Ottman, John (B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eddie Awards Issue

THE MAGAZINE FOR FILM & TELEVISION EDITORS, ASSISTANTS & POST- PRODUCTION PROFESSIONALS THE EDDIE AWARDS ISSUE IN THIS ISSUE Golden Eddie Honoree GUILLERMO DEL TORO Career Achievement Honorees JERROLD L. LUDWIG, ACE and CRAIG MCKAY, ACE PLUS ALL THE WINNERS... FEATURING DUMBO HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON: THE HIDDEN WORLD AND MUCH MORE! US $8.95 / Canada $8.95 QTR 1 / 2019 / VOL 69 Veteran editor Lisa Zeno Churgin switched to Adobe Premiere Pro CC to cut Why this pro chose to switch e Old Man & the Gun. See how Adobe tools were crucial to her work ow and to Premiere Pro. how integration with other Adobe apps like A er E ects CC helped post-production go o without a hitch. adobe.com/go/stories © 2019 Adobe. All rights reserved. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Premiere, and A er E ects are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe in the United States and/or other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Veteran editor Lisa Zeno Churgin switched to Adobe Premiere Pro CC to cut Why this pro chose to switch e Old Man & the Gun. See how Adobe tools were crucial to her work ow and to Premiere Pro. how integration with other Adobe apps like A er E ects CC helped post-production go o without a hitch. adobe.com/go/stories © 2019 Adobe. All rights reserved. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Premiere, and A er E ects are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe in the United States and/or other countries. -

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

THE MAGAZINE FOR FILM & TELEVISION EDITORS, ASSISTANTS & POST- PRODUCTION PROFESSIONALS THE SUMMER MOVIE ISSUE IN THIS ISSUE Once Upon a Time in Hollywood PLUS John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum Rocketman Toy Story 4 AND MUCH MORE! US $8.95 / Canada $8.95 QTR 2 / 2019 / VOL 69 FOR YOUR EMMY ® CONSIDERATION OUTSTANDING SINGLE-CAMERA PICTURE EDITING FOR A DRAMA SERIES - STEVE SINGLETON FYC.NETFLIX.COM CINEMA EDITOR MAGAZINE COVER 2 ISSUE: SUMMER BLOCKBUSTERS EMMY NOMINATION ISSUE NETFLIX: BODYGUARD PUB DATE: 06/03/19 TRIM: 8.5” X 11” BLEED: 8.75” X 11.25” PETITION FOR EDITORS RECOGNITION he American Cinema Editors Board of Directors • Sundance Film Festival T has been actively pursuing film festivals and • Shanghai International Film Festival, China awards presentations, domestic and international, • San Sebastian Film Festival, Spain that do not currently recognize the category of Film • Byron Bay International Film Festival, Australia Editing. The Motion Picture Editors Guild has joined • New York Film Critics Circle with ACE in an unprecedented alliance to reach out • New York Film Critics Online to editors and industry people around the world. • National Society of Film Critics The organizations listed on the petition already We would like to thank the organizations that have recognize cinematography and/or production design recently added the Film Editing category to their Annual Awards: in their annual awards presentations. Given the essential role film editors play in the creative process • Durban International Film Festival, South Africa of making a film, acknowledging them is long • New Orleans Film Festival overdue. We would like to send that message in • Tribeca Film Festival solidarity. -

Singer, Bryan (B

Singer, Bryan (b. 1965) by Richard G. Mann Bryan Singer in 2006. Photograph created by Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Flickr member [177]. Entry Copyright © 2008 glbtq, Inc. Image appears under the Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 license. Bryan Singer is a leading contemporary American director and producer of motion pictures and television programs. Working within such popular genres as film noir and science fiction, he challenges viewer expectations by overturning standard narrative formulae and by developing exceptionally complex characters. In his films, he consistently emphasizes the fluidity and ambiguity of all identity categories, including those pertaining to gender and sexuality. A gay Jewish man, he is acutely aware of the difficulties encountered by minorities. Therefore, many of his projects have been concerned with individuals and groups who have been stigmatized because of perceived differences from those who assume the authority to define what is normal. His X-Men (2000) and X-2 (2003) have achieved mainstream commercial success while simultaneously enjoying cult status among queer audiences. Origins: Childhood and Adolescence Bryan Singer was born on September 17, 1965 in New York City. At the age of two months, he was adopted by Norbert Singer, a corporate credit manager for Maidenform Company (a manufacturer of women's apparel), and Gloria Sinden, later a prominent environmental activist. He grew up in suburban New Jersey, primarily in the affluent communities of Princeton Junction and Lawrenceville. Although troubled by the divorce of his parents when he was twelve years old, he remained close to both of them. -

H[Appy Da}C;'^ Ws Minatic On

Who’s going !H[appy / t o lthe l next round i n pprep baseball? MotherV SEE.SPORTS. C l Da}C;'^ I a w s . M3g'cValley.ar .c o m -----------------— Mini-Cassia Good tvloriiiiig y Local studenin ts aim B usine!isseswaiy ^ Ira i wonian bilies5 High: 75’5 B ^■<4 ji. iB R illlP to invent nevew to o ls 1 ^ 1 of posis tag e hike across Europele SEE MlMl CASSIA. D707 Nlco and watm. Details: C8 SEE MAGICGic VALLEY, C l SEE MONEY. C l Crimsor A nnother’ss deterrminaticon £ I I n th e la te ttirit‘JfiOs, le am ietie keep linlin y fin g ers away, ’i'liis year, ihe ■News asked silver, 1 bad no running "Iwoiivoultl gel np at ibreein the reaiiers to bring iislhesii.•sioriesof ' Vanden Uosch h; ,-e exceptional MagicValleyley m o th ers, g waier or indoorDriiliimhinginher j morniii|lin g to d o th e w ash so I'll have 1 ler'sDay.we & I MiiiDesota honuline. To dn th e Iaundr>’. it all (lonedm before die children In celebriilion of Motlier' ^ for h e r rapidlyr grgrow ing family, sh e woke." sas id V anden Hosch, 7'), from111 are fealuringVancleii liosiosch. who I last year lost Wif'V white h a n d -c ra n k ed1 cliclothing througli a berjeroieronie hom e eadier ibis raised 12 chiliireii and la^ > a leg as a resuli ofalife-ilu-ll.r.'Mci.ir.e _______ wnngi;r..iin.«ctivliviivsodaniu'rous month.'111: "ll WIS veryciialleiigiiigio iden Boich gels a hug from h e rso n ._ T she took e.’?cepii([Itional measures to do that.'la l."’ cafaccideiitl Dare, while hertiier husband, Manrin, looks on during a event. -

Walter Murch's the Rule Of

Walter Murch’s The Rule of Six What is the perfect cut from one shot to another? Anna Standertskjöld Degree Thesis Film and Media 2020 EXAMENSARBETE Arcada Utbildningsprogram: Film och media Identifikationsnummer: Författare: Anna Standertskjöld Arbetets namn: Walter Murch’s The Rule of Six - What is the perfect cut from one shot to another? Handledare (Arcada): Kauko Lindfors Uppdragsgivare: Syftet med detta arbete var att undersöka vilka komponenter som utgör det perfekta klippet från en bild till en annan. Studien baserade sig på en uppsättning av regler som gjorts upp av den amerikanska ljudplaneraren och editeraren Walter Murch, som han utmyntat i sin bok In the Blink of an Eye: A Perspective on Film Editing. Denna regel kallar Murch för The Rule of Six. Studien baserade sig även på en litteraturanalys på existerande material om editering samt en tillämpning av vissa av regelns punkter på en scen ur filmen Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) om rockgruppen Queen – scenen, där bandet träffar sin framtida manager. Denna scen är nu mera känd för att vara ett exempel på dåligt editerande, vilket också var orsaken att jag ville undersöka exakt vad som gör den så dåligt editerad. Murchs sex regler består av känsla, berättelse, rytm, eye trace, tvådimensionellt skärmplan, och tredimensionellt handlingsutrymme, som alla är av olika värde vad gäller klippet. Resultaten visade att det som utgör ett perfekt klipp från en bild till en annan är då ett klipp förmedlar den rätta känslan i stunden av scenen, framåtskrider berättelsen på ett meningsfullt sätt, byggs upp i en intressant och rätt rytm, respekterar blickspårning och tvådimensionellt skärmplan, samt tredimensionellt handlingsutrymme. -

John Barry Aaron Copland Mark Snow, John Ottman & Harry Gregson

Volume 10, Number 3 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television HOLY CATS! pg. 24 The Circle Is Complete John Williams wraps up the saga that started it all John Barry Psyched out in the 1970s Aaron Copland Betrayed by Hollywood? Mark Snow, John Ottman & Harry Gregson-Williams Discuss their latest projects Are80% You1.5 BWR P Da Nerd? Take FSM’s fi rst soundtrack quiz! �� � ����� ����� � $7.95 U.S. • $8.95 Canada ������������������������������������������� May/June 2005 ����������������������������������������� contents �������������� �������� ������� ��������� ������������� ����������� ������� �������������� ��������������� ���������� ���������� �������� ��������� ����������������� ��������� ����������������� ���������������������� ������������������������������ �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������� ������������������������������������������������������ ����������������������������������������������������������������������� FILM SCORE MAGAZINE 3 MAY/JUNE 2005 contents May/June 2005 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 4 Editorial 31 The Circle Is Complete Much Ado About Summer. Nearly 30 years after -

Digital Cinema and the Legacy of George Lucas

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Digital cinema and the legacy of George Lucas Willis, Daniel Award date: 2021 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials. We exercise best efforts on our behalf and, in such instances, encourage the individual to consult the physical thesis for further information. -

Awards & Honours

oliveboard Free e-book LIST OF IMPORTANT AWARDS AND HONOURS (JANUARY - FEBRUARY 2019) For Bank and Government Exams Awards & Honours (January-February 2019) Free Current Affairs e-book Current affairs are an important part of General Awareness section in Banking and Government Exams. Therefore, we at Oliveboard regularly provide you with free current affairs e-books to aid you in your preparation. In this section questions related to Major Award Winners are frequently asked. Hence it becomes very important for all the candidates to be aware of all the Awards And Honours. In this ebook we bring to you the Major Awards conferred in the month of Jan-Feb 2019. Sample Questions Q.1 In the Golden Globe Awards 2019, which film has won the Best Motion Picture – Drama? 1. BlacKkKlansman 2. If Beale Street Could Talk 3. Black Panther 4. Bohemian Rhapsody 5. Star Is Born, A (2018) Answer – (4) Q.2 Which state does the Padma Vibhushan Teejan Bai belongs to? 1. Maharashtra 2. Madhya Pradesh 3. Chhattisgarh 4. Uttar Pradesh 5. Gujarat Answer – (3) In all the Bank and Government exams, every mark counts and even 1 mark can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, to help you get these important marks we have created a Free E-book on Major Awards and Honours Jan-Feb 2019. Awards & Honours (January-February 2019) Free Current Affairs e-book The Golden Globes Awards 2019 • 76th Annual Golden Globes Awards was held on 6th January 2019 in Beverly Hills, California. The Golden Globes Awards 2019 The list of Winners – Films Category Winner -

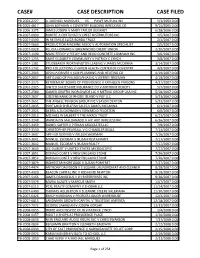

Case# Case Description Case Filed

CASE# CASE DESCRIPTION CASE FILED PB-2003-2227 A. MICHAEL MARQUES VS PAWT MUTUAL INS 5/1/2003 0:00 PB-2005-4817 JOHN BOYAJIAN V COVENTRY BUILDING WRECKING CO 9/15/2005 0:00 PB-2006-3375 JAMES JOSEPH V MARY TAYLOR DEVANEY 6/28/2006 0:00 PB-2007-0090 ROBERT A FORTUNATI V CREST DISTRIBUTORS INC 1/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0590 IN RE EMILIE LUIZA BORDA TRUST 2/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0663 PRODUCTION MACHINE ASSOC V AUTOMATION SPECIALIST 2/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0928 FELICIA HOWARD V GREENWOOD CREDIT UNION 2/20/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1190 MARC FEELEY V FEELEY AND REGO CONCRETE COMPANY INC 3/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1255 SAINT ELIZABETH COMMUNITY V PATRICK C LYNCH 3/8/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1381 STUDEBAKER WORTHINGTON LEASING V JAMES MCCANNA 3/14/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1742 PRO COLLECTIONS V HAVEN HEALTH CENTER OF COVENTRY 4/9/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2043 JOSHUA DRIVER V KLM PLUMBING AND HEATING CO 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2057 ART GUILD OF PHILADELPHIA INC V JEFFREY FREEMAN 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2175 RETIREMENT BOARD OF PROVIDENCE V KATHLEEN PARSONS 4/27/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2325 UNITED STATES FIRE INSURANCE CO V ANTHONY ROSCITI 5/7/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2580 GAMER GRAFFIX WORLDWIDE LLC V METINO GROUP USA INC 5/18/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2637 CITIZENS BANK OF RHODE ISLAND V PGF LLC 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2651 THE ANGELL PENSION GROUP INC V JASON DENTON 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2835 PORTLAND SHELLFISH SALES V JAMES MCCANNA 6/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2925 DEBRA A ZUCKERMAN V EDWARD D FELDSTEIN 6/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3015 MICHAEL W JALBERT V THE MKRCK TRUST 6/13/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3248 WANDALYN MALDANADO -

Marzo 2013 1949, Ritrae Il Pugile Professionista Walter Minciò Ad Invadere Le Sale Americane Sotto L’In - Mografia Kubrickiana

Il paradosso di Ozu di Marco Dalla Gassa Pochi registi hanno generato vocazioni come estrema raffinatezza ed eleganza, propria del - cibilmente “altro”, non contaminato dalle Ozu Yasujirō. Wenders, Hou Hsiao-hsien, l’ ikebana , l’arte della disposizione dei fiori recisi brutture del presente, come lo è chi trova ripa - Claire Denis, Kaurismäki, Kiarostami, Stanley (e per estensione degli oggetti nello spazio). Al - ro all’interno di un microcosmo (famigliare, Kwan, Kitano, Lindsay Anderson, Paul Schra - tre similitudini, si possono trovare con i compo - giovanile, impiegatizio) quasi potesse bastare a der, Kore-eda Hirokazu, Pedro Costa (e chissà nimenti haiku rispetto alla conduzione appa - se stesso, ieratico e incorruttibile. Egli è in - quanti altri) hanno speso parole di ammirazio - rentemente monocorde ed ellittica delle narra - somma rassicurante perché si presenta come ne nei suoi confronti e talvolta hanno cercato zioni, o con il cha no yu , la cerimonia del tè, di “il regista giapponese che assomiglia di più al - di “rubare” i segreti del suo mestiere. A questi cui condivide il gusto e la precisione per le esat - l’idea (comune) di regista della tradizione vanno aggiunti grandi studiosi di lingua ingle - te posture e le ritualità dei gesti. giapponese”. se (e non solo) come David Bordwell, Donald Il paradosso appena descritto – promotore di Eppure, a ben vedere, rassicurante – Ozu – non Richie, Edward Branigan, Noël Burch, Joan vocazioni ma ritenuto altresì “incomprensibi - lo è per nulla. La precisione con cui traccia le di - Mellen, Kristin Thompson, Jonathan Rosen - le” dalle stesse persone che hanno sentito la sua namiche di potere in Sono nato, ma… o nel baum, Max Tessier che hanno consacrato saggi, “chiamata” – rappresenta a nostro parere il se - quasi remake Buongiorno , sono quelle, ad esem - volumi e monografie al suo lavoro, taluni arri - greto del suo successo. -

100% Alfred Film/TV Titles

100% Alfred Film/TV Titles Rocky (1976 Film) – Bill Conti (Excluding Europe) Rocky’s Reward Gonna Fly Now Going the Distance Final Bell Fanfare for Rocky Alone in the Ring Rocky 2 (1979 Film) – Bill Conti (Excluding Europe) Redemption Overture Conquest Rocky 3 (1982 Film) – Bill Conti (Excluding Europe) Mickey Adrian Rocky 4 (1985 Film) – Vince DiCola (Excluding Europe) Living in America ( Dan Hartman & Charlie Midnight) Fanfare for Rocky Training Montage Hearts on Fire (Vincent DiCola, Joe Esposito & Edwin Fruge) Hairspray (2007 Film) – Marc Shaiman & Scott Wittman Come so far (Got so far to go) Ladies Choice The New Girl in Town The Golden Compass (2007 Film) – Alexandre Desplat Battle with the Tartars Epilogue Ice Bear Combat Iorek’s Victory Lee Scoresby’s Airship Adventure Lord Asriel Mother Riding Iorek Samoyed Attack Sky Ferry The Golden Compass The Wizard of Oz (1939 Film) – Herbert Stothart, Harold Arlen & E. Y. Harburg (Excluding Europe) Over the Rainbow If I Only Had a Brain We’re Off to See the Wizard If I Only Had a Heart Follow the Yellowbrick Road Cyclone If I Only Had the Nerve The Merry Old Land of Oz If I Were King of the Forest The Jitterbug Ding! Dong! The Witch is Dead! The Lullaby League The Lollipop Guild Come Out, Come Out 1 (You’re Out of the Woods) Optimistic Voices As Coroner I Must Aver March of the Winkies Munchkinland The Wizard of Oz Twister Happy Feet (2006 Animated Film) – John Powell Adelieland Fun Food Storm The Story of Mumble Happy Feet Happy Feet 2 (2011 Animated Film) – John Powell In the Hole Ramon and the Krill Lovelace Preshow Searching for the Kids The Doomberg Lands I Don’t Back Up.. -

UH West O'ahu to Host Creative Media Masters Series

NEWS RELEASE Contacts: Julie Funasaki Yuen, (808) 689-2604 Oct. 13, 2014 [email protected] Public Information Officer UH West O‘ahu to host Creative Media Masters Series presented by the Academy for Creative Media System Hollywood comes to UHWO with legendary filmmaker and film composer KAPOLEI --- This November, together with the University of Hawaiʻi Academy for Creative Media System, the University of Hawaiʻi – West O‘ahu will host a Creative Media Masters Series featuring presentations by an Academy Award-winning Hollywood filmmaker and a renowned Hollywood film composer and editor. The Creative Media Masters Series is part of UH West Oʻahu’s new Creative Media concentration and aims to increase student understanding of the art and business of content creation. All presentations are free and open to all students, faculty and the public. The Creative Media Masters Series presentations at UH West Oʻahu are made possible by the generous support of EuroCinema Hawaiʻi (ECH), the "festival within a festival" at the Hawaiʻi International Film Festival. ECH's mission is to promote cultural exchanges between the people of Hawaiʻi and Europe through film while supporting local student filmmakers and content creators. Film Composer John Ottman, Wednesday, Nov. 5 UH West Oʻahu Library ‘Uluʻulu Exhibition Space, First Floor 11 a.m. - 12:30 p.m. John Ottman holds dual distinctions as a leading film composer and an award winning film editor. He has edited and written the scores for a broad range of films, including The Usual Suspects, X- Men, X-Men 2, Superman Returns, Valkyrie, Jack the Giant Killer and Xmen: Days of Future Past.