How Attorneys Judge Collegiate Mock Trials Ruth R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IOWA LAWYER CONTENTS Volume 66 Number 6 June 2006 President’S Letter: Sail Away – Salvo

IOWAIOWATHETHE LAWYER LAWYERVVolumeolume 66 Number 6 June 2006 Marion Beatty takes leadership reins June 22 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE – Iowa team wins high school mock trial national championship – ISBA endorses new professional liability insurance broker – New attorneys join Iowa legal ranks – Arbitrating employment claims: Watch out for these traps – Improving access to justice THE IOWA LAWYER CONTENTS Volume 66 Number 6 June 2006 President’s Letter: Sail away – Salvo . 5 to justice – Toresdahl . 14 Published at 521 East Locust Marion Beatty takes leadership reins . 7 Amendments to articles of incorporation 15 Des Moines, Iowa 50309 Special welcome (photo) . 9 Ag law website available . 16 Steve Boeckman, Editor Iowa’s Valley High School wins College Mock Trial tournament 515-243-3179 national title . 10 – Hoffman-Simanek . 17 ISBA endorses new professional YLD President’s Letter – Preston . 18 liability broker . 11 Leadership Circle . 19 Bridge the Gap prize winners (photo) . 12 Transitions . 20 Law Day activity (photo) . 13 Annual Report to members . Centerspread THE IOWA STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Seventy eight new attorneys join ranks . 13 CLE calendar . 45 OFFICERS 2004-2005 Taking steps to improve access Watch out for these traps in President, J. C. Salvo employment law – Harty . 53 President-elect, Marion Beatty Vice President, Joel Greer Around the Bar Immediate Past President, Nicholas Critelli, Jr. Dinner honors Streits . 54 Executive Director, Dwight Dinkla Canadian Consulate pays a visit (photo) 55 Blink THE IOWA LAWYER On shutting it out – . 56 (ISSN 1052-5327) is published monthly by The Iowa State Classified Ads . 57 Bar Association, 521 East Locust, Des Moines, Iowa 50309. -

Steps in a Mock Trial

STEPS IN A MOCK TRIAL 1. The Opening of the Court Either the Clerk of the Court of the judge will call the Court to order. When the judge enters, all the participants should remain standing until the judge is seated. The case will be announced, i.e., "The Court will now hear the case of vs. ." The judge will then ask the attorney for each side if they are ready. A representative of each team will introduce and identify each member of the team and the role each will play. 2. Opening Statement (1) Prosecution (in criminal cases) Plaintiff (in civil cases) The prosecutor in a criminal case (or plaintiff' s attorney in a civil case) summarizes the evidence which will be presented to prove the case. (2) Defendant (in criminal or civil case) The defendant' s attorney in a criminal or civil case summarizes the evidence for the Court which will be presented to rebut the case the prosecution has made. 3. Direct Examination by Plaintiff The prosecutors (plaintiff' s attorneys) conduct the direct examination of its own witnesses. At this time, testimony and other evidence to prove the prosecution' s (plaintiff' s) case will be represented. The purpose of direct examination is to allow the witness to state the facts in support of the case. Note: The attorneys for both sides, on both direct and cross examination, should remember that their only function is to ask questions; attorneys themselves may not testify or give evidence, and they must avoid phrasing questions in a way that might violate this rule. -

Minneapolis, Minnesota Regional Tournament February 1-3, 2013 Hosted by Hamline University Official Tabulation Room Summary

AMERICAN MOCK TRIAL ASSOCIATION Minneapolis, Minnesota Regional Tournament February 1-3, 2013 Hosted by Hamline University Official Tabulation Room Summary Team/School Round 1 Round 2 Round 3 Round 4 Summary 1010 ! v. 1136 " v. 1334 " v. 1409 ! v. 1148 6 - 2 - 0 Univ. of Wisconsin Superior W W W W W L L W CS OCS PD 13 12 30 17 7 -15 -8 7 16 78 63 1011 ! v. 1086 " v. 1625 ! v. 1601 " v. 1347 3 - 5 - 0 Univ. of Wisconsin Superior L L W L L L W W CS OCS PD -6 -11 3 -4 -13 -13 10 14 13.5 61 -20 1065 " v. 1235 ! v. 1148 ! v. 1625 " v. 1174 3 - 5 - 0 St. Norbert College L L W L W W L L CS OCS PD -18 -12 6 -7 14 34 -3 -9 13 65 5 1066 ! v. 1334 " v. 1136 ! v. 1347 " v. 1625 3 - 5 - 0 St. Norbert College L L L L L W W W CS OCS PD -7 -1 -27 -13 -7 8 20 23 8 67.5 -4 1086 " v. 1011 ! v. 1587 " v. 1532 ! v. 1600 7 - 0 - 1 Macalester College W W T W W W W W CS OCS PD 6 11 0 5 11 8 5 3 16.5 65 49 1087 " v. 1148 ! v. 1235 " v. 1600 ! v. 1334 6 - 1 - 1 Macalester College W W W W T L W W CS OCS PD 11 15 8 1 0 -8 20 5 15.5 75.5 52 1136 " v. -

2015 Annual Report

United States District Court District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands 2nd Floor, Horiguchi Building 123 Kopa Di Oru St., Beach Road, Garapan Saipan, MP 96950 2015 ANNUAL United States District Court DISTRICT REPORT District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands 2nd Floor, Horiguchi Building 123 Kopa Di Oru St. • Beach Road, Garapan • Saipan, MP 96950 Telephone: (670) 237‐1200 • Facsimile: (670) 237‐1201 Internet Address: hp://www.nmid.uscourts.gov February 6, 2016 16 2016 Ninth Circuit Civics Contest: The NMI District Court and the Ninth FOREWORD Circuit courts and Community Commiee is sponsoring an essay and video contest for high school students in the NMI. C J The NMI District Court will conduct preliminary judging for the contest. The top three finishers in the essay and video R V. M compeons at the district level will go on to compete in the Ninth Circuit contest. To be eligible students must reside in the NMI. More informaon on the contest is available at: The release of this annual report to coincide with the yearly district court hp://www.cap9.uscourts.gov/civicscontest conference provides an opportunity to reflect on last year’s district conference as well as the challenges and the achievements of the court from February 2015 through January 2016. Last February’s conference, entled “Warriors or Lawyers? Ethics and Professionalism,” focused on how lawyers can maintain a high standard of ethical pracce while vigorously advocang for their clients’ interests. The Honorable M. Margaret McKeown of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals examined the process of achieving the client’s goals ethically from the UPDATE ON THE NEW COURTHOUSE perspecves of the bench and the bar, and gave a lively presentaon on the On June 29, 2015, the General Services Administraon (GSA) announced the ethical pialls for lawyers and judges using social media. -

The American Mock Trial Association New Team Handbook Online Version

The American Mock Trial Association New Team Handbook Online Version (for 2020-21) 2 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………………… 3 a. Mock Trial………………………………………………………………… 4 b. Intercollegiate Mock Trial………………………………………………… 4 c. Benefits of Mock Trial……………………………………………………. 5 Chapter 1: Starting a Team……………………………………………………………. 7 a. University Support ………………………………………………………… 7 b. AMTA Registration ……………………………………………………….. 7 c. Recruiting Team Members…………………………………………………. 8 d. Budgeting and Fundraising………………………………………………… 8 e. Coaching…………………………………………………………………… 9 f. Structure……………………………………………………………………. 9 g. Scheduling and Preparation………………………………………………… 10 h. Course Credit…………………………………………………………… 10 Chapter 2: Summary of AMTA Competition Rules…………………………………… 13 a. Tournaments………………………………………………………………… 13 b. People at a Tournament……………………………………………………... 14 c. Trial Roles: Attorneys, Witnesses, Timekeepers…………………………… 15 d. Tournament Structure………………………………………………………. 18 Chapter 3: Practicing for Competition………………………………………………… 26 a. Accessing the Case Material……………………………………………….. 26 b. Parts of the Case…………………………………………………………… 26 c. Reading the Case: Developing a Theory and Theme……………………… 28 d. Selecting Witnesses………………………………………………………… 31 e. Practicing…………………………………………………………………… 31 f. Public Speaking……………………………………………………………. 32 g. Spirit of AMTA……………………………………………………………. 33 Chapter 4: Trial Skills…………………………………………………………………. 34 a. Pretrial……………………………………………………………………… 34 b. Opening Statement…………………………………………………………. 34 c. Direct Examination………………………………………………………… -

Law & Advocacy Washington, DC

National Student Leadership Conference Law & Advocacy Washington, D.C. Program Overview & Sample Daily Schedule While not every session is scheduled exactly the same, the following Program Overview & Sample Daily Schedule are designed to give you a better understanding of the activities in a typical session as well as the flow of a typical day. Program Overview Day 1 Day 5 • Registration • Lecture: Direct and Cross Examinations • Campus Tours • Trial Section; Witness Preparation • Opening Ceremony • Leadership Series: Negotiation • TA Group Orientation/Trial Section Orientation • Capitol Hill and Smithsonian Institution o Congressional Visits Day 2 o Library of Congress • Leadership Challenge Course o Air and Space Museum • Leadership Series: Personality Styles & Group o National Gallery of Art Dynamics o American History Museum • Lecture: An Overview / The Laws of Homicide o And many more • Trial Section: Understanding the Law • Social: Movie Night • Social: Pizza Night Day 6 Day 3 • Visit: U.S. Supreme Court • Visit: U.S. District Attorney’s Office • Guest Speaker • Lecture: Theme of the Case • Leadership Series: Intrapersonal • Leadership Series: Public Speaking Communication • Visit Historic Georgetown • TA Presentation: Witness Preparation • Lecture: Federal Rules of Evidence & • Trial Section: Objection Drills Evidentiary Procedure • Lecture: Closing Arguments • Trial Section • Ice Cream Social Day 7 • Visit: International Spy Museum Day 4 • • Lecture: Opening Statements Strategy Session: Defense & Prosecution • Guest Speaker: Ethics -

Mock Trials and Hearings, and Statewide Diversion Program, Also in 1991, Iowa LRE Coordinator Tim Buzzell Reported on a Hear Guest Speakers

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. o WORLD .. n .. II tit II N ICE L 144425 U.S. Department of Justice Nationaiii'lstitute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from !r.e person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this II fill • f material has been granted b)l:l • • / / ~u~ 1C Doma1n OJP OJJDP • U.S. Department of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the IJII!!IIIiPIt owner. c m pi - ~Y1ission: to promote il1creased opportunities for citizens to ........... learn about the 1m; and the leaal system. NICEL he National Institute for Citizen Education in the Law (NICEL) 711 G Street. SE Tis a nonprofit organization dedicated to empowering citizens Washington. DC 20003-2861 Voice: (202) 546-6644 through law-related education. LRE is a unique blending of 'IT: (202) 546-7591 substance and strategy: students learn substantive information Fax: (202) 546-6649 about laws, the legal system, and their rights and responsibili tie::. through strategies that promote cooperative learning, critical thinking, and positive interaction between young people and adults. Wnat People Are Saying about NICEL: The Street Law Program has proven very effective in educating children and youth regarding the law and I am pleased that Yale Law School was involved in it early on. -

Organization Space Quantity

SB18-33 A Bill of Recommendations for Contracted Independent Organizations Space Allocations for 2018-2019 Sponsored By: Ty Zirkle (Vice President for Organizations) and Chi Chan (Representative, CLAS) WHEREAS: The Vice President for Organizations oversees the assignment of all storage areas and filing spaces made available to Contracted Independent Organizations by the University; THEREFORE BE IT. ENACTED: The following Contracted Independent Organizations be granted access to the following storage spaces in Newcomb Hall for the 2018 - 2019 year with the full support of the Student Council Representative Body: Organization Space Quantity th Relay for Life at UVA 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th The Navigators 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Club Swim 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Inter-Sorority Council at the University of Virginia 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Queer Student Union 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Circle K International 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Futures in Fashion Association 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th The Human-Animal Support Services at UVA 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Hackers@UVA 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th CVille Solar Project 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers at UVA 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Charlottesville Debate League 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Vietnamese Student Association 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Rhapsody Ballet Ensemble 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Kinetic Sound 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Arab Student Organization 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Persian Cultural Society 5 FLOOR Wardrobe 1 th Hoo Crew 5 -

Page 1 N O V E M B E R 1 2 , 2 0 1 9 Q U O T E O F T H E D a Y

N O V E M B E R 1 2 , 2 0 1 9 Q U O T E O F T H E W O C C E V E N T S D A Y “The sacred is not in heaven or far TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 19 away. It is all around us, and small UPCOMING VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITY: DRESS FOR SUCCESS TRIANGLE human rituals can connect us to its 12:30 PM | Dress for Success Durham presence. And of course, the greatest challenge (and gift) is to Our next WOCC event is a service opportunity with Dress for Success on see the sacred in each other.” Tuesday, November 19 at 1:30pm-2:30pm. We will be assisting local women to - Alma Luz Villanueva create LinkedIn profiles! We are currently waiting to hear from the organization to confirm the number of participants signed up for the workshop. If you can commit to volunteering 1 hour of your time, please sign up here. If you need any help coordinating transportation, please email Garmai Gorlorwulu at [email protected]. Please see the attached flyer for event details. WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 20 Duke Womxn of Color Collective Student & Faculty/Staff Luncheon 12:30 PM | Law School Third Floor Mezzanine WOCC warmly invites students to get to know and mingle with some of the amazing womxn of color faculty and staff at Duke Law. This lunch will be an opportunity for WOC across Duke Law school to enjoy themselves and network with each other. We would love to see you there! For more information, please see the attached flyer or contact Ana Maganto Ramirez at [email protected]. -

2022 Team Power Rankings

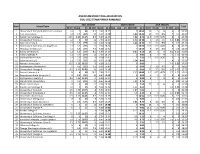

AMERICAN MOCK TRIAL ASSOCIATION 2021-2022 TEAM POWER RANKINGS 2021 SEASON 2020 SEASON 2019 SEASON Rank School/Team Total 36 CH 36 Adj x5 36 ORC 36 Adj x2.5 N/A N/A x3 2020 ORC x1.5 35 CH 35 Adj x1 35 ORC x0.5 1 University of Maryland, Baltimore County A 14 7 35 8.5 5.67 14.17 7 10.50 10 5 5 6 3 50.50 2 Yale University A 13 6.5 32.5 10 6.67 16.68 6.84 10.26 13 6.5 6.5 7 3.5 49.26 3 Patrick Henry ColleGe A 12.5 6.25 31.25 8.5 5.67 14.17 5.84 8.76 11.5 5.75 5.75 6 3 45.76 4 University of Florida A 12 6 30 11 7.34 18.34 6.92 10.38 5 2.5 2.5 6.5 3.25 43.63 5 Duke University A 11 5.5 27.5 10 6.67 16.68 6.84 10.26 11 5.5 5.5 7 3.5 43.26 6 University of California, Los AnGeles A 11 5.5 27.5 11 7.34 18.34 7 10.50 10.5 5.25 5.25 8 4 43.25 7 Wesleyan University A 11 5.5 27.5 7.5 5.00 12.51 7 10.50 9 4.5 4.5 7 3.5 42.50 8 Emory University A 11 5.5 27.5 8.5 5.67 14.17 6.09 9.14 10 5 5 6.5 3.25 41.64 9 Tufts University A 11 5.5 27.5 11 7.34 18.34 6 9.00 8 4 4 7.5 3.75 40.50 10 Stanford University A 11 5.5 27.5 9 6.00 15.01 5 7.50 7.5 3.75 3.75 6 3 38.75 11 Duke University B 11 5.5 27.5 10 6.67 16.68 5.34 8.01 4 2 37.51 12 Harvard University A 10.5 5.25 26.25 9 6.00 15.01 6 9.00 4.5 2.25 37.50 13 Northwestern University A 9 4.5 22.5 9.5 6.34 15.84 6 9.00 9 4.5 4.5 6 3 36.00 14 University of ChicaGo A 8.5 4.25 21.25 10 6.67 16.68 6 9.00 11 5.5 5.5 6.5 3.25 35.75 15 Boston University A 8 4 20 10.5 7.00 17.51 7.25 10.88 9.5 4.75 4.75 7.5 3.75 35.63 16 Pennsylvania State University A 9 4.5 22.5 10 6.67 16.68 6 9.00 4 2 2 6 3 34.50 17 Northwood Univeristy -

2021 Mock Trial Problem

Illinois State Bar Association 424 South Second Street, Springfield, IL 62701 800.252.8908 217.525.1760 Fax: 217.525.0712 Illinois State Bar Association High School Mock Trial Invitational 2021 Mock Trial Case People of the State of Illinois v. Jordan Markson None of the characters in this case are real. Any similarity between these characters and living people is coincidental and unintentional. This problem is based on a problem prepared by the Wisconsin Bar Association and is used with its generous permission. Any requests for use of this problem must be directed to the Wisconsin Bar Association, in addition to the Illinois State Bar Association. Special thanks to ISBA staff personnel, the members and associate members of the ISBA’s Standing Committee on Law-Related Education for the Public, the Mock Trial Coordinator, Katy Flannagan, and Deputy Coordinator, Kelsey Chetosky for their assistance in preparing the problem. © Copyright 2020 Illinois State Bar Association AVAILABLE WITNESSES Prosecution Witnesses Defense Witnesses Blake Stevens Jordan Markson, Defendant Avery Peters Dr. Taylor Smith Dr. Alex McDonnell Drew Davis CASE DOCUMENTS Legal Documents 1. Grand Jury Indictment 4. Jury Instructions 2. Relevant Statutes and Law 5. Pretrial Order 3. Illinois Criminal Code Exhibits 1. CV of Dr. Taylor Smith 2. CV of Dr. Alex McDonnell 10. Police Report 3. Lincoln County Laboratory Report 11. Photo of Crime Scene 4. Lincoln Community Medical Center 12. Photo of Crime Scene Report 13. Photo of Crime Scene 5. Call Detail Report of 911 Call 14. Photo of Crime Scene 6. Text messages 15. Photo of Crime Scene 7. -

Call to Action Here

October 19, 2020 Dear Dean Goluboff, UVA Law administrators, and the greater UVA Law community: We, the members of the Black Law Students Association at UVA Law, along with a coalition of our peer organizations, call for swift and holistic action to create a more inclusive and dynamic environment for current and future Black students, faculty, and staff. As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of UVA BLSA’s founding, we are deeply reflective of the rich history of advocacy that precedes us and the foundation on which we stand. Over this half century, UVA BLSA has led several initiatives to increase Black student enrollment and faculty presence at the law school. Our unwavering commitment to equity, inclusion, and community pushes us to revisit our previous calls for transformative initiatives and substantive change. We find it appropriate and important to notify you of the positive changes made since our last statement: ● Renamed Withers-Brown Hall to Brown Hall in the law school ● Recruited and included a group of students in the faculty interviewing process ● Increased numbers and availability of courses that directly address or are focused on racial justice to be held during this academic year ● Created and hosted more institutionally sponsored events focused on racial justice ● Increased career service outreach, accessibility, and resources for Black and minority students We are encouraged by this progress but acknowledge that this is by no means the end of our work. To that end, we look forward to continuing to work with the administration and the greater UVA Law community to achieve our goals.