MEIEA 2017 Color.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Revenue Ordinance

2021 Revenue Ordinance As Proposed on December 5, 2019 ii Revenue Ordinance of 2021 to Levy Taxes and Fees and Raise Revenue For the City of Savannah Georgia As adopted on December 18, 2020 Published by City of Savannah Revenue Department Post Office Box 1228 Savannah, GA 31402-1228 CITY OF SAVANNAH 2021 CITY COUNCIL Mayor Van R. Johnson, II Post 1 At-Large Post 2 At-Large Kesha Gibson-Carter Alicia Miller Blakely District 1 District 2 Bernetta B. Lanier Detric Leggett District 3 District 4 Linda Wilder-Bryan Nick Palumbo District 5 District 6 Dr. Estella Edwards Shabazz Kurtis Purtee Revenue Ordinance Compiled By Revenue Director/City Treasurer Ashley L. Simpson Utility Billing Manager Nicole Brantley Treasury Manager Joel Paulk Business Tax & Alcohol License Manager Judee Jones Revenue Special Projects Coordinator Saja Aures Table of Contents Revenue Ordinance of 2021 ....................................................................................................................... 1 ARTICLE A. GENERAL ............................................................................................................................... 1 Section 1. SCOPE; TAXES AND FEES .................................................................................................... 1 Section 2. DEFINITIONS ........................................................................................................................... 1 Section 3. JANUARY 1 GOVERNS FOR YEAR ...................................................................................... -

CALLAND CLEMENTS ZOMNIR Linpsavr

CALLAND CLEMENTS ZOMNIR LINPSAVr. HOVC'ARP May 14, 1999 VIA FEDERAL EXPRESS Frank Klanchar (3HW22) United States Environmental Protection Agency Region III 841 Chestnut Building Philadelphia, PA 19107-4431 RE: Welsh Road/Bartaan Landfill Superfund Site Administrative Order for Remedial Action (Docket No. III-99-012-DC) Dear Mr. Klanchar: I. Introduction On or about March 19, 1999, the United States Environmental Protection Agency ("EPA" or the "Agency") issued an Administrative Order for Remedial Action (Docket No. III-99-012-DC) (the "Order") to fourteen (14) respondents (collectively, the "Respondents"), including Ecolaire Incorporated ("Ecolaire"), directing those parties to, inter .alia, implement certain remedial activities at the Welsh Road Superfund Site located in Chester and Lancaster Counties, Pennsylvania (the "Site"). Pursuant to Section XXV of the Order, EPA directed each Respondent to provide notice to EPA's Remedial Project Manager stating whether the Respondents would comply with the terms of the Order. Although the Order required such notice to be provided no later than two (2) days after the effective date of the Order, through mutual agreement among the parties, this deadline was extended to May 17, 1999. The purpose of this letter is to communicate Ecolaire's current intentions with respect to the Order, and, subject to the reservations below, to set forth a description of the "sufficient cause" defenses that are known to Ecolaire at the time of this letter. See Sections 106 and 107 of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act ("CERCLA"), 42 U.S.C. §§9606;and 9607." """ Twu Gareviii\ Center ir-ih, P«nn*vK.mici 4i: «4o40C " Fax 41- ^4-6576' AROUI725 Frank Klanchar May 14, 1999 Page 2 II. -

Marc Shapiro

ADELE The Biography MARC SHAPIRO ST. MARTIN’S GRIFFIN NEW YORK adele. Copyright © 2012 by Marc Shapiro. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010. www .stmartins .com Design by Steven Seighman ISBN 978- 1- 250- 02516- 6 (trade paperback) ISBN 978- 1- 250- 02547- 0 (hardcover) ISBN 978- 1- 250- 02515- 9 (e-book) First Edition: July 2012 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 10. NO BALLAD, NO CRY dele began writing new material for her follow- up record in April 2009. But not before she agreed to take a fl yer as an actress with a guest shot on the hit tele vi- sion sitcom Ugly Betty. It seemed like a harm- Aless diversion from all the drama and pressure in her life. She reasoned, how hard could it be to play herself? In the episode, Betty is dancing with her husband at their wedding when the couple is suddenly interrupted by Adele. Th ere is some harmless banter and the next thing we know Adele is up on stage singing the song “Right As Rain.” Adele realized that that kind of promotion in America was well worth the eff ort, but would later acknowledge in Vogue that the Ugly Betty experience cured her of any future acting aspirations. “I can’t watch it. I was so uncomfortable. I am the worst actress of all time.” But Adele was thankful for the momentary respite from Marc Shapiro her day job as singer-songwriter on the rise. -

Willie Nelson

LESSON GUIDE • GRADES 3-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Introduction 4 About the Guide 5 Pre and Post-Lesson: Anticipation Guide 6 Lesson 1: Introduction to Outlaws 7 Lesson 1: Worksheet 8 Lyric Sheet: Me and Paul 9 Lesson 2: Who Were The Outlaws? 10 Lesson 3: Worksheet 12 Activities: Jigsaw Texts 14 Lyric Sheet: Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way 15 Lesson 4: T for Texas, T for Tennessee 16 Lesson 5: Literary Lyrics 17 Lyric Sheet: Daddy What If? 18 Lyric Sheet: Act Naturally 19 Complete Tennessee Standards 21 Complete Texas Standards 23 Biographies 3-6 Table of Contents 2 Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s examines how the Outlaw movement greatly enlarged country music’s audience during the 1970s. Led by pacesetters such as Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Bobby Bare, artists in Nashville and Austin demanded the creative freedom to make their own country music, different from the pop-oriented sound that prevailed at the time. This exhibition also examines the cultures of Nashville and fiercely independent Austin, and the complicated, surprising relationships between the two. Artwork by Sam Yeates, Rising from the Ashes, Willie Takes Flight for Austin (2017) 3-6 Introduction 3 This interdisciplinary lesson guide allows classrooms to explore the exhibition Outlaws and Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s on view at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum® from May 25, 2018 – February 14, 2021. Students will examine the causes and effects of the Outlaw movement through analysis of art, music, video, and nonfiction texts. In doing so, students will gain an understanding of the culture of this movement; who and what influenced it; and how these changes diversified country music’s audience during this time. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

Chance the Rapper's Creation of a New Community of Christian

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book Samuel Patrick Glenn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Glenn, Samuel Patrick, "“Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book" (2020). Honors Theses. 336. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/336 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Religious Studies Department Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Samuel Patrick Glenn Lewiston, Maine March 30 2020 Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge my thesis advisor, Professor Marcus Bruce, for his never-ending support, interest, and positivity in this project. You have supported me through the lows and the highs. You have endlessly made sacrifices for myself and this project and I cannot express my thanks enough. -

Best Gay Songs: 30–21 30

Best gay songs: 30–21 30 “City Grrrl” by CSS Bad girls and gay boys have always been besties, and this 2011 track from Brazilian combo Cansei de Ser Sexy is a loving ode to that special relationship. Lead singer Lovefoxxx looks back on adolescent fantasies of "being busy with my job and my gay friends, laughing and drinking with my one-night stands" in the "big city." Anyone who's ever felt trapped in a small town (and eventually escaped) will definitely relate. —Ethan LaCroix Download on Amazon www.youtube.com/watch?v=duOA3FgpZqY 29 “Your Loving Arms” by Billie Ray Martin Most gay dance anthems are packed with drama of both the lyrical and vocal variety. But in 1994, German singer Billie Ray Martin invaded clubland with this icy floor filler that's so calm she almost seems detached. Don't let that near-monotone fool you, though—Martin is a formidable vocalist, and when she finally cuts loose ("Burning inside, burning inside, yeah!"), it's a master class in the art of delayed gratification.—Ethan LaCroix Download on Amazon www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVukIhibLYM 28 “Viz” by Le Tigre Before forming her dance-DJ-production project MEN, JD Samson stepped up to the mike as a member of this electro-rock trio. "Viz" (2004), about butch-lesbian visibility, offers an early glimpse of Samson's sly humor and her ability to make radical queer politics into dance-floor fodder. Bandmates Kathleen Hanna and Johanna Fateman join in on the final chorus for a joyous feminist sing-along.—Ethan LaCroix Download on Amazon www.youtube.com/watch?v=vMcCNzUyG5I 27 “The Jean Genie” by David Bowie The copper mullet, the lightning bolt across the face—in 1972, Bowie was at the peak of his androgynous alien phase, pushing Ziggy Stardust closer to the sun until he incinerated in a flash. -

Work It Missy Elliott Free Download

Work it missy elliott free download click here to download Free download Work It – Miss Elliot Mp3. We have about 25 mp3 files ready to play and Filename: Work it-Missy elliot (Backward).mp3. Work It. Artist: Missy Elliott. www.doorway.ru MB · Work It. Artist: Missy Elliott. www.doorway.ru MB · Work It. Artist: Missy Elliott. Missy Elliott - Work It (Dj Sliink & R4 Remix) Missy Elliott - Work It (Remix) ft. 50 Cent Missy Elliott - Work It (White Label Breakbea Missy Elliott - Work It (White. Work It Missy Eliot Free Mp3 Download. Free Missy Elliott Work It Official www.doorway.ru3. Play & Download Size MB ~ ~ kbps. Free Missy Elliot. Missy Elliott - Work It mp3 free download for mobile. Stream 'Work It' Ft Missy Elliott (FREE DOWNLOAD) by Daniel Chapman - Free Downloads from desktop or your mobile device. WORK IT MISSY ELLIOT MP3 Download ( MB), Video 3gp & mp4. List download link Lagu MP3 WORK IT MISSY ELLIOT ( min), last update Sep Watch the video, get the download or listen to Missy Elliott – Work It for free. Work It appears on the album Under Construction. "Work It" is a hip hop song written. 50 Cent Feat. Missy Elliot Work It (Remix) [Prod. by Timbaland] free mp3 download and stream. Missy Eliot Work It Out Download Free Mp3 Song. Missy Elliott - Work It (Official Video) mp3. Quality: Good Download. Missy Elliot Work It Lyrics mp3. Quality. Buy Work It: Read 26 Digital Music Reviews - www.doorway.ru Missy Elliott Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this song plus tens of millions. -

Gautier Detective's Passion Writing, Singing Songs | Gulflive.Com

Gautier detective's passion writing, singing songs | gulflive.com http://blog.gulflive.com/mississippi-press-living//print.html Gautier detective's passion writing, singing songs By Kevin Saucier June 01, 2010, 5:11AM Gautier Police Detective Matt Hoggatt plays his music at The Shed Barbeque and Blues Joint PASCAGOULA - When Detective Matt Hoggatt of the Gautier Police Department is not doing police work or hanging out with his family, he is actively pursuing his passion: songwriting. Hoggatt started playing guitar and writing songs in 2005, but that was not his first foray into music. Hoggatt has been a musician since he started playing trumpet in seventh grade at Gautier Middle School. He continued to play trumpet in the marching band at Pascagoula High School, and then he picked up the baritone at the Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College. He later served in the Mississippi National Guard for seven years, playing trumpet and baritone in the National Guard band. "They say if you join the military you get to see the world," Hoggatt said. "If you join the National Guard you get to see the state. So I went everywhere in Mississippi you can possibly go, all the way up to the north, south, east and west, and pretty much once a month we'd play a gig somewhere. We were in all kinds of parades, festivals, fishing rodeos, you name it." Though none of his songs have been purchased, Hoggatt won a contest held by American Songwriter Magazine with a song he wrote called "21 at Normandy," and he was rewarded with a full-page interview. -

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 7/8/2020 Semisonic “You’re Not Alone” The first single from their You’re Not Alone EP, out 9/18 BDS Monitored #1 Most Added before add week! Early: KCMP, KCSN, WRNR, WXPK, WFUV, WTMD, WFPK, KTBG, Music Choice, WPYA, WOCM, KYSL, WFIV, WJCU, KNBA, KSLU, WUKY, WOXL This is their first new music in almost 20 years Tons of great press “Like their greatest hits of yesteryear” - Consequence of Sound Margo Price “Letting Me Down” The first single That’s How Rumors Get Started, produced by Sturgill Simpson, out this Friday Appeared on CBS This Morning BDS Monitored New & Active, JBE Tracks 49*, Public 23*! New: WEVL ON: WRLT, WFUV, WXPN, Music Choice, WYEP, WFPK, WTMD, KTBG, KJAC, WRSI and more Tons of recent and upcoming press Watch the creative video on my site now Buzzard Buzzard Buzzard “Double Denim Hop” The first single from The Non-Stop EP, out this Friday New: WCNR, WYCE ON: KCSN, KJAC, WCLX, WCBE, WBJB, WOCM, WFIV, KROK “Think Thin Lizzy or T-Rex in the back room of a pub, riffs and tunes intact but with an endearing slacker attitude.” - The Guardian Great UK press! Topping the Alt Press list of the Best New British Guitar-Rock Bands: “Theirs is the ground floor to be on, friends.” Joshua Speers “Bad Night” From his Human Now EP, out now New: WYCE, KROK, WCBE, KSLU ON: KSMF, KCLC, WFIV, KUWR “The five-track project is such an enamoring listen, kind of perfect for quarantine, whether with a cup of coffee—or whiskey.. -

Lady Miss Kier

Lady Miss Kier Kier Kirby más conocida como Lady Miss Kier, mÃtica vocalista, co-productora y bailarina de los no menos mÃticos Deee Lite. Este combo neoyorquino con talante cosmopolita fue fundado en 1986 por la propia Kier y Super Dj Dimitry, a quienes poco después se unió Towa Tey conformando el núcleo definitivo de esa máquina de fabricar hits para las pistas de baile. Su primer single \"Groove Is In The Heart\", editado en el 91, que paso de ser un white label para dj\'s a vender millones de copias, significaba un equilibrio perfecto entre las demandas del mercado pop y las necesidades de las pistas de baile, resumiendo el hedonismo quÃmico de aquella época. Su debut en formato álbum \"World Clique\" llegó poco después, un trabajo que ellos mismo calificaron como \"holographic techno soul\" y que fusionaba p funk, breaks, house y techno. La Kier ejerció además de estilista y directora de arte del grupo, asumiendo desde el diseño de vestuario hasta el concepto de los videos y el diseño gráfico. Su segundo álbum, \"Infinity Within\", llegó un año más tarde y constituÃa un disco de protesta en contra de la guerra del golfo y a favor del pacifismo. Musicalmente continuaba profundizando en las premisas Deee Lite aunque se orientaba hacia un contexto ligeramente más electrónico. Su último álbum oficial fue \"Dewdrop In The Garden\" (1994) -a parte del recopilatorio de rarezas \"Sampladelic Relics & Dancefloor Oddities\" (1996)- un ejercicio de liberación sexual alimentado de sustancias alucinógenas que marcaba el punto final en la trayectoria de una banda genial e inclasificable. -

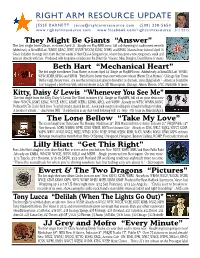

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 3/11/2015 They Might Be Giants “Answer” The first single from Glean, in stores April 21 Single on PlayMPE now, full cd shipping to radio next month Added early at SiriusXM Loft, WNKU, KBAC, WFIV, WVMP, WOCM, KUNC, WHRV and KFMG National tour kicks off April 16 Glean includes 16 songs from their the first weeks of their Dial-A-Song service, where they post a new song every week and interact directly with fans. Produced with long-time collaborator Pat Dilett (St. Vincent, Mike Doughty, David Byrne & more) Beth Hart “Mechanical Heart” The first single from Better Than Home, in stores April 14 Single on PlayMPE now Added early at SiriusXM Loft, WNKU, WFIV, KDBB, KFMG and KRVM “Beth Hart is better than ever with new release (Better Than Home)”- Chicago Sun Times “Beth’s tough, throaty voice…she uses that powerful instrument to best effect on dramatic, arena filling ballads.” – American Songwriter Just wrapped a brief tour with sold out shows in LA, SF, Minneapolis, Chicago, Akron, Boston, NYC, Nashville & more Kitty, Daisy & Lewis “Whenever You See Me” The first single from the Kitty, Daisy & Lewis The Third, in stores 3/31 Single on PlayMPE, full cd on your desk now New: WNCW, KSMT, KBAC, WYCE, KRCC, KSMF, WERU, KDNK, KRCL and WHRV Already on WFIV, WNRN, KUNC Produced by The Clash’s Mick Jones “A joyfully punchy, musical kiss off… A real punk energy in this sibling trio’s brand of rocking revivalism…