Nitrate Tmdl Development: the Muddy Creek/Dry River Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

Studies of Longitudinal Stream Profiles in Virginia and Maryland

Studies of Longitudinal Stream Profiles in Virginia and Maryland By JOHN T. HACK SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL. SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 294-B Preliminary results of a study of the form of small river valleys in relation to geology. Some factors controlling the longitudinal profiles of streams are described in q'uantitative terms UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1957 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 75 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Peg* AbstractL 45 Relation of particle size of material on the bed to stream IntroductionL 47 lengthL 68 Methods of study and definitions of factors measuredL 47 Mathematical expression of the longitudinal profile and Description of areas studied L 49 its relation to particle size of material on the bedL 69 Middle River basinL 50 Mathematical expression in previous work on longitudinal North River basinL 50 profilesL 74 Alluvial terrace areasL 50 Origin and composition of stream-bed materialL 74 Calfpasture River basinL 50 Franks Mill reach of the Middle RiverL 76 Tye River basin L 52 Eidson CreekL 81 Gillis FallsL 52 East Dry BranchL 82 Coastal Plain streamsL 53 North RiverL 84 Factors determining the slope of the stream channelL 53 Calfpasture ValleyL 84 Discharge and drainage areaL 54 Gillis FallsL 85 Size of material on the stream bedL 54 Ephemeral streams in areas of residuumL 85 Channel cross sectionL 61 Some factors controlling variations in size: conclusions_ _ _ 86 Summary of factors controlling channel slopeL 61 The longitudinal profile and the cycle of erosionL 87 Factors determining the position of the channel in space: the References cited L 94 shape of the long profileL 63 IndexL 95 Relation of stream length to drainage area L 63 ILLUSTRATIONS Pag e Page PLATE99. -

GAME FISH STREAMS and RECORDS of FISHES from the POTOMAC-SHENANDOAH RIVER SYSTEM of VIRGINIA

) • GAME FISH STREAMS AND RECORDS OF FISHES FROM THE POTOMAC-SHENANDOAH RIVER SYSTEM Of VIRGINIA Robert D. Ross Associate Professor of Biology Technical Bulletin 140 April 1959 Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station Virginia Polytechnic Institute Blacksburg, Virginia ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer is grateful to Eugene S. Surber, Robert G. Martin and Jack M. Hoffman who directed the survey and gave their help and encouragement. A great deal of credit for the success of the Survey is due to all game wardens who rendered invaluable assistance. Special thanks are due to many sportsmen and assistant game wardens who helped the field crew. Personnel of the Commission of Game and Inland Fisheries, who helped in the work from time to time were William Fadley, William Hawley, Max Carpenter and Dixie L. Shumate. The Virginia Academy of Science gener- ously donated funds for the purchase of alcohol in which the fish collection was preserved. GAME FISH STREAMS AND RECORDS OF FISHES FROM THE SHENANDOAH-POTOMAC RIVER SYSTEMS OF VIRGINIA Robert D. Ross Associate Professor of Biology Virginia Polytechnic Institute INTRODUCTION From June 15 to September 15, 1956, the Commission of Game and Inland Fisheries, Division of Fisheries, Richmond, Virginia, undertook a survey of a major part of the Shenandoah-Potomac River watershed in Virginia. This work was done as Federal Aid Project No. F-8-R-3, in cooperation with Vir- ginia Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, under the direction of Robert G. Martin, Dingell-Johnson Coordinator, and Jack M. Hoffman, Leader. Robert D. Ross, Crew Leader, and David W. Robinson and Charles H. Hanson worked in the field. -

Wild and Scenic Rivers Eligibility

GEORGE WASHINGTON NATIONAL FOREST APPENDIX D – WILD AND SCENIC RIVERS ELIGIBILITY APPENDIX D – WILD AND SCENIC RIVERS ELIGIBILITY DETERMINATION The 1993 Forest Plan Revision included an extensive review and evaluation of the rivers of the George Washington National Forest. Appendix D of the 1993 Forest Plan was reviewed. The information and determinations documented in Appendix D remain valid with minor changes in conditions. Public comments did identify some additional rivers for consideration. These included Trout Run, Waites Run, Stony Creek (North of Bayse), German River, Benson Run, Stuart Run (with Buck Lick and Bolshers Run), Mill Creek (Maury River), Wilson Creek, Mill Creek (Cowpasture River), Jim Dave Run, Potts Creek, Little Back Creek, Crow Run (with Little Crow Run), and Big Mary’s. A review of these streams identified no nationally or regionally outstandingly remarkable values in recreation, scenery, wildlife, geology, botany or heritage resources. Under the fisheries resource we did identify that Potts Creek and Mill Creek provide habitat for the James spinymussel. However, in both of these cases, the location of the mussel is downstream of National Forest System lands. I. INTRODUCTION This appendix contains evaluations of 14 rivers located in or close to the George Washington National Forest. These evaluations determine which of the 14 rivers have qualities that make them eligible for inclusion in the National Wild and Scenic River System. The evaluations also determine whether the eligible rivers should receive wild, scenic, or recreational river classification. A determination locally that a river is eligible does not necessarily mean that it will meet suitability criteria when, in the final stages, it is evaluated from a national perspective. -

The Nature Conservancy's Watershed Approach To

THE NATURE CONSERVANCY’S WATERSHED APPROACH TO COMPENSATION PLANNING FOR THE VIRGINIA AQUATIC RESTORATION TRUST FUND December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE: THE NATURE CONSERVANCY’S CONSERVATION BY DESIGN .... 2 Background ..................................................................................................................... 2 The Nature Conservancy’s Conservation By Design ..................................................... 3 Element I: Geographic service area delineation ............................................................ 4 Elements ii, iii and iv: Threats Assessment ................................................................... 8 Elements v and vi: Aquatic resource goals / objectives and a prioritization strategy.. 10 Element xii. Satisfying Criteria for Use of Preservation ............................................. 13 Element viii. A description of any public and private stakeholder involvement in the plan ................................................................................................................................ 13 Element ix. Long-term protection and management strategies ................................... 15 Element x. Monitoring and Evaluating Progress .......................................................... 15 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 17 PART II. OVERVIEW OF ECOREGIONAL PRIORITY CONSERVATION AREAS BY DEQ/CORPS SERVICE AREAS ............................................................................. -

Historic Architectural Survey of Rockingham County, Virginia

HISTORIC ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY OF ROCKINGHAM COUNTY, VIRGINIA Mannheim (082-0005) FINAL REPORT Prepared by E.H.T. Traceries, Inc. for The Virginia Department of Historic Resources and Rockingham County, Virginia Department of Planning RFP No. 1999/2000-09 December 2000 HISTORIC ARCHITECTURAL SURVEY OF ROCKINGHAM COUNTY, VIRGINIA Final Report Prepared by E.H.T. Traceries, Inc. for The Virginia Department of Historic Resources and Rockingham County, Virginia Department of Planning RFP No. 1999/2000-09 (Contact: William L. Vaughn and Rhonda G. Henderson, Department of Planning 540/564-3030) December 2000 Architectural Survey Report of Rockingham County, Virginia E.H.T. Traceries, Inc., December 2000 Page ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................................................................iii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................................................. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................ vi MAPS ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

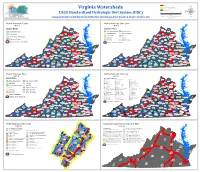

Virginia Watershed Map (PDF)

Interstate Virginia Watersheds Central Shenandoah PDC Water Features USGS Standardized Hydrologic Unit System (HUC) 0 50 100 Miles Sources: USGS, NRCS, CSPDC, and Commonwealth of VA Topographically Nested Hierarchy Defined Set of Drainage Areas based on Surface Feature Size For planning purposes only. : (May, 2011) Virginia Hydrologic Regions Virginia Hydrologic Sub-regions HUC 2 HUC 4 Region Name Frederick Subregion Name Frederick Winchester Winchester Clarke Clarke Mid Atlantic Region Loudoun Big Sandy-Guyandotte Kentucky-Licking Loudoun §¨¦495 Chowan-Roanoke Lower Chesapeake §¨¦495 Warren ¨¦§66 Arlington Warren ¨¦§66 Arlington Fairfax City Fairfax City Ohio Region Shenandoah Alexandria Shenandoah Alexandria Fairfax Cumberland Pee Dee Fairfax Fauquier Manassas City Fauquier Manassas City South Atlantic-Gulf Region Rappahannock Prince William Rappahannock Prince William Rockingham Page Delaware Potomac Rockingham Page Tennessee Region Culpeper Kanawha Upper Tennessee Culpeper Stafford Stafford Harrisonburg Madison Harrisonburg Madison Virginia Localities / Jurisdictions Highland Highland Fredericksburg King George Virginia Localities / Jurisdictions Fredericksburg King George Greene Orange Greene Orange Spotsylvania Spotsylvania Augusta Staunton Westmoreland Augusta Staunton Westmoreland Waynesboro ¨¦§95 Waynesboro ¨¦§95 Bath Albemarle Charlottesville Louisa Caroline Bath Albemarle Charlottesville Louisa Caroline Essex Richmond Essex Richmond ¨¦§64 Northumberland ¨¦§64 Northumberland Rockbridge Rockbridge 64 64 Alleghany ¨¦§ Fluvanna -

Drainage Areas of Selected Streams in Virginia

Prepared in cooperation with the Virginia Department of Transportation and the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Drainage Areas of Selected Streams in Virginia Open-File Report 2006–1308 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Drainage Areas of Selected Streams in Virginia By Donald C. Hayes and Ute Wiegand Prepared in cooperation with the Virginia Department of Transportation and the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Open-File Report 2006–1308 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Dirk A. Kempthorne, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Hayes, D.C., and Wiegand, Ute, 2006, Drainage areas of selected streams in Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey Open- File Report 2006–1308, 51 p., available online at http://pubs.water.usgs.gov/ofr2006-1308 iii Contents -

DC Source Water Assessment

The District of Columbia Source Water Assessment Environmental Health Administration Bureau of Environmental Quality Water Quality Division The District of Columbia Source Water Assessment Prepared For: Environmental Health Administration Department of Health Government of the District of Columbia Anthony A. Williams, Mayor Prepared By: David T. Vann, Ross Mandel, Jason M. Miller Erik Hagen, Anthony Buda and Daniel Cordalis Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin TABLE OF CONTENTS, LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES Table of Contents i List of Appendices iii List of Tables iii List of Figures iii Acknowledgements v Executive Summary E-1 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1-1 1.2 The Components of the Source Water Assessment 1-1 1.3 The Use of the CBP Watershed Model in the SWA 1-2 2.0 The Watershed and Drinking Water 2.1 Source Water Delineation 2-1 2.2 General Description of Source Water 2-2 2.2.1 Physiography 2.2.2 Topography 2-3 2.3 Basin Geology 2-3 2.4 Land Use 2-5 2.5 Population 2-5 2.6 General Hydrology 2-5 2.6.1 Streamflow Regulation 2-6 2.6.2 Flow Characteristics 2-6 2.7 The Drinking Water System 2-6 2.7.1 Other Greater Metro Water Systems 2-7 2.7.2 System Operations 2-7 3.0 Time of Travel Analysis 3.1 Time of Travel Analysis 3-1 3.1.1 Methods 3-1 3.1.2 Verification of Spill Model Approach Using Hydraulic Equations 3-4 4.0 Susceptibility Analysis 4.1 Potential Point Source Pollution Sites and Contaminant Inventory 4-1 4.1.1 Sources of Contaminants 4-1 4.1.2 Data Sources 4-1 4.2 Geographic Information Systems 4-2 4.2.1 Search and -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

North Fork of the Shenandoah River Watershed Assessment Virginia and West Virginia

North Fork of the Shenandoah River Watershed Assessment Virginia and West Virginia June 2008 Rapid watershed assessments provide initial estimates of where conservation investments would best address the concerns of landowners, conservation districts, and other community organizations and stakeholders. These assessments help landowners and local leaders set priorities and determine the best actions to achieve their goals. U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Richmond, Virginia "The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720- 6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer." North Fork of the Shenandoah River Watershed Assessment Virginia and West Virginia Frederick, Page, Rockingham, Shenandoah and Warren Counties, Virginia and Hardy County, West Virginia Abstract This watershed assessment involved the collection of data and information for the purpose of developing a watershed profile, including a description of the natural resource conditions and trends, issues, concerns and problems along with recommendations for local action. -

Virginia Watersheds USGS Hydrologic Unit River Systems for Use with Science Sols – 4.8, 6.7, ES9, Bio9

Virginia Watersheds USGS Hydrologic Unit River Systems For use with Science SOLs – 4.8, 6.7, ES9, Bio9 Chesapeake Bay and Mid- James Drainage: Sandy River Atlantic Region: James River Stinking River Rivanna River Turkeycock River Eastern Shore Drainage: Maury River Pocomoke River Cowpasture River Yadkin Drainage: Machipongo River Jackson River Ararat River Chincoteague River Buffalo River Piney River Ohio Region Potomac Drainage: Appomattox River Potomac River Chickahominy River New River Drainage: Shenandoah River Lynch River Knob Fork Occoquan River Roach River Laurel Fork North River Rockfish River Little River Middle River Tye River Muskrat Branch Little Wicomico River Pedlar River New River Dry River Nansemond River Tract Fork Hardware River Wolfpen Branch York Drainiage: Bullpasture River South River Big Sandy Drainage: South Anna River South Atlantic Region Cranes Nest River Po River Levisa Fork River Pamunkey River Chowan Drainage: McClure River North Anna River Warwick Branch Pound River Ni River South Meherrin River Russell Fork New Found River Nottoway River Tug River Mattaponi River North Meherrin River Little River Middle Meherrin River Tennessee Region Meherrin River Rappahannock Drainage: Little Nottoway River Holston Drainage: Western Branch Chowan River Big Moccasin Creek Corrotoman River Blackwater Swamp Holston River Ware River Blackwater River Possum Creek Thorton River Assomoosick Swamp Walker Creek Robinson River Whitetop Laurel Creek Rappahannock River Roanoke Drainage: Rapidan River Banister River Clinch Drainage: Portobago Creek Big Otter River Clinch River Pankatank River Blackwater River Guest River North Fork Thorton River Dan River Little River Massaponax River Falling River Powell River Hazel River North Mayo River Great Wicomico River Pigg River Roanoke River __________________________________ ________________________________________ Watershed information is for the following "Where Does Water Run?" Aquatic Guide pg.