Marine Environment & Ecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.PDF

Version: 1.7.2015 South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 An Act to provide for the establishment and management of reserves for public benefit and enjoyment; to provide for the conservation of wildlife in a natural environment; and for other purposes. Contents Part 1—Preliminary 1 Short title 5 Interpretation Part 2—Administration Division 1—General administrative powers 6 Constitution of Minister as a corporation sole 9 Power of acquisition 10 Research and investigations 11 Wildlife Conservation Fund 12 Delegation 13 Information to be included in annual report 14 Minister not to administer this Act Division 2—The Parks and Wilderness Council 15 Establishment and membership of Council 16 Terms and conditions of membership 17 Remuneration 18 Vacancies or defects in appointment of members 19 Direction and control of Minister 19A Proceedings of Council 19B Conflict of interest under Public Sector (Honesty and Accountability) Act 19C Functions of Council 19D Annual report Division 3—Appointment and powers of wardens 20 Appointment of wardens 21 Assistance to warden 22 Powers of wardens 23 Forfeiture 24 Hindering of wardens etc 24A Offences by wardens etc 25 Power of arrest 26 False representation [3.7.2015] This version is not published under the Legislation Revision and Publication Act 2002 1 National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972—1.7.2015 Contents Part 3—Reserves and sanctuaries Division 1—National parks 27 Constitution of national parks by statute 28 Constitution of national parks by proclamation 28A Certain co-managed national -

Habitat Types

Habitat Types The following section features ten predominant habitat types on the West Coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. It provides a description of each habitat type and the native plant and fauna species that commonly occur there. The fauna species lists in this section are not limited to the species included in this publication and include other coastal fauna species. Fauna species included in this publication are printed in bold. Information is also provided on specific threats and reference sites for each habitat type. The habitat types presented are generally either characteristic of high-energy exposed coastline or low-energy sheltered coastline. Open sandy beaches, non-vegetated dunefields, coastal cliffs and cliff tops are all typically found along high energy, exposed coastline, while mangroves, sand flats and saltmarsh/samphire are characteristic of low energy, sheltered coastline. Habitat Types Coastal Dune Shrublands NATURAL DISTRIBUTION shrublands of larger vegetation occur on more stable dunes and Found throughout the coastal environment, from low beachfront cliff-top dunes with deep stable sand. Most large dune shrublands locations to elevated clifftops, wherever sand can accumulate. will be composed of a mosaic of transitional vegetation patches ranging from bare sand to dense shrub cover. DESCRIPTION This habitat type is associated with sandy coastal dunes occurring The understory generally consists of moderate to high diversity of along exposed and sometimes more sheltered coastline. Dunes are low shrubs, sedges and groundcovers. Understory diversity is often created by the deposition of dry sand particles from the beach by driven by the position and aspect of the dune slope. -

Place Names of South Australia: W

W Some of our names have apparently been given to the places by drunken bushmen andfrom our scrupulosity in interfering with the liberty of the subject, an inflection of no light character has to be borne by those who come after them. SheaoakLog ispassable... as it has an interesting historical association connectedwith it. But what shall we say for Skillogolee Creek? Are we ever to be reminded of thin gruel days at Dotheboy’s Hall or the parish poor house. (Register, 7 October 1861, page 3c) Wabricoola - A property North -East of Black Rock; see pastoral lease no. 1634. Waddikee - A town, 32 km South-West of Kimba, proclaimed on 14 July 1927, took its name from the adjacent well and rock called wadiki where J.C. Darke was killed by Aborigines on 24 October 1844. Waddikee School opened in 1942 and closed in 1945. Aboriginal for ‘wattle’. ( See Darke Peak, Pugatharri & Koongawa, Hundred of) Waddington Bluff - On section 98, Hundred of Waroonee, probably recalls James Waddington, described as an ‘overseer of Waukaringa’. Wadella - A school near Tumby Bay in the Hundred of Hutchison opened on 1 July 1914 by Jessie Ormiston; it closed in 1926. Wadjalawi - A tea tree swamp in the Hundred of Coonarie, west of Point Davenport; an Aboriginal word meaning ‘bull ant water’. Wadmore - G.W. Goyder named Wadmore Hill, near Lyndhurst, after George Wadmore, a survey employee who was born in Plymouth, England, arrived in the John Woodall in 1849 and died at Woodside on 7 August 1918. W.R. Wadmore, Mayor of Campbelltown, was honoured in 1972 when his name was given to Wadmore Park in Maryvale Road, Campbelltown. -

Musgrave Subregional Description

Musgrave Subregional Description Landscape Plan for Eyre Peninsula - Appendix D The Musgrave subregion extends from Mount Camel Beach in the north inland to the Tod Highway, and then south to Lock and then west across to Lake Hamilton in the south. It includes the Southern Ocean including the Investigator Group, Flinders Island and Pearson Isles. QUICK STATS Population: Approximately 1,050 Major towns (population): Elliston (300), Lock (340) Traditional Owners: Nauo and Wirangu nations Local Governments: District Council of Elliston, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula and Wudinna District Council Land Area: Approximately 5,600 square kilometres Main land uses (% of land area): Grazing (30% of total land area), conservation (20% of land area), cropping (18% of land area) Main industries: Agriculture, health care, education Annual Rainfall: 380 - 430mm Highest Elevation: Mount Wedge (249 metres AHD) Coastline length: 130 kilometres (excludes islands) Number of Islands: 12 2 Musgrave Subregional Description Musgrave What’s valued in Musgrave Pearson Island is a spectacular The landscapes and natural resources of the Musgrave unspoilt island with abundant and subregion are integral to the community’s livelihoods and curious wildlife. lifestyles. The Musgrave subregion values landscapes include large The coast is enjoyed by locals and visitors for its beautiful patches of remnant bush and big farms. Native vegetation landscapes, open space and clean environment. Many is valued by many in the farming community and many local residents particularly value the solitude, remoteness recognise its contribution to ecosystem services, and and scenic beauty of places including Sheringa Beach, that it provides habitat for birds and reptiles. -

Conserving Marine Biodiversity in South Australia - Part 1 - Background, Status and Review of Approach to Marine Biodiversity Conservation in South Australia

Conserving Marine Biodiversity in South Australia - Part 1 - Background, Status and Review of Approach to Marine Biodiversity Conservation in South Australia K S Edyvane May 1999 ISBN 0 7308 5237 7 No 38 The recommendations given in this publication are based on the best available information at the time of writing. The South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) makes no warranty of any kind expressed or implied concerning the use of technology mentioned in this publication. © SARDI. This work is copyright. Apart of any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the publisher. SARDI is a group of the Department of Primary Industries and Resources CONTENTS – PART ONE PAGE CONTENTS NUMBER INTRODUCTION 1. Introduction…………………………………..…………………………………………………………1 1.1 The ‘Unique South’ – Southern Australia’s Temperate Marine Biota…………………………….…….1 1.2 1.2 The Status of Marine Protected Areas in Southern Australia………………………………….4 2 South Australia’s Marine Ecosystems and Biodiversity……………………………………………..9 2.1 Oceans, Gulfs and Estuaries – South Australia’s Oceanographic Environments……………………….9 2.1.1 Productivity…………………………………………………………………………………….9 2.1.2 Estuaries………………………………………………………………………………………..9 2.2 Rocky Cliffs and Gulfs, to Mangrove Shores -South Australia’s Coastal Environments………………………………………………………………13 2.2.1 Offshore Islands………………………………………………………………………………14 2.2.2 Gulf Ecosystems………………………………………………………………………………14 2.2.3 Northern Spencer Gulf………………………………………………………………………...14 -

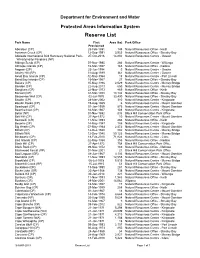

Reserve List

Department for Environment and Water Protected Areas Information System Reserve List Park Name First Area (ha) Park Office Proclaimed Aberdour (CP) 28-Feb-1991 145 Natural Resources Office - Keith Acraman Creek (CP) 12-Sep-1991 3,953 Natural Resources Office - Streaky Bay Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary National Park- 27-Oct-2016 14,802 Natural Resources Centre - Gawler Winaityinaityi Pangkara (NP) Aldinga Scrub (CP) 07-Nov-1985 266 Natural Resources Centre - Willunga Althorpe Islands (CP) 16-Mar-1967 163 Natural Resources Office - Kadina Angove (CP) 23-Jun-1994 5 Natural Resources Centre - Gawler Anstey Hill (RP) 31-Aug-1989 361 Natural Resources Centre - Gawler Avoid Bay Islands (CP) 02-May-1968 18 Natural Resources Centre - Port Lincoln Baird Bay Islands (CP) 16-Mar-1967 27 Natural Resources Office - Streaky Bay Bakara (CP) 15-May-1986 2,029 Natural Resources Centre - Murray Bridge Bandon (CP) 22-Aug-2013 650 Natural Resources Centre - Murray Bridge Bangham (CP) 22-Nov-1973 869 Natural Resources Office - Keith Barwell (CP) 31-Mar-1988 10,142 Natural Resources Office - Streaky Bay Bascombe Well (CP) 02-Jul-1970 33,430 Natural Resources Office - Streaky Bay Baudin (CP) 28-Mar-2002 310 Natural Resources Centre - Kingscote Baudin Rocks (CP) 19-Aug-1965 6 Natural Resources Centre - Mount Gambier Beachport (CP) 01-Jan-1959 875 Natural Resources Centre - Mount Gambier Beatrice Islet (CP) 16-Mar-1967 103 Natural Resources Centre - Kingscote Belair (NP) 01-Nov-1892 835 Black Hill Conservation Park Office Belt Hill (CP) 27-Apr-1972 10 -

Green Tips at Home

Green Tips At Home What we do in our everyday lives has an impact on biodiversity. We can all make a difference at home by planting a garden to attract wildlife, reducing our ecological footprint (or impact on the earth), and following these green tips. Gardening for biodiversity Create a backyard for wildlife by planting local native species that attract native butterflies, birds and other animals to your garden. Choose garden plants wisely and avoid planting species that are known to become weeds. A plant from your garden can become a serious problem for our natural environment if it escapes into the wild. Dispose of garden waste carefully. Weeds, prunings and grass clippings dumped in the bush can introduce or spread weeds. Use pesticides and herbicides sparingly. If you must use pesticides in the garden, think about using those made from natural ingredients, such as pyrethrum. Birds, frogs and reptiles can become sick or die if they feed on insects sprayed with pesticides. Use fertilisers sparingly. Chemical fertilisers increase nutrient runoff, which causes excessive algae growth in our waterways and the marine environment. In bushland, high nutrient water and runoff encourages weeds, which smother native vegetation. Protecting wildlife Leave wood for wildlife. Consider alternatives, such as gas, for heating your home. If using firewood, obtain it from reputable wood merchants, not native bushland. Keep your cats inside at night, put bells on their collar and have them desexed. Native animals do most of their feeding at night and can easily become extra food for pets. Volunteer and learn how to be a wildlife carer. -

Terrestrial and Marine Protected Areas in Australia

TERRESTRIAL AND MARINE PROTECTED AREAS IN AUSTRALIA 2002 SUMMARY STATISTICS FROM THE COLLABORATIVE AUSTRALIAN PROTECTED AREAS DATABASE (CAPAD) Department of the Environment and Heritage, 2003 Published by: Department of the Environment and Heritage, Canberra. Citation: Environment Australia, 2003. Terrestrial and Marine Protected Areas in Australia: 2002 Summary Statistics from the Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database (CAPAD), The Department of Environment and Heritage, Canberra. This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Assistant Secretary Parks Australia South Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601. The views and opinions expressed in this document are not necessarily those of the Commonwealth of Australia, the Minister for Environment and Heritage, or the Director of National Parks. Copies of this publication are available from: National Reserve System National Reserve System Section Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 or online at http://www.deh.gov.au/parks/nrs/capad/index.html For further information: Phone: (02) 6274 1111 Acknowledgments: The editors would like to thank all those officers from State, Territory and Commonwealth agencies who assisted to help compile and action our requests for information and help. This assistance is highly appreciated and without it and the cooperation and help of policy, program and GIS staff from all agencies this publication would not have been possible. An additional huge thank you to Jason Passioura (ERIN, Department of the Environment and Heritage) for his assistance through the whole compilation process. -

Status and Trends in Abundance of New Zealand Fur Seal Populations in South Australia

Status and trends in abundance of New Zealand fur seal populations in South Australia Peter D Shaughnessy, Simon D Goldsworthy and Alice I Mackay SARDI Publication No. F2014/000338-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 781 SARDI Aquatics Sciences PO Box 120 Henley Beach SA 5022 June 2014 Final Report to the Australian Marine Mammal Centre Status and trends in abundance of New Zealand fur seal populations in South Australia Final report to the Australian Marine Mammal Centre Peter D Shaughnessy, Simon D Goldsworthy and Alice I Mackay SARDI Publication No. F2014/000338-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 781 June 2014 This publication may be cited as: Shaughnessy, P. D. 1,2, Goldsworthy, S. D. 1, and Mackay, A. I. 1 (2014). Status and trends in abundance of New Zealand fur seal populations in South Australia. Final report to the Australian Marine Mammal Centre. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2014/000338-1. SARDI Research Report Series No. 781. 33pp. Cover Photo: Simon D. Goldsworthy 1SARDI Aquatic Sciences, PO Box 120, Henley Beach, SA 5022 2 South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5000 South Australian Research and Development Institute SARDI Aquatic Sciences 2 Hamra Avenue West Beach SA 5024 Telephone: (08) 8207 5400 Facsimile: (08) 8207 5406 http://www.sardi.sa.gov.au DISCLAIMER The authors warrant that they have taken all reasonable care in producing this report. The report has been through the SARDI internal review process, and has been formally approved for release by the Research Chief, Aquatic Sciences. Although all reasonable efforts have been made to ensure quality, SARDI does not warrant that the information in this report is free from errors or omissions. -

Land-Birds of Three Islands Off the West Coast of Eyre Peninsula, South Australia: Lilliput, Nicolas Baudin and West Waldegrave

Corella, 2008, 32(1): 17-19 LAND-BIRDS OF THREE ISLANDS OFF THE WEST COAST OF EYRE PENINSULA, SOUTH AUSTRALIA: LILLIPUT, NICOLAS BAUDIN AND WEST WALDEGRAVE PETER SHAUGHNESSY1, TERRY DENNIS2, DAVE ARMSTRONG3 and STEVE BERRIS4 1South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000 Email: [email protected] 25 Bell Court, Encounter Bay, South Australia 5211 3Venus Bay Conservation Park, c/o PO, Port Kenny, South Australia 5671 4RSD 107, Kingscote, South Australia 5223 Received: 17 May 2007 INTRODUCTION Nitre bushes (Nitraria billardierei), African Boxthorn bushes (Lycium ferocissimum) and many smaller plant species. There This note provides information on land-birds of three small are small caves and overhangs among limestone cliffs islands off the west coast of Eyre Peninsula: Lilliput Island near immediately inland of the granite boulders. The island is part Smoky Bay, Nicolas Baudin Island near Sceale Bay and West of the Waldegrave Islands Conservation Park. Waldegrave Island near Elliston. These islands have important colonies of the Australian Sea-lion Neophoca cinerea and were Access to each island was by rigid inflatable dinghy, visited primarily to monitor breeding activity and outcomes for launched from a larger vessel used for the 30–60 minute open that species. Information on land-birds recorded during visits sea crossings. None of the islands has a beach; landings are to the islands reported here supplements that on seabirds made on rocks, generally on the northern side, where there is presented in Corella by Shaughnessy (2007), Shaughnessy and some protection from southerly swells. Dennis (2007) and Shaughnessy et al. (2008). -

Appendix 7-2 Protected Matters Search Tool (PMST) Report for the Risk EMBA

Environment plan Appendix 7-2 Protected matters search tool (PMST) report for the Risk EMBA Stromlo-1 exploration drilling program Equinor Australia B.V. Level 15 123 St Georges Terrace PERTH WA 6000 Australia February 2019 www.equinor.com.au EPBC Act Protected Matters Report This report provides general guidance on matters of national environmental significance and other matters protected by the EPBC Act in the area you have selected. Information on the coverage of this report and qualifications on data supporting this report are contained in the caveat at the end of the report. Information is available about Environment Assessments and the EPBC Act including significance guidelines, forms and application process details. Report created: 13/09/18 14:02:20 Summary Details Matters of NES Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act Extra Information Caveat Acknowledgements This map may contain data which are ©Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia), ©PSMA 2010 Coordinates Buffer: 1.0Km Summary Matters of National Environmental Significance This part of the report summarises the matters of national environmental significance that may occur in, or may relate to, the area you nominated. Further information is available in the detail part of the report, which can be accessed by scrolling or following the links below. If you are proposing to undertake an activity that may have a significant impact on one or more matters of national environmental significance then you should consider the Administrative Guidelines on Significance. World Heritage Properties: 11 National Heritage Places: 13 Wetlands of International Importance: 13 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park: None Commonwealth Marine Area: 2 Listed Threatened Ecological Communities: 14 Listed Threatened Species: 311 Listed Migratory Species: 97 Other Matters Protected by the EPBC Act This part of the report summarises other matters protected under the Act that may relate to the area you nominated. -

Australian Sea Lions Neophoca Cinerea at Colonies in South Australia: Distribution and Abundance, 2004 to 2008

Vol. 13: 87–98, 2011 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published online January 17 doi: 10.3354/esr00317 Endang Species Res OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Australian sea lions Neophoca cinerea at colonies in South Australia: distribution and abundance, 2004 to 2008 Peter D. Shaughnessy1,*, Simon D. Goldsworthy2, Derek J. Hamer3, 5, Brad Page2, Rebecca R. McIntosh4 1South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000, Australia 2South Australian Research and Development Institute, PO Box 120, Henley Beach, South Australia 5022, Australia 3Department of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia 4Department of Zoology, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria 3068, Australia 5Present address: Australian Antarctic Division, 203 Channel Highway, Kingston, Tasmania 7050, Australia ABSTRACT: The Australian sea lion Neophoca cinerea is an endemic species listed as vulnerable under the Commonwealth ‘Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act’ and as Endangered by IUCN. Assessing its abundance is difficult because of its supra-annual (17 to 18 mo) breeding cycle, and pupping seasons that are extended (about 6 mo but varying between colonies) and asynchronous in their timing between colonies. Based mainly on surveys at most sites in South Australia (SA) between 2004 and 2008, and information from the literature, estimates of abundance are provided for 39 breeding colonies and 9 haulout sites where pups are recorded occasionally. From this study it is estimated that in SA, 3119 Australian sea lion pups are born per breeding cycle, an increase on former estimates by at least 16% resulting from recognition of new breeding colonies, targeting surveys to coincide with maximum pup numbers and using mark-recapture procedures at some colonies.