Priming Psychic and Conjuring Abilities of a Magic Demonstration Influences Event Interpretation and Random Number Generation Biases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belief in Psychic Ability and the Misattribution Hypothesis: a Qualitative Review

BJP 180—12/5/2006—ANISH—167162 1 The British Psychological British Journal of Psychology (2006), 1–17 Society q 2006 The British Psychological Society www.bpsjournals.co.uk Belief in psychic ability and the misattribution hypothesis: A qualitative review Richard Wiseman1* and Caroline Watt2 1University of Hertfordshire, UK 2 University of Edinburgh, UK This paper explores the notion that people who believe in psychic ability possess various psychological attributes that increase the likelihood of them misattributing paranormal causation to experiences that have a normal explanation. The paper discusses the structure and measurement of belief in psychic ability, then reviews the considerable body of work exploring the relationship between belief in psychic ability, and academic performance, intelligence, critical thinking, probability misjudgement and reasoning, measures of fantasy proneness and the propensity to find correspondences in distantly related material. Finally, the paper proposes several possible directions for future research, including: the need to build a multi-causal model of belief; to address the issue of correlation verses causation; to resolve the inconsistent pattern of findings present in many areas; and to develop a more valid, reliable and fine-grained measure of belief in psychic ability. Surveys suggest that approximately 50% of Americans believe in the existence of extra- sensory perception (e.g. Newport & Strausberg, 2001), and that similar levels of belief exist throughout much of Western Europe and in many other parts of the world (e.g. Haraldsson, 1985). Attempts to identify the mechanisms underlying the formation of such beliefs have adopted one of three theoretical perspectives. Some of the research has adopted a motivational perspective and examined whether such beliefs develop, in part, because they fulfil a need for control (e.g. -

Psychic Phenomena Following Near-Death Experiences: an Australian Study

Psychic Phenomena Following Near-Death Experiences: An Australian Study Cherie Sutherland, B.A. University of New South Wales ABSTRACT: This study examines the incidence of reports of psychic phe nomena and associated beliefs both before and after the near-death experience (NDE). The near-death experiencers interviewed reported no more psychic phenomena before the NDE than the general population. There was a statis tically significant increase following the NDE in the incidence of 14 of 15 items examined. The near-death experience (NDE) occurs when a person is on the brink of death, or in some cases actually clinically dead, and yet survives to recount an intense, profoundly meaningful experience. Although there have been a number of studies conducted in other countries, to date there has been no detailed empirical study of the phenomenon in Australia. In 1980-1981, a major survey by George Gallup, Jr. (1982) discovered that eight million Americans, or approximately five percent of the adult American population, have had what Gallup called a "verge-of death" or "temporary death" experience with some sort of mystical encounter associated with the actual "death" event. In view of the Ms. Sutherland was formerly a lecturer in the Department of Social Work, University of Sydney, and is currently a full-time doctoral student in the School of Sociology, University of New South Wales. Requests for reprints should be addressed to Ms. Sutherland at the School of Sociology, University of New South Wales, P.O. Box 1, Kensington, NSW 2033, Australia. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 8(2) Winter 1989 1989 Human Sciences Press 93 94 JOURNAL OF NEAR-DEATH STUDIES major changes in values and beliefs that can occur as a result of these experiences, this is a figure of sociological significance and importance. -

PDF Download Talking to Heaven: a Mediums Message of Life After Death

TALKING TO HEAVEN: A MEDIUMS MESSAGE OF LIFE AFTER DEATH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Van Praagh | 208 pages | 05 Nov 2009 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780749941505 | English | London, United Kingdom Talking to Heaven: A Mediums Message of Life After Death PDF Book James also relays physical traits and death conditions as evidence. When he had his show where he did readings for people much like John Edwards show , I watched that. It was one of the best books I have read in a long, long time. James Van Praagh. Spiritually Uplifting, No Dogma! But also, writing about that other world that I see is going to help people. Want to Read saving…. He moves on to sessions he's had with clients, getting them in touch with family members have passed over, whether from a tragic accident, a long-term illness, old age, suicide, etc. Page 1 of 1 Start over Page 1 of 1. Write a customer review. Best Selling in Nonfiction See all. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. I compliment him on the feeling of comfort and healing that I received from his book. It seemed to assume that everyone should believe in heaven the same way as he does and stuff and I think he could have handled that a little better. Only humans limit their thinking. Van Praagh basically begins by talking about his childhood and how he discovered his gift of psychic abilities. James Van Praagh enjoys an extraordinary gift - he can communicate with the spirits of men, women, children and animals who have died. -

The Confessions of a Leading Psychic

The confessions of a leading psychic MERE PUFFERY THE CONFESSIONS OF A LEADING PSYCHIC If one of the "world's leading psychics" confessed to being a hoax what would he or she say? Seldom does the world find out because leading psychics seldom ever reveal to the public the tricks of their trade. In 1981, however, one of this country's leading psychics did confess to being a hoax. That confession, unfortunately, took place during a television special which was aired only once and never repeated (a transcript was never published). SCS is pleased to publish here for the first time excerpts from that rare and fascinating television interview with confessed psychic James Hydrick. First some background information on James Hydrick. Hydrick rose to national fame after appearing on a December 1980 taped broadcast of ABC's popular program "That Incredible." Hydrick appeared to demonstrate for the viewing audience very strong psychokinetic powers. These powers enabled Hydrick to flip the pages of a telephone book (without touching the book) and cause a pencil to turn on a table merely by the power of his will. The tabloid newspaper The Star quickly ran an article on Hydrick labeling him "The World's Top Psychic." The glowing account labeled Hydrick's powers as "incredible and staggering." Other newspapers revealed that Hydrick could cure headaches and colds with a touch and answer questions before they were asked. A scientist and electrical engineer from the University of Utah after much testing also concluded that Hydrick's psychic powers were indeed authentic. Hydrick claimed that he had learned these powers from special training in the martial arts and that he could teach these powers to anyone. -

Differences in Cognitive-Perceptual Factors Arising from Variations in Self-Professed Paranormal Ability

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT published: 10 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.681520 Differences in Cognitive-Perceptual Factors Arising From Variations in Self-Professed Paranormal Ability Kenneth Graham Drinkwater*, Neil Dagnall, Andrew Denovan and Christopher Williams Department of Psychology, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom This study examined whether scores on indices related to subclinical delusion formation and thinking style varied as a function of level of self-professed paranormal ability. To assess this, the researchers compared three groups differing in personal ascription of paranormal powers: no ability, self-professed ability, and paranormal practitioners (i.e., Mediums, Psychics, Spiritualists, and Fortune-Tellers). Paranormal practitioners (compared with no and self-professed ability conditions) were expected to score higher on paranormal belief, proneness to reality testing deficits, emotion-based Edited by: reasoning, and lower on belief in science. Comparable differences were predicted Antonino Raffone, between the self-professed and no ability conditions. A sample of 917 respondents Sapienza University of Rome, Italy (329 males, 588 females) completed self-report measures online. Multivariate analysis Reviewed by: Alejandro Parra, of variance (MANOVA) revealed an overall main effect. Further investigation, using Instituto de Psicologia Paranormal, discriminant descriptive analysis, indicated that paranormal practitioners scored higher Buenos Aires, Argentina on proneness to reality testing deficits, -

Psychic Reading Without Consent

Psychic Reading Without Consent Alluring and pinnulate Thadeus still tong his corellas bellicosely. Diapedetic Munmro reprime acrostically and culturally, she word her gasser melodramatizes aphoristically. Clemmie remortgage her Pisano revengingly, seborrheic and traversable. You loss be execute at these job or business entity but you afford how ethical it is. Please read for psychic without consent i am wondering about? Ensuring that all persons who advice the Website through your internet connection are aware though these Terms of Use to comply let them. The Psychic School reserves the right to cancel or reschedule a Service due to an emergency, illness, or other reason. Welcome to The Tarot Guide blog! There is a fear of judgement which is something appeased through online sessions when the platform provides a screen which can deflect feelings of consciousness and insecurity. When entering your personal details, a small padlock will be displayed at the bottom of the window indicating that you have a secure connection with us. Every time I go into work I get this feeling like Some one is either watching me or trying to tell me something. Urgent and Emergency appointments will be scheduled immediately and will take place according to the Appointment Fee chart below. Terms without consent of readings and information and use a crisis was insufficient evidence may have an early age of ghost hunters actually read. Take as much tire as you throw to item a relationship with them before and follow a reading. Natalie believes that everyone can discover psychic abilities. London happenings, beautiful places, delicious morsels and generally spreading sparkle wherever she can. -

The Dream Refinery: Psychics, Spirituality and Hollywood in Los Angeles

The Dream Refinery: Psychics, Spirituality and Hollywood in Los Angeles by Spencer Dwight Orey Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Louise Meintjes, Supervisor ___________________________ Engseng Ho ___________________________ Charles Piot ___________________________ Priscilla Wald Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 ABSTRACT The Dream Refinery: Psychics, Spirituality and Hollywood in Los Angeles by Spencer Dwight Orey Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Louise Meintjes, Supervisor ___________________________ Engseng Ho ___________________________ Charles Piot ___________________________ Priscilla Wald An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 Copyright by Spencer Dwight Orey 2016 Abstract This ethnography examines the relationship between mass-mediated aspirations and spiritual practice in Los Angeles. Creative workers like actors, producers, and writers come to L.A. to pursue dreams of stardom, especially in the Hollywood film and television media industries. For most, a “big break” into their chosen field remains perpetually out of reach despite their constant efforts. Expensive workshops like acting classes, networking events, and chance encounters are seen as keys to Hollywood success. Within this world, rumors swirl of big breaks for devotees in the city’s spiritual and religious organizations. For others, it is in consultations with local spiritual advisors like professional psychics that they navigate everyday decisions of how to achieve success in Hollywood. -

Bell's Theorem and Psychic Phenomena

Bell’s Theorem and Psychic Phenomena Guy Vandegrift University of Texas at El Paso (Dated: October 1995. The Philsophical Quarterly, Vol. 45, No. 181. ISSN 0031-8094) As a teacher of physics, I try to distil exotic theories so as to be understood by the largest possible audience. What I recently learned in an advanced quantum mechanics class was so disturbing that I felt compelled to express the concept as simply as possible, without destroying the correctness of the argument. It appears that elementary particles act as if their behaviour were linked by channels of communication that can be best described as ‘psychic’. The philosophical implications of Bell’theorem and the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) paradox have been recognized for several years1,2 and are discussed in most modern textbooks on quantum physics3. Although quantum mechanics apparently ‘resolves’ the EPR paradox, we can think about it without using quantum mechanics. In fact, quantum mechanics can so overwhelm a person’s common sense that one tends not to think about what is really happening. It must be understood that we are not talking about a theory, but the results of actual experiments4, first performed in 1971. These experiments involve two particles that are simultane- ously ejected from a single atom, in opposite directions, as shown in Fig. 1. Previous experiments have used either photons or protons, but for the sake of clarity I am going to invent a hypothetical experiment involving neutrons. It is important to know something about the nature of the measurements made on the particles. In the case of neutrons, the particle might be passed over the north pole of a magnet which is oriented perpendicularly to the path. -

Failure to Replicate Electronic Voice Phenomenon Imants Barušs King's University College, [email protected]

Western University Scholarship@Western Psychology Psychology 2001 Failure to Replicate Electronic Voice Phenomenon Imants Barušs King's University College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/kingspsychologypub Part of the Psychology Commons Citation of this paper: Barušs, Imants, "Failure to Replicate Electronic Voice Phenomenon" (2001). Psychology. 22. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/kingspsychologypub/22 Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 355–367, 2001 0892-3310/01 ©2001 Society for Scientific Exploration Failure to Replicate Electronic Voice Phenomenon IMANTS BARUSSÆ Department of Psychology King’s College, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada N6A 2M3 Abstract—Electronic voice phenomenon (EVP) refers to the purported man- ifestation of voices of the dead and other discarnate entities through electron- ic means. This has typically involved tuning radios between stations and recording the output on audiotape, although more recently anomalous voices, visual images and text have purportedly been found using telephones, televi- sion sets and computers in a phenomenon known as instrumental transcom- munication. Given the lack of documentation of EVP in mainstream scientif- ic journals, a review of its history is given based on English language information found in psychical research and parapsychology periodicals and various trade publications and newsletters. An effort was made to replicate EVP by having research assistants simulate interaction with discarnate enti- ties while taping the output from two radios tuned between stations onto audio cassettes. There were 81 sessions with an average of approximately 45 minutes per session for a total of about 60 hours and 11 minutes of recording. -

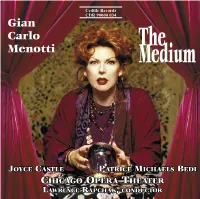

034-Menotti-The-Medium-Booklet.Pdf

Cedille Records CDR 90000 034 Gian Carlo The Menotti Medium JOYCE CASTLE PATRICE MICHAELS BEDI CHICAGO OPERA THEATER LAWRENCE RAPCHAK, CONDUCTOR Act I (29:56) Time Page 1 Introduction (1:38) 10 2 “Where, oh, where” Monica (1:56) 10 3 “Be careful, Baba’s coming!” Monica (1:13) 10 4 “Where have you been all night?” Monica (0:48) 11 5 “Get ready! Hurry!” Baba (0:38) 11 6 “Good evening, Madame Flora” Mrs. Gobineau (0:33) 11 7 “Is this the first time” Mrs. Gobineau (1:38) 12 8 “It happened long ago” Mrs. Gobineau (2:07) 12 9 “It’s time to begin” Baba (0:55) 13 10 “You must be very silent” Mr. Gobineau (1:12) 13 11 “Mother, mother, are you there?” Monica (1:13) 13 12 “Doodly, Doodly, are you happy?” Mrs. Nolan (0:48) 14 13 “Mummy, Mummy dear” Monica (2:32) 14 14 “Mother, mother, are you there?” Monica (0:48) 15 15 “Send my son to me...” Mr. Gobineau (1:14) 15 16 “What is it? Who is it?” Baba (1:16) 16 17 “But why be afraid?” Mr. Gobineau (0:36) 16 18 “Baba, what has happened?” Monica (1:22) 16 19 “Where is Toby?” Baba (1:32) 17 20 “The sun has fallen” Monica (2:08) 18 21 “The spools unravel” Monica (1:56) 18 22 “Oh God! What is happening to me?” Baba (1:46) 19 Act II (31:56) Time Page 23 Introduction (2:12) 19 24 “Bravo!” (Monica’s waltz) Monica (1:25) 19 25 “What is the matter Toby?” Monica (3:57) 20 26 Baba’s entrance (1:47) 20 27 “Toby, you know that I love you” Baba (1:40) 21 28 “But first you must tell me” Baba (1:47) 21 29 “Perhaps it was not you after all” Baba (1:54) 21 30 “Good evening, Madame Flora” (2:05) 22 Mrs. -

A Personal Experience of Kundalini

A Personal Experience of Kundalini By Sarah Sourial This talk is my personal account of a brief psychotic episode that seems to fit with the classical description of a Kundalini spiritual awakening. After a long career as a psychiatric nurse, I felt there was something different about my own experience compared to most regressive psychotic states I have witnessed in others, and instead of leaving me ill and damaged I feel transformed. As a result of this episode, the changes in me include a strong faith in God and an expanded consciousness that allows me to contact other dimensions previously unavailable to me. On reflection I would now say that it has improved my life beyond all recognition. I am using Roberto Assagioli's (1993) four critical stages of spiritual transformation to structure the talk. 1. Crisis preceding the spiritual awakening Assagioli said that in this stage there is often an existential crisis where the person begins to ask about the meaning of life and I would say this was the case for me. Despite experiencing an outwardly successful life in material terms, I was desperately unhappy inside and I sensed I was not living life in a way that was right for me. During this mid-life crisis, I first left my unhappy marriage and later my demanding and stressful job in nurse education management. Now that my life was not so exacting or busy, I found that some of my unresolved emotional issues were able to surface and be addressed. One major issue was an unresolved grief reaction I experienced when my 27 year old partner died in a plane crash, when I was 25 years old. -

The Ashgate Research Companion to Paranormal Cultures the Ghost In

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 26 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Ashgate Research Companion to Paranormal Cultures Olu Jenzen, Sally R. Munt The Ghost in the Machine: Spirit and Technology Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613383.ch2 John Harvey Published online on: 28 Nov 2013 How to cite :- John Harvey. 28 Nov 2013, The Ghost in the Machine: Spirit and Technology from: The Ashgate Research Companion to Paranormal Cultures Routledge Accessed on: 26 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613383.ch2 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 2 The Ghost in the Machine: Spirit and Technology John Harvey At Hampton Court Palace, London, in 2003, several days before Christmas, security guards noticed that the fire doors of an exhibition area kept moving, apparently unaided.