Conservation Action Planning June 2015 Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Australia's National Parks Guide

SOUTH AUSTRALIA’S NATIONAL PARKS GUIDE Explore some of South Australia’s most inspirational places INTRODUCTION Generations of South Australians and visitors to our State cherish memories of our national parks. From camping with family and friends in the iconic Flinders Ranges, picnicking at popular Adelaide parks such as Belair National Park or fishing and swimming along our long and winding coast, there are countless opportunities to connect with nature and discover landscapes of both natural and cultural significance. South Australia’s parks make an important contribution to the economic development of the State through nature- based tourism, recreation and biodiversity. They also contribute to the healthy lifestyles we as a community enjoy and they are cornerstones of our efforts to conserve South Australia’s native plants and animals. In recognition of the importance of our parks, the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources is enhancing experiences for visitors, such as improving park infrastructure and providing opportunities for volunteers to contribute to conservation efforts. It is important that we all continue to celebrate South Australia’s parks and recognise the contribution that people make to conservation. Helping achieve that vision is the fun part – all you need to do is visit a park and take advantage of all it has to offer. Hon lan Hunter MLC Minister for Sustainability, Environment and Conservation CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION FOR PARKS VISITORS ................11 Park categories.......................................................................11 -

Released Under Foi

File 2018/15258/01 – Document 001 Applicant Name Applicant Type Summary All briefing minutes prepared for Ministers (and ministerial staff), the Premier (and staff) and/or Deputy Premier (and staff) in respect of the Riverbank precinct for the period 2010 to Vickie Chapman MP MP present Total patronage at Millswood Station, and Wayville Station (individually) for each day from 1 Corey Wingard MP October 30 November inclusive Copies of all documents held by DPTI regarding the proposal to shift a government agency to Steven Marshall MP Port Adelaide created from 2013 to present The total annual funding spent on the Recreation and Sport Traineeship Incentive Program Tim Whetstone MP and the number of students and employers utilising this program since its inception A copy of all reports or modelling for the establishment of an indoor multi‐sports facility in Tim Whetstone MP South Australia All traffic count and maintenance reports for timber hulled ferries along the River Murray in Tim Whetstone MP South Australia from 1 January 2011 to 1 June 2015 Corey Wingard MP Vision of rail car colliding with the catenary and the previous pass on the down track Rob Brokenshire MLC MP Speed limit on SE freeway during a time frame in September 2014 Request a copy of the final report/independent planning assessment undertaken into the Hills Face Zone. I believe the former Planning Minister, the Hon Paul Holloway MLC commissioned Steven Griffiths MP MP the report in 2010 All submissions and correspondence, from the 2013/14 and 2014/15 financial years -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

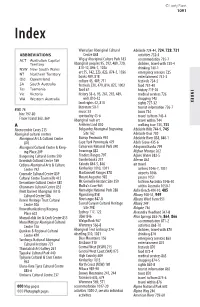

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

To Papers and Petitions 2002

Parliament of South Australia HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY INDEX TO PAPERS AND PETITIONS 2002 Final First Session, Fiftieth Parliament All inquiries relating to papers and petitions in this Index to — Bills & Papers Office, House of Assembly, Parliament House, North Terrace Adelaide 5000 Tel 8237 9384 or 8237 9206— Fax 8237 9213 Email [email protected] Papers Published Date V & P Paper No Tabled Page No A Ageing, Office of— Report, 2000-2001 PP144 05.03.02 8 Committees - Legislative Review - Ombudsman (Private or Corporatised Community PP246 05.03.02 6 Service Providers Amendment Bill ) - Report Public Works - l63' Report — Bresagen Limited — New Laboratory and PP254 05.03.02 6 Office Facilities — Final Report 164th Report — Port River Expressway — Stage One — PP255 05.03.02 6 Final Report 165th Report — Victor harbor Wastewater Treatment Plant P256 05.03.02 6 and Reuse Scheme — Final Report t1i 166 Report — TransAdelaide Resleepering Program — PP257 05.03.02 6 Final Report 167th Report — Adelaide to Darwin Railway Project — PP180 05.03.02 6 Final Report 168th Report — Old Treasury Building Redevelopment — PP181 05.03.02 6 Interim Report 169th Report — Government Radio Network Contract — PP182 05.0302 6 Status Report 170th Report — Streaky Bay Water Supply Augmentation PP183 05.03.02 6 Project — Final Report 171 st Report — South East Rail Network — Final Report PP184 05.03.02 6 72nd Report — North Terrace Redevelopment — Stage PP185 05.03.02 6 One — Interim Report 173rd Report — Central Power Station Anangu PP186 05.03.02 6 Pitjantjatjara -

State Budget 2003

Table of Contents VOLUME ONE Introduction Portfolio – Premier And Cabinet .........................................................................................................1 Portfolio – Business, Investment And Trade ......................................................................................2 Portfolio – Treasury And Finance........................................................................................................3 Portfolio–Justice...................................................................................................................................4 Accounting Standards VOLUME TWO Introduction Portfolio – Primary Industries And Resources ...................................................................................5 Portfolio – Administrative And Information Services........................................................................6 Portfolio – Human Services...................................................................................................................7 Portfolio – Education And Children’s Services...................................................................................8 Accounting Standard VOLUME THREE Introduction Portfolio – Environment And Conservation And The River Murray...............................................9 Portfolio – Transport And Urban Planning ......................................................................................10 Portfolio – Further Education, Employment, Science And Technology.........................................11 -

Regional Visitor Strategy

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN REGIONAL VISITOR STRATEGY 2025 Realising the potential of the regional visitor economy by 2025 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY South Australia’s Regional Tourism Organisation’s, the South Australian Tourism Commission, and their collective stakeholders acknowledge Aboriginal people as the First People and Nations of the lands and waters we live and work upon. We pay our respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge and respect the deep spiritual connection and relationship Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have to Country. PUBLISHED FEBRUARY 2021 Contents Introduction Regional response priorities Message from the Chair ....................................3 Adelaide Hills ............................................... 32 Message from the Premier ................................ 4 Barossa ........................................................ 35 Executive summary ......................................... 6 Clare Valley .................................................. 38 Regional Visitor Strategy 2020 Eyre Peninsula .............................................. 41 - what we achieved together ..............................9 Fleurieu Peninsula ......................................... 44 COVID-19 and natural disaster impact ............ 10 Flinders Ranges and Outback ......................... 47 What is the visitor economy? .......................... 12 Kangaroo Island ............................................ 50 South Australian 2030 Visitor Economy Sector Plan ................................................... -

Patricia Palmer Lee PRG 1722 Special List POSTCARDS INDEX

___________________________________________________________ ______________________ Patricia Palmer Lee PRG 1722 Special List POSTCARDS INDEX 1993 to 2014 NO. DATE SUBJECT POSTMARK STAMPS A1 05.07.1993 Ramsgate Beach, Botany Bay Sydney Parma Wallaby A2 09.07.1993 Bondi Beach Surf Eastern Suburbs Ghost Bat A3 13.07.1993 Autumn Foliage, Blue Mountains Eastern Suburbs Tasmanian Herit Train A4 20.07.1993 Baha'i Temple, Ingleside Eastern Suburbs Silver City Comet A5 27.07.1993 Harbour Bridge from McMahon's Point Eastern Suburbs Kuranda Tourist Train A6 04.08.1993 Winter Sunset, Cooks River, Tempe Eastern Suburbs Long-tailed Dunnart A7 10.08.1993 Henry Lawson Memorial, Domain Eastern Suburbs Little Pygmy-Possum A8 17.08.1993 Berry Island, Parramatta River Rushcutters Bay Ghost Bat A9 24.08.1993 Story Bridge, Brisbane River Eastern Suburbs Parma Wallaby A10 28.08.1993 Stradbroke Island, Moreton Bay Qld Cootamundra Long-tailed Dunnart A11 31.08.1993 Rainforest, Brisbane Botanical Gardens Yass Little Pygmy-Possum A12 05.09.1993 Dinosaur Exhibit, Brisbane Museum Eastern Suburbs Ghost Bat A13 10.09.1993 Wattle Festival Time, Cootamundra Eastern Suburbs Squirrel Glider A14 14.09.1993 Davidson Nat Park, Middle Harbour Eastern Suburbs Dusky Hopping-Mouse A15 17.09.1993 Cooma Cottage, Yass Eastern Suburbs Parma Wallaby A16 21.09.1993 Bicentennial Park, Homebush Bay Eastern Suburbs The Ghan A17 24.09.1993 Rainbow, North Coast NSW Eastern Suburbs Long-Tailed Dunnart A18 28.09.1993 Sphinx Monument, Kuring-gai Chase NP Canberra Little Pygmy-Possum A19 01.10.1993 -

Regional Workshops and Webinar Results

1 HERITAGE TOURISM: DEVELOPING A STRATEGIC DIRECTION – ENGAGEMENT REPORT Additional data report 3: Regional Workshops & Webinar Raw Results Introduction There is significant potential to unlock South Australia’s heritage places and stories to create experiences that showcase our state’s distinctive history, enhance the appeal of South Australia, and encourage visitors to stay longer and spend more. In September and October 2019, the Government sought input from those involved in the tourism industry and heritage sector to help develop a strategy and action plan that maximises the economic value of heritage and contributes to growing the South Australian visitor economy to $12.8 billion by 2030. Tourism industry, heritage operators and custodians, local government, regional communities, Traditional Owners, and those with an interest in heritage tourism were invited to share views and ideas on growing heritage tourism in South Australia by: Attending a small-group workshop or webinar Participating in an online discussion Completing an in-depth online questionnaire Emailing a written submission This report provides raw data collected through 16 regional workshops and one webinar held between 10 and 30 September. Workshop & webinar details The workshops and webinar were delivered by staff from the Department of Environment and Water following a structure developed by IPS Management Consultants, and in partnership with the Tourism Industry Council of South Australia. Workshops were held in the following locations: Region Date Location -

SOUTH AUSTRALIA 南澳大利亚州 TUESDAY 23 JUNE Webinar #1 南澳大利亚旅游概述和新产品介绍

An Overview of SOUTH AUSTRALIA 南澳大利亚州 TUESDAY 23 JUNE Webinar #1 南澳大利亚旅游概述和新产品介绍 TUESDAY 30 JUNE Webinar #2 南澳大利亚经典自驾线路 Road Trips TUESDAY 07 JULY Webinar #3 阿德莱德&山区,芭萝莎和袋鼠岛 TUESDAY 14 JULY Webinar #4 石灰岩海岸,菲尔半岛和艾尔半岛 TUESDAY 21 JULY Webinar #5 南澳特色主题线路设计(高端/户外/亲子/游学/ 美食美酒等) TUESDAY 28 JULY Webinar #6 南澳本地华人旅行社合作产品培训介绍 DOMESTIC FLIGHTS INTO ADELAIDE WHY SOUTH AUSTRALIA ? |南澳旅游的独特卖点 精致文艺便利的 天然环境中的野 旅游景点体验都 南澳自然奇境 世界级美食美酒 阿德莱德 生动物体验 在1-2小时车程, 旅游效率高 Accessible Provenance ADELAIDE 阿德莱德 关键词:精致,复古,文艺,便利 关于阿德莱德| FAST FACTS • 阿德莱德机场至市区仅需15分 钟车程 • 市区呈平坦正方形,方便步行 • 市区内有轨电车免费乘坐 • 15分钟车程至海边沙滩,公交 电车可以直达 • 20分钟车程至东面阿德莱德山 区 EOS by SKYCITY Riverbank, North Terrace 房间类型: 123 间豪华套房 六星酒店. VIP 套房, 阿德莱德 具体类型: 赌场酒店,娱乐区,桑拿Spa 楼顶游泳池. 修建进度: 正在兴建中 预计完工时间: 2020年末 联系方式: 点击这里 ADELAIDE OVAL HOTEL Adelaide ROOMS: 138 个房间 四星级,阿德莱德椭圆形体育 DETAILS: 场东面的6层楼建筑 STATUS: 正在修建中 OPEN: 2020年10月 联系方式: 点击这里 CROWNE PLAZA HOTEL Frome Street, 阿德莱德市区 ROOMS: 329 个豪华房间 DETAILS: 4.5星,阿德莱德最高建筑34层 STATUS: 正在修建中 OPENING: 2020年10月 HOTEL INDIGO 英迪格酒店 Market Street ROOMS: 137 间古典精致房间 4星潮系酒店,阿德莱德中央 市场隔壁,健身房,屋顶泳池, DETAILS: IHG酒店集团在澳大利亚的新 酒店品牌系列。 STATUS: 正在修建中 OPENING: 2020年底 SOFITEL HOTEL Currie Street,Adelaide ROOMS: 251个豪华房间 五星酒店32层楼高.包含 69个 DETAILS: 酒店公寓,餐厅,4个酒吧, 会议中心,台球室,游泳池. STATUS: 修建中 COMPLETION: 2020年末 WESTIN HOTEL Victoria Square,Adelaide ROOMS: 285个豪华房间 在历史建筑上修建的五星酒店 DETAILS: 市中心主干道King William Street/Franklin Street之间 正在进行中 STATUS: Preparation of site COMPLETION: 2021年底完工 FOOD TOURS AUSTRALIA • 阿德莱德中央市场Central Market • 参观澳大利亚最有名的市场,150多年悠久历史 • 小团出发 • 新的适合澳州境内客人的产品,有中文tour • 品尝南澳当地本土特色食材和精华店铺试吃 -

ADELAIDE to ERLDUNDA: STUART HIGHWAY © Lonelyplanetpublications Springs, Thegargantuan Eyre Lake Andsomeamazingoldoutbackpubs

© Lonely Planet Publications 130 Adelaide to Erldunda: STUART HIGHWAY STUART HIGHWAY Stuart Highway ADELAIDE TO ERLDUNDA: ADELAIDE TO ERLDUNDA: No doubt about it: the Adelaide-to-Darwin drive up the middle of central Australia is a classic Australian road trip. The South Australian leg starts with a seductive swing through the vineyards of the Clare Valley, then a dash up Hwy 1 to Port Augusta, from where the Stuart Hwy shoots gun-barrel straight into the desert. Far less commercial and brassy than the Barossa Valley further south, the Clare Valley pro- duces some of the world’s best Riesling. Here in the Mid North – perhaps South Australia’s most underrated region – charismatic sandstone villages crop up unexpectedly among rounded hills, patchwork wheaten plains, tilled fields and ranks of grapevines under the sun. Back on Hwy 1, Port Augusta squats at the base of the Flinders Ranges, looking optimistically at the highway and wondering if anyone’s going to stop today. In fact, someone usually does – the ‘Crossroads of Australia’ has become a busy conference venue, with more motels than you can poke a pillow at. The town’s revitalised Spencer Gulf waterfront is an added drawcard. But what this chapter (and indeed this book) is really about is the Big Drive North. Head- ing into the red heart of Australia on the Stuart Hwy, Woomera is the first pit stop, with its dark legacy of nuclear tests and shiny collection of leftover rockets. Further north, the opal-mining town of Coober Pedy is an absolute one-off: a desolate human aberration amid the blistering, arid plains. -

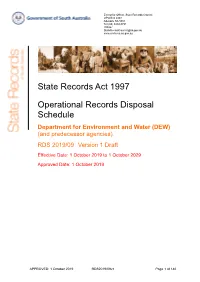

(DEW) (And Predecessor Agencies) RDS 2019/09 Version 1 Draft Effective Date: 1 October 2019 to 1 October 2029 Approved Date: 1 October 2019

Executive Officer, State Records Council GPO Box 2343 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (08) 8204 8791 DX467 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au State Records Act 1997 Operational Records Disposal Schedule Department for Environment and Water (DEW) (and predecessor agencies) RDS 2019/09 Version 1 Draft Effective Date: 1 October 2019 to 1 October 2029 Approved Date: 1 October 2019 APPROVED: 1 October 2019 RDS2019/09v1 Page 1 of 146 Operational Records Disposal Schedule RDS 2019/09 Version 1 Effective Date: 1 October 2019 to 1 October 2029 Department for Environment and Water (and predecessor agencies or functions) Table of Contents Preamble .............................................................................................................................. 4 Purpose of the Schedule ................................................................................................... 4 Application of the Schedule ............................................................................................... 4 Authorisation by State Records ......................................................................................... 4 State Records’ Contact Information ................................................................................... 4 Disposal of Official Records .................................................................................................. 5 Legislation ......................................................................................................................... 5 Functions of the Schedule -

Christmas Opening Hours

NEWS RELEASE 19/12/14 MEDIA CONTACT Jill Freear Christmas opening hours Senior Media Advisor Department of Environment, A number of sites managed by the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Water and Natural Resources Resources will have amended opening hours over the Christmas and New Year period. Phone (08) 8463 7412 Adelaide Botanic Garden: Open every day, with shortened hours of 9am to 7pm on public Mobile 0428 046 360 Email [email protected] holidays. Adelaide Gaol: Closed Christmas Day and 31 December to 2 January. The New Building, www.environment.sa.gov.au including the hanging chamber, will be closed on 30 December. www.nrm.sa.gov.au Cleland Wildlife Park: Closed Christmas Day and on days of catastrophic fire danger. DEWNR Customer Service Centre (Pirie Street, Adelaide): Closed 25 December to 2 January. Kelly Hill Caves: Closed Christmas Day and on days of catastrophic fire danger. Mount Lofty Botanic Garden: Open every day, with shortened hours of 10am to 5pm on public holidays. Closed on days of severe fire danger. Mount Lofty Summit Visitor Information Centre: Closed Christmas Day and on days of catastrophic fire danger. Open 9am to 5pm on New Year’s Day. Visit www.mtloftysummit.com for opening hours of the Mount Lofty Summit Restaurant. Naracoorte Caves: Closed Christmas Day and on days of catastrophic fire danger. Extended trading hours in the Caves Café over summer. Visit www.naracoortecaves.sa.gov.au for details. Tantanoola Caves: Closed Christmas Day and on days of catastrophic fire danger. Seal Bay: Closed Christmas Day and on days of catastrophic fire danger.