans is to highlight how an author’s individual voice can shape the telling and re-telling of a tale. -

Cubs Membership Award

Cubs Membership Award What is Cubs and Its Theme ‘The Jungle Book’, Group Name & Leader© By Samantha Eagle © All Rights Reserved 2013 © All Rights Reserved 2013 Copyright Notices © Copyright Samantha Eagle All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical or electronic, including photocopying and recording, or by any information and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The purchaser is authorised to use any of the information in this publication for his or her own use ONLY. For example, if you are a leader trainer you are within your rights to show any or all of the material to other leaders within your possession. However it is strictly prohibited to copy and share any of the materials with anyone. Requests for permission or further information should be addressed to Samantha Eagle, PO Box 245, La Manga Club Murcia, 30389, Spain. Published by Samantha Eagle PO Box 245, La Manga Club Murcia, 30389, Spain. Email: [email protected] Legal Notices While all attempts have been made to verify information provided in this publication, neither Author nor the Publisher assumes any responsibility for errors, omissions, or contrary interpretation of the subject matter given in this product. Page | 1 © All Rights Reserved 2014 Cubs Membership Award What is Cubs and Its Theme The Jungle Book, Group Name & Leader© Overview The theme of Cubs is based on the ´Jungle Book´ by Rudyard Kipling. Many of the tales in the Jungle Book relate to what the children do in Cubs. -

Colonel Hathi, Elephant Leader: Scene 4: Dawn Patrol (Commanding, Pompous, Self-Important)

COLONEL HATHI, ELEPHANT LEADER: SCENE 4: DAWN PATROL (COMMANDING, POMPOUS, SELF-IMPORTANT) Hathi: Silence in the ranks! [he walks around the rank] Dress up that line. Inspection... arms! [Elephants stick their trunks out] Hathi (to Elephant #2): Hmmmmmm.... A dusty muzzle. Soldier, remember in battle that trunk can save your life. Take good care of it, my man. Elephant #2: Yes, Sir! Hathi: Very good, carry on. [Hathi looks at Elephant #3 who is chewing on some grass] Ahem. Hmmmmm. Let's have a little more spit and polish on those bayonets Elephant #3: Yes, Sir! [Comes to Hathi Jr. now] And as for you-- [he looks down at him] Oh, there you are. Heh-heh-heh. Let's keep those heels together, shall we, son? Hathi Jr.: Okay Pop... I mean.. Sir! Hathi: That's better. Elephants march and sing: Hup, two, three, four Keep it up, two, three, four Hup, two, three, four Keep it up, two, three, four Hup, two, three, four Hathi: Company... sound off! Elephants sing: Oh, the aim of our patrol Is a question rather droll For to march and drill Over field and hill [they trumpet] Hathi: Is a military goal all: Is a military goal! With a hup, two, three, four Dress it up, two, three, four By the ranks or single file Over every jungle mile Oh we stamp and crush Through the underbrush [Hathi Jr. trumpets] Hathi Jr.: In the military style! Elephants: In the military style SCENE 5: BALOO (JOLLY, FUN, LOVES MUSIC AND DANCING) Baloo (singing): Doo-bee doo-bee doo-bee dee-doo Well, it's a doo-bah-dee-do Yes, it's a doo-bah-dee-do I mean a doo-be doo-bee doo-be Doo-be doo-bee doo [he sees Mowgli] Well now, ha-ha! What have we here? [he sniffs Mowgli] Hmm. -

1 the Jungle Book Scene 1

1 The Jungle Book Scene 1: Mowgli’s Found in the Jungle Basu: Many strange legends are told of these jungles of India. But none as strange as the story of a small boy named Mowgli. It all began when the silence of the jungle was broken by an unfamiliar sound. (O.S. Baby is crying) It was a sound like one never heard before in this part of the jungle. Bagheera: (enters on stage) It’s a man-cub! Basu: Had Bagheera known how deeply he would be involved with Mowgli, he might have obeyed his first impulse to walk away. But Bagheera knew this man-cub would need nourishment, and soon. It would take many days to travel to the nearest man-village, and without a mother's care, well, he would soon perish. Then it occurred to him. (Bagheera grabs the basket by his mouth and starts walking to the corner to the wolves’ family den. Bagheera places basket by cave and nudges basket, creating a cry from Mowgli. Bagheera hides on the side of the stage watching the interaction of Mother Raksha and 4 wolf cubs coming to see what the noise was) Basu: Bagheera knew a family of wolves that had been blessed with a litter of cubs, and he believed there'd be no problem with the mother, Raksha, accepting this man-cub into the family thanks to maternal instinct. But he wasn’t so sure about Rama, the father. [Rama comes from side stage, looks at the man-cub and smiling face of Raksha, looks at cute Mowgli again and smiles too.] Basu: Ten times the rains have come and gone. -

Character Breakdown Mowgli Mowgli Is a Boy Who Gets Along with Everyone and Who Is Very Likable

Character Breakdown Mowgli Mowgli is a boy who gets along with everyone and who is very likable. He has a joyful and curious nature, and a twinkle in his eye. The child you cast should have a spark that can captivate the audience and should be a bit feisty. Choose a boy with a natural talent for acting and singing. Gender: Male Bagheera The role of Bagheera, the panther, is not gender-specific. You might consider casting a female to play this role to help balance the male-to-female ratio of the leading characters. Consider casting a child who might easily portray the physical attributes of a feline. Your Bagheera should be physically agile and uninhibited with good command of his or her body. The actor should also possess a natural talent for acting, singing and leading a story. Bagheera should act like an older brother or sister to Mowgli. Gender: Both Baloo Baloo, the bear, should be cast by someone who is exuberant with a great natural talent for singing and acting. Baloo provides much of the comedic relief in the story, so the actor must possess a natural sense of comedy. Consider casting a child who might easily have the physical traits of a big bear and who is not afraid to be wild and crazy and physically uninhibited. The actor should not be self-conscious and should enjoy the spotlight. Baloo's part in "I Wan'na Be Like You" demands a singer with a strong sense of rhythm. Gender: Male Kaa Kaa, the snake, supplies threat and danger to Mowgli's journey out of the jungle. -

1 Scene 12: the Fight

============================================================================= THE JUNGLE BOOK Script 15.0 (GF adapted version: 12/12/2013) THE CAST (in order of appearance of the voices) Bagheera The Panther Mowgli The Boy Akela Wolf Leader Rama Wolf Dad Wolf Mom & siblings Baloo Bear Kaa Snake Colonel Hathi Elephant Winifred (elephant mom) Hathi Jr. (baby elephant) Elephants 3-10 King Louie Orangutan Monkeys 2-10 Shere Khan The Tiger Buzzy, Flaps, Ziggy, Dizzy Vultures Village Girl Village Girl Chorus Jungle Choir SCENE 1: INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 2 My Own Home ....................................................................................................................... 2 Leader of the Pack .................................................................................................................. 2 SCENE 2: WOLF COUNCIL ..................................................................................................... 3 SCENE 3: SETTING OUT ......................................................................................................... 4 The Man-Cub Sleeps Tonight ................................................................................................. 4 SCENE 4: DAWN PATROL ...................................................................................................... 6 Colonel Hathi’s March ............................................................................................................ 6 SCENE -

About Scouting

Chapter01 WCLH Eng 09.qxd 4/30/09 9:13 AM Page 1 Chapter 1 - All About Scouting To understand how Cubbing can meet a Cub’s needs, let’s examine what Scouts Canada is trying to accom- plish. We’ll look at Scouting’s Principles and Mission, then see how Cubbing meets the Principles and Mission through the Cub program goals. Finally, we’ll see how to turn these into activities for Cubs through Scouting’s Practices. Scouting’s Principles Scouting is based on three broad principles, which represent its fundamental beliefs. Duty to God This is defined as: “Adherence to spiritual principles, loyalty to the religion that expresses them and acceptance of the duties resulting therefrom.” Duty to Others This is defined as: “Loyalty to one’s country in harmony with the promotion of local, national and international peace, understanding and cooperation,” and “Participation in the development of society, with recognition and respect for the dignity of one’s fellow-being and for the integrity of the natural world.” Duty to Self This is defined as: “Responsibility for the development of oneself.” This is in harmony with the educational purpose of the Scout Movement whose aim is to assist young people in the full development of their potential. Scouting’s core philosophy and values are expressed by the Principles. These form a “code of ethics” for how Scouting expects all members to conduct themselves while participating in activities. Cub Promise, Law and Motto The Cub Promise, Law, and Motto express the Principles in Cub terms. The Cub Promise I promise to do my best To love and serve God; To do my duty to the Queen; To keep the Law of the Wolf Cub pack; And to do a good turn for somebody every day. -

Jungle Book Audition Scripts

Nyra, Chitra Chitra brings the audience to an old, NYRA: Visitors? (NYRA moves towards Chitra and well-known storyteller to hear Mowgli’s story. squints out into audience.) So we do, so we do. And there's no need to tell me why they're here. Visitors NYRA: (Squinting) Who's there? Who speaks? Is that come to this village for only one reason: to hear the you, Chitra? story of the jungle boy. The one the wolves named CHITRA: Yes, Nyra. Mowgli. (Chuckles) What a peculiar name to give a child, for it means Little Frog. Did you ever hear the NYRA: Come closer. Don't make me squint. You know my like? Only I, Nyra, know the true story. You'll have to pay eyes aren't what they once were. Did I hear you something to hear it, though. A good storyteller is worth speaking with someone? a coin or two. I can't be expected to tell this strange CHITRA: Yes. account week in and week out without something to NYRA: Who was it? (RIKKI-TIKKI dances in.) There's that show for my trouble. mongoose again. Must he follow you everywhere you CHITRA: Our visitors gave me a coin of worth. go? (To Rikki-Tikki) Begone! NYRA: A coin of worth, eh? I'll be the judge of that. Let CHITRA: He means no harm. me see it. (She holds out her hand and CHITRA gives NYRA: No harm? Last week he turned over my cooking her a coin. She quickly hides the coin in a pocket.