Cut from a Different Cloth: Examining the Role Hip-Hop Plays In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hip Hop America Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HIP HOP AMERICA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nelson George | 256 pages | 31 May 2005 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780143035152 | English | New York, NY, United States Hip HOP America PDF Book Kool Herc -- lay the foundation of the hip-hop movement. Stylistically, southern rap relies on exuberant production and direct lyrics typically about the southern lifestyle, trends, attitudes. Hill's brilliant songwriting flourished from song to song, whether she was grappling with spirituality "Final Hour," "Forgive Them, Father" or stroking sexuality without exploiting it "Nothing Even Matters". According to a TIME magazine article, Wrangler was set to launch a collection called "Wrapid Transit," and Van Doren Rubber was putting out a special version of its Vans wrestling shoe designed especially for breaking [source: Koepp ]. Another key element that's helping spread the hip-hop word is the Internet. Late Edition East Coast. Most hip-hop historians speak of four elements of hip-hop: tagging graffiti , b-boying break dancing , emceeing MCing and rapping. Taking Hip-Hop Seriously. Related Content " ". Regardless, the Bay Area has enjoyed a measurable amount of success with their brainchild. And then, in the mid to late s, there was a resurgence in the popularity of breaking in the United States, and it has stayed within sight ever since. Depending on how old you are, when someone says "hip-hop dance," you could picture the boogaloo, locking, popping, freestyle, uprocking, floor- or downrocking, grinding, the running man, gangsta walking, krumping, the Harlem shake or chicken noodle soup. Another thing to clear up is this: If you think hip-hop and rap are synonymous, you're a little off the mark. -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

DJ Skills the Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3

The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 1 74 The Rise of The Hip-hop DJ DJs were Hip-hop’s original architects, and remain crucial to its contin- ued development. Hip-hop is more than a style of music; it’s a culture. As with any culture, there are various artistic expressions of Hip-hop, the four principal expressions being: • visual art (graffiti) • dance (breaking, rocking, locking, and popping, collectively known in the media as “break dancing”) • literature (rap lyrics and slam poetry) • music (DJing and turntablism) Unlike the European Renaissance or the Ming Dynasty, Hip-hop is a culture that is very much alive and still evolving. Some argue that Hip-hop is the most influential cultural movement in history, point- ing to the globalization of Hip-hop music, fashion, and other forms of expression. Style has always been at the forefront of Hip-hop. Improvisation is called free styling, whether in rap, turntablism, breaking, or graf- fiti writing. Since everyone is using the essentially same tools (spray paint for graffiti writers, microphones for rappers and beat boxers, their bodies for dancers, and two turntables with a mixer for DJs), it’s the artists’ personal styles that set them apart. It’s no coincidence that two of the most authentic movies about the genesis of the move- ment are titled Wild Style and Style Wars. There are also many styles of writing the word “Hip-hop.” The mainstream media most often oscillates between “hip-hop” and “hip hop.” The Hiphop Archive at Harvard writes “Hiphop” as one word, 2 DJ Skills The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3 with a capital H, embracing KRS-ONE’s line of reasoning that “Hiphop Kool DJ Herc is a culture with its own foundation narrative, history, natives, and 7 In 1955 in Jamaica, a young woman from the parish of Saint Mary mission.” After a great deal of input from many people in the Hip-hop community, I’ve decided to capitalize the word but keep the hyphen, gave birth to a son who would become the father of Hip-hop. -

View Centro's Film List

About the Centro Film Collection The Centro Library and Archives houses one of the most extensive collections of films documenting the Puerto Rican experience. The collection includes documentaries, public service news programs; Hollywood produced feature films, as well as cinema films produced by the film industry in Puerto Rico. Presently we house over 500 titles, both in DVD and VHS format. Films from the collection may be borrowed, and are available for teaching, study, as well as for entertainment purposes with due consideration for copyright and intellectual property laws. Film Lending Policy Our policy requires that films be picked-up at our facility, we do not mail out. Films maybe borrowed by college professors, as well as public school teachers for classroom presentations during the school year. We also lend to student clubs and community-based organizations. For individuals conducting personal research, or for students who need to view films for class assignments, we ask that they call and make an appointment for viewing the film(s) at our facilities. Overview of collections: 366 documentary/special programs 67 feature films 11 Banco Popular programs on Puerto Rican Music 2 films (rough-cut copies) Roz Payne Archives 95 copies of WNBC Visiones programs 20 titles of WNET Realidades programs Total # of titles=559 (As of 9/2019) 1 Procedures for Borrowing Films 1. Reserve films one week in advance. 2. A maximum of 2 FILMS may be borrowed at a time. 3. Pick-up film(s) at the Centro Library and Archives with proper ID, and sign contract which specifies obligations and responsibilities while the film(s) is in your possession. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

Music 04: Global Sound—Jeffers Engelhardt 1

Music 04: Global Sound—Jeffers Engelhardt 1 ❦ MUSIC 04: GLOBAL SOUND ❦ COURSE INFORMATION Arms Music Center 212 Monday, Wednesday 2:00-3:20 Assistant Professor Jeffers Engelhardt Arms Music Center 5 413.542.8469 (office) 413.687.0855 (home) [email protected] http://www.amherst.edu/~jengelhardt Office hours: anytime by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION AND REQUIREMENTS This course explores the global scale of much music-making and musical consumption today. Migration, diaspora, war, tourism, postsocialist and postcolonial change, commerce, and digital technology have all profoundly reshaped the way musics are created, circulated, and consumed. These forces have also illuminated important ethical, legal, and aesthetic issues concerning intellectual property rights and the nature of musical authorship, the appropriation of “traditional” musics by elites in the global North, and local musical responses to transnational music industries, for instance. Through a series of case studies that will include performances and workshops by visiting musicians, Global Sound will examine how musics animate processes of globalization and how globalization affects musics by establishing new social, cultural, and economic formations. Your work in this course will be challenging, rewarding, and varied. You will be asked to present your work in class and make weekly postings to the course blog. There are also a few events outside of class time that you will need to participate in. I will hand out guidelines and rubrics for all the work you will do in order to make my expectations and standards for evaluation completely clear. Needless to say, preparation for, attendance at, and active participation in every class meeting is essential. -

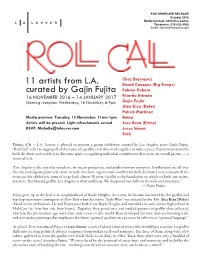

11 Artists from L.A. Curated by Gajin Fujita

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 2016 Media Contact: Christina Carlos Telephone: 310-822-4955 Email: [email protected] Chaz Bojorquez 11 artists from L.A. David Cavazos (Big Sleeps) curated by Gajin Fujita Fabian Debora 16 NOVEMBER 2016 – 14 JANUARY 2017 Ricardo Estrada Opening reception: Wednesday, 16 November, 6-9pm Gajin Fujita Alex Kizu (Defer) Patrick Martinez Media preview: Tuesday, 15 November, 11am-1pm Retna Artists will be present. Light refreshments served Jose Reza (Prime) RSVP: [email protected] Jesse Simon Slick Venice, CA -- L.A. Louver is pleased to present a group exhibition curated by Los Angeles artist Gajin Fujita. “Roll Call” refers to tagging all of the names of a graffiti crew who work together to make a piece. Fujita’s inspiration for both the show and its title is in this same spirit, recognizing individual contributors that create an overall picture — a vision of L.A. “Los Angeles is the city that raised me, its streets guided me, and graffiti was my transport. Graffiti took me all over the city, seeking out prime real estate to stake my claim, tag my name and flex my skills. It’s how I came to know all the artists in this exhibition; some of us go back almost 30 years. Graffiti is the foundation on which we built our artistic practices. But beyond graffiti, Los Angeles is what unifies us. We sharpened our skills on its walls and structures.” — Gajin Fujita Fujita grew up in the East L.A. neighborhood of Boyle Heights. As a teen, he became fascinated by the graffiti and hip-hop movement coming out of New York when the movie “Style Wars” was released in the ’80s. -

Marissa K. Munderloh Phd Thesis

The Emergence of Post-Hybrid Identities: a Comparative Analysis of National Identity Formations in Germany’s Contemporary Hip-Hop Culture Marissa Kristina Munderloh This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 3 October 2014 Abstract This thesis examines how hip-hop has become a meaningful cultural movement for contemporary artists in Hamburg and in Oldenburg. The comparative analysis is guided by a three-dimensional theoretical framework that considers the spatial, historical and social influences, which have shaped hip-hop music, dance, rap and graffiti art in the USA and subsequently in the two northern German cities. The research methods entail participant observation, semi-structured interviews and a close reading of hip-hop’s cultural texts in the form of videos, photographs and lyrics. The first chapter analyses the manifestation of hip-hop music in Hamburg. The second chapter looks at the local adaptation of hip-hop’s dance styles. The last two chapters on rap and graffiti art present a comparative analysis between the art forms’ appropriation in Hamburg and in Oldenburg. In comparing hip-hop’s four main elements and their practices in two distinct cities, this research project expands current German hip-hop scholarship beyond the common focus on rap, especially in terms of rap being a voice of the minority. It also offers insights into the ways in which artists express their local, regional or national identity as a culturally hybrid state, since hip-hop’s art forms have always been the result of cultural and artistic mixture. -

The Intertextuality and Translations of Fine Art and Class in Hip-Hop Culture

arts Article The Intertextuality and Translations of Fine Art and Class in Hip-Hop Culture Adam de Paor-Evans Faculty of Culture and the Creative Industries, University of Central Lancashire, Lancashire PR1 2HE, UK; [email protected] Received: 24 October 2018; Accepted: 12 November 2018; Published: 16 November 2018 Abstract: Hip-hop culture is structured around key representational elements, each of which is underpinned by the holistic element of knowledge. Hip-hop emerged as a cultural counter position to the socio-politics of the urban condition in 1970s New York City, fuelled by destitution, contextual displacement, and the cultural values of non-white diaspora. Graffiti—as the primary form of hip-hop expression—began as a political act before morphing into an artform which visually supported the music and dance elements of hip-hop. The emerging synergies graffiti shared with the practices of DJing, rap, and B-boying (breakdancing) forged a new form of art which challenged the cultural capital of music and visual and sonic arts. This article explores moments of intertextuality between visual and sonic metaphors in hip-hop culture and the canon of fine art. The tropes of Michelangelo, Warhol, Monet, and O’Keefe are interrogated through the lyrics of Melle Mel, LL Cool J, Rakim, Felt, Action Bronson, Homeboy Sandman and Aesop Rock to reveal hip-hop’s multifarious intertextuality. In conclusion, the article contests the fallacy of hip-hop as mainstream and lowbrow culture and affirms that the use of fine art tropes in hip-hop narratives builds a critical relationship between the previously disparate cultural values of hip-hop and fine art, and challenges conventions of the class system. -

3345/ the Roots of Latina/O Hip Hop / Spring 2020/ Carrizal-Dukes

Spring 2020 - Jan 21, 2020 - Mar 08, 2020 The Roots of Latina/o Hip Hop CHIC 3345 – 001 CRN 26401 Syllabus 3 credits 100% Online The University of Texas at El Paso Chicano Studies Program 500 W. University Ave. Graham Hall #104 El Paso, Texas 79968 CS Phone: 915-747-5462 Fax: 915-747-6501 Course Instructor: Elvira Carrizal-Dukes, MFA Virtual Office Hours: MW 5:00 pm – 6:00 pm Google Hangouts or by appointment (Please contact me through Blackboard course messages to schedule appointment.) Office Phone: 915-747-5985 Mailbox: Chicano Studies Office, GRAH 104 E-mail: [email protected] Content Introduction The Roots of Latina/o Hip Hop is designed to engage students in the aural, visual, social, and political history of Latina/o Hip Hop and its intersection with African American music and art. This course provides students with an overview of Latina/o Hip Hop history. Students will learn to analyze and critique music, lyrics, aesthetics, genres, musician biographies and events studied in the course. Course Objective The Roots of Latina/o Hip Hop is designed to assist you in learning the history, aesthetics, and motifs of Latina/o Hip Hop through lectures, readings, screenings/listenings, discussions and assignments. This class provides opportunities for you to develop your personal vision and expression. Course Description The Roots of Latina/o Hip Hop: The Sounds of Struggle This course examines the musical, social, political, cultural, and economic conditions that brought about urban youth culture in the late 1970s in the Bronx. Special focus will be placed on the multicultural aspect of the birth of hip-hop, wherein youth forge an alternative culture based on the collected awareness of the plight of the urban non-White working class in America. -

Visit Us Online At

This study guide was designed to help teachers prepare their classes to see a performance of BREAK! The Urban Funk Spectacular The guide describes the history of the company and includes a series of discussion questions, some activities you may want to do with your class as well as a few terms to remember. We hope it will be useful, and that you and your class find this performance both entertaining and educational. Visit us online at www.breakshow.com WHAT IS URBAN DANCE? URBAN DANCE or STREET DANCING, as we know it today involves Locking, Popping, Breaking, street style jazz and other forms of dance that developed out of urban culture rooted in American cities. It is deeply connected to Hip-Hop music and has become accepted as a legitimate art form seen across the world on television, videos and on theatrical stages as well as utilized in choreography by major dance companies. Locking Locking style involves a “clown look” fun movements like “the funky chicken” and other comedy moves. This was a dance style that was originally a “goof” dance or a “mistake” that became a media sensation with early 1970 TV shows based on unique characters and style. Some teachers out there might remember charactors like Re-Run! The significance of “Locking” was that it was the first style of Urban Dance gathering media attention. Robotics and Electric Boogaloo This style of dance became popular with the electronic funk sound and drum beat in songs in 70’s and 80’s. Many of you might have seen videos of “Michael Jackson’s Dancing Machine” and other Robotic dances of that era! WHAT IS BREAK DANCE? Although the exact beginning of Break dance is unclear, it seems to have emerged as a style of street dance during the 1970's. -

Henry Chalfant: Art Vs

Henry Chalfant: Art vs. Transit, 1977-1987 The definitive exhibition of photographs documenting subway paintings to receive a long awaited homecoming at the Bronx Museum. Henry Chalfant. Dust Sin, 1980. Courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery. On View: September 25, 2019—March 8, 2020 (Bronx, NY — June 19, 2019) — The Bronx Museum of the Arts is pleased to announce Henry Chalfant: Art vs. Transit, 1977-1987, the first U.S. retrospective of the pioneering photographer, on view from September 25, 2019 to March 8, 2020. Recognized as one of the most significant documentarians of subway art, Chalfant’s photographs and films immortalized this ephemeral art form from its Bronx-born beginnings, helping to launch graffiti art into the international phenomenon it is today. The historic exhibition looks back at a rebellious art form launched in the midst of a tumultuous time in New York City history. Chalfant’s graffiti archives are a work of visual anthropology and one of the seminal documents of American popular culture in the late twentieth century. Left: Henry Chalfant. Mattress Acrobats Ready to Go, South Bronx, NY, 1985. Right: Henry Chalfant. Shoot the Pump, South Bronx, NY, 1985. Courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery. Starting in the early 1970s, graffiti became a cultural movement, along with hip-hop and breakdancing, created by teenagers and young people who used the infrastructure of the city, its streets and subway cars, to circulate their tags, murals, and radical visual expressions. Through the lens of Henry Chalfant, the public will be able to see the now largely disappeared works of legendary subway writers, including Dondi, Futura, Lady Pink, Lee Quiñones, and Zephyr, and Bronx legends including Blade, Crash, DAZE, Dez, Kel, Mare, SEEN, Skeme, and T-Kid.