Factors That Influence the Provision of Intrapartum and Postnatal Care By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LMIC Databases August 2013

LMIC Databases August 2013 A collection of databases, web sites and journals relevant to Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) This list has been put together in a collaborative effort by Cochrane Groups, the WHO Library and volunteers outside the Cochrane Collaboration. Please click the navigation pane to see the list content. For information on how the list has developed, please see the history note at the bottom of this document. Any comments you might have to the list, or suggestions for additional resources, will be most welcome. Contact person: [email protected] Global Databases 3ie Database of Impact Evaluations URL http://www.3ieimpact.org/en/evidence/ Provider 3ie Region Global – low and middle income countries Description Covers impact evaluations conducted in low- and middle- income countries. Search language English Format Web Content language English Content Impact evaluation studies Draws from a wide range of sources (22 databases and 12 research web sites) including grey literature To be included, the study must meet 3ie’s quality standards. MEDLINE overlap Unclear Database size Circa 750 publications [February 2013] Journals indexed Not applicable. Individual papers included Other items indexed Unclear Update frequency Unclear Search options Basic keyword (single box) and advanced search. Search function Advanced search has options to search within title, author, country, region, sector (topic), vulnerable groups, evaluation method (eg experimental, quasi-experimental), status (eg ongoing, published) and whether or not there is a gender focus. Search tips Can search for single terms or phrases. Does not appear to support Boolean logic as yet. Search example Text words in basic search (keywords) and words in title/author boxes plus drop down boxes in advanced search (see search function). -

Report on Strengthening Research Capacities for Health in the Caribbean, 2007–2017 Executive Summary Iii

Executive Summary i REPORT ON STRENGTHENING RESEARCH CAPACITIES FOR HEALTH IN THE CARIBBEAN 2007-2017 ii Report on Strengthening Research Capacities for Health in the Caribbean, 2007–2017 Executive Summary iii REPORT ON STRENGTHENING RESEARCH CAPACITIES FOR HEALTH IN THE CARIBBEAN 2007-2017 Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) Office of Knowledge Management, Bioethics and Research (KBR) Secretariat to the Advisory Committee on Health Research Washington, D.C. 2017 iv Report on Strengthening Research Capacities for Health in the Caribbean, 2007–2017 Report on Strengthening Research Capacities for Health in the Caribbean, 2007-2017 Document Number: PAHO/KBR/17-021 © Pan American Health Organization, 2017 All rights reserved. Publications of the Pan American Health Organization are available on the PAHO website (www.paho.org). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate PAHO Publications should be addressed to the Communications Department through the PAHO website (www.paho.org/ permissions). Suggested citation: Pan American Health Organization. Report on Strengthening Research Capacities for Health in the Caribbean, 2007-2017. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 2017. Available at http://iris.paho. org/xmlui/handle/123456789/34342. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data: CIP data are available at http://iris.paho.org. Publications of the Pan American Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Pan American Health Organization concerning the status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Ii. Grenada Health System: National and Regional Structures and Influences 22

Acknowledgements This “Rapid Assessment of Sexual and Reproductive Health and HIV Policy, This report is a Systems and Services in Grenada” was undertaken by the United Nations product of the Population Fund (UNFPA) in collaboration with the Ministry of Health of United Nations Grenada from August to November 2010. Population Fund (UNFPA)/ Sub- Sincere thanks and appreciation are extended to all persons interviewed and Regional Office for involved in the process of data collection for this report, particularly Senator the Caribbean. It the Hon. Ann Peters, Minister of Health, for securing representatives of was prepared by Ms the Ministry to oversee country coordination of data collection and report Cherise Adjodha, reviewing processes; Dr. George Mitchell, Senior Medical Officer, who was Consultant, on appointed as the Ministry of Health focal point, for coordination of all Ministry- behalf of UNFPA. related interviews and site visits; and Dr. Alister Antoine, Medical Officer of Health, for overseeing coordination of the national stakeholder consultation OCTOBER 2011 held to review and validate the report’s findings and recommendations. UNFPA also acknowledges the assistance of all respondents and staff of the following agencies and organizations: Ministry of Health Ministry of Education Grenada Council for the Disabled Legal Aid and Counselling Clinic (LACC) Ministry of Social Affairs Hope Pals Foundation Grenada National Organisation of Women (GNOW) Grenada Planned Parenthood Association National AIDS Council Grenada/Caribbean HIV/AIDS Partnership (GrenCHAP) Child Welfare Authority Ministry of Legal Affairs Grenada Community Development Agency (GRENCODA) United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Sub-Regional Office for the Caribbean/Barbados UN House Marine Gardens, Hastings, Christ Church, Barbados TABLES, FIGURES AND BOXES 1 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 3 INTRODUCTION 6 1. -

2.3 Latin America & the Caribbean

Regional Overview 2.3 Latin America & the Caribbean 99 2.3 LATIN AMERICA & THE CARIBBEAN ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA ARGENTINA THE BAHAMAS BOLIVIA BARBADOS BRAZIL BELIZE COLOMBIA BERMUDA COSTA RICA CUBA CHILE DOMINICA ECUADOR DOMINICAN REPUBLIC EL SALVADOR GRENADA GUATEMALA GUYANA HONDURAS HAITI MEXICO JAMAICA NICARAGUA PUERTO RICO PANAMA SAINT KITTS AND NEVIS PARAGUAY SAINT LUCIA PERU SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES URUGUAY SURINAME VENEZUELA TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO 100 Global State of Harm Reduction 2020 TABLE 2.3.1: Epidemiology of HIV and viral hepatitis, and harm reduction responses in the Latin America and the Caribbean Country/ People who HIV Hepatitis C Hepatitis B Harm reduction response territory with inject drugs prevalence (anti-HCV) (anti-HBsAg) reported injecting among prevalence prevalence Peer drug use1 people who among among distribution inject drugs people who people who NSP2 OAT3 DCRs4 of (%) inject drugs inject drugs naloxone (%) (%) Argentina 8,144[2] 3.5[3] 4.8[4] 1.6[4] x (M)[5] x x The Bahamas 0[6] nk nk nk x x x x Bolivia nk nk nk nk x x x x Brazil nk 5 9.9 [7]6 nk nk x x x x Chile nk nk nk nk x x x x Colombia 14,893[8] 5.5[9] 31.6[9] nk [10,11] (M)[10,11] x x Costa Rica nk7 nk nk nk x x x x Dominican Republic <1,359[13]8 3.2[13]9 22.8[14]10 nk 2[15] x x x Ecuador nk nk nk nk x x x x El Salvador nk nk nk nk x x x x Guatemala nk nk nk nk x x x x Guyana nk nk nk nk x x x x Haiti nk nk nk nk x x x x Honduras nk nk nk nk x x x x Jamaica nk nk nk nk x x x x Mexico 164,157[18] 11 4.4[19] 12 96[20] 13 0.2[4] [17] (M)[21] [21] x14 Nicaragua nk nk nk nk x x x x Panama 5,714[22] nk nk nk x x x x Paraguay nk nk 9.8[23] nk x x x x Peru nk nk nk nk x x x x Puerto Rico 28,000[24] 11.3[25] 15 78.4 - 89[27,28] 16 nk [29] (M,B)[29] [29] x Suriname nk[30] 17 nk nk nk x x x x Uruguay nk nk nk nk x x x x Venezuela nk nk nk nk x x x x nk = not known 1 Countries with reported injecting drug use according to Larney et al in 2017. -

CARPHA State of Public Health Inaugural Report 2013

Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 ContentsExecutive Summary ............................................................................................................. ........................................................... 3 15 AbbreviationsFigures ....................................................................................................................... and Acronyms .......................................................................... 1120 ExecutiveTables ....................................................................................................................... Summary ........................................................................... 10 24 FiguresSection 1 Regional Health Overview ........................................................................................... ......................... 20 25 Tables1.1 Demographics .............................................................................................................. ............................................................. 23 27 Section 1.1.1 The1 Regional Caribbean Health Region Overview ................................................................................................... ............................................... 2527 1.1.1.1 Demographic overview of CARPHA Member States .............................................................................. -

Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean 2019

2019 Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean The new global financial context: effects and transmission mechanisms in the region Thank you for your interest in this ECLAC publication ECLAC Publications Please register if you would like to receive information on our editorial products and activities. When you register, you may specify your particular areas of interest and you will gain access to our products in other formats. www.cepal.org/en/publications ublicaciones www.cepal.org/apps 2019 Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean The new global financial context: effects and transmission mechanisms in the region 2 Executive summary Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Mario Cimoli Deputy Executive Secretary Raúl García-Buchaca Deputy Executive Secretary for Management and Programme Analysis Daniel Titelman Chief, Economic Development Division Ricardo Pérez Chief, Publications and Web Services Division The Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean is issued annually by the Economic Development Division of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). The 2019 edition was prepared under the leadership of Daniel Titelman, Chief of the Division, and coordinated by Ramón Pineda Salazar and Daniel Titelman. In the preparation of this edition, the Economic Development Division was assisted by the Statistics Division, the Division of International Trade and Integration, the ECLAC subregional headquarters in Mexico City and Port of Spain, and the Commission’s country offices in Bogotá, Brasilia, Buenos Aires, Montevideo and Washington, D.C. Part I, entitled, “The economic situation and outlook for 2019”, was prepared with input from the following experts: Alejandra Acevedo, Claudio Aravena, Pablo Carvallo, Claudia de Camino, Ivonne González, Michael Hanni, Juan Pablo Jiménez, Noel Pérez, Esteban Pérez Caldentey, Ramón Pineda Salazar, José Antonio Sánchez, Cecilia Vera and Jürgen Weller. -

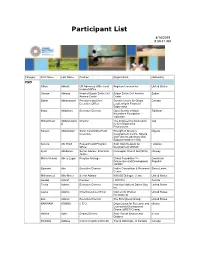

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

Antigua & Barbuda's 2015-2020 National Action Plan

Antigua & Barbuda’s 2015-2020 National Action Plan: Combatting Desertification, Land Degradation & Drought i | P a g e Table of Contents FOREWORD................................................................................................................................................. VI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................................................. VII ANTIGUA & BARBUDA’S 2015-2020 NATIONAL ACTION PLAN PROJECT TEAM.................................. VIII ACRONYMS.................................................................................................................................................IX EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................XI BACKGROUND...........................................................................................................................................12 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................................12 DESCRIPTION OF ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA..........................................................................................................13 Geography ........................................................................................................................................ 13 Climate.............................................................................................................................................. -

Lovell 0708 Antigua Barbuda

REGIONALISM VERSUS NATIONAL SOVEREIGNTY: THE PROMISE AND PROBLEMS OF A CARICOM FISHERIES AGREEMENT Tricia Lovell The United Nations-Nippon Foundation Fellowship Programme 2007 - 2008 DIVISION FOR OCEAN AFFAIRS AND THE LAW OF THE SEA OFFICE OF LEGAL AFFAIRS, THE UNITED NATIONS NEW YORK, 2008 DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Antigua & Barbuda, the United Nations, the Nippon Foundation of Japan, or the University of Massachusetts - Boston. © 2008 Tricia Lovell. All rights reserved. i ABSTRACT The Caribbean Sea is the second largest sea in the world and is characterised by its complex biogeography and diversity of marine life. Thirty-three States and territories border the region, including the fifteen members and five associate members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM). The CARICOM States have had a long and tumultuous history of economic integration, culminating with the formation of the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME) in 2006. In February 2003, the CARICOM Heads of Government accepted and endorsed a proposal by one of its member States to create a Common Fisheries Policy and Regime (CFPR) for the CARICOM region. This regime would essentially extend the rights and freedoms enjoyed under the CSME to the fisheries economic sectors of member States. In so doing, it would create a regional arrangement that would include the creation of a Common Fisheries Zone (CFZ), encompassing the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of member States beyond the 12-mile territorial sea. Within the CFZ, the Community members would be allowed equal access to surplus stocks deemed able to sustain harvest.