1 Directors and Officers' Risks, Liability and Insurance Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socially Conscious Australian Equity Holdings

Socially Conscious Australian Equity Holdings As at 30 June 2021 Country of Company domicile Weight COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIA 10.56% CSL LTD AUSTRALIA 8.46% AUST AND NZ BANKING GROUP AUSTRALIA 5.68% NATIONAL AUSTRALIA BANK LTD AUSTRALIA 5.32% WESTPAC BANKING CORP AUSTRALIA 5.08% TELSTRA CORP LTD AUSTRALIA 3.31% WOOLWORTHS GROUP LTD AUSTRALIA 2.93% FORTESCUE METALS GROUP LTD AUSTRALIA 2.80% TRANSURBAN GROUP AUSTRALIA 2.55% GOODMAN GROUP AUSTRALIA 2.34% WESFARMERS LTD AUSTRALIA 2.29% BRAMBLES LTD AUSTRALIA 1.85% COLES GROUP LTD AUSTRALIA 1.80% SUNCORP GROUP LTD AUSTRALIA 1.62% MACQUARIE GROUP LTD AUSTRALIA 1.54% JAMES HARDIE INDUSTRIES IRELAND 1.51% NEWCREST MINING LTD AUSTRALIA 1.45% SONIC HEALTHCARE LTD AUSTRALIA 1.44% MIRVAC GROUP AUSTRALIA 1.43% MAGELLAN FINANCIAL GROUP LTD AUSTRALIA 1.13% STOCKLAND AUSTRALIA 1.11% DEXUS AUSTRALIA 1.11% COMPUTERSHARE LTD AUSTRALIA 1.09% AMCOR PLC AUSTRALIA 1.02% ILUKA RESOURCES LTD AUSTRALIA 1.01% XERO LTD NEW ZEALAND 0.97% WISETECH GLOBAL LTD AUSTRALIA 0.92% SEEK LTD AUSTRALIA 0.88% SYDNEY AIRPORT AUSTRALIA 0.83% NINE ENTERTAINMENT CO HOLDINGS LIMITED AUSTRALIA 0.82% EAGERS AUTOMOTIVE LTD AUSTRALIA 0.82% RELIANCE WORLDWIDE CORP LTD UNITED STATES 0.80% SANDFIRE RESOURCES LTD AUSTRALIA 0.79% AFTERPAY LTD AUSTRALIA 0.79% CHARTER HALL GROUP AUSTRALIA 0.79% SCENTRE GROUP AUSTRALIA 0.79% ORORA LTD AUSTRALIA 0.75% ANSELL LTD AUSTRALIA 0.75% OZ MINERALS LTD AUSTRALIA 0.74% IGO LTD AUSTRALIA 0.71% GPT GROUP AUSTRALIA 0.69% Issued by Aware Super Pty Ltd (ABN 11 118 202 672, AFSL 293340) the trustee of Aware Super (ABN 53 226 460 365). -

FTSE World Asia Pacific

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE World Asia Pacific Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) a2 Milk 0.04 NEW Asustek Computer Inc 0.1 TAIWAN Cheil Worldwide 0.02 KOREA ZEALAND ASX 0.12 AUSTRALIA Cheng Shin Rubber Industry 0.03 TAIWAN AAC Technologies Holdings 0.05 HONG KONG Atlas Arteria 0.05 AUSTRALIA Chiba Bank 0.04 JAPAN ABC-Mart 0.02 JAPAN AU Optronics 0.08 TAIWAN Chicony Electronics 0.02 TAIWAN Accton Technology 0.07 TAIWAN Auckland International Airport 0.06 NEW China Airlines 0.02 TAIWAN Acer 0.03 TAIWAN ZEALAND China Development Financial Holdings 0.07 TAIWAN Acom 0.02 JAPAN Aurizon Holdings 0.05 AUSTRALIA China Life Insurance 0.02 TAIWAN Activia Properties 0.03 JAPAN Ausnet Services 0.03 AUSTRALIA China Motor 0.01 TAIWAN ADBRI 0.01 AUSTRALIA Australia & New Zealand Banking Group 0.64 AUSTRALIA China Steel 0.19 TAIWAN Advance Residence Investment 0.05 JAPAN Axiata Group Bhd 0.04 MALAYSIA China Travel International Investment <0.005 HONG KONG ADVANCED INFO SERVICE 0.06 THAILAND Azbil Corp. 0.06 JAPAN Hong Kong Advantech 0.05 TAIWAN B.Grimm Power 0.01 THAILAND Chow Tai Fook Jewellery Group 0.04 HONG KONG Advantest Corp 0.19 JAPAN Bandai Namco Holdings 0.14 JAPAN Chubu Elec Power 0.09 JAPAN Aeon 0.2 JAPAN Bangkok Bank (F) 0.02 THAILAND Chugai Seiyaku 0.27 JAPAN AEON Financial Service 0.01 JAPAN Bangkok Bank PCL (NVDR) 0.01 THAILAND Chugoku Bank 0.01 JAPAN Aeon Mall 0.02 JAPAN Bangkok Dusit Medical Services PCL 0.07 THAILAND Chugoku Electric Power 0.03 JAPAN Afterpay Touch Group 0.21 AUSTRALIA Bangkok Expressway and Metro 0.02 THAILAND Chunghwa Telecom 0.17 TAIWAN AGC 0.08 JAPAN Bangkok Life Assurance PCL 0.01 THAILAND CIMB Group Holdings 0.08 MALAYSIA AGL Energy 0.04 AUSTRALIA Bank of East Asia 0.03 HONG KONG CIMIC Group 0.01 AUSTRALIA AIA Group Ltd. -

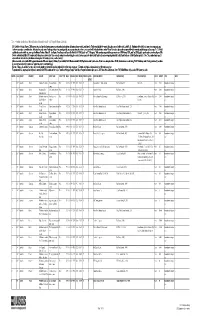

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

Hybrids: Monthly Update - August 2020

Hybrids: Monthly Update - August 2020 Month: Aug-20 Trading days: 21 Period ending: Monday, 31 August 2020 Snapshot by Category Trades Value Australian Segment Bond Segment Number listed Market Cap $b Total (#) Trades per day (#) Volume (#) $m Convertible Preference Shares and Capital Notes 41 38.9 21,947 1,045 4,812,627 488.2 Convertible Bonds 4 0.3 327 16 791,325 5.3 Hybrid Securities 5 3.4 1,594 76 306,338 28.5 Total 50 42.59 23,868 1,137 5,910,290 521.9 Recent Listings Interest Rate / Distribution Entity ASX Code Size ($m) Type Listing Date Issue Price Maturity / Conv / Reset Dividend Frequency Last Price Macquarie Bank Limited MBLPC 641.0 Convertible Preference Shares and Capital03-Jun-2020 Notes $100.00 N/A 4.80% Qtrly $107.00 AMP Limited AMPPB 275.0 Convertible Preference Shares and 24-Dec-2019Capital Notes $100.00 16-Dec-2025 4.60% Qtrly $97.99 Suncorp Group Limited SUNPH 389.0 Convertible Preference Shares and 18-Dec-2019Capital Notes $100.00 17-Jun-2026 3.10% Qtrly $98.80 Clean Seas Seafood Limited CSSG 12.3 Convertible Bonds 18-Nov-2019 $1.00 18-Nov-2022 8.00% S/A $1.04 Commonwealth Bank of Australia CBAPI 1,650.0 Convertible Preference Shares and 15-Nov-2019Capital Notes $100.00 20-Apr-2027 3.10% Qtrly $99.21 Macquarie Group Limited MQGPD 905.5 Convertible Preference Shares and 28-Mar-2019Capital Notes $100.00 10-Sep-2026 4.25% Qtrly $104.85 National Australia Bank Limited NABPF 1,874.1 Convertible Preference Shares and 21-Mar-2019Capital Notes $100.00 17-Jun-2026 4.10% Qtrly $104.43 Westpac Banking Corporation WBCPI 1,423.1 -

Weekly Ratings, Targets, Forecast Changes - 28-05-21

Weekly Ratings, Targets, Forecast Changes - 28-05-21 May 31, 2021 Weekly update on stockbroker recommendation, target price, and earnings forecast changes. By Mark Woodruff Guide: The FNArena database tabulates the views of seven major Australian and international stock brokers: Citi, Credit Suisse, Macquarie, Morgan Stanley, Morgans, Ord Minnett and UBS. For the purpose of broker rating correlation, Outperform and Overweight ratings are grouped as Buy, Neutral is grouped with Hold and Underperform and Underweight are grouped as Sell to provide a Buy/Hold/Sell (B/H/S) ratio. Ratings, consensus target price and forecast earnings tables are published at the bottom of this report. Summary Period: Monday May 24 to Friday May 28, 2021 Total Upgrades: 9 Total Downgrades: 8 Net Ratings Breakdown: Buy 54.81%; Hold 38.67%; Sell 6.52% For the week ending Friday 28 May, there were nine upgrades and eight downgrades to ASX-listed companies by brokers in the FNArena database. After ALS Ltd posted an underlying FY21 profit 4.5% ahead of consensus last week, two brokers in the FNArena database downgraded the company rating due to a strong recent share price. Morgans attributed the result to astute management of costs and capacity, while Morgan Stanley was impressed by momentum in the Commodities segment, but notes the risk with cost inflation. The final dividend of 14.6 cents was well ahead of expectations, underpinned by strong cash conversionFNArena and debt reduction. ALS also achieved the weekly double by appearing atop the tables for the largest positive percentage change to broker’s forecast target prices and earnings. -

ESG Reporting by the ASX200

Australian Council of Superannuation Investors ESG Reporting by the ASX200 August 2019 ABOUT ACSI Established in 2001, the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors (ACSI) provides a strong, collective voice on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues on behalf of our members. Our members include 38 Australian and international We undertake a year-round program of research, asset owners and institutional investors. Collectively, they engagement, advocacy and voting advice. These activities manage over $2.2 trillion in assets and own on average 10 provide a solid basis for our members to exercise their per cent of every ASX200 company. ownership rights. Our members believe that ESG risks and opportunities have We also offer additional consulting services a material impact on investment outcomes. As fiduciary including: ESG and related policy development; analysis investors, they have a responsibility to act to enhance the of service providers, fund managers and ESG data; and long-term value of the savings entrusted to them. disclosure advice. Through ACSI, our members collaborate to achieve genuine, measurable and permanent improvements in the ESG practices and performance of the companies they invest in. 6 INTERNATIONAL MEMBERS 32 AUSTRALIAN MEMBERS MANAGING $2.2 TRILLION IN ASSETS 2 ESG REPORTING BY THE ASX200: AUGUST 2019 FOREWORD We are currently operating in a low-trust environment Yet, safety data is material to our members. In 2018, 22 – for organisations generally but especially businesses. people from 13 ASX200 companies died in their workplaces. Transparency and accountability are crucial to rebuilding A majority of these involved contractors, suggesting that this trust deficit. workplace health and safety standards are not uniformly applied. -

Business Leadership: the Catalyst for Accelerating Change

BUSINESS LEADERSHIP: THE CATALYST FOR ACCELERATING CHANGE Follow us on twitter @30pctAustralia OUR OBJECTIVE is to achieve 30% of ASX 200 seats held by women by end 2018. Gender balance on boards does achieve better outcomes. GREATER DIVERSITY ON BOARDS IS VITAL TO THE GOOD GOVERNANCE OF AUSTRALIAN BUSINESSES. FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF PERFORMANCE AS WELL AS EQUITY THE CASE IS CLEAR. AUSTRALIA HAS MORE THAN ENOUGH CAPABLE WOMEN TO EXCEED THE 30% TARGET. IF YOUR BOARD IS NOT INVESTING IN THE CAPABILITY THAT DIVERSITY BRINGS, IT’S NOW A MARKED DEPARTURE FROM THE WHAT THE INVESTOR AND BROADER COMMUNITY EXPECT. Angus Armour FAICD, Managing Director & Chief Executive Officer, Australian Institute of Company Directors BY BRINGING TOGETHER INFLUENTIAL COMPANY CHAIRS, DIRECTORS, INVESTORS, HEAD HUNTERS AND CEOs, WE WANT TO DRIVE A BUSINESS-LED APPROACH TO INCREASING GENDER BALANCE THAT CHANGES THE WAY “COMPANIES APPROACH DIVERSITY ISSUES. Patricia Cross, Australian Chair 30% Club WHO WE ARE LEADERS LEADING BY EXAMPLE We are a group of chairs, directors and business leaders taking action to increase gender diversity on Australian boards. The Australian chapter launched in May 2015 with a goal of achieving 30% women on ASX 200 boards by the end of 2018. AUSTRALIAN 30% CLUB MEMBERS Andrew Forrest Fortescue Metals Douglas McTaggart Spark Group Ltd Infrastructure Trust Samuel Weiss Altium Ltd Kenneth MacKenzie BHP Billiton Ltd John Mulcahy Mirvac Ltd Stephen Johns Brambles Ltd Mark Johnson G8 Education Ltd John Shine CSL Ltd Paul Brasher Incitec Pivot -

2013 Annual Report

SURFACEBELOW THE Some statements in this report are forward-looking statements within the meaning of the US Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Forward-looking statements also include those containing such words as ‘anticipate’, ‘estimates’, ‘should’, ‘will’, ‘expects’, ‘plans’ or similar expressions. Forward-looking statements involve risks and uncertainties that may cause actual outcomes to be different from the forward-looking statements. Important factors that could cause actual results to differ from the forward looking statements include: (a) material adverse changes in global economic, alumina or aluminium industry conditions and the markets served by AWAC; (b) changes in production and development costs and production levels or to sales agreements; (c) changes in laws or regulations or policies; (d) changes in alumina and aluminium prices and currency exchange rates; and (e) the other risk factors summarised in Alumina’s Form 20-F for the year ended 31 December 2012. Unless otherwise indicated, the values in this report are presented in US dollars. CONTENTS 1 2 AT A GLANCE 4 CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S REPORT 8 SUSTAINABILITY AND THE AWAC BUSINESS 10 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE STATEMENT 23 DIRECTORS’ REPORT 28 OPERATING AND FINANCIAL REVIEW 37 REMUNERATION REPORT 71 FINANCIAL REPORT 112 SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION 113 FINANCIAL HISTORY Challenging market conditions continued in 2013, stemming from a well-supplied alumina market, a sustained low international alumina pricing environment and an unfavourable foreign exchange position. Against this backdrop, Alumina Limited improved its results by recording a net profit of US$0.5 million, an increase of US$56.1 million from the previous year. -

Dow Jones Sustainability Australia Index

Effective as of 23 November 2020 Dow Jones Sustainability Australia Index Company Country Industry Group Comment Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited Australia Banks National Australia Bank Limited Australia Banks Westpac Banking Corporation Australia Banks CIMIC Group Limited Australia Capital Goods Brambles Limited Australia Commercial & Professional Services Downer EDI Limited Australia Commercial & Professional Services Tabcorp Holdings Limited Australia Consumer Services The Star Entertainment Group Limited Australia Consumer Services Janus Henderson Group plc United Kingdom Diversified Financials Oil Search Limited Papua New Guinea Energy Woodside Petroleum Ltd Australia Energy Coles Group Limited Australia Food & Staples Retailing Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Corporation Limited New Zealand Health Care Equipment & Services Asaleo Care Limited Australia Household & Personal Products Insurance Australia Group Limited Australia Insurance QBE Insurance Group Limited Australia Insurance Suncorp Group Limited Australia Insurance Addition Amcor plc Switzerland Materials Addition BHP Group Australia Materials Boral Limited Australia Materials Evolution Mining Limited Australia Materials Fletcher Building Limited New Zealand Materials Fortescue Metals Group Limited Australia Materials IGO Limited Australia Materials Iluka Resources Limited Australia Materials Incitec Pivot Limited Australia Materials Newcrest Mining Limited Australia Materials Orocobre Limited Australia Materials Rio Tinto Ltd Australia Materials South32 Limited -

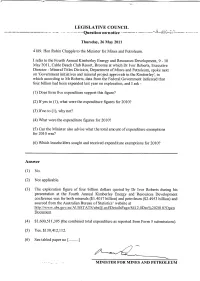

2011-08-09 Qon Exploration Expenditure

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL C 'lff"\ 1"'.( "''1 ---------~~-~Question- on"notice ----------- ..'-?ibt;-:s::'.;"--- --_.- Thursday, 26 May 2011 4189. Hon Robin Chapple to the Minister for Mines and Petroleum. I refer to the Fourth Annual Kimberley Energy and Resources Development, 9 - 10 May 2011, Cable Beach Club Resort, Broome at which Dr Ivor Roberts, Executive Director - Mineral Titles Division, Department of Mines and Petroleum, spoke next on 'Government initiatives and mineral project approvals in the Kimberley', in which according to Mr Roberts, data from the Federal Government indicated that four billion had been expended last year on exploration, and 1 ask - (1) Does form five expenditure support this figure? (2) If yes to (1), what were the expenditure figures for 201O? (3) Ifno to (1), why not? (4) What were the expenditure figures for 2010? (5) Can the Minister also advise what the total amount of expenditure exemptions for 2010 was? (6) Which leaseholders sought and received expenditure exemptions for 2010? Answer (1) No. (2) Not applicable. (3) The exploration figure of four billion dollars quoted by Dr Ivor Roberts during his presentation at the Fourth Annual Kimberley Energy and Resources Development conference was for both minerals ($1.4017 billion) and petroleum ($2.4953 billion) and sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics' website at http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSST ATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/8412.0Dec%20201 O?Open Document (4) $1,600,511,395 (the combined total expenditure as reported from Form 5 submissions). (5) Yes, $130,412,112. -

Deliver Sustainable Value

Annual Report 2020 DELIVER ABN 34 008 675 018 SUSTAINABLE VALUE ABOUT ILUKA RESOURCES lluka Resources Limited (Iluka) is an international mineral With over 3,000 direct employees, the company has sands company with expertise in exploration, project operations and projects in Australia and Sierra Leone; development, mining, processing, marketing and and a globally integrated marketing network. rehabilitation. Iluka conducts international exploration activities and The company’s objective is to deliver sustainable value. is actively engaged in the rehabilitation of previous operations in the United States, Australia and Sierra With over 60 years’ industry experience, Iluka is a Leone. leading global producer of zircon and the high grade titanium dioxide feedstocks rutile and synthetic rutile. In Listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) addition, the company has an emerging position in rare and headquartered in Perth. Iluka holds a 20% stake in earth elements (rare earths). Iluka’s products are used Deterra Royalties Limited (Deterra), the largest ASX-listed in an increasing array of applications including home, resources focussed royalty company. workplace, medical, lifestyle and industrial uses. PRODUCTS TITANIUM DIOXIDE ZIRCON TiO2 Zr Iluka is the largest producer of natural Iluka is a leading global producer of rutile and a major producer of synthetic zircon. Zircon is opaque; and heat, water, rutile, which is an upgraded, value added chemical and abrasion resistant. Primary form of ilmenite. Collectively, these uses include ceramics; refractory and products are referred to as high-grade foundry applications; and zirconium titanium dioxide feedstocks, owing to chemicals. their high titanium content. Primary uses include pigment (paints), titanium metal and welding. -

Stoxx® Australia 150 Index

STOXX® AUSTRALIA 150 INDEX Components1 Company Supersector Country Weight (%) Commonwealth Bank of Australia Banks Australia 8.37 CSL Ltd. Health Care Australia 7.46 BHP GROUP LTD. Basic Resources Australia 7.23 National Australia Bank Ltd. Banks Australia 4.37 Westpac Banking Corp. Banks Australia 4.09 Australia & New Zealand Bankin Banks Australia 3.75 Wesfarmers Ltd. Retail Australia 3.30 WOOLWORTHS GROUP Personal Care, Drug & Grocery Australia 2.87 Macquarie Group Ltd. Financial Services Australia 2.84 Rio Tinto Ltd. Basic Resources Australia 2.48 Fortescue Metals Group Ltd. Basic Resources Australia 2.27 Transurban Group Industrial Goods & Services Australia 2.20 Telstra Corp. Ltd. Telecommunications Australia 2.05 Goodman Group Real Estate Australia 1.77 AFTERPAY Industrial Goods & Services Australia 1.54 Coles Group Personal Care, Drug & Grocery Australia 1.39 Woodside Petroleum Ltd. Energy Australia 1.28 Newcrest Mining Ltd. Basic Resources Australia 1.27 Aristocrat Leisure Ltd. Travel & Leisure Australia 1.11 XERO Technology Australia 1.00 SYDNEY AIRPORT Industrial Goods & Services Australia 0.93 Brambles Ltd. Industrial Goods & Services Australia 0.91 Sonic Healthcare Ltd. Health Care Australia 0.90 ASX Ltd. Financial Services Australia 0.82 SCENTRE GROUP Real Estate Australia 0.80 Cochlear Ltd. Health Care Australia 0.74 QBE Insurance Group Ltd. Insurance Australia 0.73 SUNCORP GROUP LTD. Insurance Australia 0.71 South32 Australia Basic Resources Australia 0.71 Santos Ltd. Energy Australia 0.68 Ramsay Health Care Ltd. Health Care Australia 0.66 Insurance Australia Group Ltd. Insurance Australia 0.65 Mirvac Group Real Estate Australia 0.60 DEXUS Real Estate Australia 0.59 SEEK Ltd.