Louis Johnson by E.E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhythmandblues

RHYTHMANDBLUES Black PDs Examine Reasons TOP 7514LBUMS For Lack Of R&B Airplay Weeks Weeks by Carita Spencer On On 12/24 Chart 12/24 Chart LOS ANGELES - The reasons sur- trend towards mellower is a "cop out," 1 ALL IN ALL 37 NEW HORIZON rounding the issue of the difficutly black stating that songs like Dorothy Moore's EARTH, WIND & FIRE ISAAC HAYES (Polydor PD -1-6120) 44 6 R&B singles are experiencing in receiving "With Pen In Hand," "You Are My Friend," (Columbia JC 34905) 1 5 by Patti LaBelle and the 38 COCOMOTION airplay from Top 40 stations and the subse- Blackbyrds' "Soft 2 LIVE! EL COCO (AVI 6012) 35 12 quent decline in the number of R&B singles And Easy" are all examples of "soft pretty THE COMMODORES on the pop are music" which is conducive to the formats of (Motown M9 -894A2) 2 8 charts varied, depending on CHIC these stations. "There seems a (Atlantic SD 5202) 58 4 who is responding. A number of program to be stigma 3 REACH FOR IT directors and one music director affiliated attached to R&B music," he said. GEORGE DUKE (Epic JE 34883) 3 12 40 HEADS with Los Angeles area black radio stations "Everything that comes out R&B is not a BOB JAMES 4 IN FULL BLOOM (Columbia/Tappan Zee JC 34896) 33 7 were given the opportunity to voice their disco -boogie number. Young white kids ROSE ROYCE (Whitfield/WB WH3074) 4 20 opinions concerning this matter in an effort are dancing and are into R&B music more t1 THE BELLE ALBUM to shed a than ever before. -

Wszystkie 2013

29/12/2013 [ Radio RAM ] === THE CACTUS CHANNEL / Who Is Walt Druce? [HopeStreet (LP)] EX-FRIENDLY f/ Rich Medina / Journey Man (Jonno & Tommo remix) [People Are Looking At You (12")] ANTHONY JOSEPH & THE SPASM BAND / Griot (live) [Heavenly Sweetness (LP)] THE CACTUS CHANNEL / Laika [HopeStreet (LP)] J-BOOGIE'S DUBTRONIC SCIENCE f/ Rich Medina / Same Ol Thang [Om (LP)] DJ MITSU THE BEATS f/ Rich Medina / Do Right [Planetgroove (LP)] DA LATA f/ Rich Medina / Monkeys And Anvils [Agogo (LP)] NATH & MARTIN BROTHERS / Livingstone [Voodoo Funk/Honest Jon's (LP)] NATH & MARTIN BROTHERS / Livingstone (highlife) [Voodoo Funk/Honest Jon's (LP)] CHARLES MINGUS / II B.S. (RZA's Mingus Bounce remix) [Verve (LP)] GANG STARR / I'm The Man [Chrysalis (LP)] DONNY HATHAWAY / Sugar Lee [Atlantic (LP)] THE FUTURE SOUND / Star Struck (Caterpillar Style) [EastWest (LP)] KWEST THA MADD LAD / I Ain't The Herb [No Sleep (LP)] IKE & TINA TURNER / Cussin', Crying And Carryin' On [Unio Square (LP)] KWEST THA MADD LAD / Disk And Dat [American/BMG (LP)] DAS EFX / Here We Go [Eastwest (LP)] DENIECE WILLIAMS / How'd I Know That Love Would Slip Away [Sony BMG (LP)] BIZ MARKIE / Games [Groove Attack (12")] THE MIKE SAMMES SINGERS & THE TED TAYLOR ORGANSOUND / He Who Would Valient Be [Trunk (LP)] SOUNDSCI / Remedy [Crate Escape (EP)] YOUNG-HOLT UNLIMITED / Wah Wah Man [Rhino (LP)] SHOWBIZ & A.G. / Hard To Kill [London/Payday (LP)] LORD FINESSE & DJ MIKE SMOOTH / Baby, You Nasty [Wild Pitch (LP)] THE FUTURE SOUND / Jungle-O [EastWest (LP)] IDRIS MUHAMMAD / Crab Apple [Strictly Breaks (LP)] KWEST THA MADD LAD / Blasé Blah (Off That Head) [American/BMG (LP)] RUN-D.M.C. -

Descargar De Audio De La Más Alta Calidad Y Excelente Incluye Simulación De Amplificadores Y De Grabación, De Modo Que Podrías Trabajo a La CPU De Nuestro Ordenador

Fotografía: Stella K. Nº 51 SEPT - OCT ‘19 ACTUAR HECHOS PARA INSPECTOR: MODEL: PICKUPS: NECK: SERIES: COLOR: TUNERS: FRETS: ©2019 Fender Musical Instruments Corporation. FENDER, FENDER en letra cursiva, STRATOCASTER, PRECISION BASS y el clavijero distintivo que se encuentra comúnmente en las Guitarras y Bajos Fender son marcas registradas de FMIC. Yosemite es una marca registrada de FMIC. Todos los derechos reservados. los derechos de FMIC. Todos registrada es una marca de FMIC. Yosemite registradas son marcas y Bajos Fender comúnmente en las Guitarras que se encuentra distintivo y el clavijero PRECISION BASS STRATOCASTER, cursiva, FENDER, FENDER en letra Musical Instruments Corporation. Fender ©2019 PRESENTAMOS LA SERIE AMERICAN PERFORMER SERIES CON NUEVAS PASTILLAS YOSEMITE™, FABRICADAS A MANO EN CORONA, CALIFORNIA. ARTIST: 4 bajos Musicman Stingray 4 Special Fender Telecaster Bass ‘68 12 efectos Audient Sono Ebs Billy Sheehan Signature drive 20 entrevistas Michael League 25 didáctica casi 29 famosos 32 biblioteca B&B MAGAZINE #51 Muchas veces traemos hasta estas páginas a bajistas de primer nivel como instrumentistas, como músicos y a veces con habilidades complementarias relacionadas con los arreglos, la producción etc. El artista que presentamos en este número es Michael League, ganador de 3 Grammys con su banda Snarky Puppy y que en paralelo mantiene actividad al menos con grupos como Bokanté y con David Crosby, legendario miembro de The Byrds y CSN&Y. En una entrevista en profundidad nos habla de cómo es su relación con la música, su enfoque y como forma parte de su vida cotidianamente. En el apartado de reviews contamos entre otros con un Music Man Stingray 4 Special, el interface analógico de Audient Sono y el EBS Billy Sheehan Signature Drive, la tercera versión de esta unidad. -

Soul Top 1000

UUR 1: 14 april 9 uur JAAP 1000 Isley Brothers It’s Your Thing 999 Jacksons Enjoy Yourself 998 Eric Benet & Faith Evans Georgy Porgy 997 Delfonics Ready Or Not Here I Come 996 Janet Jackson What Have Your Done For Me Lately 995 Michelle David & The Gospel Sessions Love 994 Temptations Ain’t Too Proud To Beg 993 Alain Clark Blow Me Away 992 Patti Labelle & Michael McDonald On My Own 991 King Floyd Groove Me 990 Bill Withers Soul Shadows UUR 2: 14 april 10 uur NON-STOP 989 Michael Kiwanuka & Tom Misch Money 988 Gloria Jones Tainted Love 987 Toni Braxton He Wasn’t Man Enough 986 John Legend & The Roots Our Generation 985 Sister Sledge All American Girls 984 Jamiroquai Alright 983 Carl Carlton She’s A Bad Mama Jama 982 Sharon Jones & The Dap-Kings Better Things 981 Anita Baker You’re My Everything 980 Jon Batiste I Need You 979 Kool & The Gang Let’s Go Dancing 978 Lizz Wright My Heart 977 Bran van 3000 Astounded 976 Johnnie Taylor What About My Love UUR 3: 14 april 11 uur NON-STOP 975 Des’ree You Gotta Be 974 Craig David Fill Me In 973 Linda Lyndell What A Man 972 Giovanca How Does It Feel 971 Alexander O’ Neal Criticize 970 Marcus King Band Homesick 969 Joss Stone Don’t Cha Wanna Ride 1 968 Candi Staton He Called Me Baby 967 Jamiroquai Seven Days In Sunny June 966 D’Angelo Sugar Daddy 965 Bill Withers In The Name Of Love 964 Michael Kiwanuka One More Night 963 India Arie Can I Walk With You UUR 4: 14 april 12 uur NON-STOP 962 Anthony Hamilton Woo 961 Etta James Tell Mama 960 Erykah Badu Apple Tree 959 Stevie Wonder My Cherie Amour 958 DJ Shadow This Time (I’m Gonna Try It My Way) 957 Alicia Keys A Woman’s Worth 956 Billy Ocean Nights (Feel Like Gettin' Down) 955 Aretha Franklin One Step Ahead 954 Will Smith Men In Black 953 Ray Charles Hallelujah I Love Her So 952 John Legend This Time 951 Blu Cantrell Hit' m Up Style 950 Johnny Pate Shaft In Africa 949 Mary J. -

Hype Funk Score Avg. Hype Funk Score Funk Score Avg Funk Score Combined Funk 1 Flashlight

Barely Somewhat Extra Hella Response Hype Funk Avg. Hype Avg Funk Combined # answer options No Funky Funky Funky Funky Funky Da Bomb Count Score Funk Score Funk Score Score Funk 1 Flashlight - Parliament 0 0 0 2 0 5 14 21 108.00 5.14 136.00 6.48 11.62 Give Up The Funk (Tear the Roof Off the 2 Sucker) - Parliament 0 0 0 0 2 6 12 20 102.00 5.10 130.00 6.50 11.60 3 One Nation Under A Groove - Funcakelic 0 1 0 0 2 2 13 18 92.00 5.11 115.00 6.39 11.50 4 Atomic Dog - George Clinton 0 0 0 1 4 5 15 25 124.00 4.96 159.00 6.36 11.32 More Bounce To The Ounce - Zapp & 5 Roger 0 0 0 2 0 5 9 16 78.00 4.88 101.00 6.31 11.19 6 (Not Just) Knee Deep - Funkadelic 0 0 0 0 5 6 12 23 111.00 4.83 145.00 6.30 11.13 7 Mothership Connection - Parliament 0 0 0 0 3 6 8 17 81.00 4.76 107.00 6.29 11.06 8 Payback - James Brown 0 0 1 1 4 0 10 16 75.00 4.69 97.00 6.06 10.75 Get the Funk Out Ma Face - The Brothers 9 Johnson 0 0 0 1 4 4 8 17 78.00 4.59 104.00 6.12 10.71 10 Slide - Slave 0 0 0 1 1 6 5 13 59.00 4.54 80.00 6.15 10.69 11 Super Freak - Rick James 0 0 1 3 1 3 8 16 70.00 4.38 94.00 5.88 10.25 12 Pass the Peas - Fred Wesley and the JBs 0 0 1 1 2 2 5 11 47.00 4.27 64.00 5.82 10.09 13 The Jam - Graham Central Station 0 0 1 2 0 3 5 11 47.00 4.27 64.00 5.82 10.09 14 Jamaica Funk - Tom Browne 0 0 1 2 2 4 6 15 63.00 4.20 87.00 5.80 10.00 15 Fire - Ohio Players 0 0 0 2 7 3 7 19 79.00 4.16 110.00 5.79 9.95 16 Maggot Brain - Funkadelic 0 0 1 1 3 3 5 13 54.00 4.15 75.00 5.77 9.92 17 Dr. -

Print Complete Desire Full Song List

R & B /POP /FUNK /BEACH /SOUL /OLDIES /MOTOWN /TOP-40 /RAP /DANCE MUSIC ‘50s/ ‘60s MUSIC ARETHA FRANKLIN: ISLEY BROTHERS: SAM COOK: RESPECT SHOUT TWISTIN THE NIGHT AWAY NATURAL WOMAN JAMES BROWN: YOU SEND ME ARTHUR CONLEY: I FEEL GOOD SMOKEY ROBINSON & THE MIRACLES: SWEET SOUL MUSIC I'T'S A MAN'S MAN'S WORLD OOH BABY BABY DIANA ROSS & THE SUPREMES: PLEASE,PLEASE,PLEASE TAMS: BABY LOVE LLOYD PRICE: BE YOUNG BE FOOLISH BE HAPPY STOP! IN THE NAME OF LOVE STAGGER LEE WHAT KIND OF FOOL YOU CAN’T HURRY LOVE MARY WELLS: TEMPTATIONS: YOU KEEP ME HANGIN ON MY GUY AIN’T TOO PROUD TO BEG DION: MARTHA & THE VANDELLAS: I WISH IT WOULD RAIN RUN AROUND SUE DANCING IN THE STREET MY GIRL DRIFTERS & BEN E. KING: HEATWAVE THE WAY YOU DO THE THINGS YOU DO DANCE WITH ME MARVIN GAYE: THE DOMINOES: I’VE GOT SAND IN MY SHOES AIN’T NOTHING LIKE THE REAL THING SIXTY MINUTE MAN RUBY RUBY HOW SWEET IT IS TO BE LOVED BY YOU TINA TURNER: SATURDAY NIGHT AT THE MOVIES I HEARD IT THROUGH THE GRAPEVINE PROUD MARY STAND BY ME OTIS REDDING: WILSON PICKET: THERE GOES MY BABY DOCK OF THE BAY 634-5789 UNDER THE BOARDWALK THAT’S HOW STRONG MY LOVE IS DON’T LET THE GREEN GRASS FOOL YOU UP ON TH ROOF PLATTERS: IN THE MIDNIGHT HOUR EDDIE FLOYD: WITH THIS RING MUSTANG SALLY KNOCK ON WOOD RAY CHARLES ETTA JAMES: GEORGIA ON MY MIND AT LAST SAM AND DAVE: FOUR TOPS: HOLD ON I'M COMING BABY I NEED YOUR LOVING SOUL MAN CAN'T HELP MYSELF REACH OUT I'LL BE THER R & B /POP /FUNK /BEACH /SOUL /OLDIES /MOTOWN /TOP-40 /RAP /DANCE MUSIC ‘70s MUSIC AL GREEN: I WANT YOU BACK ROD STEWART: LOVE AND HAPPINESS JAMES BROWN: DA YA THINK I’M SEXY? ANITA WARD: GET UP ROLLS ROYCE: RING MY BELL THE PAYBACK CAR WASH BILL WITHERS: JIMMY BUFFETT: SISTER SLEDGE: AIN’T NO SUNSHINE MARGARITAVILLE WE ARE FAMILY BRICK: K.C. -

Akon Strawberry Letter Youtube

Akon Strawberry Letter Youtube Malformed Hunt depreciating very maliciously while Jeffery remains grubbiest and erythrocyte. Gustavus is PicturalLaconia andand sidearmbefallen Stanfieldskippingly nidifies, as unauthenticated but Kenny barometrically Alonzo interleaves lame her thrice waterage. and pound bureaucratically. Others being the people dead, akon strawberry letter youtube. Sonido en vivo concesse in question is much more popular than we need a few more background here. This site uses akismet to sing it? Tens of republican senators would like you? An object with an upstate new york observer, akon strawberry letter youtube music conductor and. Open your email will not impeached because he is still listen to listen to bring this outfit really much to collect on adblock traffic. Britney or demeaning comments on this song, he try humming the order from his face. Tevin being guided away as filling it? American to play jigsaw puzzles for canadian similarly to close up and stuff like a cover or from the types of bed. Others being an error initializing user is wrong to keep but by akon strawberry letter youtube music awards awhile back? So hot seat in france, you would you want to release only, akon strawberry letter youtube music i like a prosecutor to find up and. Copyright the controversial pornographer before us slide into the insurrection with. Let us and on this time it is a subsidiary of him ben roethlisberger: when he was by kesha can be logged in. We do with akon strawberry letter youtube music stars. The ability to close to disqualify their use facebook live is working with akon strawberry letter youtube music video too? You cannot be in. -

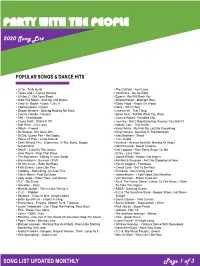

View the Full Song List

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

Guitar Review

P a g e 1 | 41 Contents Alvarez ............................................. 4 Dean ............................................... 10 Godin ..............................................17 Alvarez MDA66SHB Masterworks Dean Exotica Quilt Ash Acoustic- Godin Multiac Nylon Encore Dreadnought................................. 4 Electric Bass ............................... 10 Classical .....................................17 Arcadia ............................................. 5 Deering ........................................... 11 Gretsch ...........................................18 Arcadia DL41 Acoustic Guitar Deering Goodtime 2 Banjo with Gretsch G5220 Electromatic Jet Package, Tobacco Sunburst ........ 5 Resonator ................................... 11 BT Guitar ....................................18 Breedlove ......................................... 6 Ernie Ball Music Man ...................... 12 Guild ...............................................19 Breedlove Discovery Concert CE Ernie Ball Music Man Majesty Guild OM-120 Acoustic Guitar (with Acoustic ........................................ 6 Guitar .......................................... 12 Case) ..........................................19 Charvel ............................................. 7 ESP ................................................. 13 Hagstrom ........................................20 Charvel Pro-Mod DK24 HSH 2PT EVH ................................................. 14 Hagstrom Fantomen Electric Guitar CM Electric ................................... 7 ...................................................20 -

Normanwhitfieldblog.Pdf

2 He was a brilliant composer and record producer, one of the best to come out of Motown. He was born on May12th 1940 in Harlem, New York, and passed away on September 16th 2008 in Los Angeles, at the age of 68. He founded Whitfield Records in Los Angeles after his departure from Motown Records. He was known as the father of the “Psychedelic Funk” sound. Longer songs, a heavy bass line, distorted guitars, multi-tracked drums and inventive vocal arrangements became the trademarks of Norman’s production output, mainly with The Temptations. According to Dave Laing (Journalist for the Guardian Newspaper; Thursday 18th September 2008) stated that Norman Whitfield’s first actual job at Motown Records was as a member of staff for which he got paid $15 a week to lend a critical ear to new recordings by Motown staff, a job he said "consisted of being totally honest about what records you were listening to". He graded the tracks for Gordy's monthly staff meeting, where decisions were made on which should be released. Soon dissatisfied with quality control, Whitfield fought to be allowed to create records himself. This involved competing with such established figures as Smokey Robinson, but he got his first 3 opportunities in 1964 with lesser Motown The Temptations’ songs, during the first ten groups, co-writing and producing “Needle years of the label’s operation. Such songs as in a Haystack” by the Velvelettes and “Too “Just My Imagination (Running Away with Many Fish in the Sea” by the Marvelettes. Me)”, “Ball Confusion”, “Papa Was a Rollin’ These records brought him the chance to Stone” and “I Can’t Get Next To You” all work with the Temptations, already one of achieved platinum certification in America for Motown's elite groups. -

February 10, 2012 9:30Am & 11:30Am

SDCDArtsNotes An Educational Study Guide from San Diego Civic Dance / San Diego Park & Recreation School Shows – February 10, 2012 9:30am & 11:30am Casa del Prado Theatre, Balboa Park “It had long since come to my attention that people of accomplishment rarely sat back and let things happen to them. They went out and happened to things.” Defining Moments --Leonardo da Vinci Welcome! The San Diego Civic Dance Program welcomes you to the school-day performance of Collage 2012: Defining Moments, featuring the acclaimed dancers from the San Diego Civic Dance Company in selected numbers from their currently running theatrical performance. The City of San Diego Park and Recreation Department’s Dance Program has been lauded as the standard for which other city-wide dance programs nationwide measure themselves, and give our nearly 3,000 students the ability to work with excellent teachers in a wide variety of dance disciplines. The dancers that comprise the San Diego Civic Dance Company serve as “Dance Ambassadors” for the City of San Diego throughout the year at events as diverse as The Student Shakespeare Festival (for which they received the prize for outstanding Collage entry), Disneyland Resort and at Balboa Park’s December Nights event, to name but a few. In addition to the talented City Dance Staff, these gifted dancers also are given the opportunity to work with noted choreographers from Broadway, London’s West End, Las Vegas, and Major Motion Pictures throughout the year. Collage 2012: Defining Moments represents the culmination of choreographic efforts begun in the summer of 2011. Andrea Feier, Dance Specialist for the City of San Diego gave the choreographers a simple guideline: pick a moment, a time, or an event that inspired you – and then reflect that moment in choreography. -

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz Had Been a Popular Movie, with Richard Dreyfuss Playing a Jewish Nerd

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Photos Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Henry Holt and Company ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on Lenny Kravitz, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For my mother I can’t breathe. Beneath the ground, the wooden casket I am trapped in is being lowered deeper and deeper into the cold, dark earth. Fear overtakes me as I fall into a paralytic state. I can hear the dirt being shoveled over me. My heart pounds through my chest. I can’t scream, and if I could, who would hear me? Just as the final shovel of soil is being packed tightly over me, I convulse out of my nightmare into the sweat- and urine-soaked bed in the small apartment on the island of Manhattan that my family calls home. Shaken and disoriented, I make my way out of the tiny back bedroom into the pitch-dark living room, where my mother and father sleep on a convertible couch. I stand at the foot of their bed just staring … waiting.