Gustavo Sainz* an Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libro ING CAC1-36:Maquetación 1.Qxd

© Enrique Montesinos, 2013 © Sobre la presente edición: Organización Deportiva Centroamericana y del Caribe (Odecabe) Edición y diseño general: Enrique Montesinos Diseño de cubierta: Jorge Reyes Reyes Composición y diseño computadorizado: Gerardo Daumont y Yoel A. Tejeda Pérez Textos en inglés: Servicios Especializados de Traducción e Interpretación del Deporte (Setidep), INDER, Cuba Fotos: Reproducidas de las fuentes bibliográficas, Periódico Granma, Fernando Neris. Los elementos que componen este volumen pueden ser reproducidos de forma parcial siem- pre que se haga mención de su fuente de origen. Se agradece cualquier contribución encaminada a completar los datos aquí recogidos, o a la rectificación de alguno de ellos. Diríjala al correo [email protected] ÍNDICE / INDEX PRESENTACIÓN/ 1978: Medellín, Colombia / 77 FEATURING/ VII 1982: La Habana, Cuba / 83 1986: Santiago de los Caballeros, A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO / República Dominicana / 89 AS A PROLOGUE / IX 1990: Ciudad México, México / 95 1993: Ponce, Puerto Rico / 101 INTRODUCCIÓN / 1998: Maracaibo, Venezuela / 107 INTRODUCTION / XI 2002: San Salvador, El Salvador / 113 2006: Cartagena de Indias, I PARTE: ANTECEDENTES Colombia / 119 Y DESARROLLO / 2010: Mayagüez, Puerto Rico / 125 I PART: BACKGROUNG AND DEVELOPMENT / 1 II PARTE: LOS GANADORES DE MEDALLAS / Pasos iniciales / Initial steps / 1 II PART: THE MEDALS WINNERS 1926: La primera cita / / 131 1926: The first rendezvous / 5 1930: La Habana, Cuba / 11 Por deportes y pruebas / 132 1935: San Salvador, Atletismo / Athletics -

Volume 19, No. 2, Spring 2006

THE NORTHWEST LINGUIST Volume 19 No. 2, SPRING 2006 Meeting our Members INSIDE Each newsletter Katrin Rippel introduces one of our NOTIS or WITS members to the rest of the membership. This month, she presents a member who works with THIS ISSUE a language most of us know little about – ASL. 3 NOTIS Notes Language beyond words – meeting Cynthia Wallace 4 WITS Outreach By Katrin Rippel Committee Report “Culture is a set of learned behaviors physical space, facial expressions and body of a group of people who have their own 5 Scandinavia meets Asia movements to express grammar and pri- language, values, rules of behavior, and in the Pacific North- marily has a topic-comment sentence west traditions… The essential link to Deaf structure, while English uses a liniar, pri- Culture among the American deaf com- marily subject-verb-object sentence munity is American Sign Language” Carol structure,” she explains. 6 Technology meets Com- Padden* What was the greatest challenge for merce meets Culture! Cynthia Wallace is an American Sign you in learning this language? Language (ASL) interpreter. At first sight, “Learning the subtle movements of she appears serious in her black turtle 7 Meeting Our the language. For example, facial features neck, yet with my first question on how Members (cont.) such as eyebrow motion and lip-mouth she started with ASL her face brightened movements. These are vital parts of the up with a smile. “My college roommate grammatical system indicating sentence took ASL classes. When I saw her signing 8 Cash from crashes type or specifying size and shape, convey- a poem I was amazed by its beauty and I ing adjectives and adverbs. -

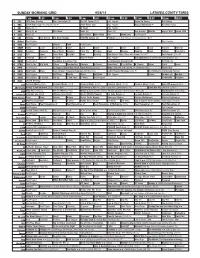

Sunday Morning Grid 9/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Tunnel to Towers Bull Riding 4 NBC 2014 Ryder Cup Final Day. (4) (N) Å 2014 Ryder Cup Paid Program Access Hollywood Å Red Bull Series 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild Exped. Wild 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Green Bay Packers at Chicago Bears. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program The Specialist ›› (1994) Sylvester Stallone. (R) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) La Arrolladora Banda Limón Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue (2012) Baby’s Day Out ›› (1994) Joe Mantegna. -

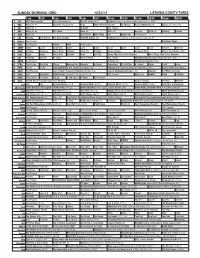

Sunday Morning Grid 12/21/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/21/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Kansas City Chiefs at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Young Men Big Dreams On Money Access Hollywood (N) Skiing U.S. Grand Prix. 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Outback Explore 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Atlanta Falcons at New Orleans Saints. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Christmas Angel 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Alsace-Hubert Heirloom Meals Man in the Kitchen (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Christmas Twister (2012) Casper Van Dien. (PG) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Mientras Que Carlos Mercenario Fue Vigésimo Segundo. La Competición

efectuada en el 1999 en Mezidom. En Francia el norteamericano Curt Clausen llegó en un muy meritorio undécimo lugar mientras que Carlos Mercenario fue vigésimo segundo. La competición femenina tuvo desde el principio el liderazgo de María Guadalupe Sánchez quien pasó los 5 Km al frente con 24:10 seguida a escasas cen- tésimas por su compatriota Victoria Pa- lacios y a nueve segundos por Mara Ibáñez, del equipo ¨B¨ de México que no confrontaba directamente por las meda- llas en la Copa, pero sí por la clasificación a los Juegos olímpicos, y la cubana Cruz Vera quien fue una grata revelación. Un poco más atrás las seguían las nor- teamericanas Armenta y Rohl. Al cumplirse la mitad de la prueba Ibáñez se encontraba en la primera colocación, 47:43 seguida de Sánchez, 47:45 y Palacios, 47:58. Esta última gran animadora hasta allí de la competencia será descalificada en los próximos kiló- metros. En los 15 Km ya María Guadalupe Sánchez estaba al frente, 1h11:17, con tres segundos sobre Ibáñez y diez sobre la experimentada Graciela Mendoza, campeona de los últimos Juegos Pana- mericanos con 1h34:19, mientras que más atrás con 1h11:40 pasaron la El mexicano Miguel Angel Rodríguez cubana Cruz Vera y la mexicana María del sido vigésimo quinta en agosto del 99 en Rosario Sánchez vice campeona pana- el Campeonato mundial de Sevilla donde mericana. Con estas posiciones se llega- María del Rosario finalizó 34º, Teresita rá al final en el cual Sánchez pudo estirar Collado 35º, e Irusta 36º y en la cual a trece segundos la diferencia sobre Mara Mendoza y Dow fueron descalificadas. -

|||GET||| Historicizing the Pan-American Games 1St Edition

HISTORICIZING THE PAN-AMERICAN GAMES 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Bruce Kidd | 9781138219830 | | | | | U.S. wins four golds in swimming Multi-sport event for nations on the American continents. Archived from the original on September 25, Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. The closing ceremony includes a fifteen-minute presentation from the next host city. The Pan American Games mascotan animal or human figure representing the cultural heritage of the host country, was introduced in in San Juan, Puerto Rico. February 1, While the inaugural Games hosted 2, participants representing 14 nations, the most recent Pan American Games involved 6, competitors from 41 countries. When athletics was scheduled for the last days, the men's marathon is held in the last day of the games, Historicizing the Pan-American Games 1st edition the award ceremony is held before or during the closing ceremonies. In track and field, Maria Colin of Mexico was awarded the kilometer walk title when the first-place finisher, Graciela Mendoza, also of Mexico, was disqualified. The draw, which took more than three hours to complete, began with a loud, bilingual and sometimes profane dispute over the procedure. September 4, President Adolfo Ruiz Cortines. Paramaribo, Suriname. Galdos, 29, took control of the match in the first set, using just 40 minutes to set the pace. Fontabelle, Saint Michael, Barbados. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Retrieved June 4, Kingstown, Saint Vincent. Mexico and Canada have hosted three Pan American Games Historicizing the Pan-American Games 1st edition, more than any other nation. Retrieved June 12, Colonial Phantoms. -

Federico Garcia Lorca En Buenos Aires Pedro Larrea Rubio

Federico Garcia Lorca en Buenos Aires Pedro Larrea Rubio · Madrid, Spain Master of Arts in Spanish, University of Virginia, 2008 Licenciado en Teoria de la Literatura y Literatura Comparada, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 2004 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty ofthe University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Spanish, Italian and Portuguese University of Virginia August, 2012 Andrew A. Anderson Herbert Tico Braun David T. Gies F emando Opere i © Copyright by Pedro Larrea Rubio All Rights Reserved August 2012 ii Abstract This dissertation deals with Federico Garcia Lorca's sojourn in Buenos Aires, Argentina, from October 1933 to March of 1934. In the first chapter, it offers a detailed account of Garcia Lorca‘s life experiences related to this period, filling the gaps left by previous biographers by paying attention to a myriad of Argentinean periodicals that scholars have overlooked so far. In the second chapter, I study the Argentinean theater of the first three decades of the 20th century in order to understand the dramatic art of the period and the context in which Garcia Lorca's plays were well received by critics and public. I also pay attention to the international, Spanish and Argentinean plays contemporary to Garcia Lorca‘s stay in Buenos Aires, focusing on those that Garcia Lorca saw performed, linking them with the poet‘s own final plays and studying the interactions between them. In the third chapter, I study the reasons for the success of Bodas de sangre, La zapatera prodigiosa and Mariana Pineda in the teatro Avenida in Buenos Aires, focusing on the reactions of critics, journalists and how Garcia Lorca‘s plays fit in the horizon of expectations of Buenos Aires audiences. -

Contents Campus and in the Community

Diversity The Intensive English Program Newsletter Volume 8, No. 2, Fall 2009 Editor's Note: The Intensive English (ESOL) Program at Lone Star College - Kingwood was founded in August 2001 to help immigrant and international students living in the community to learn and improve their English. One of the goals of the ESOL Program is to promote intercultural understanding and diversity on Contents campus and in the community. Diversity: The ESOL Student Newsletter plays an important role towards this goal. This issue of the Diversity has several themes: What I Like Most about My Country, Why I N eed to Improve My English, What I Like Most about the U.S., An Interesting or Funny Experience in What I Like Most the U.S., What Surprises Me Most about the U.S., Who is My Hero, This I Believe, and What Inspires About My Country Me. I hope you will enjoy reading these great stories. ...............1 If you have any comments about the newsletter, please e-mail Anne Amis at [email protected]. Why I Need to Improve My English What I Like Most about My Country ...............4 Patricio Bedon, Ecuador, Writing–High Beginning “With love today I want to sing, Yes sir, to my beautiful Ecuador and say that wherever I go, I am What I Like Most Ecuadorian.” These three lines are part of a song that we Ecuadorians sing with pride and with a strong About the U.S. voice to remember fondly our little piece of land. Ecuador is known around the world, despite the ...............6 fact that it is a small country, no bigger than Colorado. -

2018 Wtch.Qxp Walks F&F

IAAF WORLD RACE WALKING TEAM CHAMPIONSHIPS FACTS & FIGURES IAAF Race Walking World Cup 1961-2016 . .1 Team Results 1961-2016 . .4 Most Appearances in Finals . .9 Doping Disqualifications . .10 Youngest & Oldest . .10 Placing Tables . .11 Country Index . .13 World All-Time Road Walk Lists . .53 Major Walk Records . .54 IAAF (Senior) World Championships Walks Medallists . .56 Olympic Games Walks Medallists . .57 TAICANG 2018 ★ RACE WALKING TEAM CHAMPS, PAST TOP3s 1 IAAF RACE WALKING TEAM CHAMPIONSHIPS 1961-2016 Past Titles – 1961-1975: Lugano Trophy; 1977-1987 & 1991: IAAF Race Walking World Cup; 1989 & 1997 onwards: IAAF World Race Walking Cup; 1993 & 1995: IAAF/Reebok World Race Walking Cup. From 2016: IAAF World Race Walking Team Championships 2 Men Women 3 Date Venue Countries Total Athletes 20K 50K u20 10K 5/10/20K 50K u20 10K 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 (1) October 15/16, 1961 Lugano, SUI 4/10 24 12 12 - - - - 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 (2) October 12/13, 1963 Varese, ITA 6/12 36 18 18 - - - - 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 (3) October 9/10, 1965 Pescara, ITA 7/11 42 21 21 - - - - 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 (4) October 15, 1967 Bad Saarow, GDR 8/14 48 24 24 - - - - 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 (5) October 10/11, 1970 Eschborn, FRG 8/14 60 30 30 - - - - 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 (6) October 12/13, 1973 Lugano, SUI 9/18 68 35 35 - - - - 1 2 2 2 2 4 2 2 (7) October 11/12, 1975 Le Grand Quevilly, FRA 9/14 109 36 35 - 38 - - 1 2 2 2 2 4 2 2 (8) September 24/25, 1977 Milton Keynes, GBR 15/19 119 48 48 - 23 - - 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 (9) September 29/30, 1979 Eschborn, FRG 18/21 147 54 55 - 40 - - 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 (10) October 3/4, 1981 Valencia, ESP 18/23 160 58 59 - 49 - - 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 (11) September 24/25, 1983 Bergen, NOR 18/21 169 54 53 - 64 - - 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 (12) September 28/29, 1985 St. -

Obitel-Español-Portugués

ObservatóriO iberO-americanO da FicçãO televisiva Obitel 2020 O melOdrama em tempOs de streaming el melOdrama en tiempOs de streaming OBSERVATÓRIO IBERO-AMERICANO DA FICÇÃO TELEVISIVA OBITEL 2020 O MELODRAMA EM TEMPOS DE STREAMING EL MELODRAMA EN TIEMPOS DE STREAMING Coordenadores-gerais Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes Guillermo Orozco Gómez Coordenação desta edição Gabriela Gómez Rodríguez Coordenadores nacionais Morella Alvarado, Gustavo Aprea, Fernando Aranguren, Catarina Burnay, Borys Bustamante, Giuliana Cassano, Gabriela Gómez, Mónica Kirchheimer, Charo Lacalle, Pedro Lopes, Guillermo Orozco Gómez, Ligia Prezia Lemos, Juan Piñón, Rosario Sánchez, Luisa Torrealba, Guillermo Vásquez, Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes © Globo Comunicação e Participações S.A., 2020 Capa: Letícia Lampert Projeto gráfico e editoração: Niura Fernanda Souza Produção editorial: Felícia Xavier Volkweis Revisão do português: Felícia Xavier Volkweis Revisão do espanhol: Naila Freitas Revisão gráfica: Niura Fernanda Souza Editor: Luis Antônio Paim Gomes Foto de capa: Louie Psihoyos – High-definition televisions in the information era Bibliotecária responsável: Denise Mari de Andrade Souza – CRB 10/960 M528 O melodrama em tempos de streaming / organizado por Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes e Guillermo Orozco Gómez. -- Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2020. 407 p.; 14x21 cm. Edição bilíngue: El melodrama en tiempos de streaming ISBN: 978-65-5759-012-6 1. Televisão – Internet. 2. Comunicação e tecnologia – Tele- visão – Ibero-Americano. 3. Programas de televisão – Distribuição – Inter- net. 4. Televisão – Ibero-América. 4. Meios de comunicação social. 5. Co- municação social. I. Título: El melodrama en tiempos de streaming. II. Lo- pes, Maria Immacolata Vassallo de. III. Gómez, Guillermo Orozco. CDU: 654.19 659.3 CDD: 301.161 791.445 Direitos desta edição adquiridos por Globo Comunicação e Participações S.A. -

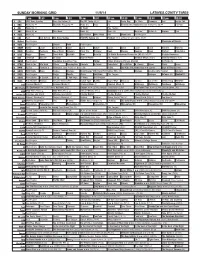

Sunday Morning Grid 11/9/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/9/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Lucky Dog Dr. Chris Changers Paid Inside Edit. 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Paid F1 Formula One Racing Brazilian Grand Prix. (N) Å F1 Post 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Explore Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football 49ers at New Orleans Saints. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Chronicles of Narnia 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å Healthy Hormones 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Brasil. -

El Rol De La Mujer Migrante En Familias Transnacionales Monoparentales, Puebla, México – Pensilvania, EUA Durante El Periodo 2000-2016

El rol de la mujer migrante en familias transnacionales monoparentales, Puebla, México – Pensilvania, EUA durante el periodo 2000-2016. Tesis presentada por Yarazetd Graciela Mendoza Camargo para obtener el grado de MAESTRA EN ESTUDIOS DE MIGRACIÓN INTERNACIONAL Tijuana, B. C., México 2019 Agradecimientos Gracias a Dios por la vida y por cada una de las bendiciones que he recibido, así como permitirme vivir y disfrutar cada día. Por que en su infinito amor me permitió tener a mi hija Aysel, quien es la mayor alegría de mi vida, mi motor y mi fuente de inspiración para poder superarme y luchar cada día para ser mejor, hija eres mi más grande amor. A Aín, mi bebé, siempre estarás en mi corazón. A mis padres, por darme la mejor educación y por enseñarme que no hay límites y que el estudio es fundamental para el crecimiento del ser humano en el mundo actual. En especial a mi padre por ser un ejemplo a seguir y creer siempre en mí, porque con su paciencia y amor siempre estuvo pendiente de mis estudios y me motivó a alcanzar mis anhelos, por enseñarme a ser tenaz y entregada a mis metas, por todo su amor y paciencia. Se que desde el cielo estás orgulloso de mi. A mi amado esposo, por su sacrificio y esfuerzo por darnos un mejor presente y futuro, por ser incondicional y apoyar siempre mis proyectos, por su amor y cariño, porque en momentos difíciles siempre ha estado para brindarme su mano y su hombro para apoyarme. Te amo, eres parte importante de este logro profesional.