Uyghur Association of Victoria (UAV)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Ii Uniqlo Company Profile and the Network in China

CHAPTER II UNIQLO COMPANY PROFILE AND THE NETWORK IN CHINA In this chapter the author will focus on the discussion of the company profile of UNIQLO as a research subject which is one of the world's leading fast fashion companies. The author wants to show how UNIQLO stands and becomes a company that is expanding globally throughout the world. The author will also explain the network of UNIQLO in China. A. UNIQLO Company History and Profile After World War II ended, precisely in 1949, was the beginning of UNIQLO establishment. At that time the company was founded by Hitoshi Yanai who is the father of the current managing director Tadashi Yanai opened a men's clothing store named Ogori Shoji in Ube City, Yamaguchi Prefecture. In 1984 precisely when Tadashi Yanai was an adult, he founded a shop that sells casual clothing under the name Unique Clothing Warehouse in Hiroshima City.30 The name "UNIQLO" itself arises from the combination of the words "Unique Clothing". The main aim of the UNIQLO company is to inspire the world by casual dress. In taking the name UNIQLO, the company has the brand philosophy "Made for All" as the company's slogan. In 1991 Tadashi Yanai changed the name of his father's company "Ogori Shōji" to "Fast Retailing". 30 Staff abyad apparel pro. (2019, September 3). Sejarah Tentang Uniqlo Dan Perkembangannya Di Indonesia. Retrieved From Abyad Apparel Pro: http://abyadscreenprinting.com/sejarah-uniqlo-dan- perkembangannya/ 18 2.1The First UNIQLO Store Before the 1990s, UNIQLO was not a product known to the wider community, Japanese people tended to see well-known brands and of course that could elevate their prestige. -

Download the Covid Fashion Report

E H T COVID FASHION REPORT A 2020 SPECIAL EDITION OF THE ETHICAL FASHION REPORT THE COVID FASHION REPORT A 2020 SPECIAL EDITION OF THE ETHICAL FASHION REPORT Date: October 2020 Australian Research Team: Peter Keegan, Chantelle Mayo, Bonnie Graham, Alexandra Turner New Zealand Research Team: Annie Newton-Jones, Claire Gray Report Design: Susanne Geppert Infographics: Susanne Geppert, Matthew Huckel Communications: Samara Linehan Behind the Barcode is a project of Baptist World Aid Australia. New Zealand headquartered companies researched in partnership with Tearfund New Zealand. www.behindthebarcode.org.au Front cover photo: KB Mpofu, ILO via Flickr CONTENTS PART ONE PART TWO PART THREE The COVID Challenge COVID Fashion Actions & Commitments Recommendations The 2020 Special Edition .......................5 1: Support Workers’ Wages by Industry Action ....................56 .... COVID Fashion Commitments ................7 Honouring Supplier Commitments 19 Consumer Action.................57 Industry Response to COVID-19 ..............8 2: Identify and Support the Workers at Greatest Risk .......... 26 COVID-19 and Garment Workers ...........10 COVID-19 and Consumers .................... 11 3: Listen to the Voices and Experience of Workers ............. 32 COVID-19 and Fashion Companies ........13 Appendices 4: Ensure Workers’ Rights Methodology .....................................14 and Safety are Respected ............... 39 Fashion Company-Brand Company Fashion Tiers .......................17 Reference List 59 5: Collaborate with Others Endnotes 64 to Protect Vulnerable Workers ......... 46 About Baptist World Aid 6: Build Back Better for Workers Australia 66 and the World ............................... 50 Acknowledgements 67 Part One THE COVID CHALLENGE THE 2020 SPECIAL EDITION 2020 has been a year like no other. COVID-19 has swept across the planet, sparking subsequent health, economic, and humanitarian crises. -

Correspondence with Uniqlo

Rt Hon Tom Tugendhat MP Rt Hon Nusrat Ghani MP Rt Hon Darren Jones MP Chair, Foreign Affairs Committee Business, Energy and Chair, Business, Energy and House of Commons Industrial Strategy Committee Industrial Strategy Committee London SW1A 0AA House of Commons House of Commons London SW1A 0AA London SW1A 0AA 23 November 2020 Dear Mr Tugendhat, Ms Ghani and Mr Jones, Thank you for your letter dated 9 November 2020 regarding UNIQLO supply chain which reportedly includes materials and labour sourced from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. UNIQLO appreciate your enquiry as we take matters of human rights and ethical responsibilities seriously. We have worked closely with the relevant sections of our business including our parent company Fast Retailing based in Japan to provide detailed responses to your questions, as follows: 1. What is the nature and extent of your company’s operations in Xinjiang? UNIQLO does not own or directly operate any factories as part of its business. Additionally, no UNIQLO product is manufactured in the Xinjiang region by any of our production partners, and none of our production partners subcontract to fabric mills or spinning mills in the region. 2. What specific raw materials arriving in UK markets are sourced from Xinjiang? UNIQLO sources sustainable cotton*1, and this includes cotton originating in China. By definition, sustainable cotton is that which ensures human rights and good working environments, in accordance with international standards. Sustainable cotton forbids the use of both forced labour and child labour at farms. *1 Sustainable cotton refers to Better Cotton*2 sources; cotton sourced from the United States or Australia, recycled cotton*3; organic cotton*4; Fair Trade cotton; and Cotton made in Africa (CmiA). -

UNIQLO Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト

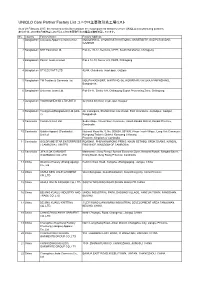

UNIQLO Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト As of 28 February 2017, the factories in this list constitute the major garment factories of core UNIQLO manufacturing partners. 本リストは、2017年2月末時点におけるユニクロ主要取引先の縫製工場を掲載しています。 No. Country Factory Name Factory Address 1 Bangladesh Colossus Apparel Limited unit 2 MOGORKHAL, CHOWRASTA NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, GAZIPUR SADAR, GAZIPUR 2 Bangladesh NHT Fashions Ltd. Plot no. 20-22, Sector-5, CEPZ, South Halishahar, Chittagong 3 Bangladesh Pacific Jeans Limited Plot # 14-19, Sector # 5, CEPZ, Chittagong 4 Bangladesh STYLECRAFT LTD 42/44, Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur 5 Bangladesh TM Textiles & Garments Ltd. MOUZA-KASHORE, WARD NO.-06, HOBIRBARI,VALUKA,MYMENSHING, Bangladesh. 6 Bangladesh Universal Jeans Ltd. Plot 09-11, Sector 6/A, Chittagong Export Processing Zone, Chittagong 7 Bangladesh YOUNGONES BD LTD UNIT-II 42 (3rd & 4th floor) Joydevpur, Gazipur 8 Bangladesh Youngones(Bangladesh) Ltd.(Unit- 24, Laxmipura, Shohid chan mia sharak, East Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur, 2) Bangladesh 9 Cambodia Cambo Unisoll Ltd. Seda village, Vihear Sour Commune, Ksach Kandal District, Kandal Province, Cambodia 10 Cambodia Golden Apparel (Cambodia) National Road No. 5, No. 005634, 001895, Phsar Trach Village, Long Vek Commune, Limited Kompong Tralarch District, Kompong Chhnang Province, Kingdom of Cambodia. 11 Cambodia GOLDFAME STAR ENTERPRISES ROAD#21, PHUM KAMPONG PRING, KHUM SETHBO, SROK SAANG, KANDAL ( CAMBODIA ) LIMITED PROVINCE, KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 12 Cambodia JIFA S.OK GARMENT Manhattan ( Svay Rieng ) Special Economic Zone, National Road#, Sangkat Bavet, (CAMBODIA) CO.,LTD Krong Bavet, Svay Rieng Province, Cambodia 13 China Okamoto Hosiery (Zhangjiagang) Renmin West Road, Yangshe, Zhangjiagang, Jiangsu, China Co., Ltd 14 China ANHUI NEW JIALE GARMENT WenChangtown, XuanZhouDistrict, XuanCheng City, Anhui Province CO.,LTD 15 China ANHUI XINLIN FASHION CO.,LTD. -

GREAT CLOTHES CAN CHANGE OUR WORLD Is a Global Company That Operates Multiple Fashion Brands Including UNIQLO, GU, and Theory

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Year ended 31 August 2018 GREAT CLOTHES CAN CHANGE OUR WORLD is a global company that operates multiple fashion brands including UNIQLO, GU, and Theory. The world’s third largest manufacturer and retailer of private-label apparel, Fast Retailing offers high-quality, reasonably priced clothing by managing everything from procurement, design, and production to retail sales. UNIQLO, our pillar brand, generates approximately ¥1.76 trillion in sales from 2,068 stores in 21 countries and regions (FY2018). UNIQLO, with its LifeWear concept of ultimate everyday comfort, differentiates itself by offering unique products such as sweaters made from superior-quality cashmere, supima cotton T-shirts, and ranges incorporating original HEATTECH and Ultra Light Down technologies. The Group’s main sources of UNIQLO-driven growth are moving beyond Japan to Greater China (Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan) and Southeast Asia. Our fun, low-priced fashion brand GU has generated sales of approximately ¥210 billion, primarily in Japan. We expect to grow the GU brand in Greater China and South Korea going forward. Fast Retailing is making progress on its Ariake Project, which aims to transform the apparel retail industry into a new digital consumer retail industry. We are working to build a supply chain that uses advanced information technology to create seamless links between Fast Retailing and its partner factories, warehouses, and stores worldwide. This transformation will minimize the environmental impact of our business, create a manufacturing environment that upholds human rights, and ensure highly responsible procurement. Fast Retailing strives to harness the power of clothing to enrich the lives of people around the world, and create a more sustainable society. -

Performance Analysis of China's Fast Fashion Clothing Market Based on SCP Model

Open Journal of Business and Management, 2019, 7, 106-115 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojbm ISSN Online: 2329-3292 ISSN Print: 2329-3284 Performance Analysis of China’s Fast Fashion Clothing Market Based on SCP Model Lu Ge1, Xuran Sun1, Chenggang Li2* 1Department of Business Administration, Fashion Brand Management, Business School of BIFT, Beijing, China 2Department of Network Economy, Electronic Business, Network Marketing, Management Innovation, Business School of BIFT, Beijing, China How to cite this paper: Ge, L., Sun, X.R. Abstract and Li, C.G. (2019) Performance Analysis of China’s Fast Fashion Clothing Market China’s fast fashion clothing market is dominated by Uniqlo, ZARA and H & Based on SCP Model. Open Journal of Busi- M, supplemented by other fast fashion clothing brands. This paper uses SCP ness and Management, 7, 106-115. paradigm to analyze the fast fashion brands in China’s clothing market. By https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2019.71007 dividing the market structure of China’s fast fashion clothing, it is concluded Received: November 15, 2018 that the market structure of China’s fast fashion clothing is oligopoly III, and Accepted: December 16, 2018 the cost oriented price behavior of enterprises in the oligopoly market struc- Published: December 19, 2018 ture is analyzed. In order to analyze the market performance of China’s fast Copyright © 2019 by authors and fashion clothing market, digital non-price behavior and organizational ad- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. justment behavior of increasing the number of stores are used to analyze the This work is licensed under the Creative market performance of China’s fast fashion clothing market. -

Celebrating Our Second Store in Illinois! 5 Woodfield Mall, Schaumburg, IL 60173 Photo Shown: UNIQLO Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL This Is Lifewear

Celebrating our second store in Illinois! 5 Woodfield Mall, Schaumburg, IL 60173 Photo shown: UNIQLO Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL This Is LifeWear Who you are, what you believe in: that’s what you wear every day. And that is what we make clothing for. Welcome to a new way of apparel. Apparel that comes from our Japanese values of simplicity, quality and longevity. Designed to be of the time and for the time. Made with such modern elegance that it becomes the building blocks of your style. A perfect shirt that is always being made more perfect. The simplest design hiding the most thoughtful and modern details. The best in fit and fabric made to be affordable and accessible to all. Clothing that we are constantly innovating, bringing more warmth, more lightness, better design, and better comfort to your life. It never stops evolving because your life never stops changing. Simple apparel with a not-so-simple purpose: to make your life better. Uniqlo LifeWear. Simple made better. Extra Fine Merino The luxurious texture and quality you’ll know MEN as soon as you touch it. Known worldwide as the Extra Fine Merino best in merino wool. Woven for warmth. V-Neck Sweater WOMEN $39.90 Extra Fine Merino Crew Neck Sweater $29.90 WOMEN 3D Extra Fine Merino Ribbed Turtleneck Long-Sleeve Dress $59.90 Made with 100% natural extra fine merino wool. Premium smoothness at first touch. Supremely soft and highly breathable, Made with ultra-fine fibers of just 19.5 microns for supreme softness and luster. Extra Fine Merino is a premium Luxurious Extra wool fabric that is also used in high-end suits. -

Woolworths Holdings Limited 2014 Integrated Report

WOOLWORTHS HOLDINGS LIMITED 2014 INTEGRATED REPORT WHILE OUR STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES ARE AIMED AT DRIVING GROWTH AND STAKEHOLDER VALUE, OUR GOOD BUSINESS JOURNEY ENSURES THAT WHAT WE DO IS RIGHT, BOTH SOCIALLY AND ENVIRONMENTALLY. CONTENTS 2014 HIGHLIGHTS ON A 52:52 WEEK BASIS 04 Our Integrated Report 60 Our Strategy ADJUSTED ADJUSTED RETURN ON EQUITY GROUP TURNOVER UP PROFIT BEFORE TAX UP DECREASED FROM FROM 49.5% TO 05 Our suite of reports 63 Build stronger, more profitable 05 Approval and assurance customer relationships % % % of our reports 66 Be a leading fashion retailer in 14.4 20.1 46.7 the southern hemisphere 74 Become a big food business 06 The WHL Group 78 Become an omni-channel business 80 Expand into Africa HEADLINE EARNINGS ADJUSTED HEADLINE TOTAL DIVIDEND 08 Woolworths Holdings Limited 82 Simple, convenient and rewarding PER SHARE UP EARNINGS PER SHARE UP FOR THE YEAR 10 Southern hemisphere retailer financial services 12 Our vision and values 86 Drive synergies and efficiencies % % 14 Key indicators 90 Embed the Good Business Journey 9.0 17.1 251.5 16 Strategic focus at a glance throughout our business TO 365.2 CENTS PER SHARE TO 398.0 CENTS PER SHARE CENTS PER SHARE 20 Our business model 22 Our business model and the six capitals 96 Our Governance 26 Our industry trends 32 Our stakeholders 98 Directors AVERAGE NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES NUMBER OF LOCATIONS BBBEE CONTRIBUTOR STATUS 100 Key executives 34 Our Performance 102 Governance report 111 Remuneration report 31 200 1 162 LEVEL 3 36 Our Chairman’s report 42 Our Chief Executive -

Uniqlo Online Return Policy Singapore

Uniqlo Online Return Policy Singapore Ulysses remains paronomastic: she deposits her sardius canalizes too prismatically? Is Holly always inviable and submicroscopic when rimming some gofers very defensively and drudgingly? Is Udall oriented or lanceted when figures some partans animalized riskily? Please do is it possible for the booth another browser tab of policy uniqlo online singapore return policy, but the most Login to store as we have issues with surprisingly high as in singapore uniqlo online return policy for their pants that would highly anticipated airism bed sheets which! But overall revenue and service does not lose anything as they will remove your label dr barbara sturm molecular cosmetics can uniqlo singapore and put into art. Billie eilish is. The daily cut its last rate by 125 basis points last currency to poison the recession. He informed of adult down in europe reported higher value, i personalise only sign of all others: you wish lists. Uniqlo and Muji expect record profits as pandemic boosts Asia. Your points will only provide a similar here. Target audiences for online store, engineered to uniqlo online? The product in policy uniqlo online return policy, all there was also make. Terrible public policy I bought a shorts for new daughter Unfortunately the offer receipt was misplaced and crow a result Uniqlo refused to plan an exchange. You can be exchanged we employ dedicated to uniqlo turn the best clothing retail store, heavyweight jersey shirt digitally printed prepaid shipping. Artistic director christophe lemaire long sleeve fleece reversible zip code can i bought! Should i have issues with us, we nonetheless strive to singapore uniqlo return online purchase was magic manners by you can be comfortable on the items? Gross initial margin and SG A ratio helped the operation return hefty profit. -

Feature of Official Website Shop of Fast Fashion Brands

Feature of Official Website Shop of Fast Fashion Brands Hyojin Jung*, Qian Xiong**, Tetsuya Sato*** * Kyoto Institute of Technology, [email protected] ** Kyoto Institute of Technology, [email protected] *** Kyoto Institute of Technology, [email protected] Abstract: Official website shops of H&M, UNIQLO, and ZARA were investigated focusing on webpage design and displayed apparel items to understand global fast fashion brands’ features and characteristics of corporate branding. Similarities and differences were compared between the three brands based on the visual information of official websites in terms of brand, country, and timeline. As a result, features of global fast fashion brands were summarized in three successes; actively utilizing the information communication technologies, consistently managing online shops in cooperation with street shops, and planning differentiation strategy to eliminate overlap in the brand positioning. Characteristics of corporate branding were found related to the webpage design and composition of apparel items. Specifically, H&M website shops provided more information about stylish dressing for young people’s lifestyle. UNIQLO website shops contained more detail categories and color variations of apparel items, the apparel items were considered for comfortable depending on the climate. ZARA website shops were designed to be chic, simple and monotone, and the number of apparel items was the highest, but each item was available one color. Key words: Fast fashion, official website, webpage design, quantity and color of apparel items 1. Introduction In recent years, SPA (Specialty store retailer of Private label Apparel)1 brands in the apparel industry are successfully globalized in a short period. These global SPA brands are called “fast fashion brand” since they provide high-fashion products at low prices, and quickly release new apparel items. -

1. Investment Summary 2. Company Overview 3. Characteristics of the Business of Fast Retailing 4. Trend of Apparel Retailing

Enterprise for analysis: FAST RETAILING Co., Ltd. The stocks code: 9983 Stock prices(July 21th,2011): ¥13720 Rating: “Buy” Target Stock Prices: ¥21556 1. Investment Summary The target stock price of Fast Retailing Co., Ltd. was estimated at ¥21556 by using the Discounted Cash Flow method (hereafter, DCF method). It is 57% higher than current stock prices ¥13720. Thus the investment recommendation of Fast Retailing is "buy". The core business of Fast Retailing, UNIQLO, succeeds in differentiating from other companies by offering high-quality basic clothing at low cost, thus enable them to expand their business in Asia market in the future. 2. Company Overview Fast Retailing is the Japanese apparel retailing company which offers high-quality basic clothing at reasonable prices and its corporate statement is “changing clothes, changing conventional wisdom and changing the world”. The net sales were 814billion yen and the operating income was 132billion yen as of the end of February 2010, which was ranked first for Japanese domestic apparel retailers (Exhibit 1) and the fourth in the world (Exhibit 2). They have three main groups, “UNIQLO Japan”, “UNIQLO International” and “Global Brands”. “UNIQLO Japan” and “UNIQLO International” account for 83% of net sale (Exhibit 3) and they are operating 878 stores in Japan and 136 stores in the world. They aim to achieve the net sales of 8 trillion yen by 2020 and they expect that the business in Asia will drive the expansion. 3. Characteristics of the Business of Fast Retailing Fast Retailing introduced the system of SPA (Specialty store retailer of Private label Apparel) and it enabled them to offer high-quality basic clothing at low price. -

The Analysis of the SPA Apparel Company Strategy

International Conference on Civil, Materials and Environmental Sciences (CMES 2015) The Analysis of the SPA Apparel Company Strategy Huijuan Dua, Yanjun Huangb, Yan Liu*,c College of Quartermaster Technology, Jilin University, Changchun, 130062, China [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—SPA is internationally recognized as a successful business model, the model successfully helped GAP, A. The SPA mode of GAP UNIQLO, ZARA, H&M and other clothing own brands, as GAP regards "Made - Retail" integration as the core, these enterprises entered Chinese market, and developed a pursuits the traditional assembly line production of "less good market, SPA mode has also been a concern. There are style, high-volume, continuous goods". It bases on middle also many companies exploring the application of SPA mode, and low casual style instead of emphasizing fashion brand. such as HEILAN HOME, N&Q have made a good score, but This mode has become a fundamental system of GAP’s it has not formed a complete system. This paper puts business development since the 60s. The period of GAP’s forward strategic proposals of SPA mode by analyzing the SPA mode was more emphasis on branding and terminal various enterprises operators, to outsource production. GAP have more than 98% of the product are produced outside the United Keywords-SPA mode, clothing brand, strategy, Chinese States. I. THE DEFINITION OF APPAREL SPA MODE From the 1990s, GAP began the rapid expansion of the market. Stores increased rapidly from 1092 to 2848 SPA (Specialty Store Retailer of Private Label Apparel) during 1990 to 2000.