Open Government Data and Value Creation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secure Smart Identity for Healthcare TAAVI EINASTE, HEAD of DIGITAL HEALTH

© Nortal Group 2017 nortal.com Secure smart identity for healthcare TAAVI EINASTE, HEAD OF DIGITAL HEALTH OCTOBER 16TH, 2017. TALLINN 2017 Group Nortal © Health care expenditure varies around the world Canada $5,718 UK $3,598 Netherlands $6,145 China $367 Germany $5,006 US $9,146 Japan $3,966 United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Mexico $664 Qatar $1,473 India $61 Brazil $1,083 Australia $5,827 2017 Group Nortal © $12 $9,146 Health expenditure per capita (current US$) Health spending has outpaced economic growth Average growth rate of health spending and GDP per capita, 1990-2012 8.0% 7.0% Health spending 6.0% matching GDPgrowth 5.0% 4.0% 3.0% 2.0% 2017 0.0% ITA ISL FIN ISR IRL Group DEU LUX CHE CAN DNK SWE GRC HUN FRA ESP AUT MEX USA BEL AUS JPN NZL NLD NGR GBR SVN CZE PRT EST POL CHL TUR SVK KOR Nortal © GDP growth per capita Health spending growth per capita © Nortal Group And we know is possible we know And for What wehope Paulina had been feeling bad for a long time and opened eHealth inside Apple’s Health app to book an appointment with her healthcare provider. Group Nortal © eHealth’s AI asked Pauliina some questions recommended she meet her family doctor. It sent an appointment request to Dr. Martin, adding the questionnaire results. Group Nortal © Dr. Martin received the request and agreed to meet Paulina. AI saw a conflict in their merged calendars and suggested Paulina met Dr. Miller instead. Group Nortal © Paulina met Dr. -

CS TETRIS 205X266+Bleed3 Copy.Indd

CASE STUDY HELPING PEOPLE WITH REDUCED WORK ABILITY RETURN TO THE LABOR MARKET ESTONIA FINLAND GERMANY SWEDEN US OMAN UAE LITHUANIA SERBIA EASE OF DOING BUSINESS TETRIS is an information system commissioned by the Estonian Unemployment Insurance Fund for the purpose of performing fair and accurate work ability assessments and granting disability benefits in accordance with legal and procedural requirements. The Work Ability Reform of 2016 obligated the Fund to take over the bulk of work ability assessment and work ability benefit provision from the Social Insurance Board. With over 100,000 potential clients and tight deadlines, the reform’s success depended on optimized business processes and a versatile information system, which Nortal delivered. The Challenge In 2016, Estonia intended to introduce an extensive work ability reform, which would affect more than 100,000 people receiving disability benefits. The reform set out to achieve four major goals: Foster a more positive attitude in society towards Handle all of the people currently receiving 1 people with reduced work ability, which would 2 disability benefits on an individual basis and also have a positive effect on their self-image. determine their actual eligibility. Help people with reduced work ability to return Increase tax revenue and reduce costs on a 3 to the labor market. 4 national level. What made the task even more challenging was the legal obligation to assess an applicant’s work ability within 30 days and pay the benefits by the 10th of each month. Any delays here would impair the quality of life of the applicant, not to mention the related overdue charges the Fund would have to incur. -

Egovernance WP-A4+Bleed3

nortal.com WHITE PAPER Why build a digital government E-GOVERNANCE Governments globally are facing a huge challenge — exponentially, people are expecting interactions with the state to move from paper to online; citizens are also expecting governments to treat them as valued customers. Not many countries have mastered the transition from paper to a digital, seamless society successfully. Estonia is an exception. Being true digital governance trailblazers, Estonians can help other governments achieve the same. WHY BUILD A DIGITAL GOVERNMENT For a country to succeed, it has to go digital Millennials and Generation Z are taking over. And this does not apply only to younger Constituting half of the world’s population, they generations. People of all age groups are stay in designer hostels when on business trips, increasingly accustomed to shopping with a click, UEQNFVJGPKPGVQƒXGYQTMKPICTTCPIGOGPVCPF ordering a taxi from an app or assuming they constantly search for meaning in their work. should be able to interact with their governments They also love paper notebooks, but not so much online. In Estonia, where people have been able to VJGRCRGTYQTMVJG[PGGFVQƒNNQWVKPQTFGTVQ vote online in national elections since 2005, the communicate with their governments. oldest voters have been more than 100 years old. Glued to their screens, they expect to interact For governments, keeping up with these new with service providers virtually, from wherever expectations is a challenge. It’s a huge change in they are. More and more, people are applying the mindset for governments — how to make life easier same expectations to governments. Younger for people so they’ll be happier citizens and to generations see governments as service providers, also attract talent from other countries to relocate and they believe interaction with their governments there? should be as easy and smooth as buying a pair of headphones online. -

Have a Mobile Phone

102724 A World Bank Group Flagship Report DIGITAL DIVIDENDS Digital technologies are spreading rapidly, but digital dividends— world development report the broader benefits of faster growth, more jobs, and better services—are not. If more than 40 percent of adults in East Africa Public Disclosure Authorized pay their utility bills using a mobile phone, why can’t others around the world do the same? If 8 million entrepreneurs in China—one-third of them women—can use an e-commerce platform to export goods to 120 countries, why can’t entrepreneurs elsewhere achieve the same global reach? And if India can provide unique digital identifica- tion to 1 billion people in five years, and thereby reduce corruption by billions of dollars, why can’t other countries replicate its success? Indeed, what’s holding back countries from realizing the profound and transformational effects that digital technologies are supposed to deliver? Two main reasons. First, nearly 60 percent of the world’s population are still offline and can’t participate in the digital economy in any meaningful way. Second, and more important, Public Disclosure Authorized the benefits of digital technologies can be offset by growing risks. DIGITAL Startups can disrupt incumbents, but not when vested interests and regulatory uncertainty obstruct competition and the entry of new firms. Employment opportunities may be greater, but not when DIVIDENDS the labor market is polarized. The internet can be a platform for universal empowerment, but not when it becomes a tool for state OVERVIEW control and elite capture. The World Development Report 2016 shows that while the digital revolution has forged ahead, its “analog complements”—the regulations that promote entry and competition, the skills that enable workers to access and then leverage the new economy, and the institutions that are accountable to citizens—have not kept Public Disclosure Authorized pace. -

Start a Business in 2 Minutes

nortal.com WHITE PAPER Start a business in 2 minutes EASE OF DOING BUSINESS The days when starting a business took months and involved a lot of red tape are over. With the help of strategic thinking and technology, the time to register a company can take far less time than boiling an egg. This white paper shows how this can be done. “Every responsible government has the mission to build and maintain a thriving business climate in order to maximize wealth for society.” Rein Lang, Estonian ex. Minister of Justice The Seamless Society Where government, businesses and individuals meet How to do this? First, by approaching the mission from the investor’s perspective. Investor expects the communication with the government institutions to be transparent, secure and fast. And all this is possible today. Nortal Estonia used to hold the world record for registering a new Nortal helps governments to company in 18 minutes. In 2015, a new record has been set by improve local business climate Oman, where the fastest new company registration was via reforms powered by completed in only 1 minute and 6 seconds. technology. We call them Nordic talent (Nortal) solutions. Both records became possible thanks to Nortal’s expertise in building a seamless e-government. Ease of doing business 03 Setting trends for the world Starting a business Nortal Vision What affects the ease of starting a business: “Every responsible government has the mission to build Investments flow in and and maintain a thriving business climate in order to 1. Number of procedures economic activity speeds up, 2. -

Dataradar: Data Governance Has Never Been Easier

nortal.com CASE STUDY DataRadar: data governance has never been easier DATA PROTECTION A comprehensive new tool for data governance, DataRadar provides an overview of the data an organization has and creates a fully fact-based data map. DEEPSCAN: DATA GOVERNANCE HAS NEVER BEEN EASIER Data is the new oil. How wealthy are you? DataRadar helps you find out. Are you ready for the GDPR? The EU’s new General Compliance is not optional, so why not make it Data Protection Regulation applies to all businesses work for you? DataRadar lets you take control whose customers are EU residents. The GDPR is an of your data, turning compliance costs into an opportunity to understand the value of the data your investment that generates an actual return. Treat organization collects and stores. DataRadar is a the GDPR as an opportunity to use data for smarter data governance tool that converts your compliance sales and marketing, creating seamless customer costs into an investment that can deliver a real experiences. return. We believe GDPR will not be the end of the data- driven customer journey. Instead, it is a great opportunity to turn your compliance costs into investments in new business models. Priit Alamäe, Nortal's CEO Benefits Simpler business Better data quality Data is protected processes Superior data quality facilitates Quality data gives your company Proper data governance mitigates better decision making and a competitive advantage. A full data- and privacy-related risks relat- simplifies business processes – overview of your data improves its ed to data breaches and the danger enabling insights into customers’ quality and reliability across your of public shaming for customer natural data patterns as well as entire organization. -

Changing Economy Changing Society

CHANGING ECONOMY CHANGING SOCIETY IT INDUSTRY IN POST-SOVIET COUNTRIES ANATOLY MOTKIN CHANGING ECONOMY CHANGING SOCIETY IT INDUSTRY IN POST-SOVIET COUNTRIES ANATOLY MOTKIN ABOUT STRATEGEAST StrategEast is a strategic center whose goal is to create closer working ties between political and business leaders in the former Soviet countries outside of Russia and their peers in the United States and Western Europe. StrategEast believes nations from the former Soviet Union share a heritage that has resulted in common obstacles to the formation of stable, efficient, market-oriented democracies. We hope to appeal to political, business and, academic leaders in post-Soviet countries and the West, helping them better understand one another, communicate across borders, and collaborate to support real change. Our work is focused on the 14 former Soviet states outside of Russia. This post-Soviet, non-Russia (PSNR) region includes: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. StrategEast focuses on six key issue areas that are especially influential to the transition to Western political and economic systems: fighting corruption, implementing a Western code of business conduct within a post-Soviet business environment, modernizing infrastructure; promoting independent press and civil society, energy transparency, LEARN MORE AT OUR WEBSITE: and leadership impact. www.StrategEast.org StrategEast is a registered 501c3 based in the United States. StrategEast focused on the Former Soviet Union outside PSNR© – of the Russian Federation. StrategEast sees Post-Soviet Non- Russian (PSNR©) nations as coalescing around and facing Post-Soviet common geopolitical challenges. We are strongly convinced Non-Russian that the rapprochement of the post-Soviet elites with American and West European government institutions and civil society serves the interests of global security and could gradually lead to the Westernization of the entire region. -

Lithuania: Better Care Through National Health Record

CASE STUDY LITHUANIA: BETTER CARE THROUGH NATIONAL HEALTH RECORD ESTONIA FINLAND GERMANY US OMAN UAE LITHUANIA SERBIA DIGITAL HEALTHCARE Lithuania’s health records system was in desperate need of modernization. Patient files were kept on paper and hospitals had their own procedures for keeping records. Thanks to Nortal, Lithuania now has a fully functional national health record that saves time and a range of other resources. Smarter healthcare through digitization Gabija was visiting the capital when her asthma took a frightening turn for the worse. Despite being far from her home clinic, doctors were able to instantly access Gabija’s medical history and treat her immediately. A few years ago, the records retrieval would have taken days. Luckily, Nortal has created a centralized, national health record system (NHR) for Lithuania (ESPBI IS), which is fundamentally transforming the nation’s healthcare landscape. SERVICE SOLUTION DESIGN OFFER STRATEGY ADOPTION INTRODUCTING USER MANAGEMENT NHR TO DOCTORS TRAINING CHANGE SOLUTION ARCHITECTURE, DEVELOPMENT & SUPPORT TECHNOLOGY Nortal’s steps in the NHR project LITHUANIA: BETTER CARE THROUGH NATIONAL HEALTH RECORD The Challenge Lithuania’s health records system was in desperate medical files, or their children’s. The task was at best need of modernization. Not only were patient files burdensome, if not outright impossible. primarly kept on paper, each hospital maintained them separately using its own record-keeping procedures. The outdated setup was also creating problems at the highest levels. In the absence of digitization, state Predictably, such a disjointed system led to multiple policymakers had no way of performing analytics that information bottlenecks. Doctors from one institution would give them an accurate picture of the nation’s had to wait several days to retrieve records from health needs, nor did they have any hope of adding another. -

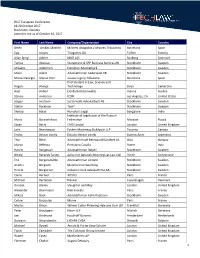

Countryname Company Jobtitle Austria AUVA Dr. Belgium AAL

CountryName Company JobTitle Austria AUVA Dr. Belgium AAL Association Communication Officer Belgium AAL Programme Communication Officer Belgium AAL Programme Director Belgium AGE Platform Europe Secretary General Belgium Agfa HealthCare N.V. President EMEA Belgium Application Developers Allianc policy manager, Europe Belgium Carestream Health Business Development Manager Belgium DIGITALEUROPE Policy Director Belgium EESC Dr. Belgium EHTEL Secretary General Belgium EHTEL eHealth expert Belgium ESIP- Health Insurance Health Policy Advisor Belgium European Commission Head of Unit Belgium Eurorec Vice President Research Belgium EuroRec Institute Medical Director Belgium HL7 Foundation Secretary General Belgium iMinds Program manager Belgium International Diabetes Federat CEO Belgium Medinternals Enterprise Architect Belgium RAMIT VZW Director Belgium State University Ghent Head of Dept of Health Info Belgium Université libre de Bruxelles Project leader Belgium UZ Brussel Application Manager CWS Bulgaria Security Solutions Institute CEO Bulgaria Security Solutions Institute Business Development Associate Croatia APIS IT d.o.o. Business Analyst Croatia APIS IT d.o.o. Business Architect Croatia Croatian Health Insurance Fund Head of Division Croatia Croatian Health Insurance Fund Deputy Director for ICT Croatia Croatian Health Insurance Fund Director Cyprus University of Cyprus Professor Czech Republic UK 1. LF docent Czech Republic VZP Cr CIO VZP CR Denmark IHTSDO Customer Relations Lead EMEA Denmark IHTSDO Chairman Denmark Mental Health Southern -

Estonia's Digital Transformation: Mission Mystique and the Hiding Hand

Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose Estonia’s digital transformation: Mission mystique and the hiding hand Rainer Kattel Professor of Innovation and Public Governance Deputy Director, UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose Ines Mergel Professor of Public Administration, University of Konstanz, Department of Politics and Administration Working Paper IIPP WP 2018-09 September 2018 About the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose The UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (IIPP) aims to develop a new framework for creating, nurturing and evaluating public value in order to achieve economic growth that is more innovation-led, inclusive and sustainable. We intend this framework to inform the debate about the direction of economic growth and the use of mission-oriented policies to confront social and technological problems. Our work will feed into innovation and industrial policy, financial reform, institutional change, and sustainable development. A key pillar of IIPP's research is its understanding of markets as outcomes of the interactions between different actors. In this context, public policy should not be seen as simply fixing market failures but also as actively shaping and co-creating markets. Re-focusing and designing public organisations around mission-led, public purpose aims will help tackle the grand challenges facing the 21st century. IIPP is housed in The Bartlett, a leading Global Faculty of the Built Environment at UCL, with its radical thinking about space, design and sustainability. Suggested citation Kattel, R. and Mergel, I. (2018). Estonia’s digital transformation: Mission mystique and the hiding hand. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2018-09). -

Attendee List As of October 10, 2017

2017 European Conference 18-20 October 2017 Stockholm, Sweden Attendee List as of October 10, 2017 First Name Last Name Company/Organization City Country Belén Arribas Sánchez Miliners Abogados y Aesores Tributarios Barcelona Spain Epp Aasaru Triogames OÜ Tallinn Estonia Allan Bjerg Adeler NNIT A/S Soeborg Denmark Tomas Akesson Storebrand & SPP Business Services AB Stockholm Sweden Mikaela Alderhorn Hamilton Advokatbyrå Stockholm Sweden Malin Allard Advokatfirman Cederquist KB Stockholm Sweden Manuel Giorgio Alonso Porri Jausas Legal y Tributario Barcelona Spain PhD Student in Law, Science and Rogers Alunge Technology Buea Cameroon Axel Anderl Dorda Rechtsanwälte Vienna Austria Steven Andersen ICDR Los Angeles, CA United States Jörgen Axelsson Setterwalls Advokatbyrå AB Stockholm Sweden Stefan Backman Tele2 Stockholm Sweden Sharda Balaji NovoJuris Legal Bangalore India Institute of Legislation of the Russian Maria Baranchikova Federation Moscow Russia Susan Barty CMS London London United Kingdom John Beardwood Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP Toronto Canada Emilio Beccar Varela Estudio Beccar Varela Buenos Aires Argentina Thor Beke Advokatfirmaet Berngaard/Sandbek AS Oslo Norway Marco Bellezza Portolano Cavallo Rome Italy Henrik Bengtsson Advokatfirman Delphi Stockholm Sweden Nicole Beranek Zanon de la cruz beranek Attorneys-at-Law Ltd. Zürich Switzerland Erik Bergenstråhle Advokatfirman Lindahl Stockholm Sweden Anders Bergsten Mannheimer Swartling Stockholm Sweden Henrik Bergstrom Osborne Clark Advokatfirma AB Stockholm Sweden Claire Bernier -

Estonian ICT Cluster the Estonian ICT Cluster Is the Gateway to Estonian ICT Competence

Estonian ICT Cluster The Estonian ICT Cluster is the gateway to Estonian ICT competence. Our partners are experienced in implementing ideas according to the needs of a specific field, or even an entire country. The following pages provide a brief introduction to the companies behind of the e-Estonia success story. European Union Investing European Regional in your future Development Fund estonia.ee e-estoniax.com all over the 128 world countries yes, there are some in here as well Estonian ICT cluster – your gateway to References the e-Estonia • Invest Easy in Oman – the country of Oman jumped 127 places in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business index after going live with our “Invest Easy” web-portal. powerhouse Improving client satisfaction – your web store or We help countries and organizations achieve e-service functions seamlessly and logically. world-class digital societies. • E-system for federal budget management in Nigeria Our ability to simultaneously improve policy, organiza- We built a system for the government of Nigeria to tional processes, and technology sets us apart. manage their federal budget and human resources, saving the government 2.5 billion USD in 2014 alone- Estonian IT companies operate on a one-stop shop logic, saving money – before an extensive web development offering strategy consulting, change we create a prototype that helps find the solution’s management, and IT development for creating weaknesses. working e-solutions. • Efficient e-Governance in Estonia Seamlessly working digital services increase Estonia is a foremost digital society. All services in our the potential for economic growth and a higher country are just a click away – voting for your repre- sentatives in parliament or signing contracts with your quality of life.