Audience Perceptions of Five Types of Radio Humor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

69 Knoxville

GM: Patrick McCurrin GSM: Patrick McCurrin Rep: Katz Net: ABC -E #149 Killeen -Temple TX PD: Patrick McCurrin CE: Steve Sullivan Dick Broadcasting Inc. (grp) 12+ Population: 243,600 Net: Focus, USA 6711 Kingston Pike, Knoxville TN 37919 % Black 19.2 (423) 588 -6511 Fax: (423) 588 -3725 % Hispanic 12.0 KRMY -AM Spanish WIVK -AM News -Talk HH Income $35,095 1050 kHz 250 w -D, ND 990 kHz 10 kw -U, DAN Total Retail (000) $1,633,007 City of license: Killeen TX City of license: Knoxville GM: Eugene Kim GSM: Stephanie Kim GSM: Jim Christenson PD: Mike Hammond PD: Marti Martinez CE: Jerry White Market Revenue (millions) Martin Broadcasting Group 1994: $4.69 314 N. 2nd St., Killeen TX 76541 WJBZ-FM Religion 1995: $4.98 (817) 628-7070 Fax: (817) 628 -7071 96.3 mHz 1.19 kw, 479' 1 996: $5.31 City of license: Seymour TN 1997: $5.56 #69 Knoxville GM: Charlotte Mull GSM: Charlotte Mull 1998: $5.92 12+ PD: Charlotte Mull CE: Milton Jones estimates provided by Radio Population: 547,400 Black 5.9 Seymour Communications Research Development Inc. % Hispanic 0.5 Box 2526, Knoxville TN 37901 HH Income $37,822 7101 Chapman Hwy.; 37920 Station Cross- Reference Total Retail (000) $6,251,017 (423) 577 -4885 Fax: On Request KITZ -FM - KOOV -FM KKIK -FM - KRMY -AM - KLFX-FM KITZ -FM KTEM -AM KKIK -FM Market Revenue (millions) Duopoly KLTX -FM KITZ -FM KTON -AM KOOV -FM 1994: $20.11 KOOC -FM KOOV -FM 1995: $21.72 WJXB -FM AC 1996: $23.46 97.5 mHz 100 kw, 1,295' 1997: $25.06 City of license: Knoxville Duopoly 1998: $27.07 GM: Craig Jacobus GSM: Jim Ridings KIIZ -FM Urban estimates provided by Radio PD: Jeff Jarnigan CE: Bob Glen 92.3 mHz 3 kw, 259' Research Development Inc. -

Industry, ASCAP Agree Him As VP /GM at the San Diego Seattle, St

ISSUE NUMBER 646 THE INDUSTRY'S WEEKLY NEWSPAPER AUGUST 1, 1986 WARSHAW NEW KFSD VP /GM I N S I D E: RADIO BUSINESS Rosenberg Elevated SECTION DEBUTS To Lotus Exec. VP This week R &R expands the Transactions page into a two -page Radio Business section. This week and in coming weeks, you'll read: Features on owners, brokers, dealmakers, and more Analyses on trends in the ever -active station acquisition field Graphs and charts summarizing transaction data Financial data on the top broadcast players And the most complete and timely news available on station transactions. Hal Rosenberg Dick Warshaw Starts this week, Page 8 KFSD/San Diego Sr. VP/GM elevated to Exec. VP for Los Hal Rosenberg has been Angeles-based parent Lotus ARBITRON RATINGS RESULTS COMPROMISE REACHED Communications, which owns The spring Arbitrons for more top 14 other stations in California. markets continue to pour in, including Texas, Arizona, Nevada, Illi- this week figures for Houston, Atlanta, nois, and Maryland. Succeeding Industry, ASCAP Agree him as VP /GM at the San Diego Seattle, St. Louis, Kansas Cincinnati, Classical station is National City, Tampa, Phoenix, Denver, Miami, Sales Manager Dick Warshaw. and more. On 7.5% Rate Hike Rosenberg, who had been at Page 24 stallments, one due by the end After remaining deadlocked KFSD since it was acquired by Increases Vary of this year, and the other. by for several years, ASCAP and Lotus in 1974, assumes his new CD OR NOT CD: By Station next April. The new rates will the All- Industry Radio Music position January 1, 1987. -

0917 Chamber.Indd

Farragut West Knox Chamber of Commerce CHAMBER “THE MISSION STATEMENT IS TO STRENGTHEN AND SUPPORT OUR COMMUNITY BY PROMOTING BUSINESS GROWTH, EDUCATIONLIFE AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT.” VOL. 31, NO. 9 A PUBLICATION OF THE FARRAGUT WEST KNOX CHAMBER OF COMMERCE SEPTEMBER 2017 Breakfast Speaker Series Panel: Knox County Sheriff’s Offi ce Chief of Administration Lee Tramel, Knox County District Attorney Gen- eral Charme Allen, Tennessee State Senator Richard Briggs, MD, Metro Drug Coalition Executive Karen Pershing pose for a group photo after wrapping up the discussion on the Opioid crisis in Tennessee. Panel Breakfast Sees 125 Attendees Over 125 registrants joined together on Fall 5K to Feature First Pack Walk Tuesday, Aug. 22 at Fox Den Country Club to Planning continues for the Chamber’s annual Fall 5K & Fun lot and arrive early to ensure plenty of time to check-in and enjoy hear important updates from the four panel Walk, now in its 23rd year, featuring its fi rst ever “pack walk” for the festivities. Watt Road closes to all traffi c at 7:30 a.m. speakers who were part of the Chamber’s any participants of the 1-mile walk who wish to bring their best The event helps fund the Chamber’s Continuing Education Breakfast Speaker Series: Discussion on the four-legged friend! Committee member, Kevin Human of Ricki’s Scholarships and 15% of registration fees goes to the Smoky Opioid Epidemic. The panel featured Tennes- Pet Depot is coordinating with certifi ed canine trainer and be- Mountain Service Dogs (SMSD) to aid in their mission to provide see State Senator, Dr. -

Exploring the Atom's Anti-World! White's Radio, Log 4 Am -Fm- Stations World -Wide Snort -Wave Listings

EXPLORING THE ATOM'S ANTI-WORLD! WHITE'S RADIO, LOG 4 AM -FM- STATIONS WORLD -WIDE SNORT -WAVE LISTINGS WASHINGTON TO MOSCOW WORLD WEATHER LINK! Command Receive Power Supply Transistor TRF Amplifier Stage TEST REPORTS: H. H. Scott LK -60 80 -watt Stereo Amplifier Kit Lafayette HB -600 CB /Business Band $10 AEROBAND Solid -State Tranceiver CONVERTER 4 TUNE YOUR "RANSISTOR RADIO TO AIRCRAFT, CONTROL TLWERS! www.americanradiohistory.com PACE KEEP WITH SPACE AGE! SEE MANNED MOON SHOTS, SPACE FLIGHTS, CLOSE -UP! ANAZINC SCIENCE BUYS . for FUN, STUDY or PROFIT See the Stars, Moon. Planets Close Up! SOLVE PROBLEMS! TELL FORTUNES! PLAY GAMES! 3" ASTRONOMICAL REFLECTING TELESCOPE NEW WORKING MODEL DIGITAL COMPUTER i Photographers) Adapt your camera to this Scope for ex- ACTUAL MINIATURE VERSION cellent Telephoto shots and fascinating photos of moon! OF GIANT ELECTRONIC BRAINS Fascinating new see -through model compute 60 TO 180 POWER! Famous actually solves problems, teaches computer Mt. Palomar Typel An Unusual Buyl fundamentals. Adds, subtracts, multiplies. See the Rings of Saturn, the fascinating planet shifts, complements, carries, memorizes, counts. Mars, huge craters on the Moon, phases of Venus. compares, sequences. Attractively colored, rigid Equat rial Mount with lock both axes. Alum- plastic parts easily assembled. 12" x 31/2 x inized overcoated 43/4 ". Incl. step -by -step assembly 3" diameter high -speed 32 -page instruction book diagrams. ma o raro Telescope equipped with a 60X (binary covering operation, computer language eyepiece and a mounted Barlow Lens. Optical system), programming, problems and 15 experiments. Finder Telescope included. Hardwood, portable Stock No. 70,683 -HP $5.98 Postpaid tripod. -

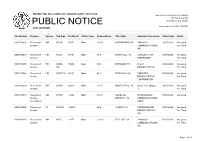

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-200720-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 07/20/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000107750 Renewal of FM WAWI 81646 Main 89.7 LAWRENCEBURG, AMERICAN FAMILY 07/16/2020 Granted License TN ASSOCIATION 0000107387 Renewal of FX W250BD 141367 97.9 LOUISVILLE, KY EDUCATIONAL 07/16/2020 Granted License MEDIA FOUNDATION 0000109653 Renewal of FX W270BK 138380 101.9 NASHVILLE, TN WYCQ, INC. 07/16/2020 Granted License 0000107099 Renewal of FM WFWR 90120 Main 91.5 ATTICA, IN FOUNTAIN WARREN 07/16/2020 Granted License COMMUNITY RADIO CORP 0000110354 Renewal of FM WBSH 3648 Main 91.1 HAGERSTOWN, IN BALL STATE 07/16/2020 Granted License UNIVERSITY 0000110769 Renewal of FX W218CR 141101 91.5 CENTRAL CITY, KY WAY MEDIA, INC. 07/16/2020 Granted License 0000109620 Renewal of FL WJJD-LP 123669 101.3 KOKOMO, IN KOKOMO SEVENTH- 07/16/2020 Granted License DAY ADVENTIST BROADCASTING COMPANY 0000107683 Renewal of FM WQSG 89248 Main 90.7 LAFAYETTE, IN AMERICAN FAMILY 07/16/2020 Granted License ASSOCIATION Page 1 of 169 REPORT NO. PN-2-200720-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 07/20/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000108212 Renewal of AM WNQM 73349 Main 1300.0 NASHVILLE, TN WNQM. -

PDF-Investor-Directory-4.14.2021.Pdf

The Knoxville Chamber thanks our Economic Investors for their commitment to driving regional economic prosperity. City of Knoxville Covenant Health Knox County Knoxville Utilities Board Pilot Company Clayton Homes, Inc. First Horizon Foundation Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority Tennessee Valley Authority Truist Bank University Health System, Inc. Denark Construction, Inc. Discovery, Inc. Home Federal Bank of Tennessee Knoxville News Sentinel ORNL Federal Credit Union Partners Development Pinnacle Financial Partners Regions Bank The University of Tennessee The Knoxville Chamber thanks its Premier Partners. Mesa Associates, Inc. ELECTRIC POWER RESEARCH Woolf, McClane, Bright, Allen & Messer Construction Company INSTITUTE (EPRI) Carpenter, PLLC Elo Touch Solutions workspace interiors, inc. ONE Business Solutions Emerson Process Management – Y-12 Federal Credit Union Phillips & Jordan, Inc. 21st Mortgage Corporation Reliability Solutions-MHM Siemens Molecular Imaging Executive Building Solutions, Inc. CMC Steel Tennessee Sitel Group First Century Bank Downtown Knoxville Alliance Summit Medical Group, PLLC Great West Casualty Company FirstBank TeamHealth Hallsdale Powell Utility District AAA Tennessee/ The Auto Club Lenoir City Utilities Board Tennova Healthcare Information Capture Solutions Group M & M Productions USA ACTS Fleet Maintenance Utilities Management Federation, Johnson & Galyon, Inc. PYA, P.C. Inc. Advent Electric KaTom Restaurant Supply, Inc. Radio Systems Corporation Verizon Communications Inc. ALLCOR Staffing Kelvion SmartBank WBIR-TV Allevia Technology Kimberly-Clark Corporation Stowers Machinery Corporation White Realty and Service Alsco Inc. Knoxville Graphic House TechMah Medical Corporation American Book Company Lewis Thomason The Trust Company of Tennessee Answer Financial, Inc Mercedes Benz of Knoxville UT-BATTELLE, LLC/ORNL Aubrey's Inc. Morning Pointe of Powell Assisted Living Avertium Accenture On Trac, Inc. -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-1-200331-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 03/31/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000109806 Renewal of AM WVJS 51071 Main 1420.0 OWENSBORO, KY HANCOCK 03/27/2020 Accepted License COMMUNICATIONS, For Filing INC. 0000109673 Renewal of FM WUOT 69161 Main 91.9 KNOXVILLE, TN UNIVERSITY OF 03/27/2020 Accepted License TENNESSEE For Filing 0000109609 Renewal of FM WJBZ- 59808 Main 96.3 SEYMOUR, TN M & M 03/26/2020 Accepted License FM BROADCASTING For Filing 0000110026 Renewal of FM WIFE-FM 54151 Main 94.3 RUSHVILLE, IN RODGERS 03/30/2020 Accepted License BROADCASTING For Filing CORPORATION 0000109939 Renewal of FM WKYM 63323 Main 101.7 MONTICELLO, KY Stephen W. Staples , 03/27/2020 Accepted License Jr. For Filing 0000109839 Renewal of AM WPWT 42652 Main 870.0 COLONIAL INFORMATION 03/30/2020 Received License HEIGHTS, TN COMMUNICATIONS Amendment CORP. 0000109902 Renewal of FX W233CI 145157 94.5 ATHENS, TN CORNERSTONE 03/27/2020 Accepted License BROADCASTING, For Filing INC. 0000109819 Renewal of AM WTCJ 18277 Main 1230.0 TELL CITY, IN HANCOCK 03/27/2020 Accepted License COMMUNICATIONS, For Filing INC. Page 1 of 21 REPORT NO. PN-1-200331-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 03/31/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. -

Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ) ) ) )

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC In the matter of: ) ) Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ) MB Docket 13-249 ) ) COMMENTS OF REC NETWORKS One of the primary goals of REC Networks (“REC”)1 is to assure a citizen’s access to the airwaves. Over the years, we have supported various aspects of non-commercial micro- broadcast efforts including Low Power FM (LPFM), proposals for a Low Power AM radio service as well as other creative concepts to use spectrum for one way communications. REC feels that as many organizations as possible should be able to enjoy spreading their message to their local community. It is our desire to see a diverse selection of voices on the dial spanning race, culture, language, sexual orientation and gender identity. This includes a mix of faith-based and secular voices. While REC lacks the technical knowledge to form an opinion on various aspects of AM broadcast engineering such as the “ratchet rule”, daytime and nighttime coverage standards and antenna efficiency, we will comment on various issues which are in the realm of citizen’s access to the airwaves and in the interests of listeners to AM broadcast band stations. REC supports a limited offering of translators to certain AM stations REC feels that there is a segment of “stand-alone” AM broadcast owners. These owners normally fall under the category of minority, women or GLBT/T2. These owners are likely to own a single AM station or a small group of AM stations and are most likely to only own stations with inferior nighttime service, such as Class-D stations. -

Inside This Issue

News DX Serving DXers since 1933 Volume 86, No. 19 ● August 23, 2019 ● (ISSN 0737-1639) Inside this issue . 2 … AM Switch 9 … Musings of the Members 12 … DX Toolbox 5 … Geomagnetic Indices 10 … Domestic DX Digest East 16 … Unreported Station List 6… Domestic DX Digest West 11 … International DX Digest 17 … GYDXA – 1490 kHz From the Board of Directors: Changes to e- years.” For more information e-mail Tim at DXN.com. [email protected] or call 414 813-7373. The National Radio Club e-DXN.com was 2019 IRCA Convention: The 2019 IRCA originally a phpBB bulletin board that over time Convention will be held on September 5, 6, and 7 required more maintenance, moderation and at the Courtyard by Marriott Seattle Southcenter, expense. We determined, and the membership 400 Andover Park West, Tukwila WA 98188. agreed, that the biggest service wanted as DX Registration is free to IRCA members, $25 to News magazine in a timely fashion without the non-members. Phone number(s) for room costs associated with the printed addition. e- reservations are 800-321-2211 or 206-575-2500. DXN.com is now a direct mailer to our You must mention International Radio Club of subscribers. These changes are effective with this America Convention to get this rate. For more issue and all e-DXN.com subscribers will be info: Mike Sanburn: [email protected]. receiving this issue’s pdf via email. Our weekly From the Publisher: Slow summer issue; look AMS and other timely updates will be for a nice big one in mid-September! distributed the same way The National Radio Club has placed all but the Membership Report most current archived DX News files on “My HQ-180AC is in mothballs, I'm thinking www.nationalradioclub.org for both our of remoting a Perseus at a friend's house out in membership and the public to enjoy. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

December 2018

The Magazine for TV and FM DXers December 2018 Photo by Nam Nguyen (Wikipedia) AUSTRALIA CHECKS IN WITH SOME TROPO REMEMBER, THIS IS THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION SEND THOSE INTERNATIONAL REPORTS IN! THIS IS RYAN'S LAST VUD AS EDITOR (BUT I'LL STILL BE AROUND) The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association INSIDE THIS VUD CLICK TO NAVIGATE 02 The Mailbox 21 FM News 33 Photo News 03 TV News 30 Southern FM DX 36 Brisbane Tropo 17 FM Facilities DX REPORTS/PICS FROM: Ryan Leigh Donaldson (QLD), Chris Dunne (FL), Fred Nordquist (SC), Doug Speheger (OK) THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, KEITH McGINNIS, JIM THOMAS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Ryan Grabow Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org/info Webmaster: Tim McVey Forum Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, John Zondlo and Mike Bugaj DECEMBER 2018 DUES RECEIVED think that day was around 15 years ago. George DATE NAME S/P EXP resides in Duxbury, MA. It’s nice to have you back 10/31/2018 Doug Speheger OK 10-19 again! Imagine how the Boston FM dial has 11/5/2018 Scott Levitt PA 10-19 changed in that time. -

Kentucky, North Carolina, and Tennessee Trip, October 16-17, 1964

Remarks of Senator Hubert H. Humphrey ~ shcvillo ~ ir p ort ~ shevillo , North Ca rolina October 17, 1964 ~onato r Hum phr e y . Th o nk you vory much. Thank you , Billy . Th ank you very, very much. My dear friends , I just ca n ' t t oll you how plea sed I a m to bo introduced on this day ho r o in As hovillo, North CArolina, by such a fino a nd good man a nd good Domocr a t a s the gentlema n that ha s just pr osontod mo, Billy We bb, a nd I wa nt to thank you vory , vory much, Bill , for your wonderful presentation . I a m happy t o bo in North Ca rolina . I ca n sao , however , tha t you must ha ve had a Rep ublica n through her o rocontly because it is sort o f windy . ( ~pp l a us o -- -~ ~~ught e r) But you f olks just s tick with us Dem ~ cr a ts a nd your good Democrats , a nd wo will ha vo th o sun shining aga in just lik o it a lwa ys docs in North Ca rolina . ( ~pp l a uso) . You kn ow, I just wont you t o know how bea utiful it is to fly ovor theso mountains a nd thoso hills a nd vollie s, t o com o horo during th o timo when thoro is th o l oa vo cha ngo, when tho colors of tho troos a n d th o l oovos make ono roa lizo if wo ovor had a ny do ubt 2bout it, that a Divino Pr ovi do nco truly contro l s our livos a nd our worl d .