Models for Protecting the Environment for Future Generations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media

Henry Jenkins Convergence Culture Where Old and New Media Collide n New York University Press • NewYork and London Skenovano pro studijni ucely NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress. org © 2006 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jenkins, Henry, 1958- Convergence culture : where old and new media collide / Henry Jenkins, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-4281-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media and culture—United States. 2. Popular culture—United States. I. Title. P94.65.U6J46 2006 302.230973—dc22 2006007358 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America c 15 14 13 12 11 p 10 987654321 Skenovano pro studijni ucely Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: "Worship at the Altar of Convergence": A New Paradigm for Understanding Media Change 1 1 Spoiling Survivor: The Anatomy of a Knowledge Community 25 2 Buying into American Idol: How We are Being Sold on Reality TV 59 3 Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling 93 4 Quentin Tarantino's Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry 131 5 Why Heather Can Write: Media Literacy and the Harry Potter Wars 169 6 Photoshop for Democracy: The New Relationship between Politics and Popular Culture 206 Conclusion: Democratizing Television? The Politics of Participation 240 Notes 261 Glossary 279 Index 295 About the Author 308 V Skenovano pro studijni ucely Acknowledgments Writing this book has been an epic journey, helped along by many hands. -

The History of Web Comics Pdf Free Download

THE HISTORY OF WEB COMICS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK T. Campbell | 192 pages | 06 Jun 2006 | Antarctic Press Inc | 9780976804390 | English | San Antonio, Texas, United States The History of Web Comics PDF Book When Alexa goes to put out the fire, her clothes get burnt away, and she threatens Sam and Fuzzy with the fire extinguisher. Columbus: Ohio State U P. Stanton , Eneg and Willie in his book 'The Adventures of Sweet Gwendoline' have brought this genre to artistic heights. I would drive back and forth between Massachusetts and Connecticut in my little Acura, with roof racks so I could put boxes of shirts on top of the car. I'll split these up where I think best using a variety of industry information. Kaestle et. The Creators Issue. To learn more or opt-out, read our Cookie Policy. Authors are more accessible to their readers than before, and often provide access to works in progress or to process videos based on requests about how they create their comics. Thanks to everyone who's followed our work over the years and lent a hand in one way or another. It was very meta. First appeared in July as shown. As digital technology continues to evolve, it is difficult to predict in what direction webcomics will develop. The History of EC Comics. Based on this analysis, I argue that webcomics present a valuable archive of digital media from the early s that shows how relationships in the attention economy of the digital realm differ from those in the economy of material goods. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Dc Comics: Wonder Woman: Wisdom Through the Ages Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DC COMICS: WONDER WOMAN: WISDOM THROUGH THE AGES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Avila | 192 pages | 29 Sep 2020 | Insight Editions | 9781683834779 | English | San Rafael, United States DC Comics: Wonder Woman: Wisdom Through the Ages PDF Book Instead, she receives the ability to transform into the catlike Cheetah, gaining superhuman strength and speed; the ritual partially backfires, and her human form becomes frail and weak. Diana of Themyscira Arrowverse Batwoman. Since her creation, Diana of Themyscira has made a name for herself as one of the most powerful superheroes in comic book existence. A must-have for Wonder Woman fans everywhere! Through close collaboration with Jason Fabok, we have created the ultimate Wonder Woman statue in her dynamic pose. The two share a degree of mutual respect, occasionally fighting together against a common enemy, though ultimately Barbara still harbors jealousy. Delivery: 23rdth Jan. Published 26 November Maria Mendoza Earth Just Imagine. Wonder Girl Earth She returned to her classic look with help from feminist icon Gloria Steinem, who put Wonder Woman — dressed in her iconic red, white, and blue ensemble — on the cover of the first full-length issue of Ms. Priscilla eventually retires from her Cheetah lifestyle and dies of an unspecified illness, with her niece Deborah briefly taking over the alter ego. In fact, it was great to see some of the powers realized in live-action when the Princess of Themyscira made her big screen debut in the Patty Jenkins directed, Wonder Woman. Submit Review. Although she was raised entirely by women on the island of Themyscira , she was sent as an ambassador to the Man's World, spreading their idealistic message of strength and love. -

Our Common Future

Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future Table of Contents Acronyms and Note on Terminology Chairman's Foreword From One Earth to One World Part I. Common Concerns 1. A Threatened Future I. Symptoms and Causes II. New Approaches to Environment and Development 2. Towards Sustainable Development I. The Concept of Sustainable Development II. Equity and the Common Interest III. Strategic Imperatives IV. Conclusion 3. The Role of the International Economy I. The International Economy, the Environment, and Development II. Decline in the 1980s III. Enabling Sustainable Development IV. A Sustainable World Economy Part II. Common Challenges 4. Population and Human Resources I. The Links with Environment and Development II. The Population Perspective III. A Policy Framework 5. Food Security: Sustaining the Potential I. Achievements II. Signs of Crisis III. The Challenge IV. Strategies for Sustainable Food Security V. Food for the Future 6. Species and Ecosystems: Resources for Development I. The Problem: Character and Extent II. Extinction Patterns and Trends III. Some Causes of Extinction IV. Economic Values at Stake V. New Approach: Anticipate and Prevent VI. International Action for National Species VII. Scope for National Action VIII. The Need for Action 7. Energy: Choices for Environment and Development I. Energy, Economy, and Environment II. Fossil Fuels: The Continuing Dilemma III. Nuclear Energy: Unsolved Problems IV. Wood Fuels: The Vanishing Resource V. Renewable Energy: The Untapped Potential VI. Energy Efficiency: Maintaining the Momentum VII. Energy Conservation Measures VIII. Conclusion 8. Industry: Producing More With Less I. Industrial Growth and its Impact II. Sustainable Industrial Development in a Global Context III. -

Batman Honored by U.S. Postal Service to Celebrate 75 Years of the Timeless Super Hero

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Mark Saunders Sept 29, 2014 202-268-6524 [email protected] usps.com/news Batman Honored by U.S. Postal Service to Celebrate 75 Years of the Timeless Super Hero Eight Limited Edition Forever Stamps Celebrate Batman’s Evolution in Comics High-resolution images of the stamps are available for media use only by emailing: [email protected] WASHINGTON, D.C. and BURBANK, CA — The U.S. Postal Service, in collaboration with Warner Bros. Consumer Products and DC Entertainment, is proud to announce that Batman, one of DC Comics’ most beloved characters, will be immortalized in a Limited Edition Forever postage stamp collection. The first-day-of-issue dedication ceremony for the Limited Edition Forever Batman Stamp Collection Set will take place in “Gotham City,” at 10:30 a.m., Oct. 9 at the Javits Center to kick off New York Comic Con 2014. In honor of Batman’s 75th anniversary as the protector of Gotham City, he will join the elite ranks of American pop-culture icons that have been given this honor. The stamp collection will feature multiple images of the Caped Crusader from artistically distinct periods across his comic book history, exhibiting the evolution of the Dark Knight over the past seven-and-a-half decades. “The U.S. Postal Service has a long history of celebrating America’s icons, from political figures to pop-culture’s most colorful characters. We are thrilled to bring Batman off the pages of DC Comics and onto the limited edition Forever Batman stamp collection, marking his place in American history,” said U.S. -

Watchmen Thesis

1 I. Introduction My argument begins with a quote from the blog of Tony Long, a writer for the magazine Wired , a magazine which is immersed in popular culture and technology, and is usually ahead of the times in its cultural evaluations. However, there are still some areas in which the writers are not completely aware of the changes of genre, as Long demonstrates in his argument for why a graphic novel that was recently nominated for the National Book Award should not be eligible. Long says, I have not read this particular "novel" but I'm familiar with the genre so I'm going to go out on a limb here. First, I'll bet for what it is, it's pretty good. Probably damned good. But it's a comic book. And comic books should not be nominated for National Book Awards, in any category. That should be reserved for books that are, well, all words. This is not about denigrating the comic book, or graphic novel, or whatever you want to call it. This is not to say that illustrated stories don't constitute an art form or that you can't get tremendous satisfaction from them. This is simply to say that, as literature, the comic book does not deserve equal status with real novels, or short stories. (para 15-16) Long feels quite strongly that graphic novels are “comic books,” and does not know of any distinction between the two. He considers “comic books” and graphic novels to both be “illustrated stories” and so not eligible to be considered “literature.” His distinction of literature seems to be that of novels and short stories, and the reason those are literary is because they are “all words.” Long is displaying a prejudice towards what he considers “comic books” that is endemic to the mind of the American reader, and most American scholars. -

With Great Power: Examining the Representation and Empowerment of Women in DC and Marvel Comics Kylee Kilbourne

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 12-2017 With Great Power: Examining the Representation and Empowerment of Women in DC and Marvel Comics Kylee Kilbourne Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kilbourne, Kylee, "With Great Power: Examining the Representation and Empowerment of Women in DC and Marvel Comics" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 433. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/433 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WITH GREAT POWER: EXAMINING THE REPRESENTATION AND EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN IN DC AND MARVEL COMICS by Kylee Kilbourne East Tennessee State University December 2017 An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment For the Midway Honors Scholars Program Department of Literature and Language College of Arts and Sciences ____________________________ Dr. Phyllis Thompson, Advisor ____________________________ Dr. Katherine Weiss, Reader ____________________________ Dr. Michael Cody, Reader 1 ABSTRACT Throughout history, comic books and the media they inspire have reflected modern society as it changes and grows. But women’s roles in comics have often been diminished as they become victims, damsels in distress, and sidekicks. This thesis explores the problems that female characters often face in comic books, but it also shows the positive representation that new creators have introduced over the years. -

Mythic Symbols of Batman

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2007-11-28 Mythic Symbols of Batman John J. Darowski Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Classics Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Darowski, John J., "Mythic Symbols of Batman" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 1226. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1226 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Mythic Symbols of Batman by John Jefferson Darowski A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Studies Brigham Young University December 2007 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by John J. Darowski This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. _____________________________ ____________________________________ Date Kerry Soper, Chair _____________________________ ____________________________________ Date Carl Sederholm _____________________________ ____________________________________ Date Charlotte Stanford Brigham Young University As chair of the candidate‟s graduate committee, I have read the thesis by John J. Darowski in its final form and have found that (1) its form, citations and bibliographical style are consistent and acceptable to fulfill university and department style requirements; (2) its illustrative materials, including figures, tables and charts are in place; and (3) the final manuscript is satisfactory to the graduate committee and is ready for submission to the university library. -

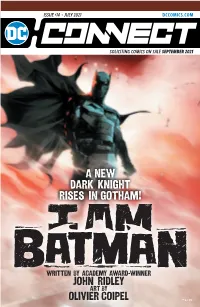

A New Dark Knight Rises in Gotham!

ISSUE #14 • JULY 2021 DCCOMICS.COM SOLICITING COMICS ON SALE SEPTEMBER 2021 A New Dark Knight rises in Gotham! Written by Academy Award-winner JOHN RIDLEY A r t by Olivier Coipel ™ & © DC #14 JULY 2021 / SOLICITING COMICS ON SALE IN SEPTEMBER WHAT’S INSIDE BATMAN: FEAR STATE 1 The epic Fear State event that runs across the Batman titles continues this month. Don’t miss the first issue of I Am Batman written by Academy Award-winner John Ridley with art by Olivier Coipel or the promotionally priced comics for Batman Day 2021 including the Batman/Fortnite: Zero Point #1 special edition timed to promote the release of the graphic novel collection. BATMAN VS. BIGBY! A WOLF IN GOTHAM #1 12 The Dark Knight faces off with Bigby Wolf in Batman vs. Bigby! A Wolf in Gotham #1. Worlds will collide in this 6-issue crossover with the world of Fables, written by Bill Willingham with art by Brian Level. Fans of the acclaimed long-running Vertigo series will not want to miss the return of one of the most popular characters from Fabletown. THE SUICIDE SQUAD 21 Interest in the Suicide Squad will be at an all-time high after the release of The Suicide Squad movie written and directed by James Gunn. Be sure to stock up on Suicide Squad: King Shark, which features the breakout character from the film, and Harley Quinn: The Animated Series—The Eat. Bang. Kill Tour, which spins out of the animated series now on HBO Max. COLLECTED EDITIONS 26 The Joker by James Tynion IV and Guillem March, The Other History of the DC Universe by John Ridley and Giuseppe Camuncoli, and Far Sector by N.K. -

The Evolution of Superman As a Reflection of American Society

Bellarmine University ScholarWorks@Bellarmine Undergraduate Theses Undergraduate Works 4-26-2020 Dissecting the Man of Steel: The Evolution of Superman as a Reflection of American Society Marie Gould [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Gould, Marie, "Dissecting the Man of Steel: The Evolution of Superman as a Reflection of American Society" (2020). Undergraduate Theses. 45. https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/ugrad_theses/45 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Works at ScholarWorks@Bellarmine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@Bellarmine. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Dissecting the Man of Steel: The Evolution of Superman as a Reflection of American Society by Marie Gould Advisor: Dr. Aaron Hoffman Readers: Dr. Casey Baugher Dr. Kathryn West 1 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Introduction 2 Objectives 4 Methodology 4 Chapter 1: Creation Years (1938-1939) 6 Chapter 2: World War II (1941-1945) 12 Chapter 3: The 50s and 60s (1950-1969) 17 Chapter 4: The 70s and 80s (1970-1989) 22 Chapter 5: The 90s and 2000s (1990-2010) 27 Conclusion 31 Bibliography 33 2 Abstract Since his debut during the Great Depression in 1938, Superman has become an American cultural icon. His symbol is not only known throughout the nation, but the world as well.