1 the Correspondence of Thomas Hobbes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Earl of Lincoln

46S DUKES OF NJ:Wf:ASTU:,. marriage he resided at Hougbton, (vide P• 432,)' but he after wards removed to Welbeck, where he died in 17ll, when, for want of issue, his titles became extinct ;. but be bequeathed his estates to his sister's son, Thomas Pelham,. second Baron Pel- ..ham, of Laughton, in Sussex, who assumed the name of Holles, and in 1714, was created Duke of Newcastle-upon- Tyne, and in 1715, Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyme. At his death in 1768J all his titles became extinct, except those of Duke of New castle-under-Lyme, and Baron Pelham, of Stanemere, which des.t.-ended in marriage with his niece Catharine, to Hem'!} Fiennes Clinton, ninth Earl of Lincoln, who assumed the name 'Of Pelharn, and died in 1794~ His son, Thomas Pelham Clin ton, the late Duke, died in the following .rear, and was suc ceeded by his son, the present most Nohle Henry Pelham · F1ennes-Pelham Clinton, Duke of Newcastle, Earl of Lincoln, Lord Lieutenant of Nottinghamshz"re, K. G., ~c. ~c. whose son, the Right Hon. Henry Pelham Clinton, bears his father's secondary title of Earl of Lincoln, and resides with him at Clumber House. Thefamz'ly of Clinton, wiw now inherit the Clumber portion t>f the Cavendish estates, (vide p. 433,) is of Norman origin, and settled in England at the Conquest. They took their name from the Lordship of Climpton, in Oxfordshire. Roger Climp~ ton or Clinton was Bishop of Coventry, from 1228 till 1249 . .John de Clinton was summoned to Parliament in the first o£ Edward I., by the title of Baron Clinton, of Maf.l'wch. -

W.E. Gladstone Exhibition Boards

W.E. Gladstone The Grand Old Man in Nottinghamshire William Ewart Gladstone (1809-98) was probably the most famous political figure of the nineteenth century. Initially a Conservative, he became a committed Liberal and served as Prime Minister of Britain and Ireland four times between 1868 and 1894. He was popularly known as ‘The People’s Illustration of the ceremony, from Illustrated London News, William’, and, in later life, as the ‘Grand Old Man’, vol. 71, 6 October 1877. or more simply as ‘G.O.M.’ W.E. Gladstone from Thomas Archer, William Ewart Gladstone and his contemporaries (1898), vol. 1 (University Special Collection DA563.4.A7). Born in Liverpool of Scottish ancestry, Gladstone died at his wife’s family home in Hawarden, Wales, but Nottinghamshire was the location of his earliest political success and retained a special interest for him throughout his life. This exhibition commemorates the bicentenary of Gladstone’s birth on 29 December 1809. It demonstrates the diversity of Gladstone’s links with the county and the city of Nottingham, and uses local material to illustrate a few of the themes that engaged Gladstone in his political career. Description of the laying of the foundation stone of University College, from Illustrated London News, vol. 71, 6 October 1877. Ticket of admission to hear Gladstone speak at Alexandra Rink Extract from Gladstone’s speech, (University East Midlands Special from Nottingham Daily Journal, 28 Collection Not 3.F19 NOT O/S X). September 1877. A ceremony of special significance for Nottingham and the University took place in September 1877, when the foundation stone of University College, Nottingham was laid. -

The Cavendishes and Ben Jonson

This is a repository copy of The Cavendishes and Ben Jonson. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/170346/ Version: Published Version Book Section: Rutter, T. orcid.org/0000-0002-3304-0194 (2020) The Cavendishes and Ben Jonson. In: Hopkins, L. and Rutter, T., (eds.) A Companion to the Cavendishes. Arc Humanities Press , Leeds , pp. 107-125. ISBN 9781641891776 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ A COMPANION TO THE CAVENDISHES Companions Arc Humanities’ Reference Works bring together the best of international research in alike. Topics are carefully selected to stand the test of time and, in the best cases, these worksauthoritative are consulted edited for collections decades. that The program have enduring includes benefit historical, to scholars textual, and and students material source books, readers for students that collate and curate required essays for courses, and our Companions program. Arc’s Companions program includes curated volumes that have a global perspective and that earn their shelf space by their authoritative and comprehensive content, up- to- date information, accessibility, and relevance. -

Building a Family: William Cavendish, First Duke of Newcastle, and the Construction of Bolsover and Nottingham Castles

Chap 5 10/12/04 12:20 pm Page 233 Building a Family: William Cavendish, First Duke of Newcastle, and the Construction of Bolsover and Nottingham Castles Introduction Bolsover Castle, overlooking the Doe Lea valley in Derbyshire, and Nottingham Castle, overlooking its city, are among the most dramatic of seventeenth- century great houses. This article proposes an explanation for the re-building of these two medieval castles that is based upon the social circumstances of the family and household responsible for the work. Separated by sixty years, the two buildings appear to be very different yet share the same remarkable patron. William Cavendish (1593–1676) became Viscount Mansfield, then Earl, Mar- quis and finally Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne.1 He is celebrated for his extrav- agant entertainments for Charles I in 1633 and 1634 and his governorship of Prince Charles, the future Charles II. In 1618, he married a local heiress, Elizabeth Bassett, who became the mother of his children before dying in 1643. William was commander of the king’s army in the north during the Civil War and went into exile for fifteen years after losing the battle of Marston Moor in 1644. His second marriage took place in Paris in 1645, to Margaret Lucas, lady in waiting to Henrietta Maria and also a prolific writer.2 He lived in Antwerp, where he wrote his famous book on horsemanship, until 1660. At the Restoration, he returned to live mainly at his family home at Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire until his death in 1676. The Little Castle at Bolsover was begun by William’s father Charles Cavendish (1553–1617) and William himself added interior decoration and further buildings on the site. -

Lewes Parliament 1295–1885

The Parliamentary History of the Borough of Lewes 1295-1885 Wallace H. Hills. Reprinted with additions, from the "East Sussex News." Farncombe & Co., Limited, Lewes, Eastbourne and East Grinstead, 19O8. THE PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY OF THE BOROUGH OF LEWES. Though it began over six centuries ago and came to a termination a little more than a quarter of a century back, the history of the connection of the ancient borough of Lewes with the legisla- tive assembly of the Kingdom has never yet been fully told. It is our intention to give in a plain, and, we trust, a readable form, the full list, so far as it can be compiled from the official and other records, of all the members who have ever been returned to Parliament as representatives of the borough; the dates of election, where such are- known ; some particulars of the several election petitions in which the town has been interested and the contests which have been waged; together with brief biographies of some of those members of whom any record beyond their name remains. First let us briefly show the fragmentary way in which the subject has been dealt with by our county historians and others, in volumes "which are now either rare and costly, or which are not so easily accessible to the " man in the street" as the columns of his weekly journal. In Lee's " History of Lewes " published in 1795, now a very rare book, the author whose name was Dunvan, an usher at a Lewes school, gave, in the seventh chapter, a list of M.P.'s from 1298 to 1473, and in the ninth chapter, a list of those from. -

Slavery Connections of Bolsover Castle, 1600-C.1830

SLAVERY CONNECTIONS OF BOLSOVER CASTLE (1600-c.1830) FINAL REPORT for ENGLISH HERITAGE July 2010 Susanne Seymour and Sheryllynne Haggerty University of Nottingham Acknowledgements Firstly we would like to acknowledge English Heritage for commissioning and funding the majority of this work and the School of Geography, University of Nottingham for support for research undertaken in Jamaica. We would also like to thank staff at the following collections for their assistance in accessing archive material: the British Library; Liverpool Record Office; Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham; the National Library of Jamaica; the National Maritime Museum; Nottinghamshire Archives; and The National Archives. Our thanks are also due to Nick Draper for responding quickly and in full to queries relating to the Compensation Claims database and to Charles Watkins and David Whitehead for information on sources relating to Sir Robert Harley and the Walwyn family of Herefordshire. We are likewise grateful for the feedback and materials supplied to us by Andrew Hann and for comments on our work following our presentation to English Heritage staff in August 2009 and on the draft report. Copyright for this report lies with English Heritage. i List of Abbreviations BL British Library CO Colonial Office LivRO Liverpool Record Office MSCUN Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham NA Nottinghamshire Archives NLJ National Library of Jamaica NMM National Maritime Museum RAC Royal African Company TNA The National Archives -

A Very British Hobbes, Or a More European Hobbes? Patricia Springborga a Centre for British Studies, Humboldt University, Berlin Published Online: 27 Mar 2014

This article was downloaded by: [Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Universitätsbibliothek] On: 31 March 2014, At: 06:33 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK British Journal for the History of Philosophy Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rbjh20 A Very British Hobbes, or A More European Hobbes? Patricia Springborga a Centre for British Studies, Humboldt University, Berlin Published online: 27 Mar 2014. To cite this article: Patricia Springborg (2014): A Very British Hobbes, or A More European Hobbes?, British Journal for the History of Philosophy, DOI: 10.1080/09608788.2014.896248 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09608788.2014.896248 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Appendix 3-3.Pdf

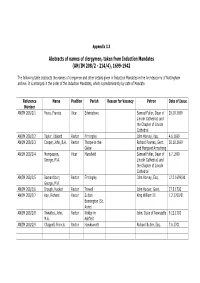

Appendix 3.3 Abstracts of names of clergymen, taken from Induction Mandates (AN/IM 208/2 - 214/4), 1699-1942 The following table abstracts the names of clergymen and other details given in Induction Mandates in the Archdeaconry of Nottingham archive. It is arranged in the order of the Induction Mandates, which is predominantly by date of Mandate. Reference Name Position Parish Reason for Vacancy Patron Date of Issue Number AN/IM 208/2/1 Peete, Francis Vicar Edwinstowe Samuel Fuller, Dean of 26.10.1699 Lincoln Cathedral, and the Chapter of Lincoln Cathedral AN/IM 208/2/2 Taylor, Edward Rector Finningley John Harvey, Esq. 4.6.1699 AN/IM 208/2/3 Cooper, John, B.A. Rector Thorpe-in-the- Richard Fownes, Gent. 30.10.1699 Glebe and Margaret Armstrong AN/IM 208/2/4 Mompesson, Vicar Mansfield Samuel Fuller, Dean of 6.7.1699 George, M.A. Lincoln Cathedral, and the Chapter of Lincoln Cathedral AN/IM 208/2/5 Barnardiston, Rector Finningley John Harvey, Esq. 12.2.1699/00 George, M.A. AN/IM 208/2/6 Brough, Hacker Rector Trowell John Hacker, Gent. 27.5.1700 AN/IM 208/2/7 Kay, Richard Rector Sutton King William III 7.2.1700/01 Bonnington (St. Anne) AN/IM 208/2/8 Thwaites, John, Rector Kirkby-in- John, Duke of Newcastle 9.12.1700 M.A. Ashfield AN/IM 208/2/9 Chappell, Francis Rector Hawksworth Richard Butler, Esq. 7.6.1701 Reference Name Position Parish Reason for Vacancy Patron Date of Issue Number AN/IM 208/2/10 Caiton, William, Vicar Flintham Death of Simon Richard Bentley, Master 15.6.1701 M.A. -

![Bagenall, Bayly, Blackney, Irby, Wallis] ENGLAND, WALES, & IRELAND](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3556/bagenall-bayly-blackney-irby-wallis-england-wales-ireland-6473556.webp)

Bagenall, Bayly, Blackney, Irby, Wallis] ENGLAND, WALES, & IRELAND

182 List of Parliamentary Families PAGET I [Bagenall, Bayly, Blackney, Irby, Wallis] ENGLAND, WALES, & IRELAND Marquess of Anglesey (1815- UK) Origins: Possibly descended from an old Staffordshire family with an MP 1455-61, the Paget origins were obscure. Their fortunes were made by the 1 Baron, the son of a City of London official of small fortune, who became Clerk of the Privy Council 1540, a diplomat, and Secretary of State under Henry VIII. Kt 1543. Baron 1549. First MP 1529. Another MP 1555. A younger son of the 5 Baron Paget went to Ireland. His granddaughter married Sir Nicholas Bayly 2 Bt of Plas Newydd. Their son succeeded to the Paget Barony and was created Earl of Uxbridge. A younger son succeeded to Ballyarthur, Wicklow. 1. Henry Paget 1 Earl of Uxbridge – Staffordshire 1695-1712 2. Thomas Paget – Staffordshire 1715-22 3. Thomas Paget – Ilchester 1722-27 4. Henry Paget 1 Marquess of Anglesey – Caernarvon 1790-96 Milborne Port 1796- 1804 1806-10 5. William Paget – Anglesey 1790-94 6. Air Arthur Paget – Anglesey 1794-1807 7. Sir Edward Paget – Caernarvon 1796-1806 Milborne Port 1810-20 8. Sir Charles Paget – Milborne Port 1804-06 Caernarvon 1806-26 1831-34 9. Berkeley Paget – Anglesey 1807-20 Milborne Port 1820-26 10. Henry Paget 2 Marquess of Anglesey – Anglesey 1820-32 11. Lord William Paget – Caernarvon 1826-30 Andover 1841-47 12. Frederick Paget – Beaumaris 1832-47 13. Lord Alfred Paget – Lichfield 1837-65 14. Lord William Paget – Andover 1841-47 15. Lord Clarence Paget – Sandwich 1847-52 1857-76 16. -

English Heritage Properties 1600-1830 and Slavery Connections

English Heritage Properties 1600-1830 and Slavery Connections A Report Undertaken to Mark the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the British Atlantic Slave Trade Volume One: Report and Appendix 1 Miranda Kaufmann 2007 Report prepared by: Miranda Kaufmann Christ Church Oxford 2007 Commissioned by: Dr Susie West English Heritage Documented in registry file 200199/21 We are grateful for the advice and encouragement of Madge Dresser, University of West of England, and Jim Walvin, University of York Nick Draper generously made his parliamentary compensation database available 2 Contents List of properties and their codes Properties with no discovered links to the slave trade 1 Introduction 2 Property Family Histories 3 Family History Bibliography 4 Tables showing Property links to slavery 5 Links to Slavery Bibliography Appendices 1 List of persons mentioned in Family Histories with entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 2 NRA Listings (separate volume) 3 Photocopies and printouts of relevant material (separate volume) 3 List of properties and their codes Appuldurcombe House, Isle of Wight [APD] Apsley House, London [APS] Audley End House and Gardens [AE] Battle Abbey House [BA] Bayham Old Abbey House, Kent [BOA] Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens [BH] Bessie Surtees House, Newcastle [BSH] Bolsover Castle, Derbyshire [BC] Brodsworth Hall and Gardens [BRD] Burton Agnes Manor House [BAMH] Chiswick House, London [CH] De Grey Mausoleum, Flitton, Bedfordshire [DGM] Derwentcote Steel Furnace [DSF] Great Yarmouth Row Houses [GYRH] Hardwick -

Patrician Landscapes and the Picturesque in Nottinghamshire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham P a g e | 1 PATRICIAN LANDSCAPES AND THE PICTURESQUE IN NOTTINGHAMSHIRE c.1750-c.1850* Richard A Gaunt University of Nottingham Abstract: This article considers the Dukeries estates of north Nottinghamshire in the hey-day of aristocratic power and prestige, from the mid-Georgian to the mid-Victorian period. It poses a contrast between visitors’ impressions of the area as one of constancy and continuity, a point of reassurance in an age of political and social upheaval, and the reality of internal changes from within. Closely crowded as these estates were, their aristocratic owners competed with one another to fashion the most economically viable and aesthetically pleasing symbol of status and power. The article pays close attention to the hold which picturesque principles exercised on individual owners and considers the role of plantation, animals and water in parkland management and improvement. Finally, the article considers the extent to which the estates were sites of contestation; owners attempted to keep unwanted plebeian incursions at bay, whilst carefully controlling access on set-piece occasions such as coming-of-age festivities. Keywords: Patrician, Picturesque, Landscape, Improvement, Romanticism, Toryism P a g e | 2 In September 1832, W. E. Gladstone visited Nottinghamshire for the first time. After spending time in Newark, making preparations for contesting his first parliamentary election, he made his way through Sherwood Forest to Clumber Park, the family seat of his electoral patron, the 4th Duke of Newcastle. Gladstone’s surroundings were apt to make him wax lyrical: The road to Clumber lay through Sherwood Forest, and the fine artless baronial park of Lord Manvers. -

THE DEVONSHIRE CAVENDISHES: POLITICS and PLACE Sue Wiseman

PB Chapter 21 THE DEVONSHIRE CAVENDISHES: POLITICS AND PLACE Sue Wiseman* orth endishes ell us about the ary and political w landha t Cean part the of the Chatsw “pursuit ofCav e andt er” in a aceliter o maintain position.cul- Thatture ofin seventeenth- the case of thecentury Engorthland? Asendishes Mark Girouar the d puts’s it, the dynastic century house and wer pleasur pow r t orth eting orChatsw . Cavor ample, familyy seventeenth-orth enirs e histhe- tormory andof later significance and, are ethe bound serving together l is shownwn in almost an), y itwem ofy modernesent Chatsworth ismark e withsouvenir Fd oex past andman Chatsw. This souvl s ustak a view f tableware— lik bow sho (Figure 21.1 ho the pr theChatsw l utilizessuggestiv spooning depthregar o ert a up present ymmetrical bowview ofshow the açade and aof Williamynoptic Talman’s 1687–y of 1688the ruse.emodelling It cerpts of the or house. the Designedr the for fruit-y serving,y detailsbow of a orth , twingoff a seatclose- of s hill landscape in thef distance shapeds y theiconograph esence of the hohouse, colonnadedex f açade,purchase d dens,ke takeawa , . Chatsw, this peacefulvisit scenesho of aticpower: dominance y be ed with another b pr century e of orthf om designea distancegar that esstatuary in the landscaperiver However ound . Published in lisharistocr in the ear alman ma ed hiscompar emodelling but writtenseventeenth- ear , a poem describesvignett seeingChatsw Chats orthfr in a diff ent cont tak ar it Eng y T complet r lier w er ext: And C orth as a point it doth entwine.