Using Date Specific Searches on Google Books to Disconfirm Prior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pursuit of Excellence Published for the Nursing Staff of Miami Children’S Hospital

PURSUIT OF EXCELLENCE PUBLISHED FOR THE NURSING STAFF OF MIAMI CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Volume 7 • Issue 1 • Spring 2006 Miracles in Haiti By Carolyn Domina, ARNP, MSN, CNOR, CNABC Operating Room se Lea ur de ince 2003, a N r surgical team S from MCH has made multiple trips to Haiti to help children diagnosed with hydrocephalus. With the help of Project Medis- hare, Helping Hands Clinic and from the In t Pavillon Notre Dame th igh des Pauvres, where the e Spotl surgeries are performed in Haiti, we have been Debbie Salani able to make a differ- surgeries as possible before dark. When night Director of ence in the lives of dozens of families. falls, we generally lose power and water. Emergency Services The neurosurgical team has been per- The children that we treat range in age forming a procedure known as a ventricular from a few months to 12 years of age, with peritoneal shunt, which involves placement some being a bit older. Most of these kids Debbie brings to her of a small flexible plastic tube that diverts role more than 25 years excess cerebral spinal fluid from the brain continued on page 6 experience as a pediatric to another part of the body where the fluid nurse practitioner. can be reabsorbed. We also have performed a procedure known as an endoscopic third In this issue ventriculostomy (ETV) in which a small hole Degrees: is made in the floor of the third ventricle of Implementing a Humpty Dumpty FallsTM • Bachelor’s degree in the brain which allows the cerebrospinal fluid Scale & Prevention Program psychology from to bypass the obstruction and flow toward the A Day in the Life of a Nurse Marywood University in area where it can be excreted by the body. -

Quilt Project Index

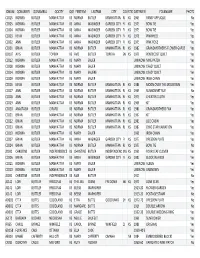

IDNUM QONAMEFI QONAMELA QOCITY QOSTATEFIRSTNM LASTNM CITY COUNTYSTATEDATEMEN FOLKNAME PHOTOS CC015 NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN KS NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN RL KS 1965 PANSY APPLIQUE No CC005 NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN KS ANNA WASINGER GARDEN CITY FI KS 1973 BOW TIE Yes CC004 NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN KS ANNA WASINGER GARDEN CITY FI KS 1973 BOW TIE Yes CC003 KEVIN BUTLER MANHATTAN KS ANNA WASINGER GARDEN CITY FI KS 1978 PINWHEEL Yes CC002 ANN BUTLER MANHATTAN KS ANNA WASINGER GARDEN CITY FI KS 1975 PINK ROSE Yes CC001 BRIAN BUTLER MANHATTAN KS NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN RL KS 1982 GRANDMOTHER'S FLOWER GARDE Yes DD107 AVIS BUTLER TOPEKA KS AVIS BUTLER TOPEKA SN KS 1979 PENTECOST QUILT Yes CC012 NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN KS MARY SAUER UNKNOW NINE PATCH Yes CC008 NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN KS MARY SAUER UNKNOW CRAZY QUILT Yes CC014 NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN KS MARY SAUERE UNKNOW CRAZY QUILT Yes CC009 NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN KS MARY SAUER UNKNOW IRISH CHAIN Yes CC016 KEVIN BUTLER MANHATTAN KS NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN RL KS 1986 MOON OVER THE MOUNTAIN Yes CC017 ANN BUTLER MANHATTAN KS NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN RL KS 1969 SUNBONNET SUE No CC018 ANN BUTLER MANHATTAN KS NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN RL KS 1975 CHEATER CLOTH Yes CC019 ANN BUTLER MANHATTAN KS NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN RL KS 1968 KIT Yes CC020 ANASTASIA BUTLER GIRARD KS NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN RL KS 1980 GRANDMOTHERS FAN Yes CC021 BRIAN BUTLER MANHATTAN KS NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN RL KS 1967 KIT Yes CC022 BRIAN BUTLER MANHATTAN KS NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN RL KS 1983 LOG CABIN Yes CC023 BRIAN BUTLER MANHATTAN KS NORMA BUTLER MANHATTAN -

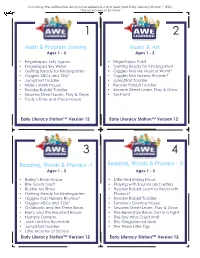

Math & Problem Solving Music & Art Reading, Words

Cut along the dotted line and place reference cards near your Early Literacy Station™ (ELS). *Title not included on ELS Tablet 1 2 Math & Problem Solving Music & Art Ages 1 - 3 Ages 1 - 3 • Fingertapps Jelly Jigsaw • Fingertapps Paint • Fingertapps Sky Writer • Getting Ready for Kindergarten • Getting Ready for Kindergarten • Giggles Kids My Musical World* • Giggles ABCs and 123s* • Giggles Kids Nursery Rhymes* • JumpStart Toddler • JumpStart Toddler • Millie’s Math House • Reader Rabbit Toddler • Reader Rabbit Toddler • Sesame Street Learn, Play & Grow • Sesame Street Learn, Play & Grow • Tux Paint • Trudy’s Time and Place House Early Literacy Station™ Version 12 Early Literacy Station™ Version 12 3 4 Reading, Words & Phonics -1 Reading, Words & Phonics - 2 Ages 1 - 3 Ages 1 - 3 • Bailey’s Book House • Little Red Riding Hood • Billy Goats Gruff • Playing with Sounds and Letters • Buckle My Shoe • Reader Rabbit Learn to Read with • Getting Ready for Kindergarten Phonics* • Giggles Kids Nursery Rhymes* • Reader Rabbit Toddler • Giggles ABCs and 123s* • Sammy’s Science House • Goldilocks and the Three Bears • Sesame Street Learn, Play & Grow • Harry and the Haunted House • The Berenstain Bears Get in a Fight • Humpty Dumpty • The Boy Who Cried Wolf • Jack and the Beanstalk • The Gingerbread Man • JumpStart Toddler • The Three Little Pigs • Little Monster at School Early Literacy Station™ Version 12 Early Literacy Station™ Version 12 Cut along the dotted line and place reference cards near your Early Literacy Station™ (ELS). *Title not included -

Department of Drama ® Presents

Paris Junior College Department of Drama ® presents Free Virtual Production on Zoom 7:30 p.m., Dec. 3, 4, 5 • 2:30 p.m., Dec. 6 Message from the Department of Drama Paris Junior College’s Department of Drama would like to ex- tend our warmest welcome to all in the 2020-21 theatre sea- son. Our Department has a tradition of exceptional students who have graced our stages, learned in our classrooms, and worked in our studios. As a student of theatre at PJC they are joining an accom- plished faculty of artists and scholars who are committed to creating, researching, and teaching exciting theatre and dra- ma. Our students develop skills both on and offstage while preparing to join the growing network of PJC Alumni in the professional and educational world of theatre arts. Whether students are a major, or just a curious student taking classes, we encourage them to become involved in the many activities of our department; this is an essential way to chal- lenge themselves and discover new insights as a part of their undergraduate education and experience. Students looking to venture into both music and drama have the option of a concentration in Musical Theatre here at Paris Junior College. On behalf of the students and faculty of the PJC Department of Drama we welcome you to our home. The Drama Faculty Alice in Cyberspace SCENES Scene 1: Alice’s Gaming Party Scene 2: The Kingdoms of the Red and White Queens Scene 3: Humpty Dumpty’s Wall Scene 4: The Lake of Tears with the Mock Turtle and Gryphon Scene 5: The Mad Tea Party Scene 5.5 / Scene -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Black Woman Black Man Spirit Tree

Cane River Chronicles I & II: A collection of poems/short stories birthed from the memories of my ancestors of Cane River (Natchitoches Parish) By Debra Roberson I. Black woman You are the creator of all life. In your womb is the foundation of a past that defines our future. From your being evolves all nations, kindred, and tongues. Black to Red to Yellow to White- we owe our existence to you. We behold your glory- innate, incomprehensible, intimate, you are beautiful beyond words. Knowledgeable beyond understanding. Your strength spans man’s weakness by creating a bridge from generation to generation. Without you we cease to be. For you, Black woman, are the essence of God given life itself. Black man You have toiled until your hands are calloused and bruised. You have had to stand by while your family was torn apart and your women raped. Even though from your loins flowed life, you were enslaved and told that you are less than human. You hung your head in shame as you passed a white person and you had to cross to the other side of the street. Your strong black back bore the pain and sorrow of your heritage and with every crack of that whip they tried to beat that pride out of you. You were born of kings and queens. You have forgotten that you are royalty. Where formal slavery hid in the shadows, you are still enslaved in the prisons of this “Great Country. “You matter” Don’t lose sight of your greatness. We need you, Black man. -

Colonial Theatre Humpty Dumpty Program

Week of April 3, 1905 COLONIAL THEATRE PROGRAM. WEEK OF APRIL 3, 1906. THE GEM OF THE WEST INDIES The Warm Welcome of the Golden Caribbean awaits you In JAMAICA With its temptiDg accessibility and the moderate cost of the trip, no other spot holds out such fair promise or a perfect winter holiday. Reached by a bracing sea trip of four dava oq vessels which afford the traveller every modern convenience and comfort. Th( UNITED FRUIT COMPANY’S Steel Twin-Screw U. S. Mail Steamships SAIL WEEKLY FROM BOSTON Round Trip $75—Including Meals and Stateroom—One Way $40 We have published a beautifully illustrated book, “ A Happy Month in Jamaica,” and issue a monthly paper, * The Golden Caribbean.” Both will be sent to those interested in Jamaica, by addressing— UNITED FRUIT COMPANY, LONG WHARF, BOSTON Raymond & Whitcomb Co. W. H. Kaves, City Passenger Agent Thos. Cook & Son 200 Washington Street Ohas. Y. Dasey, 8 Broad Street [Opposite Amei Building] Tel. 3497 Main Tel. 3956 Maia JUSTCOLONIAL THEATRETELEPHONEPROOKAM. WEhK OF A PHIL 3, 1905. Branch Exchange 555 Oxford connects all offices Branch Exchange 72 Newton connects all offices for “ suburban subscribers " FOR FOR ^ MEN WOMEN FANCY GOWNS WAISTCOATS REAL LACES COATS GLOVES TROUSERS FEATHERS SUITS COATS OVERCOATS WALKING NECKWEAR SUITS GLOVES &c RIBBONS &c FOR THE HOM E Furniture Covering's Rugs Blankets Carpets Portieres Draperies Dace and Muslin Curtains Embroideries Dinens Silks Satins Cottons &c Cleansed or Dyed and Refinished Properly LEWANDO’S FRENCH dyeing AND CLEANSING COMPANY 17 Temple Place BOSTON 284 Boylston Street 2206 Washington St Roxbury 1274 Massachusetts Ave Cambridge 9 Galen St Watertown (at Works) Newton Delivery Bundles called for and delivered in Boston and suburbs Also NEW YORK PHILADELPHIA WASHINGTON BALTIMORE PROVIDENCE NEWPORT HARTFORD NEW HAVEN LYNN COLONIAL THEATRE PROGRAM. -

Listing of Child Care Providers Reporting Closure Due to COVID-19 As of 4/3/2020 4:20 PM

Listing of Child Care Providers Reporting Closure Due to COVID-19 as of 4/3/2020 4:20 PM Closure Start Closure End Provider Number Provider Name Date Date Pre_K Address City ZipCode County CCLC-38436 1 Love Childcare & Learning Center 3/23/2020 4/8/2020 N 485 East Frontage Road Sylvania 30467 Screven CCLC-35618 1-2-3 Tots Learning Center 3/17/2020 NULL N 114 West 61st Street Savannah 31405 Chatham CCLC-28408 1st Creative Learning Academy 3/23/2020 4/3/2020 Y 5771 Lawrenceville Hwy Tucker 30084 Gwinnett CCLC-22766 1st Creative Learning Academy #2 3/17/2020 3/27/2020 Y 2527 Old Rockbridge Rd. Norcross 30071 Gwinnett CCLC-37311 1st Creative Learning Academy #3 3/23/2020 4/3/2020 Y 635 Exchange Place Lilburn 30047 Gwinnett CCLC-36694 1st Step Learning Academy L.L.C 3/25/2020 NULL N 3217 New MacLand Road Suite Powder120 & 130 Springs 30127 Cobb EX-45322 21st CCLC @ Harper Elementary School 3/17/2020 3/27/2020 NULL 520 Fletcher Street Thomasville 31792 Thomas EX-48362 21st CCLC @ Pelham Elementary School 3/17/2020 3/27/2020 NULL 534 Barrow Avenue SW Pelham 31779 Mitchell EX-44295 21st CCLC @ Scott Elementary 3/17/2020 3/27/2020 NULL 100 Hansell Street Thomasville 31792 Thomas CCLC-19930 5 Star Childcare & Learning Center 3/16/2020 4/6/2020 Y 4492 Lilburn Industrial Way SouthLilburn 30047 Gwinnett CCLC-33032 5-Star Childcare Center 3/20/2020 NULL N 1945 Godby Road College Park 30349 Clayton CCLC-48971 A Brighter Choice Learning Academy 3/16/2020 NULL N 140 Lowe Road Roberta 31078 Crawford CCLC-39661 A Brighter Day Early Learning Academy 3/23/2020 4/10/2020 N 6267 Memorial Drive, Suite LL Stone Mountain 30083 DeKalb CCLC-51382 A Brighter Day Early Learning Academy II 3/23/2020 4/10/2020 N 4764 Rockbridge Road Stone Mountain 30083 DeKalb CCLC-3318 A Child's Campus 3/19/2020 NULL N 2780 Flat Shoals Road Decatur 30034 DeKalb CCLC-14468 A Child's Dream Childcare and Learning Center 3/17/2020 NULL N 2502 Deans Bridge Road Augusta 30906 Richmond CCLC-937 A Child's World - Columbia Rd. -

Episode Guide

Last episode aired Monday May 21, 2012 Episodes 001–175 Episode Guide c www.fox.com c www.fox.com c 2012 www.tv.com c 2012 www.fox.com The summaries and recaps of all the House, MD episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on May 25, 2012 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.36 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 Paternity . .5 3 Occam’s Razor . .7 4 Maternity . .9 5 Damned If You Do . 11 6 The Socratic Method . 13 7 Fidelity . 15 8 Poison . 17 9 DNR ............................................... 19 10 Histories . 21 11 Detox . 23 12 Sports Medicine . 25 13 Cursed . 27 14 Control . 29 15 Mob Rules . 31 16 Heavy . 33 17 Role Model . 35 18 Babies & Bathwater . 37 19 Kids ............................................... 39 20 Love Hurts . 41 21 Three Stories . 43 22 Honeymoon . 47 Season 2 49 1 Acceptance . 51 2 Autopsy . 53 3 Humpty Dumpty . 55 4 TB or Not TB . 57 5 Daddy’s Boy . 59 6 Spin ............................................... 61 7 Hunting . 63 8 The Mistake . 65 9 Deception . 67 10 Failure to Communicate . 69 11 Need to Know . 71 12 Distractions . 73 13 Skin Deep . 75 14 Sex Kills . 77 15 Clueless . 79 16 Safe ............................................... 81 17 AllIn............................................... 83 18 Sleeping Dogs Lie . 85 19 House vs. God . 87 20 Euphoria (1) . 89 House, MD Episode Guide 21 Euphoria (2) . 91 22 Forever . -

Gender, Class, and Subjectivity in Mathematics: a Critique of Humpty Dumpty

Gender, Class, and Subjectivity in Mathematics: a Critique of Humpty Dumpty PAUL DOWLING There is a certain dualism which pervades discourse in the which are most commonly used in secondary schools in teaching of mathematics- indeed, which may be endemic England and Wales, the School Mathematics Project scheme in educational discourse generally- a dualism which op SMP 11-16, published by Cambridge University Press. I poses the curriculum, on the one hand, and the student, on shall consider the constitution of the subject in these and the other, and between which stands the teacher as broker some other texts firstly in relation to gender, and secondly in The student, in this conception, comes to the classroom with relation to social class certain individual needs and qualities and these are to be matched by m, in the worst of cases, frustrated by the Gender and mathematics texts curriculum This dualism is particulaily apparent in the In the original SMP "numbered" series, SMP Book I [5] newly established UK National Curriculum [DES, !988a; makes use of the following metaphors to introduce the 1988b; 1989] which clearly locates the facility for develop mathematical topic "rotation" ment within the individual, whilst placing in the mathe When your mother does the weekly wash, she probably uses matics curriculum the means of measuring it [Dowling, a wringer or spin dryer to remove most of the water from the 1990a] Ironically, this dualism is also apparent in a paper clothes, and your father probably uses a screw driver, a which carries -

Flower Arranging and Houseplant Division Rules Cheryl and Kristi Palsma (712-567-4452 [email protected])

Flower Arranging and Houseplant Division Rules Cheryl and Kristi Palsma (712-567-4452 [email protected]) Flower Arranging 1. Entries must be in place by 12:30 PM, Monday of the fair. 2. All fresh flowers used must be non-commercial; grown in your own garden or that of a friend or neighbor. Any fresh flowers purchased at a retail outlet will automatically disqualify that entry. Note--prepare as recommended in publication available from the Extension Office: “Preparing Cut Flowers and Houseplants for Exhibit.” 3. Mechanical aids such as wires are allowed, but should not be visible to the eye. 4. Fresh, silk, wood, feather, and/or pigskin flowers may be used. Dried weeds (excepting those noxious weeds that are prohibited – refer to General Rules) - may be used to create a flow of line in some arrangements. Plastic flowers and/or foliage are not acceptable. 5. Flower arranging will be conference judged with entries judged on basic flower arranging guidelines (see guidelines online at www.extension.iastate.edu/sioux/flowerarranging) and creativity. 6. No wall hangings will be accepted. 7. Outstanding Junior entries will be recognized with Junior Merit ribbons. 8. One Champion ribbon and one Reserve Champion ribbon will be given over-all with Intermediate and Seniors competing together. 9. A "Best of Show" plaque will be awarded. Flower arrangements and houseplants will compete for this honor. 10. All entries are released on Thursday at 7:00 PM. Flower Arranging Classes Class FA 1-- Any fresh flower and greenery arrangement made by the 4-H'er Class FA2 – Any arrangement using a bud vase and 1-3 fresh flowers with appropriate greens and accents. -

CALENDAR Meaningful Moments (Preschool-Aged)

CALENDAR Meaningful Moments (Preschool-aged) Slow-down Mealtime Talking Wiggle Think Follow-me Sensory Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Have your child help Using red, yellow, and Play A Game! Read a story Shape Hunt Explore the spice set the table, have blue paint, mix paint to Take turns hiding a together and then Cosmic Kids Yoga Find 2D/3D shapes create new colors; cabinet! Sort into 2 them “estimate” how small object and make up a different (YouTube) in your house and have your child show groups – smells they many will attend finding it ending identify them you how to recreate like/dislike dinner one of their colors. Penguin Race Try some new When going to a Speed Scribble Learn/memorize a Find an object to use Blow up balloons, foods—have your different part of the Be brave and show Find a fast song and Nursery Rhyme as a unit of measure put one between child pick three food house, challenge interest in how they have you child (Humpty Dumpty, (paperclip, shoe, your legs and keep it items, try them all, your child to walk are playing by draw/scribble fast, Baa Baa Black marker) and practice there while racing to and then pick a like a… (bear, crab, playing with them! repeat with slow Sheep) measuring the finish line favorite new food fly like a bird, etc.) music Freeze Dance! During play, expand Make Bubbles! Letter Hunt Cup Towers During a meal take Play a Game! Put on a song and ideas and narrate (6 C water, 1 C dish Search the As a family build cup turns asking “What’s “Simon Says” or when someone actions