Radio Deregulation and Consolidation: What Is in the Public Interest?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concentrator 20

United States Patent (9. 11 Patent Number: 4,789,983 Acampora et al. (45) Date of Patent: Dec. 6, 1988 (54) WIRELESS NETWORK FOR WIDEBAND Acampora, IEEE Jrnl on SAC, vol. SAC-1, Jan. 1983, NDOOR COMMUNICATIONS pp. 133-142. Acampora et al., IEEE Communications Magazine, "75) Inventors: Anthony Acampora, Freehold; Jack vol. 22, No. 8, Aug. 1984, pp. 12-21. H. Winters, Middletown, both of Mednick, Globecom '85, New Orleans, La., vol. 1, pp. N.J. 15.2.1 to 15.2.6. 73) Assignee: American Telephone and Telegraph Yen et al., Globecom '85, New Orleans, La., vol. 3, pp. Co., AT&T Bell Laboratories, 39.1.1 to 39.14. Murray Hill, N.J. Primary Examiner-Douglas W. Olms (21) Appl. No.: 22,255 Assistant Examiner-Melvin Marcelo Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Erwin W. Pfeifle (22 Filed: Mar. 5, 1987 57 ABSTRACT 51) Int. Cl'................................................ H04J 3/14 The present invention relates to a wideband communi 52 U.S.C. ......................................... 370/96; 370/84 cation network using wireless radio transmissions either 58) Field of Search ..................... 370/94, 95, 96, 109, on a stand-alone basis or to supplement a hard-wired 370/29, 13.1, 17, 97, 84; 379/58, 61, 63; 371/5 network. The exemplary network comprises (a) a plu rality of transceivers associated with separate users of (56) References Cited the network; (b) optionally at least one concentrator U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS associated with certain separate subgroups of wireless 4,251,865 2/1981 Moore et al. ......................... 370/96 and possibly hard-wired transceivers for providing du 4,301,533 11/1981 Acampora et al. -

Chapter 4. Political Influence on Media

distribute or BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI / Contributor / Getty Images post,4 POLITICAL INFLUENCE copy,ON MEDIA his chapter considers the influence of political forces on the media and explores questions about Tthe appropriate role of government in regulating media. (Later, in Chapter 9, we will look at the media’snot influence on society, including politics.) Our concern is not with the details of media legisla- tion but rather with the general dynamics that characterize the relationship between government and media. We also address the more informal political pressure brought to bear on the media by media Do advocacy groups, public interest organizations, religious groups, and media critics. Copyright ©2019 by SAGE Publications, Inc. 107 This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. 108 Part III ■ Industry MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY The nonprofit watchdog group Reporters Without Borders listed three democratic countries—Norway, Sweden, and Finland—at the top of its 2017 annual Press Freedom Index, and three countries with authoritarian governments—Turkmenistan, Eritrea, and North Korea—at the bottom of the list. (The United States ranked 43rd of the 180 countries in the report.) The Index was constructed from several criteria, including the amount of violence against journalists, the nature of legislation governing media, and the degree of economic pressures on the media (Reporters Without Borders 2017). Reporters Without Borders Secretary-General Christophe Deloire has noted that the Index “does not take direct account of the kind of political system but it is clear that democracies provide better protection for the freedom to produce and circulate accurate news and information than countries where human rights are flouted.” But being in a democracy does not mean the media are totally unconstrained. -

Making Radio Pirates Walk the Plank with Aiding and Abetting Liability

Arrr! Sever Thee Transmitters! Making Radio Pirates Walk the Plank with Aiding and Abetting Liability Max Nacheman * TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 299 II. THE INTERTWINED FATE OF BROADCAST REGULATION AND PIRATE RADIO ............................................................................................. 301 A. Origins of Radio Broadcast Regulation in the United States .. 301 B. Pirates of the (Air)waves: The Swell of Unauthorized Broadcasting ............................................................................ 303 C. From Radio Pirates to Cellular Ninjas: The Future of Unauthorized Broadcasting ..................................................... 304 III. UNAUTHORIZED BROADCASTING POSES A UNIQUE ENFORCEMENT CHALLENGE THAT MAY BE ADDRESSED BY ESTABLISHING AUTHORITY TO CRACK DOWN ON AIDERS AND ABETTORS OF PIRATE BROADCASTERS .............................................................................. 305 A. The FCC’s Enforcement Procedure for Unauthorized Broadcasters Is an Inadequate Deterrent to Pirates ............... 306 B. Aiding and Abetting Liability Would Cut the Supply Chain of Essential Resources to Unauthorized Broadcasters ................ 309 1. How the United Kingdom Sank Pirate Radio ................... 310 2. Aiding and Abetting Liability for Securities Violations ... 311 IV. THREE WAYS TO CRACK DOWN ON AIDERS AND ABETTORS OF UNAUTHORIZED BROADCASTING: STATUTE, RULEMAKING, AND EXISTING CRIMINAL LAW ............................................................. -

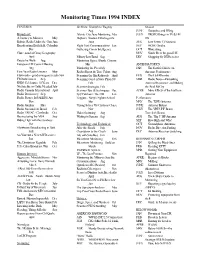

Monitoring Times 2000 INDEX

Monitoring Times 1994 INDEX FEATURES: Air Show: Triumph to Tragedy Season Aug JUNE Duopolies and DXing Broadcast: Atlantic City Aero Monitoring May JULY TROPO Brings in TV & FM A Journey to Morocco May Dayton's Aviation Extravaganza DX Bolivia: Radio Under the Gun June June AUG Low Power TV Stations Broadcasting Battlefield, Colombia Flight Test Communications Jan SEP WOW, Omaha Dec Gathering Comm Intelligence OCT Winterizing Chile: Land of Crazy Geography June NOV Notch filters for good DX April Military Low Band Sep DEC Shopping for DX Receiver Deutsche Welle Aug Monitoring Space Shuttle Comms European DX Council Meeting Mar ANTENNA TOPICS Aug Monitoring the Prez July JAN The Earth’s Effects on First Year Radio Listener May Radio Shows its True Colors Aug Antenna Performance Flavoradio - good emergency radio Nov Scanning the Big Railroads April FEB The Half-Rhombic FM SubCarriers Sep Scanning Garden State Pkwy,NJ MAR Radio Noise—Debunking KNLS Celebrates 10 Years Dec Feb AntennaResonance and Making No Satellite or Cable Needed July Scanner Strategies Feb the Real McCoy Radio Canada International April Scanner Tips & Techniques Dec APRIL More Effects of the Earth on Radio Democracy Sep Spy Catchers: The FBI Jan Antenna Radio France Int'l/ALLISS Ant Topgun - Navy's Fighter School Performance Nov Mar MAY The T2FD Antenna Radio Gambia May Tuning In to a US Customs Chase JUNE Antenna Baluns Radio Nacional do Brasil Feb Nov JULY The VHF/UHF Beam Radio UNTAC - Cambodia Oct Video Scanning Aug Traveler's Beam Restructuring the VOA Sep Waiting -

The Logic of Scarcity: Idle Spectrum As a First Amendment Violation

BENJAMIN 10/28/02 2:07 PM Duke Law Journal VOLUME 52 OCTOBER 2002 NUMBER 1 THE LOGIC OF SCARCITY: IDLE SPECTRUM AS A FIRST AMENDMENT VIOLATION STUART MINOR BENJAMIN† ABSTRACT The Supreme Court has distinguished the regulation of radio spectrum from the regulation of printing presses, and applied more lenient scrutiny to the regulation of spectrum, based on its conclusion that the spectrum is unusually scarce. The Court has never confronted an allegation that government actions resulted in unused or underused frequencies, but there is good reason to believe that such government- created idle frequencies exist. Government limits on the number of printing presses almost assuredly would be subject to heightened scrutiny and would not survive such scrutiny. This Article addresses the question whether the scarcity rationale—or any other reasoning— supports distinguishing spectrum from print such that government ac- tions constricting the supply of spectrum would pass muster. I argue that the scarcity rationale does not support, and instead undercuts, government actions that limit the use of the spectrum. Government decisions that exacerbate the problems that gave rise to government regulation in the first place subvert the entire justification Copyright © 2002 by Stuart Minor Benjamin. † Rex G. & Edna Baker Professor in Constitutional Law, University of Texas School of Law. B.A., Yale University, 1987; J.D., Yale Law School, 1991. I would like to thank Akhil Amar, David Anderson, Tom Bell, Mitch Berman, James Boyle, Stuart Buck, Douglas Galbi, Nicole Garnett, Dale Hatfield, Thomas Hazlett, Ken Katkin, Doug Laycock, Doug Lichtman, Mike Marcus, Neil Netanel, Arti Rai, Kathleen Sullivan, Eugene Volokh, Douglas Webbink, and Phil Weiser for helpful comments, and Jessica Mederson for research assistance. -

Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

Federal Communications Commission FCC 99-6 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 ) In the Matter of ) MM Docket No. 99-25 ) Creation of a Low ) RM-9208 Power Radio Service ) RM-9242 ) ) NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULE MAKING Adopted: January 28, 1999 Released: February 3, 1999 Comment Date: April 12, 1999 Reply Comment Date: May 12, 1999 By the Commission: Chairman Kennard and Commissioner Tristani issuing a joint statement; Commissioners Ness and Powell issuing separate statements; and Commissioner Furchtgott-Roth dissenting and issuing a statement. I. INTRODUCTION 1. By this Notice, we are proposing to establish rules authorizing the operation of new, low power FM (LPFM) radio stations. In particular, we are proposing to create two classes of low power radio service, both of which would operate in the existing FM radio band: a 1000-watt primary service and a 100-watt secondary service. We also seek comment on whether to establish a third, "microradio" class of low power radio service that would operate in the range of 1 to 10 watts on a secondary basis. These proposals are in response to two petitions for rule making and related comments indicating substantial interest in, and public support for, increased citizens' access to the airwaves. We believe that these new LPFM stations would provide a low-cost means of serving urban communities and neighborhoods, as well as populations living in smaller rural towns and communities. In creating these new classes of stations, our goals are to address unmet needs for community-oriented radio broadcasting, foster opportunities for new radio broadcast ownership, and promote additional diversity in radio voices and program services. -

A Can of Worms

A CAN OF WORMS Pirate Radio as Public Intransigence on the Public Airwaves by John Nathan Anderson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Journalism and Mass Communication) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2004 APPROVED ____________________________ James L. Baughman, Professor and Director ____________________________ Robert E. Drechsel, Professor ____________________________ Douglas M. McLeod, Professor and Advisor Contents Preface i Chapter 1. UNLICENSED BROADCASTING AS RADIO HISTORY 1 Scope of Study 3; Organizational Outline of Chapters 5; Overview of Source Material 8; Notes to Chapter 1 14 Chapter 2. CONTEMPORARY TREATMENT OF UNLICENSED BROADCASTING 16 Real-World Constraints on FCC Enforcement 18; Engagement at the Administrative Level 21; Notes to Chapter 2 30 Chapter 3. EARLY RADIO LICENSING AUTHORITY: A CRISIS OF CONFIDENCE 36 1912-1927: Undermined from the Inside 36; 1927/34 Legislation, “Public interest, convenience, and necessity,” and “Access” to the Airwaves 41; Notes to Chapter 3 46 Chapter 4. LEGAL REFINEMENT OF FCC LICENSING AUTHORITY 50 Bedrocks Established in Case Law, 1943-1969 55; FCC License Authority and Enforcement Effectiveness, 1970-1989 60; Notes to Chapter 4 67 Chapter 5. MICRORADIO: FOCUSED CHALLENGE TO THE LICENSING REGIME 72 Stephen Dunifer and Free Radio Berkeley’s “Can of Worms” 73; Other Notable Microradio Cases 78; Microradio and FCC Field Enforcement 82; Notes to Chapter 5 88 Chapter 6. THE FCC AND LPFM 95 Congressional Meddling Into LPFM -

Copyright by Philip Daniel Goetz 2006

Copyright by Philip Daniel Goetz 2006 Low Power FM Broadcasting: A Survey Snapshot of the Field by Philip Daniel Goetz, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2006 Low Power FM Broadcasting: A Survey Snapshot of the Field Approved by Supervising Committee: __________________________ __________________________ Abstract Low Power FM Broadcasting: A Survey Snapshot of the Field Philip Daniel Goetz, MA The University of Texas at Austin 2006 Supervisor: Kathleen Tyner This study focuses on the current activities of licensed low power FM (LPFM) radio stations. Drawing attention to these stations reveals their struggles, successes and hopefully, adds listeners to their audience. It discusses the initiation of LPFM broadcasting in 2000 from two perspectives: regulatory and activist. A presentation of general station characteristics follows using evidence from a questionnaire delivered to seven hundred seventeen (717) stations. Two specific focuses of the questionnaire are listener feedback and localism. This study argues for expanded licensing by describing LPFM stations as an accessible community media that adds diversity to the marketplace of ideas. iv Table of contents List of Tables ………………………………………………………………….…...…......v Introduction…………………………………………………………………...……….......1 History …………………………………….........................................................................4 -

Community Radio, Public Interest: the Low Power Fm Service and 21St Century Media Policy Margo L

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2009 Community Radio, Public Interest: The Low Power Fm Service and 21st Century Media Policy Margo L. Robb University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons Robb, Margo L., "Community Radio, Public Interest: The Low Power Fm Service and 21st Century Media Policy" (2009). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 315. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/315 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMUNITY RADIO, PUBLIC INTEREST: THE LOW POWER FM SERVICE AND 21 st CENTURY MEDIA POLICY A Thesis Presented by MARGO L. ROBB Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 2009 Department of Communication COMMUNITY RADIO, PUBLIC INTEREST: THE LOW POWER FM SERVICE AND 21 st CENTURY MEDIA POLICY A Thesis Presented by MARGO L. ROBB Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________________ Mari Castañeda, Chair ____________________________________________ Sut Jhally, Member __________________________________________ Douglas L. Anderton, Acting Department Head Department of Communication DEDICATION To my amazing family: James Carrott, my husband Amelia and Beatrix, my daughters and Bruce and Janet Robb, my parents L. Bob Rife laughs. “Y’know, watching government regulation trying to keep up with the world is my favorite sport. -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 98-117 Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission FCC 98-117 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 ) ) ) ) In the Matter of ) ) 1998 Biennial Regulatory Review -- ) MM Docket No. 98-93 Streamlining of Radio Technical Rules in ) Parts 73 and 74 of the Commission's Rules ) ) ) ) ) ) NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULE MAKING AND ORDER Adopted: June 11, 1998 Released: June 15, 1998 Comment Date: [60 days from the date of publication in the Federal Register] Reply Date: [90 days from the date of publication in the Federal Register] By the Commission: Commissioner Furchtgott-Roth issuing a statement. Table of Contents Paragraph I. Introduction .........................................................1 II. Negotiated Interference in the FM Service ...................................3 A. Introduction .......................................................3 B. Background .......................................................4 C. Specific Proposals ..................................................11 1. Involving Applications for Coordinated FM Federal Communications Commission FCC 98-117 Station Changes ..........................................11 2. Agreements Involving Applications That Would Cause New or Increased Interference ......................................17 III. Other Proposals to Give Station's Greater Technical Flexibility ...................28 A. Introduction .......................................................28 B. Point-To-Point Prediction Methodology ..................................29 C. Commercial FM Technical Requirements: -

Localism As a Discursive Boundary Object in Low-Power Radio Policymaking

Communication, Culture & Critique ISSN 1753-9129 ORIGINAL ARTICLE What’s Local? Localism as a Discursive Boundary Object in Low-Power Radio Policymaking Christina Dunbar-Hester Journalism and Media Studies, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA This article addresses the discourse of ‘‘localism’’ used in the formulation of low-power FM radio service in the United States. It builds on S. L. Star and J. Griesemer’s (1989) concept of ‘‘boundary object’’ to theorize localism as a ‘‘discursive boundary object.’’ Drawing on interviews with advocates and regulators, participant observation with low-power radio activists, and documentary research in relevant policy discussions, the article argues that ‘‘localism’’ moved across discourse communities and effaced differences for groups who otherwise might not have agreed. ‘‘Localism’’ was also polemically deployed at the level of national policy. Its unique potency may be seen in the seeming inability of even actors who opposed the introduction of low-power FM radio service to oppose localism outright. doi:10.1111/cccr.12027 It is difficult to define ‘‘localism.’’ One reason for this is that the concept is recursive: to make sense of what is ‘‘local,’’ people often employ other related vocabulary that borders on being indexical,1 such as ‘‘close to home,’’ or ‘‘oriented toward a local community.’’2 Indeed, even scholars and policymakers rarely bother to define what they mean when they invoke localism (see Hilliard & Keith 2005, p. 65). Another reason is simply that ‘‘localism’’ is a fluid, even protean concept. This article addresses the discourse of ‘‘localism’’ as deployed by a range of groups in the recent policy discussion over the formulation of the low-power FM (LPFM) radio service in the United States in 1990–2000. -

Annual Report 2001 PORTFOLIO of STATIONS

Annual Report 2001 PORTFOLIO OF STATIONS ■ Redding, CA St. Cloud, MN ■ ■ Watertown, NY ■ ■ Chico, CA Flint, MI ■ Albany, NY Grand Rapids, MI ■ ■ Utica-Rome, NY Erie, PA ■ Peoria, IL ■ Covington, KY ▲ ■ El Paso, TX ■ Lafayette, LA Albany, NY El Paso, TX Grand Rapids, MI Peoria, IL St. Cloud, MN WQBJ(FM) KSII(FM) WLHT(FM) WGLO(FM) KMXK(FM) WQBK(FM) KLAQ(FM) WGRD(FM) WPPY(FM) WJON(AM) WABT(FM) KROD(AM) WTRV(FM) WRVP(FM) WWJO(FM) WGNA(FM) WNWZ(AM) WVEL(AM) KKSR(FM) WGNA(AM)# Erie, PA WFGR(FM)* WFYR(FM) KLZZ(FM) WTMM(AM) WXKC(FM) WIXO(FM) KXSS(AM) WRIE(AM) Lafayette, LA Chico, CA WXTA(FM) KMDL(FM) Redding, CA Utica-Rome, NY KFMF(FM) WQHZ(FM) KRKA(FM) KRRX(FM) WODZ(FM) KQPT(FM) KFTE(FM) KNNN(FM) WLZW(FM) KALF(FM) Flint, MI KTDY(FM) KQMS(AM) WFRG(FM) KZAP(FM) WCRZ(FM) KPEL(FM) KSHA(FM) WIBX(AM) WWBN(FM) KPEL(AM) KRDG(FM) WRUN(AM) WFNT(AM) KROF(AM) KNRO(AM) WZRZ(FM)* Watertown, NY WRXF(FM)* WCIZ(FM) WLSP(AM)* WFRY(FM) WTNY(AM) WNER(AM) * Stations indicated with an asterisk (*) are subject to acquisition by us under an existing agreement. # We have subsequently sold those stations with a (#). Regent Communications, Inc. (“Regent” or the “Company”) is a holding company in the radio broadcasting business. Regent was incorporated2001 in Delaware in November 1996 by Terry S. Jacobs and William L. Stakelin with the objective of acquiring radio properties, primarily in medium and smaller radio markets, that have a history of growing revenues and broadcast cash flow, have capable operating management and are in communities with good growth prospects or have attractive competitive environments.