Hawkins Catalogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artistic Movement Membership and the Career Profiles of Canadian Painters

DOCUMENT DE TRAVAIL / WORKING PAPER No. 2021-05 Artistic Movement Membership And The Career Profiles Of Canadian Painters Douglas J. Hodgson Juin 2021 Artistic Movement Membership And The Career Profiles Of Canadian Painters Douglas Hodgson, Université du Québec à Montréal Document de travail No. 2021-05 Juin 2021 Département des Sciences Économiques Université du Québec à Montréal Case postale 8888, Succ. Centre-Ville Montréal, (Québec), H3C 3P8, Canada Courriel : [email protected] Site web : http://economie.esg.uqam.ca Les documents de travail contiennent des travaux souvent préliminaires et/ou partiels. Ils sont publiés pour encourager et stimuler les discussions. Toute référence à ces documents devrait tenir compte de leur caractère provisoire. Les opinions exprimées dans les documents de travail sont celles de leurs auteurs et elles ne reflètent pas nécessairement celles du Département des sciences économiques ou de l'ESG. De courts extraits de texte peuvent être cités et reproduits sans permission explicite des auteurs à condition de faire référence au document de travail de manière appropriée. Artistic movement membership and the career profiles of Canadian painters Douglas J. Hodgson* Université du Québec à Montréal Sociologists, psychologists and economists have studied many aspects of the effects on human creativity, especially that of artists, of the social setting in which creative activity takes place. In the last hundred and fifty years or so, the field of advanced creation in visual art has been heavily characterized by the existence of artistic movements, small groupings of artists having aesthetic or programmatic similarities and using the group to further their collective programme, and, one would suppose, their individual careers and creative trajectories. -

Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism

Konstvetenskapliga institutionen Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Författare: Olga Grinchtein © Handledare: Karin Wahlberg Liljeström Påbyggnadskurs (C) i konstvetenskap Vårterminen 2021 ABSTRACT Institution/Ämne Uppsala universitet. Konstvetenskapliga institutionen, Konstvetenskap Författare Olga Grinchtein Titel och undertitel: Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Engelsk titel: Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Handledare Karin Wahlberg Liljeström Ventileringstermin: Höstterm. (år) Vårterm. (år) Sommartermin (år) 2021 The portrait of sculptor emerged in the sixteenth century, where the sitter’s occupation was indicated by his holding a statue. This thesis has focus on portraits of sculptors at the turn of 1900, which have indications of profession. 60 artworks created between 1872 and 1927 are analyzed. The goal of the thesis is to identify new facets that modernism introduced to the portraits of sculptors. The thesis covers the evolution of artistic convention in the depiction of sculptor. The comparison of portraits at the turn of 1900 with portraits of sculptors from previous epochs is included. The thesis is also a contribution to the bibliography of portraits of sculptors. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Karin Wahlberg Liljeström for her help and advice. I also thank Linda Hinners for providing information about Annie Bergman’s portrait of Gertrud Linnea Sprinchorn. I would like to thank my mother for supporting my interest in art history. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 1995

Van Gogh Museum Journal 1995 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 1995. Waanders, Zwolle 1995 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012199501_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 6 Director's Foreword The Van Gogh Museum shortly after its opening in 1973 For those of us who experienced the foundation of the Van Gogh Museum at first hand, it may come as a shock to discover that over 20 years have passed since Her Majesty Queen Juliana officially opened the Museum on 2 June 1973. For a younger generation, it is perhaps surprising to discover that the institution is in fact so young. Indeed, it is remarkable that in such a short period of time the Museum has been able to create its own specific niche in both the Dutch and international art worlds. This first issue of the Van Gogh Museum Journal marks the passage of the Rijksmuseum (National Museum) Vincent van Gogh to its new status as Stichting Van Gogh Museum (Foundation Van Gogh Museum). The publication is designed to both report on the Museum's activities and, more particularly, to be a motor and repository for the scholarship on the work of Van Gogh and aspects of the permanent collection in broader context. Besides articles on individual works or groups of objects from both the Van Gogh Museum's collection and the collection of the Museum Mesdag, the Journal will publish the acquisitions of the previous year. Scholars not only from the Museum but from all over the world are and will be invited to submit their contributions. -

![Sgr5a [DOWNLOAD] Into the Light: the Paintings of William Blair Bruce (1859 – 1906) Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2951/sgr5a-download-into-the-light-the-paintings-of-william-blair-bruce-1859-1906-online-2642951.webp)

Sgr5a [DOWNLOAD] Into the Light: the Paintings of William Blair Bruce (1859 – 1906) Online

Sgr5a [DOWNLOAD] Into the Light: The Paintings of William Blair Bruce (1859 – 1906) Online [Sgr5a.ebook] Into the Light: The Paintings of William Blair Bruce (1859 – 1906) Pdf Free Tobi Bruce *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3565847 in Books 2014-08-05Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 12.00 x 1.00 x 9.70l, .0 #File Name: 1907804528256 pages | File size: 25.Mb Tobi Bruce : Into the Light: The Paintings of William Blair Bruce (1859 – 1906) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Into the Light: The Paintings of William Blair Bruce (1859 – 1906): 0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy mikeyPerfect condition Into the Light is a major retrospective of the work of William Blair Bruce (1859–1906), Canada's first Impressionist artist. Born in Hamilton, Ontario, Bruce spent his early career in France, where he became one of the group of international artists who studied alongside Claude Monet at Giverny, later moving to Sweden, where he built his home and studio.With remarkable paintings, some on loan from the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, as well as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, seven scholarly essays, and a wealth of archival material including photographs and letters, this is a significant survey of this influential artist and his life. About the AuthorTobi Bruce is Senior Curator of Canadian Historical Art at the Art Gallery of Hamilton. With over twenty years experience working with public collections, Tobi has curated over fifty exhibitions, researched regional and Canadian women artists and written for exhibition catalogues. -

The Turn of a Great Century

cover:Layout 1 8/27/09 9:34 PM Page 1 Guarisco Gallery The Turn of a Great Century 19th and Early 20th Century Paintings, Sculptures & Watercolors 1 WHY 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURIES (The Optimal Period for Collecting) T he turn of the 19th century into the 20th has always proven to be one of the most interesting eras in art history. It is the century that witnessed the greatest expression of the Academic tradition and it is the era that launched modernism through the developments of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. * * * * * * * * * * * * Academic: Realism. It is best defined as an artist’s mastery of a variety of painting techniques, including the depiction of atmosphere and natural light, intended to produce a picture that mimicked reality. This style reached its height in the latter part of the 19th century. Major artists of this period include: William Bouguereau, Jean-Léon Gérome, Alexandre Cabanel, Briton Riviere, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Modern: Impressionism and Post-Impressionism; the commencement of modern painting. This period is the beginning of experimentation with form, color, brushwork, and subject matter leading to modern art. These artists experimented with depicting the effects of light and using expressive color and brushwork to portray both figures and landscapes. Founding members include: Claude Monet, Eugène Boudin, Camille Pissarro, Pierre Auguste Renoir, and Albert Guillaumin—and their contemporaries—Edmond Petitjean, Henri Lebasque, Henri Martin, and Georges d’Espagnat. These artitsts produced works which continue to be most favored for their market value and aesthetic merit. 2 (at The Ritz-Carlton) Welcome to Guarisco Gallery Guarisco Gallery is a leading international gallery founded in 1980 specializing in museum quality 19th - and early 20th - century paintings and sculpture. -

Den Mytomspunna Konstnärsbyn Grez-Sur-Loing Region Västernorrland Startar Upp Ett Samarbete Med Frankrike

Den mytomspunna konstnärsbyn Grez-sur-Loing Region Västernorrland startar upp ett samarbete med Frankrike Fram till den 18 augusti visas på Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde utställningen ”Grez-sur- Loing – Konst och relationer”. Grez-sur-Loing är en mytomspunnen fransk konstnärsby som vid 1800-talets senare del var platsen för ett betydande konstliv med framförallt skandinaviska och anglosaxiska konstnärer, författare och musiker. Till byn, som är belägen cirka 6 mil sydost om Paris, kan snart konstnärer från Västernorrland söka sig för ett utbyte med stöd av regionen. Grez, som byn kallas i dagligt tal, omges av åkermark, närd av floden Loing som flyter genom landskapet. Under dess blomstrande konstnärstid fanns i byn två pensionat, Hôtel Chevillon och Hôtel Laurent. Det var på dessa pensionat som svenskarna bodde. I dag drivs Hôtel Chevillon av en stiftelse som präglas av en traditionsrik och inspirerande miljö med möjlighet till konstnärligt arbete, tankeutbyte och social gemenskap. Gästerna är alla konstnärer, författare, tonsättare eller vetenskapsmän. Konstnärskolonier är platser där det kreativa arbetet förenas med socialt umgänge. Jämfört med andra kolonier fanns i Grez en hög representation av kvinnliga konstnärer och många fann sina livskamrater där. På den många gånger återgivna bron över floden Loing friade Carl Larsson till Karin Bergöö. 1884 föddes i Grez deras första barn, dottern Suzanne. Karin och Carl var dock inte de enda som fann kärleken i Grez. Karl Nordström träffade här konstnären Tekla Lindeström. I Grez bodde även paret Emma Löwstädt och Francis Brooks Chadwick. De bodde i Grez permanent under åren 1889–1894 då de flyttade in i den så kallade rosa paviljongen i Hôtel Chevillons trädgård. -

To Download the PDF File

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI* A New Matrix of the Arts: A History of the Professionalization of Canadian Women Artists, 1880-1914 Susan Butlin, M.A. School of Canadian Studies Carleton University, Ottawa A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 2008 © Susan Butlin, 2008 Library and Archives Biblioth&que et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de ('Edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your Tile Votre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-60128-0 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-60128-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lntemet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimis ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

On Theartof Being Canadian UBC Press Is Proud to Publish the Brenda and David Mclean Canadian Studies Series

On theartof Being Canadian UBC Press is proud to publish the Brenda and David McLean Canadian Studies Series. Each volume is written by a distinguished Canadianist appointed as a McLean Fellow at the University of British Columbia, and reflects on an issue or theme of profound import to the study of Canada. W.H. New, Borderlands: How We Talk about Canada Alain C. Cairns, Citizens Plus: Aboriginal Peoples and the Canadian State Cole Harris, Making Native Space: Colonialism, Resistance, and Reserves in British Columbia John F. Helliwell, Globalization and Well-Being Julie Cruikshank, Do Glaciers Listen? Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination on the of being artCanadian Sherrill Grace © UBC Press 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), www.accesscopyright.ca. 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Grace, Sherrill E. On the art of being Canadian / Sherrill Grace. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-7748-1578-9 1. National characteristics, Canadian, in art. 2. Nationalism and the arts — Canada. 3. Arts, Canadian — 20th century. 4. Arts, Canadian — 21st century. I. Title. FC95.5.G72 2009 700.971 C2009-904155-3 UBC Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for our publishing program of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP), and of the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council. -

Vivre À Grez N°62 Printemps 2019

N° 62 - PRINTEMPS 2019 VivreVivre àà www.grezsurloing.frGrezGrez Magazine d’informations de Grez-sur-Loing Seine-et-Marne - 1,50€ • Travaux de rénovation du réseau fuyard d’assai- LE MOT DU MAIRE nissement collectif (Rue Victor Hugo et du Vieux pont) • Fin des travaux de construction du bassin L’année 2018 a été bien chargée d’orage en raison de chantiers impor- • Espace Victor Hugo (climatisation cantine et tants parmi lesquels : salle de réunion + amélioration de l’acoustique de • La construction en cours des la salle de réunion) nouveaux vestiaires • Déploiement de l’informatique (écrans interac- • L’extension du réseau d’as- tifs) dans quatre salles de classe du Groupe Sco- sainissement collectif pour les laire + équipement en tablettes WC des prés du Vieux Pont et des vestiaires spor- • Travaux d’accessibilité tifs • Travaux de voirie. • Le démarrage de la construction d’un bassin Et pour terminer, en complément à l’organisation d’orage et suivi de ces travaux, la municipalité travaille • La réhabilitation des bureaux de la Mairie sur deux dossiers importants que sont : • La réfection des peintures de la salle Fernande • La procédure de renouvellement de la Déléga- Sadler tion de Service Public pour la gestion du Camping • Le remplacement de tous les volets roulants du des Prés groupe scolaire • La réfection de la cour de récréation pour • La procédure de renouvellement de la Déléga- classes maternelles tion de Service Public pour la gestion du Service • L’installation de stores de protection solaire d’Assainissement « Collectif et Non-collectif » (AC dans la salle informatique du groupe scolaire et ANC). -

ÉTABLISSEMENT PUBLIC Des Musees D'orsay Et De L'orangerie

ÉTABLISSEMENT PUBLIC Des MUSEEs D'ORSay et de l'orangerie Service de la conservation du musée d'Orsay Émeline Levasseur, stagiaire archiviste, sous la direction de la mission des archives du ministère de la Culture et de la Communication Première édition électronique Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 2016 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_055473 Cet instrument de recherche a été rédigé avec un logiciel de traitement de texte. Ce document est écrit en ilestenfrançais.. Conforme à la norme ISAD(G) et aux règles d'application de la DTD EAD (version 2002) aux Archives nationales, il a reçu le visa du Service interministériel des Archives de France le ..... 2 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 20160327/1-20160327/103 Niveau de description fonds Intitulé Service de la conservation du musée d'Orsay Date(s) extrême(s) 1987-2006 Nom du producteur • Musée d'Orsay (1978-1987) • Établissement public du musée d'Orsay (2004-2009) • Établissement public du musée d'Orsay et du musée de l'Orangerie depuis 2010 Importance matérielle et support 47 cartons de type DIMAB soit 15,66 m.l. Localisation physique Pierrefitte-sur-Seine Conditions d'accès Les documents sont librement communicables à l'exception des articles 1 à 44 portant des informations d'ordre privée qui sont communicables au terme d'un délai de 50 ans à compter de la date du document le plus récent (article L213-2 du Code du Patrimoine). Conditions d'utilisation Selon le règlement de la salle de lecture. DESCRIPTION Présentation du contenu Ce répertoire numérique décrit les archives versées par le service de la conservation de l'Établissement public des musées d'Orsay et de l'Orangerie, qui, depuis la création du musée, « assure l'inventaire des collections, la conservation, l'étude scientifique, et la présentation des œuvres, ainsi que les publications s'y rapportant » (article 3 de l'arrêté du 14 mars 1986 portant organisation du musée d'Orsay). -

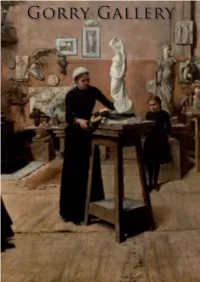

Gorry Gallery 16

Gorry Gallery 16. William H. Bartlett (Detail) FRONT COVER: William H. Bartlett 1858-1932 Catalogue Number 16. (Detail) © GORRY GALLERY LTD. GORRY GALLERY requests the pleasure of your company at the private view of An Exhibition of 18th - 21st Century Paintings on Wednesday, 14th March, 2007 Wine 6 o’clock This exhibition can be viewed prior to the opening by appointment and at www.gorrygallery.ie Kindly note that all paintings in this exhibition are for sale from 6.00 p.m. 14th March – 31st March 2007 16. WILLIAM HENRY BARTLETT, 1858-1932 ‘His Last Work’ Oil on canvas 115.5 x 153.5 Signed and dated 1885 Exhibited, Royal Academy, 1885 (no 1160) Provenance: William Wallace Spence, Baltimore City Gifted to the Presbyterian House, Towson, Maryland by Mrs Bartow Van Ness and Mrs Frederick Barron granddaughters of William Wallace Spence Bears label of Dicksee and Dicksee, 1 Pall Mall Place, London and a label inscribed with the title in the artist’s hand, giving his address as Park Lodge, Church Street, Chelsea In its original carved and gilded exhibition frame, possibly designed by the artist William Henry Bartlett is emerging as one of the most interesting and accomplished artists to have worked in Ireland in the nineteenth century. Although a visitor, he engaged directly with Irish subject matter both in paint and in print. He is known today for his remarkably innovative views of daily life in the West, which form an important link between the essentially Victorian, and often sentimental, work of other visiting artists such as Howard Helmick and the figurative work of Charles Lamb and Paul Henry in the early decades of the twentieth century. -

2014 Annual Report

2014 ANNUAL REPORT William Blair Bruce (Canadian 1859-1906) Summer Day (detail) c. 1890 oil on canvas Art Gallery of Hamilton, Bruce Memorial, 1914 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Art Gallery of Hamilton Board of Directors 3 Message from the Chair and Director 4 Exhibition and Program Highlights 6 AGH Volunteer Committee – Chair’s Report, June 2015 10 Donor Support and Sponsorship (as of May 15, 2015) 15 2014 Exhibitions 18 2014 Acquisitions 20 2014 Programming 22 123 King Street West, Hamilton, Ontario L8P 4S8 T: 905.527.6610 F: 905.577.6940 E: [email protected] www.artgalleryofhamilton.com Charitable registration number: 10672 3588 RR0002 2 AGH BOARD OF DIRECTORS AS OF JUNE 1, 2015 Charles P. Criminisi, Chair Lou Celli, First Vice-Chair David Kissick, Secretary-Treasurer Filomena Frisina, Past Chair Dan Banko Paul Berton Dr. Brenda Copps Laurie Davidson Adrian Duyzer John Heersink Marilyn Hollick, Past Chair, AGH Volunteer Committee Craig Laviolette Tim McCabe Councillor Maria Pearson Councillor Arlene VanderBeek Anna Ventresca Dr. Leonard Waverman Shelley Falconer, President and CEO, ex officio 3 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR AND DIRECTOR 2014 was a monumental year for the Art Gallery of Hamilton. The AGH proudly celebrated its centennial with a year of extraordinary exhibitions, lectures, tours, programming and special events. The Gallery also entered a new chapter with the appointment of Shelley Falconer as President and CEO, following the retirement of Louise Dompierre who stepped down in November after 16 years of service. In October, the AGH announced the restitution of the painting Portrait of a Lady by the Dutch 17th-century artist Johannes Verspronk to those whom the AGH believes, after extensive research, to be the rightful owners.