Evaluation and Comparison of Electric Propulsion Motors for Submarines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N O T I C E This Document Has Been Reproduced From

N O T I C E THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED FROM MICROFICHE. ALTHOUGH IT IS RECOGNIZED THAT CERTAIN PORTIONS ARE ILLEGIBLE, IT IS BEING RELEASED IN THE INTEREST OF MAKING AVAILABLE AS MUCH INFORMATION AS POSSIBLE gg50- y-^ 3 (NASA-CH-163584) A STUDY OF TdE N80 -32856 APPLICABILITY/COMPATIbIL1TY OF INERTIAL ENERGY STURAGE SYSTEMS TU FU'IUAE SPACE MISSIONS Firnal C.eport (Texas Univ.) 139 p Unclas HC A07/MF AJ1 CSCL 10C G3/44 28665 CENTER FOR ELECTROMECHANICS OLD ^ l ^:' ^sA sit ^AC^utY OEM a^ 7//oo^6^^, THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING TAYLOR NAIL 167 AUSTIN, TEXAS, 71712 512/471-4496 4l3 Final Report for A Study of the Applicability/Compatibility of Inertial Energy Storage Systems to Future Space Missions Jet Propulsion Laboratory ... Contract No. 955619 This work was {performed for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology Sponsored by The National Aeronautics and Space Administration under Contract NAS7-100 by William F. Weldon r Technical Director Center for Electromechanics The University of Texas at Austin Taylor Hall 167 Austin, Texas 18712 (512) 471-4496 August, 1980 t c This document contains information prepared by the Center for Electromechanics of The University of Texas at Austin under JPL sub- contract. Its content is not necessarily endorsed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, or its sponsors. QpIrS r^r^..++r•^vT.+... .. ...^r..e.^^..^..-.^...^^.-Tw—.mss--rn ^s^w . ^A^^v^T'^'1^^w'aw^.^^'^.R!^'^rT-.. _ ..,^.wa^^.-.-.^.w r^.-,- www^w^^ -- r f Si i ABSTRACT The applicability/compatibility of inertial energy storage systems, i.e. -

Motors for Ship Propulsion

Motors for Ship Propulsion The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Kirtley, James L., Arijit Banerjee, and Steven Englebretson. “Motors for Ship Propulsion.” Proc. IEEE 103, no. 12 (December 2015): 2320– 2332. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2015.2487044 Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/102381 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ > REPLACE THIS LINE WITH YOUR PAPER IDENTIFICATION NUMBER (DOUBLE-CLICK HERE TO EDIT) < 1 Motors for Ship Propulsion James L. Kirtley Jr., Fellow, IEEE, Arijit Banerjee, Student Member, IEEE and Steven Englebretson, Member, IEEE machines but these are 'long shots' in the competition for use Abstract—Electric propulsion of ships has experienced steady in ship propulsion. expansion for several decades. Since the early 20th century, There is a substantial advantage in having a motor that icebreakers have employed the flexibility and easy control of DC can drive the propeller of a ship directly, not requiring a speed motors to provide for ship operations that split ice with back and reducing gearbox, and we will focus on such motors in this forth motion of the ship. More recently, cruise ships have paper. Shaft speeds range from about 100 to about 200 RPM employed diesel-electric propulsion systems to take advantage of for large ships, and power ratings per shaft range from about the flexibility of diesel, as opposed to steam engines, and because the electric plant can also be used for hotel loads. -

Inexpensive Inertial Energy Storage Utilizing Homopolar Motor- Generators

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine UMR-MEC Conference on Energy 09 Oct 1975 Inexpensive Inertial Energy Storage Utilizing Homopolar Motor- Generators W. F. Weldon H. H. Woodson H. G. Rylander M. D. Driga Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/umr-mec Part of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons, Mechanical Engineering Commons, Mining Engineering Commons, Nuclear Engineering Commons, and the Petroleum Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Weldon, W. F.; Woodson, H. H.; Rylander, H. G.; and Driga, M. D., "Inexpensive Inertial Energy Storage Utilizing Homopolar Motor-Generators" (1975). UMR-MEC Conference on Energy. 88. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/umr-mec/88 This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in UMR-MEC Conference on Energy by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INEXPENSIVE INERTIAL ENERGY STORAGE UTILIZING HOMOPOLAR MOTOR-GENERATORS W.F. Weldon, H.H. Woodson, H.G. Rylander, M.D. Driga Energy Storage Group 167 Taylor Hall The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78712 Abstract The pulsed power demands of the current generation of controlled thermonuclear fusion experiments have prompted a great interest in reliable, low cost, pulsed power systems. The Energy Storage Group at the University of Texas at Austin was created in response to this need and has worked for the past three years in developing inertial energy storage systems. -

Homopolar Superconducting AC Machines, with HTS Dynamo Driven Field Coils, for Aerospace Applications

Homopolar superconducting AC machines, with HTS dynamo driven field coils, for aerospace applications S Kalsi1, R A Badcock2, K Hamilton2 and J G Storey2 1Kalsi Green Power Systems, LLC, Princeton, NJ 08540 2 Robinson Research Institute, Victoria University of Wellington, Lower Hutt 5046, New Zealand [email protected] Abstract. There is worldwide interest in high-speed motors and generators with characteristics of compactness, light weight and high efficiency for aerospace applications. Several options are under consideration. However, machines employing high temperature superconductors (HTS) look promising for enabling machines with the desired characteristics. Machines employing excitation field windings on the rotor are constrained by the stress limit of rotor teeth and mechanisms for holding the winding at very high speed. Homopolar AC synchronous machines characteristically employ both the DC field excitation winding and AC armature windings in the stator. The rotor is merely a magnetic iron forging with salient pole lumps, which could be rotated at very high speeds up to the stress limit of the rotor materials. Rotational speeds of 50,000 RPM and higher are achievable. The high rotational speed enables more compact lightweight machines. This paper describes a 2 MW 25,000 RPM concept designs for machines employing HTS field excitation windings. The AC armature winding is made of actively cooled copper Litz conductor. The field winding consists of a small turn-count HTS coil that could be ramped up or down with a contactless HTS dynamo. This eliminates current leads spanning room-temperature and cryogenic regions and are major source for thermal conduction into the cryogenic region and thereby increase thermal load to be removed with refrigerators. -

130 Electrical Energy Innovations

130 Electrical Energy Innovations Gary Vesperman (Author) Advisor to Sky Train Corporation www.skytraincorp.com 588 Lake Huron Lane Boulder City, NV 89005-1018 702-435-7947 [email protected] www.padrak.com/vesperman TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 BRIEF SUMMARIES ....................................................................................................... 2 LARGE GENERATORS ............................................................................................... 13 Hydro-Magnetic Dynamo ............................................................................................ 13 Focus Fusion ............................................................................................................... 19 BlackLight Power’s Hydrino Generator ..................................................................... 19 IPMS Thorium Energy Accumulator .......................................................................... 22 Thorium Power Pack ................................................................................................... 22 Magneto-Gravitational Converter (Searl Effect Generator) ..................................... 23 Davis Tidal Turbine ..................................................................................................... 25 Magnatron – Light-Activated Cold Fusion Magnetic Motor ..................................... 26 Wireless Power and Free Energy from Ambient -

Modeling the Behavior of a Homopolar Motor

MODELING THE BEHAVIOR OF A HOMOPOLAR MOTOR A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science By GIANETTA MARIA BELARDE Dr. Thomas G. Engel, Thesis Supervisor December 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Thomas G. Engel. His motivation and insight provided me with the guidance to finish this project, and for that I will always be grateful to him. I would also like to thank several individuals who have provided me with guidance and support throughout my academic career, especially Prof. Michael Devaney, Prof. Robert O’Connell, Prof. Alex Iosevich, Dr. Jim Fischer, Dr. Gregory Triplett, and Dr. Guilherme DeSouza. Additionally, I would like to thank the other two members of my thesis committee, Dr. John Gahl and John Farmer. Finally, I wish to dedicate this work to my loving parents. Their lifelong support and caring has been instrumental in my life. ii MODELING THE BEHAVIOR OF A HOMOPOLAR MOTOR Gianetta Maria Belarde Dr. Thomas G. Engel, Thesis Supervisor ABSTRACT The design, construction, and operating characteristics of a homopolar motor are described in this thesis using both physical experimentation and simulation software. This type of motor converts electrical energy into mechanical energy using the Lorentz force. The torque from this force is used to propel the homopolar motor forward. The nickel-metal hydride batteries used in this study store 2500 mJ of energy. This energy is discharged by creating a short circuit between the anode and cathode of the battery using the armature, a piece of non-magnetic conductive wire. -

Homopolar Motor

California State University of Bakersfield, Department of Chemistry Homopolar Motor Standards: 3-PS2-3. Ask questions to determine cause and effect relationships of electric or magnetic interactions between two objects not in contact with each other. MS-PS2-3. Ask questions about data to determine the factors that affect the strength of electric and magnetic forces. Introduction: A homopolar motor is one of the simplest motors built due to the fact that it uses direct current to power the motor in one direction. The magnet’s magnetic field pushes up towards the battery and the current that flows from the battery travels perpendicularly from the magnetic field. This causes the creation of a force perpendicular to both the magnetic field and current. This force, known as the Lorentz force, is exerted on the copper wire (the conductor) causing it to spin (see Figure 2). Materials: AA Batteries Copper Wire Pliers Neodymium Magnet (ideal size: 12mm diameter x 6mm thick) This material is based upon work supported by the CSUB Revitalizing Science University Program (REVS-UP) funded by Chevron Corporation. Opinions or points of view expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Corporation or CSUB. Safety: Always have an adult with you to help you during your experiment. Always wear eye protection and gloves when doing chemistry experiments. Procedure: 1. Bend the copper wire into as many shapes as you would like, just make sure to follow the model shown in Figure 1 below. 2. Place the neodymium magnet on the negative side of the battery. -

Evaluation and Comparison of Electric Propulsion Motors for Submarines by Joel P

Evaluation and Comparison of Electric Propulsion Motors for Submarines by Joel P. Harbour B.S., Electrical Engineering University of Wyoming, 1991 Submitted to the Departments of Ocean Engineering and Electrical Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of NAVAL ENGINEER and MASTER of SCIENCE in ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING and COMPUTER SCIENCE at the MASSACHISETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 2001 c) 2001 Joel P. Harbour. All rights --eserved The author hereby grants to Massachusetts Institute of Technology permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of thg1jesis documen.4n whole or in part. Signature of A uthor ............ ........... ... .......................................... Denart ennts of 'cean Engineering and Electrical Engineering 11 May 2001 Certified by ................ ................... James L. Kirtley Jr. Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering T----Tbesis Supervisor Certified by................ .................. Clifford A. Whitcomb Assoc ate Professor of Ocean Engineering Thesiq, pervisor Accepted by ..... ........................ Arthur U. smith Chairman, Committee on ate Students DePartment of Electrical EngineeringwA-1 16r uter Science Accepted by ................... Henr-ik- Sch-midt MASSACHUSETTS INSTIT TEhaifm-iao6 ieote on Graduate Students OF TECHNOLOGY Depa- ent'6f Ocean Engineering JUL 11 ?i BARKER LIBRARIES Evaluation and Comparison of Electric Propulsion Motors for Submarines by Joel P. Harbour Submitted to the Departments of Ocean Engineering and Electrical Engineering on 11 May 2001, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of NAVAL ENGINEER and MASTER of SCIENCE in ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING and COMPUTER SCIENCE Abstract The Navy has announced its conviction to make its warships run on electric power through the decision to make its newest line of destroyers propelled with an electric propulsion system [1]. -

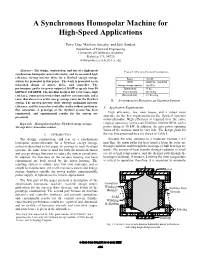

A Synchronous Homopolar Machine for High-Speed Applications

A Synchronous Homopolar Machine for High-Speed Applications Perry Tsao, Matthew Senesky, and Seth Sanders Department of Electrical Engineering University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 www-power.eecs.berkeley.edu Abstract— The design, construction, and test of a high-speed TABLE I. MACHINE DESIGN PARAMETERS synchronous homopolar motor/alternator, and its associated high efficiency six-step inverter drive for a flywheel energy storage Power 30 kW system are presented in this paper. The work is presented as an RPM 50kRPM- 100kRPM integrated design of motor, drive, and controller. The Energy storage capacity 140 W.hr performance goal is for power output of 30 kW at speeds from 50 System mass 36 kg kRPM to 100 kRPM. The machine features low rotor losses, high Power density 833 W/kg efficiency, construction from robust and low cost materials, and a Energy density 3.9 W.hr/kg rotor that also serves as the energy storage rotor for the flywheel II. SYNCHRONOUS HOMOPOLAR MACHINE DESIGN system. The six-step inverter drive strategy maximizes inverter efficiency, and the sensorless controller works without position or A. Application Requirements flux estimation. A prototype of the flywheel system has been constructed, and experimental results for the system are High efficiency, low rotor losses, and a robust rotor presented. structure are the key requirements for the flywheel system’s motor/alternator. High efficiency is required over the entire Keywords—Homopolar machine; Flywheel energy storage; range of operation, in this case 50,000 to 100,000 RPM, with a Six-step drive; Sensorless control power rating of 30 kW. -

Tiny Dancers (A Homopolar Motor) Because Harnessing Refers to Making Use of Resources to Produce Energy We Decided to Try Maki

Tiny Dancers (A Homopolar Motor) Because harnessing refers to making use of resources to produce energy we decided to try making a homopolar motor. A homopolar motor is probably the simplest DIY motor you can make. You need just a few easy to obtain items and it’s FAIRLY simple to construct. Homopolar motors are not useful motors in anything but science experiments but they do demonstrate some interesting concepts and are fun to watch! They are also a great introduction to electricity and electromagnetism. Materials: • Copper Wire- THIS is the gauge we used • 1/2″ x 1/8″ Neodymium Disc Magnets • AA Battery • 3 in 1 Combination Tool or pliers/wire cutters • Template • Crepe Paper (optional for skirt) • Hot Glue (optional) Instructions 1. Cut a long piece of wire off your spool, I started with about a 10” long piece. Lay it on the template of your choice and bend as shown using 3-in 1 tool or pliers. No need to be perfect HOWEVER try and keep your form as symmetrical as possible. 2. To create the base section of wire that wraps the magnets, I recommend bending the end of the wire around the battery. Remove the battery and gently widen the circular wire form with your fingers. 3. Place three neodymium magnets on the negative side of your battery. 4. Place the motor on top of the battery so that it touches the positive pole. The round section at the bottom of th motor must be low enough to encircle the magnets! 5. Let it go. -

AC Motor INTRODUCTION

AC motor INTRODUCTION An AC motor is an electric motor that is driven by an alternating current. It consists of two basic parts, an outside stationary stator having coils supplied with alternating current to produce a rotating magnetic field, and an inside rotor attached to the output shaft that is given a torque by the rotating field. There are two types of AC motors, depending on the type of rotor used. The first is the synchronous motor, which rotates exactly at the supply frequency or a submultiple of the supply frequency. The magnetic field on the rotor is either generated by current delivered through slip rings or by a permanent magnet. The second type is the induction motor, which turns slightly slower than the supply frequency. The magnetic field on the rotor of this motor is created by an induced current. History In 1882, Serbian inventor Nikola Tesla identified the rotating magnetic induction field principle[citation needed] and pioneered the use of this rotating and inducting electromagnetic field force to generate torque in rotating machines. He exploited this principle in the design of a poly-phase induction motor in 1883. In 1885, Galileo Ferraris independently researched the concept. In 1888, Ferraris published his research in a paper to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Turin. Introduction of Tesla's motor from 1888 onwards initiated what is sometimes referred to as the Second Industrial Revolution, making possible both the efficient generation and long distance distribution of electrical energy using the alternating current transmission system, also of Tesla's invention (1888).[1] Before widespread use of Tesla's principle of poly-phase induction for rotating machines, all motors operated by continually passing a conductor through a stationary magnetic field (as in homopolar motor). -

Control Or Regulation of Electric Motors, Electric Generators Or Dynamo-Electric Converters; Controlling Transformers, Reactors Or Choke Coils

CPC - H02P - 2017.08 H02P CONTROL OR REGULATION OF ELECTRIC MOTORS, ELECTRIC GENERATORS OR DYNAMO-ELECTRIC CONVERTERS; CONTROLLING TRANSFORMERS, REACTORS OR CHOKE COILS Definition statement This place covers: Arrangements for • starting, • regulating, • electronically commutating, • braking, or otherwise controlling: • motors, • generators, • dynamo-electric converters, clutches, brakes, gears, • transformers, • reactors or choke coils, of the types classified in the relevant subclasses, e.g. H01F, H02K. References Limiting references This place does not cover: Arrangements for merely turning on an electric motor to drive a machine A47L 9/28, F02N 11/00 or device, e.g.: vacuum cleaner, vehicle starter motor Hybrid vehicle, conjoint control, arrangements for mounting B60K, B60W Arrangements for controlling electric generators for charging batteries H02J 7/00 Arrangements for starting, regulating, electronically commutating, H02N braking, or otherwise controlling electric machines not otherwise provided for, e.g. machines using piezo-electric effects Informative references Attention is drawn to the following places, which may be of interest for search: Curtain A47H Hand hammers, drills B25D 17/00 Printers B41J Power steering B42D 5/00 Heating cooling ventilating B60H 1/00 Electrically propelled vehicles, current collector, maglev B60L Lighting B60Q 1/00 Electric circuits for vehicle B60R, H02J Wiper control B60S 1/00 Marine B63H 1 H02P (continued) CPC - H02P - 2017.08 Elevator B66B Washing machines, household appliances D06F 39/00 Sliding