FINAL VOL 2 PRE-BOMBING.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Sikh Secessionist Movement in Western Liberal Democracies

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 18 [Special Issue – September 2012] The Evolution of Sikh Secessionist Movement in Western Liberal Democracies Dr. Shinder Purewal Professor Department of Political Science Kwantlen Polytechnic University Surrey, Canada, V3W 2M8 This paper focuses on the evolution of Sikh secessionist movement in Western democracies. It explains how and why a segment of émigré Sikh community turned against the Indian state? The paper has divided this separatist movement in three distinct periods: (i) The politics of ‘Sikh Home Rule’ movement from 1960’s to 1978; (ii) Terrorist Movement for Khalistan from 1978 to 1993, and (iii) the politics of ‘grievance’, from 1994 to present. The first period witnessed the rise of a small group of Sikh separatists in Britain and the United Sates, as minor pawns of Cold War politics in the South Asian context. The second period witnessed the emergence of a major terrorist network of Sikh militants armed, trained and, to certain extent, financed by Pakistan, as battle-lines were drawn between two superpowers in Afghan war theatre. The third period has witnessed the decline of militancy and violence associated with Sikh secessionist movement, and the adoption of a new strategy cloaked in the language of justice and human rights. In the post war period, most Western societies had very little population of Sikh immigrants, and, with the exception of the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US), many had very little interest in South Asia. Sikh soldiers serving with the British army were the first to settle in Canada, the UK and the US. -

FINAL READER's GUIDE FRENCH JUNE 10TH.Indb

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. Le vol 182 d’Air India Une tragédie canadienne GUIDE DU LECTEUR ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Public Works and Government Services, 2010 Cat. -

11 July 2006 Mumbai Train Bombings

11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings July 2006 Mumbai train bombings One of the bomb-damaged coaches Location Mumbai, India Target(s) Mumbai Suburban Railway Date 11 July 2006 18:24 – 18:35 (UTC+5.5) Attack Type Bombings Fatalities 209 Injuries 714 Perpetrator(s) Terrorist outfits—Student Islamic Movement of India (SIMI), Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT; These are alleged perperators as legal proceedings have not yet taken place.) Map showing the 'Western line' and blast locations. The 11 July 2006 Mumbai train bombings were a series of seven bomb blasts that took place over a period of 11 minutes on the Suburban Railway in Mumbai (formerly known as Bombay), capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and India's financial capital. 209 people lost their lives and over 700 were injured in the attacks. Details The bombs were placed on trains plying on the western line of the suburban ("local") train network, which forms the backbone of the city's transport network. The first blast reportedly took place at 18:24 IST (12:54 UTC), and the explosions continued for approximately eleven minutes, until 18:35, during the after-work rush hour. All the bombs had been placed in the first-class "general" compartments (some compartments are reserved for women, called "ladies" compartments) of several trains running from Churchgate, the city-centre end of the western railway line, to the western suburbs of the city. They exploded at or in the near vicinity of the suburban railway stations of Matunga Road, Mahim, Bandra, Khar Road, Jogeshwari, Bhayandar and Borivali. -

![Download Entire Journal Volume No. 2 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8223/download-entire-journal-volume-no-2-pdf-1858223.webp)

Download Entire Journal Volume No. 2 [PDF]

JOURNAL OF PUNJAB STUDIES Editors Indu Banga Panjab University, Chandigarh, INDIA Mark Juergensmeyer University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Gurinder Singh Mann University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Ian Talbot Southampton University, UK Shinder Singh Thandi Coventry University, UK Book Review Editor Eleanor Nesbitt University of Warwick, UK Editorial Advisors Ishtiaq Ahmed Stockholm University, SWEDEN Tony Ballantyne University of Otago, NEW ZEALAND Parminder Bhachu Clark University, USA Harvinder Singh Bhatti Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Anna B. Bigelow North Carolina State University, USA Richard M. Eaton University of Arizona, Tucson, USA Ainslie T. Embree Columbia University, USA Louis E. Fenech University of Northern Iowa, USA Rahuldeep Singh Gill California Lutheran University, Thousand Oaks, USA Sucha Singh Gill Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Tejwant Singh Gill Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, INDIA David Gilmartin North Carolina State University, USA William J. Glover University of Michigan, USA J.S. Grewal Institute of Punjab Studies, Chandigarh, INDIA John S. Hawley Barnard College, Columbia University, USA Gurpreet Singh Lehal Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Iftikhar Malik Bath Spa University, UK Scott Marcus University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Daniel M. Michon Claremont McKenna College, CA, USA Farina Mir University of Michigan, USA Anne Murphy University of British Columbia, CANADA Kristina Myrvold Lund University, SWEDEN Rana Nayar Panjab University, Chandigarh, INDIA Harjot Oberoi University -

1 Revue De Presse 14-30 Juin 2019 La Compagnie Indienne Indigo a Créé

1 Revue de presse 14-30 juin 2019 La compagnie indienne IndiGo a créé la surprise en se tournant vers CFM International pour lui commander des LEAP-1A qui viendront motoriser 280 Airbus A320neo et A321neo. La compagnie indienne était pourtant cliente de lancement du PW1100G-JM de Pratt & Whitney dans le pays en 2016, avec 79 monocouloirs remotorisés d'Airbus en flotte aujourd'hui. La coentreprise de Safran Aircraft Engines et GE précise que ce contrat, qui comprend des moteurs en spare et un volet entretien à long terme, est estimé à plus de 20 milliards de dollars. Le premier A320neo motorisé par des LEAP est attendu par la compagnie indienne en 2020. IndiGo avait essuyé les plâtres avec ses GTF, avec de nombreuses AOG liées aux moteurs ainsi que des limitations opérationnelles. Le LEAP-1A équipe aujourd'hui les monocouloirs remotorisés des compagnies indiennes Air India et Vistara. Le Journal de l’Aviation 18/06/2019 Airbus a finalement confirmé lundi le lancement de l’A321XLR, version de l’A321neo au rayon d’action porté à 4700nm. Le premier client annoncé est la société de leasing Air Lease Corp, qui en veut 27 sur une commande visant cent monocouloirs dont 50 A220-300 et 23 A321neo. Lancé ce 17 juin 2019 au premier jour du Salon du Bourget « à la suite des réactions très positives du marché », l’A321XLR offrira à partir de 2023 une autonomie « sans précédent et Xtra longue » pouvant atteindre 4700 nm, soit 15% de plus que l’A321LR et avec le « même rendement énergétique imbattable ». -

White Paper the Punjab Agitation

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA WHITE PAPER ON THE PUNJAB AGITATION NEW DELHI, JULY 10, 1984 1 > < ■ WHITE PAPER ON THE PUNJAB AGITATION CONTENTS Pages I. INTRODUCTION . ...................................... ......... ...... II. DEMANDS OF THE SHIROMANI AKALI DAL AND GOVERNMENT R ESPO N SE ....................................... 5_ 22 III. TERROR AND VIOLENCE IN PUNJAB .... 23— 42 IV. ARMY ACTION IN PUNJAB AND CHANDIGARH . 43—53 V. SOME ISSUES ................................................................. 54— 58 ANNEXURES I. List of 45 demands received from the Akali Dal by the Government in September 1981 ..... 61 63 II. Revised list of 15 demands received from the Akali Dal by Government in October 1981 ..... 64-65 III. Anandpur Sahib Resolution authenticated by Sant Har- chand Singh L o n g o w a l . .............................................67_____ 90 I V . Calendar of meetings with the representatives of the Akali Dal, 1981—84 91—97 V. Statement of Home Minister in Parliament on February 28,1984 98— 104 V I. Prime Minister’s broadcast to the nation on June 2, J9 ^ 4 105— 109 VII. Calendar of main incidents of violence in Punjab during 1981^84 ..... 110— 162 V III. Excerpts from the statements of Shri Jarnail Singh Bhindran - wa^e ••••••.«.. 163-164 IX . Text of a Resolution Adopted by Parliament on April 29, x982 165 X. Layout of the Golden Temple and adjacent buildings . 167 X I. Details of civilian & army casualties and of arms & amm 1 - nition recovered upto June 30, 1984 . .169-170 PHOTOGRAPHS r t I INTRODUCTION Punjab has been the scene of a series of agitations during the last three years. Four distinct factors were noticeably at work. -

Air India 182 Press

AIR INDIA182 ACCLAIMED FILM ABOUT AIR INDIA BOMBINGS NOMINATED FOR DONALD BRITTAIN AWARD After an explosive premiere at the Hot Docs Festival where it was hailed as “compelling, poignant... the definitive film about the Air India tragedy and the most important documentary of the past few years", Air India 182 was broadcast commercial-free in primetime by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation on the anniversary of the flight's departure from Canada 24 years ago. Now, Air India 182 has been nominated for the Donald Brittain Award for Best Social and Political documentary at the 2009 Gemini Awards. The Awards ceremony will be televised nationally in Canada on Nov. 14, 2009 The powerful, intelligent and provocative film recounts the final hours, days and weeks before the plane disappeared off Irish radar screens. It reveals the story of how Canada’s first major counter-terrorism operation failed to thwart the conspiracy and lays bare the 'perfect storm' of errors that resulted in the world's most lethal act of aviation terrorism before 9/11. Filmmaker Sturla Gunnarsson gained unprecedented access to those directly involved, including the families of those who died and to key CSIS and RCMP investigators. Court documents, de-classified CSIS reports and inquiry transcripts provide the factual framework for the dramatic reconstructions. Family members speak directly of their tragic loss and express outrage at the failure of Canadian authorities to bring the perpetrators to justice. “The conspiracy was Vancouver-based, most of the victims were Canadian and it has profound implications about the way we think of ourselves and the society we live in,” says Gunnarsson. -

INDIA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

INDIA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 26 August 2011 INDIA 26 AUGUST 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN INDIA FROM 13 AUGUST TO 26 AUGUST 2011 News sources for further information REPORTS ON INDIA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 13 AUGUST AND 26 AUGUST 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 National holidays .................................................................................................. 1.10 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.12 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Mumbai terrorist attacks, November 2008 ......................................................... 3.03 General Election of April-May 2009 ..................................................................... 3.08 Naxalite (Maoist) counter-insurgency ................................................................. 3.15 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................................... 4.01 Overview of significant events, May 2010 to 12 August 2011 .......................... 4.01 5. CONSTITUTION ......................................................................................................... -

Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale - Life, Mission, and Martyrdom

1 # siVgUr pqsAid @ SANT JARNAIL SINGH BHINDRANWALE - LIFE, MISSION, AND MARTYRDOM by Ranbir S. Sandhu ***** May 1997 ***** Sikh Educational and Religious Foundation, P.O. Box 1553, Dublin, Ohio 43017 SANT JARNAIL SINGH BHINDRANWALE'S LIFE, MISSION AND MARTYRDOM ***** 0 INTRODUCTION In June 1984, the Indian Government sent nearly a quarter million troops to Punjab, sealed the state from the rest of the world, and launched an attack, code-named 'Operation Bluestar', on the Darbar Sahib complex in Amritsar and over forty other gurdwaras1 in Punjab. Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, head of the Damdami Taksaal2, and many students and teachers belonging to the Taksaal, perished in the conflict. Several thousand men, women and children, mostly innocent pilgrims, also lost their lives in that attack. This invasion was followed by 'Operation Woodrose' in which the army, supported by paramilitary and police forces, swept through Punjab villages to eliminate 'anti-social elements'. These 'anti-social' elements were identified as Amritdharis3. Instructions given to the troops at that time stated4: 'Some of our innocent countrymen were administered oath in the name of religion to support extremists and actively participate in the act of terrorism. These people wear a miniature kirpan5 round their neck and are called Amritdhari ... Any knowledge of the 'Amritdharis' who are dangerous people and pledged to commit murders, arson and acts of terrorism should immediately be brought to the notice of the authorities. These people may appear harmless from outside but they are basically committed to terrorism. In the interest of all of us their identity and whereabouts must always be disclosed.' These instructions constituted unmistakably clear orders for genocide of all Sikhs formally initiated into their faith. -

Counterterrorism: Punjab a Case Study

COUNTERTERRORISM: PUNJAB A CASE STUDY Charanjit Singh Kang B.A. (First Class Honours), Simon Fraser University, 200 1 Diploma of Criminology, Kwantlen University College, 1998 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the School of Criminology O Charanjit Singh Kang 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Charanjit Singh Kang Degree: M.A. Title of Thesis: Counterterrorism: Punjab A Case Study Examining Committee: Chair: Prof. Neil Boyd Professor, School of Criminology Dr. Raymond Corrado Professor, School of Criminology Dr. William Glackman Associate Professor, School of Criminology Dr. Irwin Cohen External Examiner Professor, Department of Criminology University College of the Fraser Valley Date DefendedIApproved: &I 6; 20s s SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

1984 Sikhs Kristallnacht

Twenty-five years on... 1984 Sikhs’ Kristallnacht Four Sikh brothers, the owners of the burning Sahni Paints, are roasted alive by mobs; Paharganj, New Delhi, 1984 Parvinder Singh Introduction An image still haunts me, even after twenty-five years. Ashok Vahie’s lense had captured the beginnings of a horrible sequence of events, a Kristallnacht of India’s Sikhs. On a wide and leafy British built New Delhi road, a terrified Sikh man is sitting, cross-legged while a group of men casually take turns in attacking him. Despite being a minority in India, Sikhs had climbed up the heights of Indian society with the help of their strong work ethic. To the wider Hindu community though, it was time they were cut down to size. Half a century earlier, another minority community, the Jews, faced similar challenges in Europe. Sikhs have a lot in common with the people of the Jewish faith. Both share an healthy and positive optimism in their attitude to life in the face of adversity. Both have faced centuries of persecution. The month of November has brought them together. In November 1938, a German embassy official, Ernst vom Rath, was assassinated by a Jewish teenager, Herschel Grynszpan, in revenge of the mass expulsion of his people to Poland. Kristallnacht or the ‘Night of Broken Glass’, though portrayed by the German authorities as a spontaneous 1 November 1984, New Delhi, India. Photo by Ashok Vahie outburst of popular outrage, were actually pogroms organised by Hitler’s Nazis. Synagogues and Jewish businesses were particular targets, while the police and fire brigade looked on. -

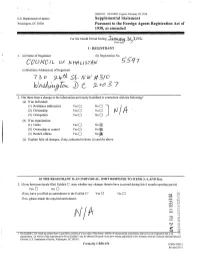

Council of Ichfluzrm B'547 (C) Business Address(Es) of Registrant 7 3 0 %^Tk Si, A/ U/ #3/O

OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 U.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended r For Six Month Period Ending JfyrwHAiy|_3_j b\yJl0)'X ' (Insert date/ I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Council of icHfluzrM b'547 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 7 3 0 %^tk Si, A/ U/ #3/O 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) YesD NoD (2) Citizenship YesD NoD rJlA (3) Occupation YesD NoD J (b) If an organization: (1) Name YesQ No a (2) Ownership or control YesD Nop, (3) Branch offices YesD No a (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3, 4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No n Ifyes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes __ No • rsj If no, please attach the required amendment. |ss3 m m C3 /v CO 15 TO r\> o 1 The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy ofthe charter, articles ot incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an JTS organization. (A waiver ofthe requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S.