Kraf Tunion Network 02102011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sysco Cheese Product Catalog

> the Sysco Cheese Product Catalog Sysco_Cheese_Cat.indd 1 7/27/12 10:55 AM 5 what’s inside! 4 More Cheese, Please! Sysco Cheese Brands 6 Cheese Trends and Facts Creamy and delicious, 8 Building Blocks... cheese fi ts in with meal of Natural Cheese segments during any Blocks and Shreds time of day – breakfast, Smoked Bacon & Cheddar Twice- Baked Potatoes brunch, lunch, hors d’oeuvres, dinner and 10 Natural Cheese from dessert. From a simple Mild to Sharp Cheddar, Monterey Jack garnish to the basis of and Swiss a rich sauce, cheese is an essential ingredient 9 10 12 A Guide to Great Italian Cheeses Soft, Semi-Soft and for many food service Hard Italian Cheeses operations. 14 Mozzarella... The Quintessential Italian Cheese Slices, shreds, loaves Harvest Vegetable French and wheels… with Bread Pizza such a multitude of 16 Cream Cheese Dreams culinary applications, 15 16 Flavors, Forms and Sizes the wide selection Blueberry Stuff ed French Toast of cheeses at Sysco 20 The Number One Cheese will provide endless on Burgers opportunities for Process Cheese Slices and Loaves menu innovation Stuff ed Burgers and increased 24 Hispanic-Style Cheeses perceived value. Queso Seguro, Special Melt and 20 Nacho Blend Easy Cheese Dip 25 What is Speciality Cheese? Brie, Muenster, Havarti and Fontina Baked Brie with Pecans 28 Firm/Hard Speciality Cheese Gruyère and Gouda 28 Gourmet White Mac & Cheese 30 Fresh and Blue Cheeses Feta, Goat Cheese, Blue Cheese and Gorgonzola Portofi no Salad with 2 Thyme Vinaigrette Sysco_Cheese_Cat.indd 2 7/27/12 10:56 AM welcome. -

Safe Snack List

Commonly Available Snacks Free of Peanuts, Tree Nuts and Eggs Content Updated: October 15, 2015 Halloween Edition This copy was downloaded: October 20, 2015 Do not use this copy after: November 2, 2015 After this date, download an updated copy from: snacksafely.com/download Please read and understand this entire page before using this guide. Your use of this guide indicates that you have read and understand the disclaimer below and accept and agree to its limitations. DISCLAIMER: ALL INFORMATION REGARDING INGREDIENTS AND MANUFACTURING PROCESSES WERE COMPILED FROM CLAIMS MADE BY THE PRODUCTS’ RESPECTIVE MANUFACTURERS ON THEIR LABELS OR VIA OTHER MEANS AND MAY ALREADY BE OUT OF DATE. ALTHOUGH EVERY EFFORT HAS BEEN MADE TO BE AS ACCURATE AS POSSIBLE, WE DO NOT ACCEPT ANY LIABILITY FOR ERRORS OR OMISSIONS MADE BY US OR THE PRODUCTS’ RESPECTIVE MANUFACTURERS. THIS LIST IS FOR INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY AND IS INTENDED TO SERVE AS A GUIDE, NOT AS AN AUTHORITATIVE SOURCE, AND IS NOT INTENDED TO REPLACE THE ADVICE OF ANY MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL. PRIOR TO PURCHASING ANY LISTED FOOD ITEM, IT IS YOUR RESPONSIBILITY TO CHECK THE PRODUCT LABEL TO ENSURE THAT UNDESIRED ALLERGENS ARE NOT LISTED AS INGREDIENTS AND TO VERIFY WITH THE MANUFACTURER THAT TRACE AMOUNTS OF UNDESIRED ALLERGENS WERE NOT INTRODUCED DURING THE MANUFACTURING PROCESS. CURRENT FDA LABELING GUIDELINES DO NOT MANDATE MANUFACTURERS DISCLOSE POTENTIAL ALLERGENS THAT MAY BE INTRODUCED AS PART OF THE MANUFACTURING PROCESS. Meaning of the symbols: For items preceeded by green symbols, the information was provided by the manufacturer on their packaging, promotional literature, website, or directly to us. -

Kraft Foods Inc(Kft)

KRAFT FOODS INC (KFT) 10-K Annual report pursuant to section 13 and 15(d) Filed on 02/28/2011 Filed Period 12/31/2010 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 (Mark one) FORM 10-K [X] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2010 OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 1-16483 Kraft Foods Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 52-2284372 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) Three Lakes Drive, Northfield, Illinois 60093-2753 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: 847-646-2000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Class A Common Stock, no par value New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes x No ¨ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x Note: Checking the box above will not relieve any registrant required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Exchange Act from their obligations under those Sections. -

Enel Green Power's Renewable Energy Is Part of the History of Mondelēz International's Business Unit in Mexico

Media Relations T (55) 6200 3787 [email protected] enelgreenpower.com ENEL GREEN POWER'S RENEWABLE ENERGY IS PART OF THE HISTORY OF MONDELĒZ INTERNATIONAL'S BUSINESS UNIT IN MEXICO • Enel Green Power supplies up to 77 GWh annually to two Mondelēz International factories with wind energy from its 200 MW Amistad I wind farm located in Ciudad Acuña, Coahuila. • Thanks to this relationship, Mondelēz International has avoided the emission of approximately 33,000 tons of CO2 per year. Mexico City, October 7th, 2020 – Enel Green Power México (EGPM), the renewables subsidiary of Enel Group, joins the celebration of the 8th anniversary of Mondelēz International in the country, by commemorating two years of successful collaboration through an electric power supply contract. Derived from this contract, Mondelēz International has received up to 77 GWh per year of renewable energy to its factories located in the State of Mexico and Puebla. Thanks to the renewable energy supplied by EGPM´s Amistad I wind farm; Mondelēz International has avoided the emission of around 33,000 tons of CO2 per year, equivalent to almost 80% of its emission reduction target for Latin America in 2020. Similarly, this energy is capable of producing approximately more than 100,000 tons annually of product from brands such as Halls, Trident, Bubbaloo, Oreo, Tang and Philadelphia and is enough to light approximately 33,000 Mexican homes for an entire year. “It is an honor for Enel Green Power México to contribute to Mondelēz International environmental objectives and efforts to accelerate energy transition in the country. Today more and more companies are convinced that renewable energies are not only sustainable, but also profitable, which is why this type of agreements serve as a relevant growth path for clean sources in Mexico”, stated Paolo Romanacci, Country Manager of Enel Green Power Mexico. -

$4.69Lb $3.49Lb $2.59Lb $6.99Lb

WHAt Perch’s WAS BUILT ON... PUREST, FRESHEST MEAT PRODUCTS EVERYDAY! Beer & Wine Take Out • Packaged Liquor Dealer • We accept U.S.D.A. Food Stamps & WIC Program • We Sell Michigan State Lottery & Lotto Tickets Summer Hours: Check out our Mon.-Sat. 7am-9pm Perch’s Weekly Ad online! Perch’sPRICES EFFECTIVE: Sun. 8am-7pm Monday August 31 to Sunday Sept. 06, 2020 Visit PERCHSIGA.COM 1025 Hwy. U.S. 23 N. • (989) 354-4012 Make Labor Day Delicious! USDA Choice 95% Extra Lean Star Ranch Ground Beef Angus Top From Round $ Sirloin Steak LB $ 4.69 6.99 LB Perch’s Famous 85% Lean Ground Beef from Chuck 10 LB Bulk Bag Lesser Amounts $ 79 $4.19 LB 3 LB Perch’s Perch’s Famous Specialty Patties Seafood (Mushroom & Swiss or Polish Sausage Jalapeno & Cheddar) $ $ Favorites 3.49 LB 4.99 LB this Clearly $ 99 Week! Sockeye Salmon 12 oz. 7 Plath’s Cornish Smoked Picnic Hens 2 pk. 48 oz. Best Choice Louis Kemp 2/$ Ham Shrimp Rings $ 99 Imitation Crab 4 $ 5 Leg Meat 8 oz. $ pkg. 10 oz. 2.59 LB 4.99 Produce 5/$ $ 99 $ 79 ¢ $ 99 3/$ 2 2 1 59 LB 3 EA 5 Michigan Michigan Yellow Green Whole Seedless Blueberries Sweet Corn Red Potatoes Cooking Onions Cabbage Watermelon pint (in the husk) 5 lb. bag 3 lb. bag 2/$ ¢ ¢ 2/$ ¢ $ 99 6 99 EA 69 LB 7 99 EA 6 EA Blackberries or Baby Carrots Michigan Hard Jumbo Dole Coleslaw Sunlint Meadow Raspberries 1 lb. bag Shell Squash Russet Potatoes 14 oz. -

L O W P R Ices E V Er Y S in Gle D A

LOW PRICES EVERY SINGLE DAY! SINGLE EVERY PRICES LOW PRICES VALID WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 5–TUESDAY, AUGUST 11, 2020 – OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK: 7A.M.–10P.M. – $ 49 ¢ 2 ea 77 lb Oscar Mayer Market Wrapped Deli Shaved Lunch Meats Family Pack 7-9 oz. Chicken Drumsticks $699 $149 $199 $299 ea ea ea ea Cacique Oscar Mayer Jennie-O 85% Lean Jennie-O Ranchero Queso Fresco Fun Pack Lunchables Ground Turkey Chub or Tray Jumbo Turkey Franks Kilo 8-11 oz. 16 oz. 48 oz. $ 99 $ 88 1 ea 1 ea ¢ 77 Dr Pepper, RC Cola, Crisp ea 7-Up, Squirt, Diet The Original Iceberg Cello Dr Pepper or Big Red Bomb Pop Head Lettuce 6 pk., .5 ltr. Btls. 12 ct. Pkg. YOURFOODTOWN.COM We reserve the right to limit quantities. Selection varies by store. Check out all the specials on these pages Produce 2-3 Grocery 4-8 Conagra 9 Dairy/Frozen 10 Beverages 11 Household 12 Meat 13-20 1 Food Town_080520_1 8/5 PRODUCE Spcials $ 79 1 8 oz. Pkg. Dole Spinach ¢ $ 29 39 lb Fresh 1 1 lb. Green Cabbage Bag 2 $ 4 $ Crisp – FOR – 1 – FOR – 1 Baby Carrots ¢ 99 ea Sweet Juicy Juicy Mangos Yellow Lemons Crisp ¢ ¢ Celery 99 ea 69 lb ¢ 39 lb Fresh Mild Large Bunch Fresh Radishes Green Tomatillos White Onions Food Town_080520_2 2 8/5 PRODUCE ¢ ¢ 89 lb 89 lb Red Ripe Fresh Roma Tomato White Potato $ 29 ¢ 1 lb 79 lb Mild Spicy Green Poblano Peppers Jalapeño Peppers ¢ $ 99 89 lb 1 24 ct. Pkg Crisp Yuca Root Fun Pops Ice Pops $ 99 $ 29 2 28 oz 2 4 oz Bag Pkg Goya Nacho Tortilla Chips Plantain Chips 3 Food Town_080520_3 8/5 GROCERY Spcials Spcials $ 99 $ 77 1 ea 1 ea Downy Fabric Softener (64 oz. -

Val's “Recipe Box”

Val’s “Recipe Box” 4/18/19 As a former Home Economics teacher, AgVantage Customer Services Representa- tive Valerie Ahlers has accumulated a huge assortment of delicious recipes! In addition to her former career as a teacher, she is a farm wife and mother and has cooked for many people her entire life. She makes treats for all AgVantage Soft- ware staff on their birthdays and in general, spoils us all on a regular basis and we love it! In March, 2019, Val was honored to be a recipient of the Community Service Award from the Minnesota Grain & Feed Association. It was granted for her many hours of lifetime volunteerism with the SE Minnesota Grain Dealers Association and many other groups. Congratulations Val! Val has been sharing her recipes regularly with her fellow AgVantage employees and her customers in our company newsletter since 2005. Occasionally, other staff members have also contributed to this recipe collection. After repeated customer requests for recipes that had appeared in old newsletters, we decided to make them all accessible on our website, in sort of a cookbook. Yes, we are a technology company, but we still all have an appreciation for great food! We hope you enjoy her recipes! Lori Campbell Retired Conference Manager AgVantage Software, Inc. INDEX of Newsletter Recipes —The Recipes appear in this book in the order in which they were featured in the AgVantage Newsletter Appetizers Desserts Bonnie’s Guacamole Page 5 Raw Apple Cake Page 3 Deluxe Crispix Mix Page 6 Pumpkin Pie Squares Page 4 Cabbage Salsa Page 15 Caramel -

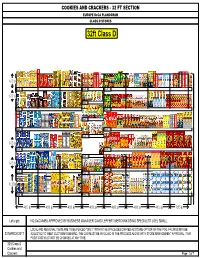

Cookies and Crackers CPI WORKING.Psa COOKIES and CRACKERS - 32 FT SECTION

COOKIES AND CRACKERS - 32 FT SECTION EUROPE DeCA PLANOGRAM CLASS D STORES 32ft Class D 440 000 44000 4400004325 447 440 440 04324 RITZ 4 000 000 440 RITZ TOASTED NAB 435 435 000 TOAS CORN ISC 5 4 448 TED CHIPS 8.12 in O BEL BEL 6 COR SALSA OR VIT VIT NAB N VERDE K4 EO A A ISC CHIP Shelf: 1 Shelf: 7 Shelf: 14 6.12 in Shelf: 8 Shelf: 2 Shelf: 15 440000 4454 440000 440000 NABIS 4913 4914 30100 440 440 440 CO NABIS NABIS 11096 Shelf: 9 000 000 000 OREO CO CO KEEBL 454 454 426 RED CHIPS CHIPS ER 5 6 9 VELVE AHOY AHOY COOKI NAB NAB NAB T THINS THINS ES ISC ISC ISC Shelf: 3 Shelf: 16 301001 301001 1147 1299 KEEBL KEEBL Shelf: 10 ER ER COOKI COOKI ES ES 6.12 in EL EL FUDG FUDG Shelf: 4 Shelf: 17 Shelf: 11 6.12 in Shelf: 18 Shelf: 5 Shelf: 12 44000047 17 NABISCO HONEY MAID 11.12 in GRAHAM S FAMILY K1 Shelf: 6 Shelf: 13 Shelf: 19 4 ft 1 in 4 ft 1 in 4 ft 1 in 4 ft 1 in 4 ft 1 in 4 ft 1 in 4 ft 1 in 3 ft 5 in Left-right HQ DeCA/MBU APPROVED BY BUSINESS MANAGER DAVID LEFFERT MERCHANDISING SPECIALIST JOEL SMALL. LOCAL AND REGIONAL ITEMS ARE TO BE PLACED "ONLY" WITHIN THE SPACE DESIGNATED AS STORE OPTION ON THE POG. FACINGS MAY BE 23 MARCH 2017 ADJUSTED TO MEET CUSTOMER DEMAND. -

Gum * Bubble/Kids/Novelty Types- (0200) Gum * Mini Packs

PAGE : 1 SOLD TO CUST NO. DATE : _______________ GUM * BUBBLE/KIDS/NOVELTY TYPES- (0200) 360959 TRIDENT GUM S/F ISLAND BERRY 12/BX 530324 AIRHEAD GUM BL RASPBERRY 14PC 12/BX 360906 TRIDENT GUM S/F MINT BLISS 12/BX 530320 AIRHEAD GUM CHERRY 14 PC 12/BOX 360913 TRIDENT GUM S/F MINT SW TWST 12/BOX 530322 AIRHEAD GUM WATERMELON 14 PC 12/BOX 360951 TRIDENT GUM S/F ORIGINAL 12/BOX 350250 BIG LEAGUE CHEW GRAPE 12/BOX 361003 TRIDENT GUM S/F PASSION FRT 12/BOX 350202 BIG LEAGUE CHEW GIRL 12/BOX 360919 TRIDENT GUM S/F PEPPERMINT 12/BOX 350200 BIG LEAGUE CHEW ORIGINAL 12/BOX 360901 TRIDENT GUM S/F SPEARMINT 12/BOX 350170 BIG LEAGUE CHEW SOUR APPLE 12/BOX 360911 TRIDENT GUM S/F TROPIC TWIST 12/BX 350160 BIG LEAGUE CHEW WATERMELON 12/BOX 360957 TRIDENT GUM S/F WINTERGREEN 12/BOX 350174 BIG LEAGUE CHEW 5-BALL GRAPE 18/BOX 360962 TRIDENT GUM S/F WTR/MLN TWIST 12/BX 350176 BIG LEAGUE CHEW 5-BALL ORIG 18/BX 361031 TRIDENT LAYERS CHERRY + LIME 12/BX 750300 BUBBLE TAPE BUBBLE GUM 24/BOX 361026 TRIDENT LAYERS GRAPE+LEMONADE 12/BX 350400 BUBBLE YUM REGULAR 18/BOX 361020 TRIDENT LAYERS SBERRY/CITRUS 12/BX 350778 BUBBLICIOUS BUBBLE GUM 18/BOX 361035 TRIDENT LAYERS W-MELON/TROPIC 12/BX 350710 BUBBLICIOUS GONZO GRAPE 18/BOX 326001 WRIG "5" ASCENT PTP 10/BX 350900 BUBBLICIOUS S/BERRY SPLASH 18/BOX 326010 WRIG "5" COBALT PTP 10/BX 350950 BUBBLICIOUS WATERMELON 18/BOX 327040 WRIG "5" PRISM WATERMELON PTP 10/BX 351030 HUBBA BUBBA MAX SB/WM 18/BOX 326020 WRIG "5" RAIN PTP 10/BX 351015 HUBBA BUBBA ORIGINAL 18/BOX 328005 WRIG "5" REACT MINT PTP 10/BX 351452 RAINBLO -

2/$4 2.99 1.79 1.99 .99 3/$2 2/$4 2/$3 6.99 2.99 2.99 3/$5 2/$5 .99

22-30 Oz. 14-16 Oz. 17.5-18 Oz. 32 Oz. Kraft Kraft Kraft Kraft Mayonnaise Salad Dressing Barbecue Sauce Velveeta Loaf 2.99 3/$5 .99 6.99 9.4-14 Oz. Kraft Deluxe 22-36.8 Oz. 22-30 Oz. 10 Oz. Macaroni & Cheese Maxwell House Kraft A.1. or Velveeta Shells & Ground Coffee Miracle Whip Steak Sauce Cheese Dinners 6.99 2.99 2/$5 2.25 Makes 6-10 Quarts or 10-12 Ct. 10 Oz. 8.4-10.1 Oz. Country Time, Tang, 8-14 Oz. Kraft Jet-Puffed Jell-O Creations Kool-Aid or Crystal Light Heinz Marshmallows Dessert Kits Drink Mixes Mustard .99 2.29 2/$4 2/$3 .8-3.9 Oz. .3-3 Oz. Jell-O 16-20 Oz. 31-38 Oz. Jell-O or Kool-Aid Pudding & Pie Planters Dry Roasted Heinz Gelatin Dessert Filling or Cocktail Peanuts Ketchup 3/$2 3/$2 2.99 2/$5 7 Oz. 16 Oz. 7-8 Oz. Cool Whip Breakstone’s Cracker Barrel Chunk Dessert Topping Sour Cream or Cracker Cuts Cheese 2/$4 1.99 2/$6 5-8 Oz. Kraft Chunk, 7-8 Oz. 8 Oz. 12 Oz. Kraft Natural or Kraft Philadelphia Kraft Shredded, Cubes, Crumbles or Cheese Cracker Barrel Cream Cheese American Singles Cracker Cuts Sliced Cheese 2/$3 2/$4 1.79 1.99 PMG PMG_BASE_FT_INSERT_062616 20-60 Ct. 12-36 Ct. 18-20 Ct. Hefty Everyday 8.3 Lb. Chinet Plates, IGA Plastic Plates, Bowls IGA Regular Platters or Bowls Party Cups or Platters Charcoal 2/$6 .99 3/$5 2.99 40-250 Ct. -

AUG 2020 Lil’Drug Sanitizer Display

AUG 2020 Lil’Drug SAnitizer DisplAy Qty BWG # Description Pack Size Cost Unit Cost SRP Margin Total Retail Gross Profit Lil Drug Personal Protection Display 66 COUNT $91.52 49% $179.28 $ 87.76 Lil Drug Hand Sanitizer 36 1.5 OZ $36.44 $1.01 $1.99 49% $71.64 $ 35.20 Lil Drug Antibacterial Hand Wipes 36 30 CT $55.08 $1.53 $2.99 49% $107.64 $ 52.56 Customer#: ________________ Customer Name: ______________________________________________ *Prices subject to change SHIP DATES: SEPT 21. 2020 Pre-Book today VAlentine’s SnAcks $1.00 Qty BWG # Description Pack Size Cost Deal Net Cost Unit Cost SRP Margin Total Retail Gross Profit 997-252 Hostess Valentine Counter Display 32 CT $37.70 $1.00 $36.70 $1.15 $1.89 39% $60.48 $ 23.78 Customer#: ________________ Customer Name: ______________________________________________ *Prices subject to change SHIP DATES: JAN 2021 Pre-Book today EAster CAndy $2.83 EAster is SundAy, April 4, 2021 Qty BWG # Description Pack Size Cost Deal Net Cost Unit Cost SRP Margin Total Retail Gross Profit 994-505 M&M'S Mini Milk Chocolate Mega Tubes 24 1.77 OZ $30.78 $2.83 $27.95 $1.16 $1.99 41% $47.76 $ 19.81 994-530 Snickers Eggs 2 To Go 24 2.83 OZ $30.78 $2.83 $27.95 $1.16 $1.99 41% $47.76 $ 19.81 994-513 M&M'S Peanut Butter Speckled Egg Share Size 24 2.83 OZ $30.78 $2.83 $27.95 $1.16 $1.99 41% $47.76 $ 19.81 994-501 M&M'S Pastel Peanut Share Size 24 3.27 OZ $30.78 $2.83 $27.95 $1.16 $1.99 41% $47.76 $ 19.81 994-804 Starburst Jelly Beans Share Size 15 3.6OZ $19.31 $1.77 $17.54 $1.17 $1.99 41% $29.85 $ 12.31 994-508 M&M'S White -

Brummies Have Spoken Loudly and Opt for Wispa in Battle of Cadbury

Brummies have spoken loudly and opt for Wispa in battle of Cadbury Heroes at Christmas • Survey finds Wispa is Birmingham’s Hero of Cadbury Heroes • The Hazel Whirl is the Rose of all Roses, with Hazel in Caramel also scoring highly • Almost two-thirds of Birmingham adults believe Christmas isn’t complete without chocolate To mark 20 years since Cadbury’s Heroes hit our store selves and entered our annual Christmas gifting traditions, Mondelēz International, maker of the some of the UK’s best loved brands including Cadbury, Oreo and Maynards Bassets, has revealed the official consumer rankings of Cadbury Heroes and Roses, as decided by the Birmingham public. Mondelēz International worked with YouGov to ask Brits to pick their favourite from a box of Cadbury Heroes and Cadbury Roses, with the results sure to spark a debate. In what many may consider a surprise result, Wispa proved to be Birmingham’s favourite selection from a box of Cadbury Heroes, taking the top spot and a place in the city’s heart (and belly). Despite its place in British and Birmingham culture, the UK’s favourite chocolate1, Cadbury Dairy Milk, had to settle for second place in the official rankings, pushing Cadbury Dairy Milk Caramel in to third place. Eclairs are the last to be eaten and last in the standings, however it’s a close call between all options, including more recent addition additions, Dinky Decker and Creme Egg Twisted. Tastes appear to vary across the country, with the UK as a whole plumping for Crunchie and Twirl as their top Heroes of choice, with Birmingham’s favourite coming in fourth place nationally.