The Cock Fight ”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 No. F. 1-73/2011-Sch.1 Government of India Ministry of Human

No. F. 1-73/2011-Sch.1 Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education & Literacy School-1 Section ***** Dated, 12 th December, 2011 To The Secretary, in-charge of Secondary Education of Jammu & Kashmir. Subject: 19 th meeting of Project Approval Board (PAB) for Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) held on 15 th November, 2011 to consider Annual Plan Proposal 2011-12 of State of Jammu & Kashmir. Sir, I am directed to forward herewith minutes of the 19th meeting of PAB for RMSA held on 15 th November, 2011 to consider Annual Work Plan & Budget (AWP&B) 2011-12 of State of Jammu & Kashmir for information and necessary action at your end. Yours faithfully, (Sanjay Gupta) Under Secretary to the Government of India Encl: - as above Copy to:- 1. EC to Secretary (SE&L) 2. PS to JS & FA 3. PPS to JS (SE-I) 4. VC, NUEPA, New Delhi 5. Chairman, NIOS, NOIDA. 6. Director, NCERT, New Delhi. 7. Sr. Advisor, Education, Planning Commission, New Delhi 1 MINUTES OF THE 19 TH MEETING OF THE PROJECT APPROVAL BOARD (PAB) HELD ON 15 TH NOVEMBER, 2011 TO CONSIDER ANNUAL WORK PLAN AND BUDGET 2011-12 UNDER RASHTRIYA MADHYAMIK SHIKSHA ABHIYAN (RMSA) FOR THE STATE OF JAMMU & KASHMIR, THE PROPOSALS OF NCERT AND REVIEW OF SEMIS IMPLEMENTED BY NUEPA. The 19 th Meeting of the Project Approval Board (PAB) to consider the Annual Work Plan and Budget 2011-12 under Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) for the State of Jammu & Kashmir, the proposals of NCERT and review of submits by NUEPA was held on 15 th November, 2011 at 3.00 p.m. -

Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO

Modified General Merit list of candidates who have applied for admission to B.Ed. prgoramme (Kashmir Chapter) offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir session-2018 Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %age 1 1892469 TABASUM GANI ABDUL GANI GANAIE NAZNEENPORA TRAL PULWAMA OM 1170 1009 86.24 2 1898382 ZARKA AMIN M A PAMPORI BAGH-I-MEHTAB SRINAGAR OM 10 8.54 85.40 3 1891053 MAIDA MANZOOR MANZOOR AHMAD DAR BATENGOO KHANABAL ANANTNAG ANANTNAG OM 500 426 85.20 4 1892123 FARHEENA IFTIKHAR IFTIKHAR AHMAD WANI AKINGAM ANANTNAG ANANTNAG OM 1000 852 85.20 5 1891969 PAKEEZA RASHID ABDUL RASHID WANI SOGAM LOLAB KUPWARA OM 10 8.51 85.10 6 1893162 SADAF FAYAZ FAYAZ AHMAD SOFAL SHIRPORA ANANTNAG OM 100 85 85.00 BASRAH COLONY ELLAHIBAGH 7 1895017 ROSHIBA RASHID ABDUL RASHID NAQASH BUCHPORA SRINAGAR OM 10 8.47 84.70 8 1894448 RUQAYA ISMAIL MOHAMMAD ISMAIL BHAT GANGI PORA, B.K PORA, BADGAM BUDGAM OM 10 8.44 84.40 9 1893384 SHAFIA SHOWKET SHOWKET AHMAD SHAH BATAMALOO SRINAGAR OM 10 8.42 84.20 BABA NUNIE GANIE, 10 1893866 SAHREEN NIYAZ MUNSHI NIYAZ AHMAD KALASHPORA,SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM 900 756 84.00 11 1893858 UZMA ALTAF MOHD ALTAF MISGAR GULSHANABAD K.P ROAD ANANTNAG ANANTNAG OM 1000 837 83.70 12 1893540 ASMA RAMZAN BHAT MOHMAD RAMZAN BHAT NAGBAL GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM 3150 2630 83.49 13 1895633 SEERATH MUSHTAQ MUSHTAQ AHMED WANI DEEWAN COLONY ISHBER NISHAT SRINAGAR OM 1900 1586 83.47 14 1891869 SANYAM VIPIN SETHI ST.1 FRIENDS ENCLAVE FAZILKA OTHER STATE OSJ 2000 1666 83.30 15 1895096 NADIYA AHAD ABDUL AHAD LONE SOGAM LOLAB KUPWARA OM 10 8.33 83.30 16 1892438 TABASUM ASHRAF MOHD. -

Census of India 1981

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES-8 JAMMU & KASHMIR Special Paper of 1981 VILLAGE / TOWN WISE POPULATION AND SCHEDULED CASTE POPULATION ABDUL GANI Joint Dil ector of Census Operations Jammu and Kashmir PREFACE This is a special publication presenting the 1981 Census total popu lation and scheduled caste population of the State, districts and Tehsils down to village/urban block level to meet the requirement of data users interested in figures of population at village/ward level. This requirement could have been served by the 1981 District Census Handbooks which contain comprehensive basic information about populatIon by sex including literacy and work partici pation but the printing and publication of these handbooks which is the respon sibility of the State government will take some time. Until these handbooks are published, it is hoped that the present volume will serve a useful purpose to feed the urgent requirement of all data users. The Director of Census Opserations Shri A. H. Khan, under whose guidance the entire census operations were carried out, deserve all cred it for the success of the operations but he had to leave the organisation because of superannuation before this paper could be made ready for the press. I must record my deepest sense of gratitude to Shri V.S. Verma, Registrar General, India and Shri V.P. Pandey, Joint Registrar General, IndIa for their valuable guidance and for having agreed to bring out this specIal paper even in deviation of the approved census publications programme and arrange for its printing on a priority basis through the Printing Divi~ion of the Registrar General's Office under the supervision of Shri Tirath Dass, Joint Director. -

Minutes of 28Th GIAC Meeting

Scheme I – Financial Assistance for Bulk Purchase of Books ANNEXURE-l List of proposals Recommended in the 28 th Grant in Aid Committee Meeting held on 10 th & 11 th September 2012 Assamese (a) No. of proposals presented-1 (b) No. of proposals Recommended-1 (c) No. of proposals Not Recommended and reasons there of Nil No. of Copies Sl. Name & Address of the Amount ( ```) Title Price ( ```) Recommended No. Applicant & File No. (less discount) & Approved 1 Sri Mitradev Sarma, Nefarpora Rajasthanloi 70/- 200 10,500/- Luitel Bhawan Ward 19, Chandmari, P.O. Tezpur, Sonitpur, Assam-784001. 50-1(1)/11-12/Asm/GIA Total 10,500/- Bengali (a) No. of proposals presented-12 (b) No. of proposals Recommended-9 (c) No. of proposals Not Recommended and reasons there of -3 No. of Copies Sl. Name & Address of the Amount ( ```) Title Price ( ```) Recommended No. Applicant & File No. (less discount) & Approved 1 Dr. Nihar Kanti Mondal, Jiban Anwesha Panchjan Kabi 125/- 150 14063 Mahendra Apartment, 181/2B, Raipur Road, Kolkata-700047. 50-2(7)/11-12/Ben/GIA 2 Dr. Khokan Kumar Bag, Madhyayuger Bangla Sahitye 150/- 150 16875 'Sampan', Badsahi Road, Shiv-Kahini: Upekshiter Katha Bhangakuthi, P.O. & Dsit-Burdwan, West Bengal-713101. 50-2(1)/12-13/Ben/GIA 3 Sri Radhakrishna Yugapurush Raja Rammohan Roy 50/- 200 7500 Goswami, 68, Nabarunpalli, S.P. Mukherjee Road, P.O. Sodepur, 24 Prgs (N), West Bengal-700110. 50-2(8)/11-12/Ben/GIA 4 Dr. Sikha Kundu, Manabdharma Tomar Aaloke 150/- 200 22500 C/o Krishnaraj Debabanimandir, Badanganj-P.O., Hoogly Dist, Westbengal-712122 50-2(21)/10-11/Ben/GIA 5 Dr. -

Dr. Syed Zahoor Ahmad Geelani Dean and Head School of Education Central University of Kashmir [email protected] Phone No: +919419015243

Dr. Syed Zahoor Ahamad Geelani (Dean &Head) School of Education Dr. Syed Zahoor Ahmad Geelani Dean and Head School of Education Central University of Kashmir [email protected] Phone no: +919419015243 Objective To be a 21st-century teacher with high productivity, quality, and professionalism Education 1. NET UGC (Education) 2. Ph. D Education 3. M. Sc. Zoology (Meerut University) 4. M. A Urdu (MANUU) 5. B. Ed (University of Kashmir) 6. M. Ed (University of Kashmir) Experience 1. Dean and Head School of Education, Central University of Kashmir 2. Associate Professor, Department of Teacher Education School of Education CUK 3. Dean, student’s welfare Central University of Kashmir 4. I/C Principal MANUU, Arts and Science College, Budgam 5. Associate Professor (MANUU, CTE Srinagar) 6. Lecturer Bio Science- KCEF College of Education Pulwama 7. Coordinator M Ed (D/M) Kashmir University 8. Resource Person, for B Ed and M Ed Directorate of Distance Education Kashmir University 9. Academic Counsellor, for B Ed Directorate of Distance Education MANUU Hyderabad 10. Greater Kashmir Columnist 11. Coordinator, Ek Bharat Shrestha Bharat, MHRD project imitated by Government of India. Field of Specialization 1. Science Education 2. Information and Communication Technology, 3. Philosophy of Education, 4. Teaching of Bio Science. 5. Teaching of Urdu Dr. Syed Zahoor Ahamad Geelani (Dean &Head) School of Education 1. Geelani. S. A. Z. (2010). Taleemi Technology A book on Educational Books / Technology. Srinagar Jammu and Kashmir: Sayar Publishers., Chapters ISBN-978-93-5087-147-8. in Books 2. Geelani. S. A. Z. (2011). Fundamentals of Counseling and Guidance. -

Registration No

List of Socities registered with Registrar of Societies of Kashmir S.No Name of the society with address. Registration No. Year of Reg. ` 1. Tagore Memorial Library and reading Room, 1 1943 Pahalgam 2. Oriented Educational Society of Kashmir 2 1944 3. Bait-ul Masih Magarmal Bagh, Srinagar. 3 1944 4. The Managing Committee khalsa High School, 6 1945 Srinagar 5. Sri Sanatam Dharam Shital Nath Ashram Sabha , 7 1945 Srinagar. 6. The central Market State Holders Association 9 1945 Srinagar 7. Jagat Guru Sri Chand Mission Srinagar 10 1945 8. Devasthan Sabha Phalgam 11 1945 9. Kashmir Seva Sadan Society , Srinagar 12 1945 10. The Spiritual Assembly of the Bhair of Srinagar. 13 1946 11. Jammu and Kashmir State Guru Kula Trust and 14 1946 Managing Society Srinagar 12. The Jammu and Kashmir Transport union 17 1946 Srinagar, 13. Kashmir Olympic Association Srinagar 18 1950 14. The Radio Engineers Association Srinagar 19 1950 15. Paritsarthan Prabandhak Vibbag Samaj Sudir 20 1952 samiti Srinagar 16. Prem Sangeet Niketan, Srinagar 22 1955 17. Society for the Welfare of Women and Children 26 1956 Kana Kadal Sgr. 1 18. J&K Small Scale Industries Association sgr. 27 1956 19. Abhedananda Home Srinagar 28 1956 20. Pulaskar Sangeet Sadan Karam Nagar Srinagar 30 1957 21. Sangit Mahavidyalaya Wazir Bagh Srinagar 32 1957 22. Rattan Rani Hospital Sriangar. 34 1957 23. Anjuman Sharai Shiyan J&K Shariyatbad 35 1958 Budgam. 24. Idara Taraki Talim Itfal Shiya Srinagar 36 1958 25. The Tuberculosis association of J&K State 37 1958 Srinagar 26. Jamiat Ahli Hadis J&K Srinagar. -

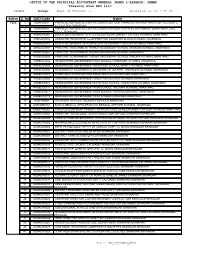

Treasury Wise DDO List Position As on : Name of Tresury

OFFICE OF THE PRINCIPAL ACCOUNTANT GENERAL JAMMU & KASHMIR- JAMMU Treasury wise DDO list Location : Srinagar Name of Tresury :- Position as on : 09-JAN-17 Active S. No DDO-Code Name YES 1 002FIN0001 FINANCIAL ADVISOR & CHIEF ACCOUNTS OFFICER FINANCIAL ADIVSOR AND CHIEF ACCOUNTS OFFICER SGR SRINAGAR 2 003FIN0001 FINANCIAL ADVISOR & CHIEF ACCOUNTS OFFICER O/O FA & CAO FINANCE DEARTMENT CIVIL SECTT. SRINAGAR 3 AHBAGR0001 BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER ACHABAL ANANTNAG 4 AHBAGR0002 ASSISTANT REGISTRAR CO-OPEREATIVE SOCIETIES BLOCK ACHABAL ANANTNAG 5 AHBAHD0001 BLOCK VETERINARY OFFICER BLOCK VETERINARY OFFICER ACHABAL ANANTNAG 6 AHBEDU0001 PRINCIPAL GOVERNMENT HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL AKINGAM ACHABAL ANANTNAG 7 AHBEDU0002 PRINCIPAL GOVERNMENT HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL ANANTNAG 8 AHBEDU0003 PRINCIPAL GOVERNMENT HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL HAKURA ACHABAL ANANTNAG 9 AHBEDU0004 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL HARDPORA ACHABAL ANANTNAG 10 AHBEDU0005 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BRINTY ACHABAL ANANTNAG 11 AHBEDU0006 HEADMASTER HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT SCHOOL THAJIWARA ACHABAL ANANTNAG 12 AHBEDU0007 ZONAL EDUCATION OFFICER ZONAL EDUCATION OFFICER ANANTNAG 13 AHBEDU0008 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL ACHABAL ANANTNAG 14 AHBEDU0009 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT BOYS HIGH SCHOOL GOPALPORA ACHABAL ANANTNAG 15 AHBEDU0010 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL TAILWANI ACHABAL ANANTNAG 16 AHBEDU0011 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL TRAHPOO DISTRICT ANANTNAG 17 AHBEDU0012 HEADMASTER GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL RANIPORA ANANTNAG 18 AHBFIN0001 -

ANNUAL PLAN of SSA 2005-06 DISTRICT PULWAMA.Pdf

S.No. CONTENTS Page No. 1. Introduction 3 2. District Profile 6 3. Educational Profile 15 4. Objective and goals of SSA 19 5. Planning Process 20 6. Problems and Issues 33 7. Problems Strategies and interventions 37 8. Achievements under Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan 41 9.1 Convergence and Linkage 47 10. Quality Intervention 49 11. Special Focus group 58 12. Community Participation and community moblisation 69 13. Research, Supervision and monitoring 74 14. Civil Works 76 15. NPEGEL 82 16. Budget 96 17. Tables 101 Chapter-I INTRODUCTION ANNUAL WORK PLAN & BUDGET FOR 2005-06 Planning is the process througli which we determine the goals, devise the strategies and identify the resources and try to make the best use of such resources to achieve our goal within a given time frame, e.g, under SSA we have the target of universal access and universal enrolment for 6-14 age group, by the year 2005, then Universal retention to facilitate universal primary education by the year 2007 and universal upper primary education by the year 2010. We again have the target of imparting quality education to the children to ensure their rising achievement graph. To achieve these prime objectives, within the given time frame we have devised strategies and interventions for example to ensure universal access to children within 6-14 age group , we provide a net work of schools to areas that do not have the schools, but where the norms of opening of such schools are fully satisfied. In areas that don’t satisfy these norms but fall outside the radius of 1 BCm. -

Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO

Updated General Merit List of candidates who have applied for admission to MA/M.Sc Mathematics programme offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir session-2018 Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %age 1 18272837 JAVID AHMD BEIGH GULLAH BEIGH SHANIPORA KHANSAHIB BUDGAM RBA 1800 1009 56.06 TANGMARG D.H PORA KULGAM- 2 18272838 MUZAFAR AHMAD JEHRA NAZIR AHMAD JEHRA 192233 KULGAM ST 1000 683 68.30 3 18272839 SHAHID LATEEF LATEEF AHMAD HAWAL,RANGA MASJID,SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM 10 7.94 79.40 4 18272841 MOHAMMAD YOUNESS BHAT ABDUL RAHIM BHAT MALOORA SRINAGAR OM 100 70 70.00 GULABAD COLONY ARMPORA 5 18272846 UMAR SABIR MOHD SABIR TELI SOPORE BARAMULLA WUP 1800 1045 58.06 PATI JATHAR KACHUMUQAM 6 18272850 NIMRAH SHAKEEL SHAKEEL AHMAD BAIG BARAMULLA BARAMULLA OM 1800 929 51.61 7 18272857 HILAL AHMAD MIR ABDUL AHAD MIR LANGATE HANDWARA KUPWARA KUPWARA OM 1800 922 51.22 8 18272865 RAFIA JAN GH NABI DAR DALWACH QAZIGUND ANANTNAG RBA 1800 925 51.39 9 18272867 NUSRAT HASSAN GH HASSAN MALIK QADERNA MARWAH KISHTWAR RBA 1800 890 49.44 10 18272870 ZAKIR HUSSAIN MOHD RAMZANBOHRU DOLIGAM BANIHAL RAMBAN RBA 1800 1192 66.22 11 18272871 MUSHARIBA ALTAF MIR ALTAF HUSSAIN WANDEVALGAM KOKERNAG ANANTNAG RBA 2400 1488 62.00 12 18272874 AYAZ AHMAD KUMAR ABDUL RAHIM KUMAR BEHRAMPORA RAFIABAD BARAMULLA OM 1800 1098 61.00 13 18272885 SOZIYA MUSHTAQ MUSHTAQ AHMAD LONE KAKAPORA PULWAMA OM 1800 1067 59.28 14 18272886 RAOUF AHMAD GANAI GULL MOHD GANIE TAILWANI ACHABAL ANANTNAG ANANTNAG OM 1800 884 49.11 15 18272897 IRTISHA -

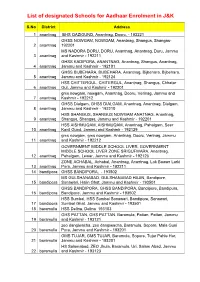

List of Designated Schools for Aadhaar Enrolment in J&K

List of designated Schools for Aadhaar Enrolment in J&K S.No District Address 1 anantnag BHS QAZIGUND, Anantnag, Dooru, - 192221 GHSS NOWGAM, NOWGAM, Anantnag, Shangus, Shangas- 2 anantnag 192201 MS NADORA DORU, DORU, Anantnag, Anantnag, Duru, Jammu 3 anantnag and Kashmir - 192211 GHSS KADIPORA, ANANTNAG, Anantnag, Shangus, Anantnag, 4 anantnag Jammu and Kashmir - 192101 GHSS BIJBEHARA, BIJBEHARA, Anantnag, Bijbehara, Bijbehara, 5 anantnag Jammu and Kashmir - 192124 HSS CHITTERGUL, CHITERGUL, Anantnag, Shangus, Chhatar 6 anantnag Gul, Jammu and Kashmir - 192201 gms nowgam, nowgam, Anantnag, Dooru, Verinag, Jammu and 7 anantnag Kashmir - 192212 GHSS Dialgam, GHSS DIALGAM, Anantnag, Anantnag, Dialgam, 8 anantnag Jammu and Kashmir - 192210 HSS SHANGUS, SHANGUS NOWGAM ANATNAG, Anantnag, 9 anantnag Shangus, Shangas, Jammu and Kashmir - 192201 HSS AISHMUQAM, AISHMUQAM, Anantnag, Pahalgam, Seer 10 anantnag Kanil Gund, Jammu and Kashmir - 192129 gms nowgam, gms nowgam, Anantnag, Dooru, Verinag, Jammu 11 anantnag and Kashmir - 192212 GOVERNMENT MIDDLE SCHOOL LIVER, GOVERNMENT MIDDLE SCHOOL LIVER ZONE SRIGUFWARA, Anantnag, 12 anantnag Pahalgam, Lewar, Jammu and Kashmir - 192126 ZONE ACHABAL, Achabal, Anantnag, Anantnag, Lok Bawan Larki 13 anantnag Pora, Jammu and Kashmir - 192211 14 bandipora GHSS BANDIPORA, - 193502 MS GULSHANABAD, GULSHANABAD HAJIN, Bandipore, 15 bandipora Sonawari, Hajin Ghat, Jammu and Kashmir - 193501 GHSS BANDIPORA, GHSS BANDIPORA, Bandipore, Bandipura, 16 bandipora Bandipore, Jammu and Kashmir - 193502 HSS Sumbal, HSS Sumbal -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :RURAL STATE : JAMMU & KASHMIR DISTRICT : Anantnag Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 SELFHELF GROUP ZAMALGAM ZAMALGAM HALRA BATAGOND B BLOCK SHAHABAD , PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL 2000 10 - 50 GULARBASTI DAIRY NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 2 SHAHHI HANDAN SELF HELP GROUP SAKHRAS PAHALGAM ANANTNAG JAMMU&KASHMIR PIN CODE: 192401, STD CODE: NA , TEL 2002 10 - 50 SAKHRAS NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 3 SHEEP FORM AT DAKSUM , , PIN CODE: 192202, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 2000 51 - 100 NIC 2004 : 0122-Other animal farming; production of animal products n.e.c. 4 GOVT SERICULTURE NURSERY VESSU GOVT SERICULTUR , PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : 1957 10 - 50 N.A. NIC 2004 : 0140-Agricultural and animal husbandry service activities, except veterinary activities. 5 GRASSLAND AND FOODER SIRHAMA BIJBEHARA ANANTNAG JAMMU &KASHMIR , PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL 1986 10 - 50 DEVEOPMENT STATION NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 6 AGRICULTURE FARM AROO , PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 1988 10 - 50 7 MOHD ASHRAF SOORVERDI EXTENTION OFFICER MONIGAM TEH. KULGAM DISTT. ANANTNAG JAMMU AND KASHMIR PIN 1989 10 - 50 AGRICULTURE CODE: 192231, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. -

R&B Kashmir Full

Page No 1 Detail of Junior Engineer of R&B Circle Baramulla / Kupwara Jurisdiction of Junior Engineer S. Name of Name of JE's Road ‐ No. Division Roads Length in Buildings Bridges Mobile No. KM R&B Division Baramulla 30mtr. Span bridge at Sheeri Hewan Malpora Larridora Road 1‐10.5 RAMSA Building at Audoora Audoora PHC Sheeri (Addl. Zandfaran Audoora Namblan Road 1‐8 ‐ Accomodation) Unani Dispensary at Nowgam Fathgarh Baramulla Inner Links Km 2.5 ‐ under BADP R&B Div. Er. Tufail Ahmad 1 Heevan‐Kaliban‐Latifabad road Km 7.5 Food godown at Sultanpora ‐ 9906597511 Baramulla Beigh Malpora Audoora Road ANM Building at Bandiballa ‐ Malpora Kawhar Road Km 3.5 ‐ ‐ Baramulla Baba Reshi Sahib Road Km 11‐22 ‐‐ Wahidina Shirpora Road Km 4 ‐‐ Mukam‐ Kohilina Road Km 4 ‐‐ Gantmullah inner links ‐‐ Choora Kreeri Road Km 7 ‐‐ Authoora Saloosa Thandam Road Km 6 ‐‐ R&B Div. Er. Hafizullah 2 Vizer Watergam road Km 4 ‐‐9469103165 Baramulla Baba Bulgam Chandkoot with allied links km 4 ‐‐ Boos‐Poshnaag Road km 4 ‐‐ HSS building at Wagoora Wagoora Hr. Sec Bridge R&B Div. Er. Zubair‐ul Pothkah Kalantra up to Dandmoh with 3 PHC Building Wagoora Shrakwara Vizzer Bridge 9419004973 Baramulla Hassan adjoining links at Wagoora km 15.5 Shrakwara Saloosa ‐ Bridge Delina Singhpora Katiawari road Km 10 ‐‐ Kanispora‐Singhpora‐Khurshi road Km 4 ‐‐ Nowpora‐Najibhat Chandoosa road km 10 ‐‐ R&B Div. Er. Manzoor 4 Singhpora‐Mirahgund road Km 2 ‐‐7298022158 Baramulla Ahmad Sumji Nowpora‐Khaiutangan‐Chandoosa road Km 15 ‐‐ Khaitangan Dardpora road Km 4 ‐‐ Shrakwara Khaitangan Road Km 2.5 ‐‐ Tapper Kreeri Kalantra road Km 15 ‐‐ Page No 2 Jurisdiction of Junior Engineer S.