Case Study Utrecht Rijnenburg, the Netherlands: Failure to Launch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utrecht CRFS Boundaries Options

City Region Food System Toolkit Assessing and planning sustainable city region food systems CITY REGION FOOD SYSTEM TOOLKIT TOOL/EXAMPLE Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and RUAF Foundation and Wilfrid Laurier University, Centre for Sustainable Food Systems May 2018 City Region Food System Toolkit Assessing and planning sustainable city region food systems Tool/Example: Utrecht CRFS Boundaries Options Author(s): Henk Renting, RUAF Foundation Project: RUAF CityFoodTools project Introduction to the joint programme This tool is part of the City Region Food Systems (CRFS) toolkit to assess and plan sustainable city region food systems. The toolkit has been developed by FAO, RUAF Foundation and Wilfrid Laurier University with the financial support of the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and the Daniel and Nina Carasso Foundation. Link to programme website and toolbox http://www.fao.org/in-action/food-for-cities-programme/overview/what-we-do/en/ http://www.fao.org/in-action/food-for-cities-programme/toolkit/introduction/en/ http://www.ruaf.org/projects/developing-tools-mapping-and-assessing-sustainable-city- region-food-systems-cityfoodtools Tool summary: Brief description This tool compares the various options and considerations that define the boundaries for the City Region Food System of Utrecht. Expected outcome Definition of the CRFS boundaries for a specific city region Expected Output Comparison of different CRFS boundary options Scale of application City region Expertise required for Understanding of the local context, existing data availability and administrative application boundaries and mandates Examples of Utrecht (The Netherlands) application Year of development 2016 References - Tool description: This document compares the various options and considerations that define the boundaries for the Utrecht City Region. -

Provincie Utrecht / Gemeente Woerden BRAVO-Projecten 3, 4, 6

Provincie Utrecht / gemeente Woerden BRAVO-projecten 3, 4, 6 en 8 Milieueffectrapport hoofdrapport Gemeente Woerden Woerden H Linschoten G t M Witteveen+Bos van Twickelostraat 2 postbus 233 7400 AE Deventer telefoon 0570 69 79 11 telefax 0570 69 73 44 INHOUDSOPGAVE blz. DEEL A: KERNINFORMATIE 1 1. INLEIDING 2 1.1. Voorgeschiedenis van het BRAVO-project 2 1.2. Waarover gaat het in dit MER? 3 1.3. Leeswijzer 4 1.4. De m.e.r.-procedure en de uiteindelijke afweging 5 1.4.1. De m.e.r.-procedure 5 1.4.2. De uiteindelijke afweging 7 1.5. Verband met andere procedures 7 2. PROBLEEMANALYSE EN DOEL 8 2.1. Ontstaan A12 BRAVO samenwerking 8 2.2. Probleemanalyse 9 2.2.1. Huidige ontsluitingsproblematiek Woerden en Harmelen 9 2.2.2. Huidige fileproblematiek Woerden 11 2.2.3. Huidig sluipverkeer in Woerden en Harmelen 12 2.2.4. Toekomstige situatie zonder de BRAVO-projecten 14 2.3. Doel van het voornemen 16 3. PROJECTEN EN PROJECTCOMBINATIES 17 3.1. De projecten 17 3.2. Toelichting op de projecten 17 3.2.1. BRAVO-project 3: Zuidelijke randweg Woerden 17 3.2.2. BRAVO project 4: Westelijke randweg Woerden 18 3.2.3. BRAVO project 6a: Zuidelijke randweg Harmelen 19 3.2.4. BRAVO project 6b: Westelijke randweg Harmelen 20 3.2.5. BRAVO project 6c: Oostelijke randweg Woerden 20 3.2.6. BRAVO project 8: Oostelijke randweg Harmelen 22 3.3. Projectcombinaties 23 3.4. Toelichting op de projectcombinaties 23 3.4.1. Variant A (2015): Autonome situatie + project 8 23 3.4.2. -

Geboorteregisters (1811-1912)

GEBOORTEREGISTERS (1811-1912) Abcoude-Baambrugge 1811-1912 Abcoude-Proostdij 1811-1912 Achthoven 1818-1857 Achttienhoven 1811, 1818-1912 Amerongen 1811-1912 Amersfoort 1811-1912 Asschat 1811 Baarn 1811-1912 Barwoutswaarder 1818-1912 Benschop 1811-1912 Breukelen-Nijenrode 1811-1912 Breukelen-St. Pieters 1818-1912 Breukeleveen 1811 Bunnik 1811-1912 Bunschoten 1811-1912 Cothen 1811-1912 Darthuizen 1811-1857 De Bilt 1811-1902 De Vuursche 1811, 1818-1912 Doorn 1811-1912 Driebergen 1811-1912 Duist 1811, 1818-1857 Eemnes 1811-1912 Everdingen 1812-1912 Gerverskop 1818-1857 Gravesloot, 's- 1811, 1818-1857 Grote en Kleine Koppel en 1811 Maarschalkerweerd Haarzuilens 1811, 1818-1902 Hagestein 1815-1902 Hardenbroek 1811 Harmelen 1811-1912 Heemstede 1811 Hoenkoop 1811-1912 Hoogland 1811-1912 Houten 1811-1912 IJsselstein 1811-1912 Indijk 1811, 1818-1821 Isselt 1811 Jaarsveld 1811-1912 Jutphaas 1811-1912 Kabauw 1818-1857 Kamerik 1858-1912 Kamerik Houtdijken 1811, 1818-1857 Kamerik-Mijzijde 1811-1857 Kockengen 1811-1912 Laagnieuwkoop 1818-1912 Langbroek 1811-1912 Leersum 1811-1912 Leusden 1811-1912 Linschoten 1812-1912 Loenen 1811-1817, 1820-1912 Loenen Kronenburg 1818-1819 (Hollands) Loenen Nieuwersluis 1818-1819 (Stichts) Loenersloot 1811-1912 Lopik 1811-1912 Maarn 1811, 1818-1912 Maarssen 1811-1912 Maarssenbroek 1818-1857 Maarsseveen 1811-1912 Maartensdijk 1811-1912 Mijdrecht 1811-1912 Mijnden 1811 Montfoort 1811-1912 Nederlangbroek 1811 Nieuw-Maarsseveen 1811 Nigtevecht 1811, 1818-1912 Odijk 1811, 1818-1912 Oud-Maarsseveen 1811 Oud-Wulven 1818-1857 -

Utrecht, the Netherlands

city document Utrecht, The Netherlands traffic, transport and the bicycle in Utrecht URB-AL R8-P10-01 'Integration of bicycles in the traffic enginering of Latin American and European medium sized cities. An interactive program for education and distribution of knowledge' European Commission EuropeAid Co-operation Office A study of the city of Utrecht, the Netherlands The tower of the Dom church and the Oudegracht canal form the medieval heart of Utrecht. 1 Introduction 1.1 General characteristics of the city Utrecht is, after Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague, the fourth largest city in the Netherlands, with a population of approximately 258,000. Utrecht is the capital city of the province of Utrecht. The city lies in the heart of the Netherlands, at an intersection of roads, railways and waterways. The city is very old: it was founded by the Romans in around 47 AD. The city was at that time situated on the Rhine, which formed the northern frontier of the Roman Empire. The city is located in flat country, surrounded by satellite towns with grassland to the west and forested areas to the east. Utrecht forms part of “Randstad Holland”, the conurbation in the west of the Netherlands that is formed by the four large cities of the Netherlands and their satellite towns. Symbols for old Utrecht: Dom church and the Oudegracht canal. 1 The Netherlands is densely populated, with a total population of around 16 million. The population density is 457 inhabitants per km2. A closely-knit network of motorways and railways connects the most important cities and regions in the Netherlands. -

Buren Van Rijnenburg En Reijerscop) Raadsvoorstel Gemeente Woerden - Afwegingskader Grootschalige Duurzame Energie 1 Juni 2021

BVRR advies (Buren van Rijnenburg en Reijerscop) Raadsvoorstel Gemeente Woerden - Afwegingskader grootschalige duurzame energie 1 juni 2021 Utrecht, 22 juni 2021 Geachte Raadsleden, Met grote interesse hebben wij als Buren van Rijnenburg en Reijerscop (BVRR) kennis genomen van het Raadsvoorstel en Afwegingskader grootschalige duurzame energie van 1 juni 2021. Omdat wij in de discussie over het Energielandschap Rijnenburg en Reijerscop sinds 2017 in de gemeente Utrecht met dezelfde vragen zijn geconfronteerd die nu in uw gemeente spelen willen wij graag op grond van onze ervaringen een kort Advies aan u voorleggen om tot een Wijziging van het Raadsvoorstel te komen. Ons Wijzigingsadvies is Stel de Opgave voor 2030 van de gemeente Woerden voor opwekking van duurzame energie met 1/3 naar beneden bij van 42 GWH kleinschalig en 70 GWh grootschalig naar 42 GWh kleinschalig en 35 GWh grootschalige opwek. Hiermee levert Woerden nog steeds een proportionele bijdrage aan het bereiken van de klimaatdoelen. Met ons voorstel kunnen de omstreden megaturbines in Reijerscop uit het voorstel worden geschrapt. Motivering voor neerwaartse bijstelling van de opgave voor 2030 In de voorgestelde opgave wil Woerden samen met de Lopikerwaard gemeenten (Oudewater, IJsselstein , Lopik en Montfoort) een gezamenlijke bijdrage leveren van 260 GWh aan de RES van de U-16 waarvan het doel op 1,8 TWh is gesteld. De 30 regio’s moeten gezamenlijk een bijdrage leveren van 35 TWh om aan de Klimaatdoelen te voldoen. De gemiddelde bijdrage is 1,2 TWh. Daarom is de RES doelstelling van de U-16 namelijk 1,8 TWh buitenproportioneel. Het aanbod van de RES U-16 is 1/3 hoger dan nodig is om de klimaatdoelen te halen. -

Laag Sociaal-Economisch Niveau

Zuid Schets van het gezondheids-, geluks- en welvaartsniveau en de rol van de Eerstelijn Erik Asbreuk, Voorzitter EMC Nieuwegein, Huisarts Gezondheidscentrum Mondriaanlaan 'Nieuwegein 2020: gezond, gelukkig en welvarend?' Rapport Rabobank 2010: Nieuwegein, de werkplaats van Midden Nederland: Nieuwegein heeft een laag sociaal-economisch niveau Zuid % lopende WW uitkeringen op 1 januari (tov potentiële beroepsbevolking) Amersfoort Baarn Bunnik Bunschoten De Bilt De Ronde Venen Eemnes Gemiddelde Houten IJsselstein Leusden Lopik Montfoort Nieuwegein Oudewater Renswoude Rhenen Soest Stichtse Vecht Utrechtse Heuvelrug Veenendaal Vianen Wijk bij Duurstede Woerden Woudenberg Zeist 0 0,5 1 1,5 2 2,5 % lopende WW uitkeringen op 1 januari (tov potentiële beroepsbevolking) Amersfoort Baarn Bunnik Bunschoten De Bilt De Ronde Venen Eemnes Gemiddelde Houten IJsselstein Leusden Lopik Montfoort Nieuwegein Oudewater Renswoude Rhenen Soest Stichtse Vecht Utrechtse Heuvelrug Veenendaal Vianen Wijk bij Duurstede Woerden Woudenberg Zeist 0 0,5 1 1,5 2 2,5 % WAO ontvangers (tov potentiële beroepsbevolking) Amersfoort Baarn Bunnik Bunschoten De Bilt De Ronde Venen Eemnes Gemiddelde Houten IJsselstein Leusden Lopik Montfoort Nieuwegein Oudewater Renswoude Rhenen Soest Stichtse Vecht Utrechtse Heuvelrug Veenendaal Vianen Wijk bij Duurstede Woerden Woudenberg Zeist 0 0,5 1 1,5 2 2,5 3 3,5 4 4,5 5 % WAO ontvangers (tov potentiële beroepsbevolking) Amersfoort Baarn Bunnik Bunschoten De Bilt De Ronde Venen Eemnes Gemiddelde Houten IJsselstein Leusden Lopik Montfoort Nieuwegein Oudewater Renswoude Rhenen Soest Stichtse Vecht Utrechtse Heuvelrug Veenendaal Vianen Wijk bij Duurstede Woerden Woudenberg Zeist 0 0,5 1 1,5 2 2,5 3 3,5 4 4,5 5 Laag sociaal-economisch niveau • In vergelijking met de regio is het sociaal economisch niveau van de bevolking van Nieuwegein laag. -

Achthoven Barwoutswaarder En

ACHTHOVEN OMSCHRIJVING PLAATS BURG./KERK. PERIODE INDEXNR. KOPIE ORIGINEEL DTB / Burgerlijke Stand Burgerlijke Stand: Geboorte Achthoven Burgerlijk 1818-1857 Alg. 13-15 + website Microfiches Burgerlijke Stand: Geboorte Heeswijk Burgerlijk 1811-1811 Alg. 13-15 + website Trouwen Achthoven Burgerlijk (rechterlijk) 1733-1809 M4 Microfiches vanaf 1763 Trouwen Heeswijk Burgerlijk (rechterlijk) 1714-1809 M4 Microfiches Burgerlijke Stand: Huwelijk Achthoven Burgerlijk 1818-1857 Alg. 16-17 + website Microfiches Burgerlijke Stand: Overlijden Achthoven Burgerlijk 1811, 1818-1857 Alg. 18-20 + website Microfiches Bevolkingsregistratie Volkstellingen Achthoven Burgerlijk 1837-1857 M2 + website Microfiches Bevolkingsregisters Achthoven Burgerlijk 1850-1860 M2 + website Microfiches Armenzorg Akten van indemniteit Achthoven Burgerlijk 1764-1807 Website Akten van indemniteit Heeswijk Burgerlijk 1748-1811 Website BARWOUTSWAARDER EN BEKENES OMSCHRIJVING PLAATS BURG./KERK. PERIODE INDEXNR. KOPIE ORIGINEEL DTB / Burgerlijke Stand Burgerlijke Stand: Geboorte Barwoutswaarder Burgerlijk 1818-1932 Alg. 13-15 + website* Microfiches Trouwen Barwoutswaarder Burgerlijk (belasting) 1759-1804 Alg. 10-12 Gaarder Bww Rtv 1 Burgerlijke Stand: Huwelijk Barwoutswaarder Burgerlijk 1818-1932 Alg. 16-17 + website Microfiches Burgerlijke Stand: Huwelijk Barwoutswaarder Burgerlijk 1933-1942 Website Microfiches Begraven Barwoutswaarder Burgerlijk (belasting) 1759-1804 W1 + website Gaarder Bww Rtv 1 Begraven Bekenes Burgerlijk (belasting) 1759-1804 W1 + website Gaarder Bww Rtv 1 Burgerlijke Stand: Overlijden Barwoutswaarder Burgerlijk 1818-1950 Alg. 18-21 + website Microfiches Burgerlijke Stand: Overlijden Barwoutswaarder Burgerlijk 1951-1960 Website N.B. *De index op de website gaat tot en met 1912. Bevolkingsregistratie Volkstellingen Barwoutswaarder Burgerlijk 1837, 1840, 1846 W2 Microfiches Bevolkingsregisters Barwoutswaarder Burgerlijk 1850-1940 W2 + website* Microfiches Bevolkingsregisters Bekenes Burgerlijk 1882-1919 W2 Microfiches N.B. *Alleen de periode 1850-1881 staat op de website. -

Woerden Veenendaal UTRECHT Zeist Amersfoort Nieuwegein

! ! ! ! ! ! PROVINCIALE RUIMTELIJKE STRUCTUURVISIE ! 2013 - 2028 (HERIJKING 2016) ! Abcoude KAART 1 - EXPERIMENTEERRUIMTE ! ! ! ! Eiland van Schalkwijk (toelichtend) ! ! ! ! ! Eemnes ! 0 10 km ! Spakenburg ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bunschoten Vastgesteld door Provinciale Staten van Utrecht op 12 december 2016 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Baarn ! Vinkeveen ! ! Mijdrecht ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Breukelen ! Soest ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Amersfoort ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Maarssen ! ! ! ! ! ! Bilthoven ! ! ! Leusden ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Vleuten De Bilt ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Zeist Woudenberg ! UTRECHT ! Woerden ! ! ! De Meern ! ! Bunnik ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Driebergen-Rijsenburg ! ! ! ! ! Mo! ntfoort ! Doorn Oudewater! Nieuwegein ! ! Houten Veenendaal ! IJsselstein ! ! ! ! Leersum ! ! ! Amerongen ! ! ! ! ! Vianen ! ! ! Wijk bij ! ! ! ! Duurstede ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Rhenen ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! AFDELING FYSIEKE LEEFOMGEVING, TEAM GIS ONDERGROND: © 2017, DIENST VOOR HET KADASTER EN OPENBARE REGISTERS, APELDOORN 12-12-2016 PRS PROVINCIALE RUIMTELIJKE STRUCTUURVISIE 2013 - 2028 (HERIJKING 2016) Abcoude KAART 2 - BODEM veengebied kwetsbaar voor oxidatie (toelichtend) Eemnes Spakenburg duurzaam gebruik van de ondergrond veengebied gevoelig voor bodemdaling Bunschoten 0 10 km Vastgesteld door Provinciale Staten van Utrecht op 12 december 2016 Vinkeveen Baarn Mijdrecht Breukelen Soest Amersfoort Maarssen Bilthoven Leusden Vleuten De Bilt Zeist Woudenberg UTRECHT Woerden De Meern Bunnik Driebergen-Rijsenburg Montfoort Doorn Oudewater Nieuwegein Houten -

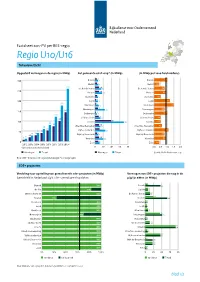

Factsheet Zon-PV U10-U16 PDF Document

Factsheet zon-PV per RES-regio Regio U10/U16 Totaaloverzicht Opgesteld vermogen in de regio (in MWp) Per gemeente eind 2019* (in MWp) (In MWp per 1000 huishoudens) 4 Bunnik 7 Bunnik 1,0 5 De Bilt 8 De Bilt 0,4 258 10 De Ronde Venen 15 De Ronde Venen 0,8 10 Houten 17 Houten 0,9 5 IJsselstein 7 IJsselstein 0,5 3 Lopik 7 Lopik 1,2 176 3 Montfoort 9 Montfoort 1,5 7 Nieuwegein 24 Nieuwegein 0,8 142 Oudewater 2 Oudewater 1,0 120 5 Stichtse Vecht 9 Stichtse Vecht 0,5 100 13 Utrecht 39 Utrecht 0,5 80 70 74 10 0,6 60 Utrechtse Heuvelrug 13 Utrechtse Heuvelrug 53 11 Vijeerenlanden 25 Vijeerenlanden 1,1 41 41 28 29 5 0,8 20 Wijk bij Duurstede 8 Wijk bij Duurstede 8 12 10 Woerden 20 Woerden 0,9 8 Zeist 11 Zeist 0,4 * *(per einde van het kalenderjaar) , , , , , Woningen Totaal Woningen Totaal Gemiddeld in Nederland: 0,9 Bron: CBS – Zonnestroom: opgesteld vermogen *voorlopige cijfers SDE+ projecten Verdeling naar opstelling van gerealiseerde sde+ projecten (in MWp) Vermogen van SDE+ projecten die nog in de Gemiddeld in Nederland: 63% SDE+ gerealiseerd op daken pijplijn zitten (in MWp) 6 Bunnik 100% Bunnik 37 7 De Bilt 83% De Bilt 7 12 De Ronde Venen 100% De Ronde Venen 12 20 Houten 24% Houten 54 3 IJsselstein 100% IJsselstein 3 4 Lopik 100% Lopik 4 7 Montfoort 100% Montfoort 7 36 Nieuwegein 70% Nieuwegein 41 3 Oudewater 100% Oudewater 3 11 Stichtse Vecht 100% Stichtse Vecht 11 74 Utrecht 100% Utrecht 74 5 Utrechtse Heuvelrug 100% Utrechtse Heuvelrug 6 37 Vijeerenlanden 100% Vijeerenlanden 37 3 Wijk bij Duurstede 100% Wijk bij Duurstede -

Besluit Bodemkwaliteit Nota Bodembeheer Utrecht ZW Definitief Extern (Odt)

Inhoudsopgave 1 Inleiding.......................................................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Aanleiding en doelstelling..............................................................................................................................1 1.2 Afbakening nota bodembeheer.....................................................................................................................1 1.2.1 Geldigheid............................................................................................................................................1 1.2.2 Toepassingsgebied.............................................................................................................................2 1.3 Leeswijzer........................................................................................................................................................2 2 Wettelijke en beleidsmatige achtergronden...........................................................................................................3 2.1 Wet en regelgeving.........................................................................................................................................3 2.1.1 Besluit en Regeling bodemkwaliteit.................................................................................................3 2.1.2 Wet bodembescherming (Wbb).........................................................................................................4 -

Woonvisie (Pdf)

Woonvisie 2025 DE RONDE VENEN POSTADRES Postbus 250 T 0297 29 16 16 3640 AG Mijdrecht F 0297 28 42 81 BEZOEKADRES Croonstadtlaan 111 E [email protected] 3641 AL Mijdrecht I www.derondevenen.nl AUTEUR(S) Emily Joynes DATUM Mei 2017, gewijzigd vastgesteld maart 2020 STATUS Vastgesteld door gemeenteraad Woonvisie De Ronde Venen Voorwoord Of je nu vaart, fietst, loopt of eenvoudigweg naar school of werk gaat. De Ronde Venen is prachtig! En telkens verbaas ik me er weer over hoe snel ik in de stad ben. Binnen een half uur sta ik op de Dam in Amsterdam of onder de Dom in Utrecht. Dat maakt De Ronde Venen een unieke plek. Je kunt er thuis komen en je rust vinden. En tegelijkertijd gonst het ook binnen de gemeente van bedrijvigheid. Wie door de gemeente rijdt, ziet overal bouwactiviteiten. In 2016 is het startsein gegeven voor de bouw van drie grote woningbouwprojecten in de gemeente: Vinkeveld, De Maricken en Land van Winkel. Er wordt volop gebouwd voor alle inkomens en leeftijden. Koop en sociale huur. Toegankelijke woningen voor starters. Woningen voor mensen die een volgende woonstap zetten. Comfortabele levensbestendige woningen voor senioren. Voor iedereen is er een woning. Onze jongeren blijven graag in de gemeente wonen of keren terug na hun studie. Jonge gezinnen die de stad ontvluchten vinden hier ruimte en betaalbare woningen. Ouderen kunnen hier in hun vertrouwde omgeving blijven wonen in passende woonruimte. En met het aantrekken van jonge gezinnen uit de regio blijven we een vitale en economische sterke gemeente. Wij blijven werken aan een goed woonaanbod. -

Gemeentelijke Monumenten

Gemeentelijke monumenten Kern Adres Nummer Postcode Naam Aangewezen Categorie Harmelen Breudijk 27 3481 LM Elisabeth Woutrina Hoeve 2004 Langhuisboerderij Harmelen Breudijk 29 3481 LM Johanna Hoeve 2000 Langhuisboerderij Harmelen Dorpsstraat 30 3481 EL - 2004 Woonhuis/winkel Harmelen Dorpsstraat 35 3481 EA Huis Landzigt 2004 Woonhuis Harmelen Dorpsstraat 42 3481 EL - 2000 Woonhis/winkel Harmelen Dorpsstraat Achter 70 3481 EN St.-Bravokapel (Gazakapel) 1998 Kerkgebouw- en onderdeel Harmelen Dorpsstraat 81 3481 EB - 2004 Woonhuis/winkel Harmelen Dorpsstraat 103 3481 EC Tolhuis 2004 Woonhuis/horeca Harmelen Dorpsstraat 164 3481 ER - 2004 Woonhuis Harmelen Dorpsstraat 166 3481 ER - 2004 Woonhuis Harmelen Dorpsstraat 187 3481 EE - 2004 Woonhuis Harmelen Gerverscop 9 3481 LT Baron van Wassenaar Hoeve 2004 Langhuisboerderij Harmelen Gerverscop 13-13A 3481 LT - 2004 Dwarshuisboerderij Harmelen Gerverscop 27 3481 LV - 2002 Langhuisboerderij Harmelen Haanwijk 15 3481 LH Eikenstein 2000 Herenboerderij Harmelen Haanwijk 17 3481 LH - 2004 Langhuisboerderij Harmelen Jaagpad 5 en 6 3481 ET - 2004 Woonhuis Harmelen Jaagpad 16 3481 ET - 2004 Woonhuis Harmelen Leidsestraatweg 35-37 3481 EV Villa Vredehof 2000 Woonhuis Harmelen Leidsestraatweg 39 3481 EV - 2004 Langhuisboerderij Harmelen Reijerscop 16 3481 LE - 2004 Langhuisboerderij Harmelen Reijerscop 28 3481 LE Landlust 2000 Langhuisboerderij Harmelen Uitweg ong. n.v.t. Kwakelbrug 2002 Weg- en waterwerken Kamerik ’s-Gravensloot 19 en 20 3471 BM Buitenlust 1991 Dwarshuisboerderij Kamerik ’s-Gravensloot