Illustrator in a Web Workflow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microsoft Powerpoint

Development of Multimedia WebApp on Tizen Platform 1. HTML Multimedia 2. Multimedia Playing with HTML5 Tags (1) HTML5 Video (2) HTML5 Audio (3) HTML Pulg-ins (4) HTML YouTube (5) Accessing Media Streams and Playing (6) Multimedia Contents Mgmt (7) Capturing Images 3. Multimedia Processing Web Device API Multimedia WepApp on Tizen - 1 - 1. HTML Multimedia • What is Multimedia ? − Multimedia comes in many different formats. It can be almost anything you can hear or see. − Examples : Pictures, music, sound, videos, records, films, animations, and more. − Web pages often contain multimedia elements of different types and formats. • Multimedia Formats − Multimedia elements (like sounds or videos) are stored in media files. − The most common way to discover the type of a file, is to look at the file extension. ⇔ When a browser sees the file extension .htm or .html, it will treat the file as an HTML file. ⇔ The .xml extension indicates an XML file, and the .css extension indicates a style sheet file. ⇔ Pictures are recognized by extensions like .gif, .png and .jpg. − Multimedia files also have their own formats and different extensions like: .swf, .wav, .mp3, .mp4, .mpg, .wmv, and .avi. Multimedia WepApp on Tizen - 2 - 2. Multimedia Playing with HTML5 Tags (1) HTML5 Video • Some of the popular video container formats include the following: Audio Video Interleave (.avi) Flash Video (.flv) MPEG 4 (.mp4) Matroska (.mkv) Ogg (.ogv) • Browser Support Multimedia WepApp on Tizen - 3 - • Common Video Format Format File Description .mpg MPEG. Developed by the Moving Pictures Expert Group. The first popular video format on the MPEG .mpeg web. -

There Are 2 Types of Files in the Graphics World Bit Mapped (RASTER)

There are 2 Types of Files in the Graphics World Bit Mapped (RASTER) • There are two kinds of computer graphics: Bit Mapped (RASTER) and Object Oriented (VECTOR). Bit mapped graphics are graphics that are stored in the form of a bitmap. They are a sequence of bits that get drawn onto the screen. You create bit mapped graphics using a painting program. • When you enlarge a bit mapped image, you will get a pixelated look. If you are planning to print out an image that was originally 3 inches on 3 inches as 6 inches by 6 inches, you will get a very pixelated look. • Bit mapped graphics tend to create larger files than object oriented graphics. • As you can see from these two pictures, when a bitmapped image gets scaled up, the detail is lost, as opposed to an object oriented drawing where no pixelation occurs. Key Points of Raster Images pixels in a grid resolution dependent resizing reduces quality easily converted restricted to rectangle minimal support for transparency Object Oriented (VECTOR) Definition: Vector graphics are made up of many individual objects. Each of these objects can be defined by mathematical statements and has individual properties assigned to it such as color, fill, and outline. Vector graphics are resolution independent because they can be output to the highest quality at any scale. Software used to create vector graphics is sometimes referred to as object-based editing software. Common vector formats include AI (Adobe Illustrator), CDR (CorelDRAW), CGM (Computer Graphics Metafile), SWF (Shockwave Flash), and DXF (AutoCAD and other CAD software). -

5Lesson 5: Multimedia on the Web

5Lesson 5: Multimedia on the Web Objectives By the end of this lesson, you will be able to: 1.5.7: Download and store files using a Web browser. 1.5.10: Install and upgrade common plug-ins, add-ons and viewers (e.g., Adobe Reader, Adobe Flash Player, Microsoft Silverlight, Windows Media Player, Apple QuickTime) and identify their common file name extensions. 1.5.11: Use document and multimedia file formats, including PDF, PNG, RTF, PostScript (PS), AVI, MPEG, MP3, MP4, Ogg. Convert between file formats when appropriate. 5-2 Internet Business Associate Pre-Assessment Questions 1. Briefly describe C++. 2. Which statement about vector graphics is true? a. Vector graphics are saved as sequences of vector statements. b. Vector graphics have much larger file sizes than raster graphics. c. Vector graphics are pixel-based. d. GIFs and JPGs are vector graphics. 3. Name at least two examples of browser plug-ins. © 2014 Certification Partners, LLC. — All Rights Reserved. Version 2.1 Lesson 5: Multimedia on the Web 5-3 Introduction to Multimedia on the Web NOTE: Multimedia on the Web has expanded rapidly as broadband connections have allowed Multimedia use on users to connect at faster speeds. Almost all Web sites, including corporate sites, feature the Web has been hindered by multimedia content and interactive objects. For instance, employee orientation sessions, bandwidth audio and video memos, and training materials are often placed on the Internet or limitations. Until all Internet users have corporate intranets. high-speed connections Nearly all network-connected devices, such as PCs, tablets, smartphones and smart TVs, (broadband or can view online interactive multimedia. -

Webp/ Content Type Avg # of Requests Avg Size HTML 6 39 Kb Images 39 490 Kb 69% Javascript 10 142 Kb CSS 3 27 Kb

WebRTC enabling faster, smaller and more beautiful web Stephen Konig [email protected] Ilya Grigorik [email protected] https://developers.google.com/speed/webp/ Content Type Avg # of Requests Avg size HTML 6 39 kB Images 39 490 kB 69% Javascript 10 142 kB CSS 3 27 kB HTTP Archive - Mobile Trends (Feb, 2013) @igrigorik It's a HiDPI world... Tablet dimension device-width px/inch Nexus 7 3.75 603 ~ 160 Kindle Fire 3.5 600 ~ 170 iPad Mini 4.75 768 ~ 160 PlayBook 3.54 600 ~ 170 Galaxy 7'' (2nd gen) 3.31 600 ~ 180 Macbook + Retina 15.4 2880 ~ 220 Chromebook Pixel 12.85 2560 ~ 239 HiDPI screens require 4x pixels! Without careful optimization, this would increase the size of our pages by a huge margin - from 500KB to ~2000 KB! Which image format should I use? Wrong question! Instead, what if we had one format with all the benefits and features? ● Lossy and lossless compression ● Transparency (alpha channel) ● Great compression for photos ● Animation support ● Metadata ● Color profiles ● .... That's WebP! Brief history of WebP... ● WebM video format uses VP8 video codec ● WebP is derived from VP8, essentially a key frame... ● Web{P,M} are open-source, royalty-free formats ○ Open-sourced by Google in 2010 ○ BSD-style license ● #protip: great GDL episode on WebM format Brief history of WebP... ● Initial release (2010) ○ Lossy compression for true-color graphics ● October, 2011 ○ Color profile support ○ XMP metadata ● August, 2012 ○ Lossless compression support ○ Transparency (alpha channel) support Now a viable alternative and replacement to JPEG, PNG ● WIP + future... ○ Animation + metadata ○ Encoding performance ○ Better support for ARM and mobile ○ Layer support (3D images) + high color depth images (> 8 bits) WebP vs. -

Life Without Flash

Life without Flash Are your courses ready? After December 31, 2020, browsers will no longer support the Flash Player. Here is Adobe’s announcement: https://theblog.adobe.com/adobe-flash-update/ What does this mean for HSC Moodle course owners? Most LMS systems and browsers are transitioning away from Flash. You may be at risk of losing your online courses or resources, if they are Adobe Flash only. Moodle courses will need to be republished to alternate formats such as HTML5, MP4, etc. as well as halting any new flash based programs from being uploaded before the December 31st deadline. Many programs have already been getting ready for this change and already offer a conversion to another format. Check with your software support/IT to see how to make this transition easier. How do I find out if my course uses Flash? If you suspect a resource uses Flash, you can simply right-click what you believe to be Flash content to see if a Flash context menu appears: If you are using a browser that blocks Flash content, you may see icons like these: What is the alternative? An alternative solution for course owners is HTML5. HTML5 works with the same multimedia elements as Flash and many web developers have already begun moving to HTML5, which means it‘s supported by most browsers and you won’t need to install anything extra. HTML5-based courses will continue to function as expected. What should I do if my course uses Flash? If Flash courses are published using Flash/HTML5, and designed to fall back to HTML5 when the Flash plugin is removed from the browser, test your courses fall back capability to see whether HTML5 will work as expected. -

Sovereign Wealth Funds 2019 Managing Continuity, Embracing Change

SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS 2019 MANAGING CONTINUITY, EMBRACING CHANGE SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS 2019 Editor: Javier Capapé, PhD Director, Sovereign Wealth Research, IE Center for the Governance of Change Adjunct Professor, IE University 6 SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS 2019. PREFACE Index 11 Executive Summary. Sovereign Wealth Funds 2019 23 Managing Continuity...Embracing Change: Sovereign Wealth Fund Direct Investments in 2018-2019 37 Technology, Venture Capital and SWFs: The Role of the Government Forging Innovation and Change 55 SWFs in a Bad Year: Challenges, Reporting, and Responses to a Low Return Environment 65 The Sustainable Development Goals and the Market for Sustainable Sovereign Investments 83 SWFs In-Depth. Mubadala: The 360-degree Sovereign Wealth Fund 97 Annex 1. Sovereign Wealth Research Ranking 2019 103 Annex 2. Sovereign Wealth Funds in Spain PREFACE 8 SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS 2019. PREFACE Preface In 2019, the growth of the world economy slowed by very little margin for stimulating the economy to 2.9%, the lowest annual rate recorded since the through the fiscal and monetary policy strategies. subprime crisis. This was a year in which the ele- In any case, the developed world is undergoing its ments of uncertainty that had previously threate- tenth consecutive year of expansion, and the risks ned the stability of the cycle began to have a more of relapsing into a recessive cycle appear to have serious effect on economic expansion. Among these been allayed in view of the fact that, in spite of re- elements, there are essentially two – both of a poli- cord low interest rates, inflation and debt remain at tical nature – that stand out from the rest. -

Robust Graphics Metafile Compositing 1 of 57

Robust Graphics Metafile Compositing 1 of 57 Abstract A graphics metafile typically contains a series of graphic vector outline commands that allow a picture or design to be produced by executing those commands within the context of a graphics display. Unlike other graphics file formats such as bitmaps, metafiles are often more flexible in that they may be more easily scaled or manipulated since they are not tied to a discrete pixel resolution. Most often, a system will execute the specified vector commands scaled to a desired size within a raster-scan or pixel-based device context, where, for example, pixels that lie within vector outlines are set with specified color information. When a subset of vector commands overlap or otherwise intersect with previously drawn or executed commands, the pixels within the overlapped areas are simply reset to the color specified by the more recent vector commands. Thus, potential redundancies within a metafile (i.e. situations where multiple commands repeatedly “paint” within the same area) are resolved through this process of rasterization where more recent commands always take precedence over those that were previously executed. However, for many applications, the loss of flexibility that results from rasterization (e.g. loss of detailed outline information, etc.) makes it unsuitable for developing a more usable composite representation of a metafile’s vector commands. Specifically, it may be desirable to eliminate redundancies within vector outlines by actually modifying the underlying outlines directly such that painting within any given area never occurs more than once (i.e. no overlapping occurs). The resultant composite representation may be beneficial in many respects. -

Table 1. Visualization Software Features

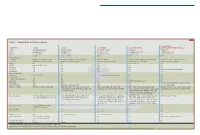

Table 1. Visualization Software Features INFORMATIX COMPANY ALIAS ALIAS AUTODESK AUTO•DES•SYS SOFTWARE INTERNATIONAL Product ALIAS IMAGESTUDIO STUDIOTOOLS 11 AUTODESK VIZ 2005 FORM.Z 4.5 PIRANESI 3 E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Use website form [email protected] [email protected] Web site www.alias.com www.alias.com www.autodesk.com www.formz.com www.informatix.co.uk Price $3,999 Starts at $7,500 $1,995 $1,495 $750 Operating systems Supported Windows XP/2000 Professional Windows XP/2000 Professional, SGI IRIX Windows 2000/XP Windows 98/NT/XP/ME/2000, Macintosh 9/X Windows 98 and later, Macintosh OS X Reviewed Windows XP Professional SP1 Windows XP Professional SP1 Windows XP Professional SP1 Windows XP Professional SP1 Windows XP Professional SP1 Modeling None Yes Yes Solid and Surface N/A NURBS Imports NURBS models Yes Yes Yes N/A Refraction Yes Yes Yes Yes N/A Reflection Yes Yes Yes Yes By painting with a generated texture Anti-aliasing Yes Yes Yes Yes N/A Rendering methods Radiosity Yes, Final Gather No Yes, and global illumination/caustics Yes N/A* Ray-tracing Yes Yes Yes Yes N/A* Shade/render (Gouraud) Yes Yes Yes Yes N/A* Animations No† Yes Yes Walkthrough, Quicktime VR N/A Panoramas Yes Yes Yes Yes Can paint cubic panorams and create .MOV files Base file formats AIS Alias StudioTools .wire format MAX FMZ EPX, EPP (panoramas) Import file formats StudioTools (.WIRE), IGES, Maya IGES, STEP, DXF, PTC Granite, CATIA V4/V5, 3DS, AI, XML, DEM, DWG, DXF, .FBX, 3DGF, 3DMF, 3DS, Art*lantis, BMP, DWG EPX, EPP§; Vedute: converts DXF, 3DS; for plans UGS, VDAFS, VDAIS, JAMA-IS, DES, OBJ, EPS IGES, LS, .STL, VWRL, Inventor (installed) DXF, EPS, FACT, HPGL, IGES, AI, JPEG, Light- and elevations; JPG, PNG, TIF, raster formats AI, Inventor, ASCII Scape, Lightwave, TIF, MetaFo;e. -

Exporting SWF Files.Pdf

Like what you see? Buy the book at the Focal Bookstore Flash + After Effects Chris Jackson ISBN 978-0-240-81031-7 Flash Video (FLV) contains only rasterized images, not vector art. FLV files can be output directly from the Render Queue in After Effects. Render settings allow you to specify size, compression, and other output options. The FLV file can then be imported into Flash and published in a SWF file, which can be played by the Flash Player. FLV files can be imported into Flash using ActionScript or Flash components. Components provide additional control of the visual interface that surrounds the imported video. You can also add graphic layers on top of the FLV file for composite effects. An alternative to saving a composition as a SWF and FLV file is to export it as an image sequence. After Effects renders each image file with a numerically sequential naming convention. Upon importing the first image, Flash recognizes the naming convention and prompts you to import the entire sequence (Figure 3.5). Image sequences should be imported into a movie clip or graphic symbol. This allows for more flexibility in your Flash project. Figure 3.5: After Effects can also export image sequences. It uses a sequential naming convention that Flash recognizes and allows you to import the entire sequence. Both applications include many tools that allow you to easily composite graphics and video. The previous chapter discussed how to save Flash content to After Effects. File size was not a concern since the final output was video. The exercises in this chapter focus on exporting After Effects content to Flash, with an emphasis on maintaining a respectable file size for Web delivery. -

Swf Download As Pdf SWF Player: How to Open SWF Files on Mac

swf download as pdf SWF Player: How to Open SWF Files on Mac. That's what asked most frequently on Quora by Mac users. Nowadays, it is very common to find SWF files online. You can find these in a variety of multimedia applications, like games or other apps. However, there are still several issues on how to open SWF files or play SWF on Mac, which can be easily used on the Windows system. Also, another problem is that many people are yet not aware of how to convert them by a 3-rd party on Mac. Read further to know certain sure-shot ways of opening and running these files that we have listed after thorough research and careful selection. Also, you can find ways on how to convert SWF files on Mac. Part 1. What is SWF Format. If you work a lot with graphics and media, then you must have heard about the SWF file format, which is short for Small Web Format (also called ShockWave file). It is basically an Adobe flash file format that contains different kinds of videos and vector type animations. Initially created by Macromedia, this format is now owned by Adobe, and the files are mostly used by people to deliver multimedia content across the web safely and securely. However, you can't open it on Mac without any help from a 3-rd professional program, which means that you need either an SWF player or convert SWF files to a different format. Part 2. How to Play SWF Files Online. -

Vector Graphics

CS404 Vector Graphics Particularly attractive for networked multimedia Compact Scalable Resolution independent Easy to edit However, without standards, adoption of vector graphics for the web has been delayed. Official SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics) De facto SWF (Flash file format) http://www.carto.net/papers/svg/comparison_flash_svg/ © 2004 Ray S. Babcock CS404 Coordinates In vector graphics, images are built up using shapes that can be easily described mathematically. Coordinates In general, real values on x-y axes y 3 (2.35, 2.9) 2 1 xx 1 2 3 © 2004 Ray S. Babcock CS404 Coordinate Transformations Often needed to change ªuser spaceº to ªdevice spaceº Y often increases downward on display device application programming interfaces (APIs) Scale is often different between internal scene coordinates and the display device. © 2004 Ray S. Babcock CS404 Vectors Pairs of coordinates can define displacements P2 P2 - P1 Y2 - Y1 P1 X2 - X1 When two points are used to specify a displacement in this way, we call it a two dimensional vector. It has length and direction but not specific position. © 2004 Ray S. Babcock CS404 Objects in Vector Graphics Points Straight Lines Circles Ellipses Squares Rectangles Etc. We can use coordinate geometry to derive equations for arbitrary sized objects. © 2004 Ray S. Babcock CS404 Storage We only need to store the constants used by the formulas. When we need to ªdrawº an object, we retrieve the constants, and using the formula define the pixels that make up the object. For straight lines algorithms like Bresenham©s allow you to calculate pixels using only integer arithmetic (faster). -

Steganographic Techniques for Hiding Data in SWF Files Mark-Anthony Fouche, Martin Olivier

Steganographic Techniques for Hiding Data in SWF Files Mark-Anthony Fouche, Martin Olivier To cite this version: Mark-Anthony Fouche, Martin Olivier. Steganographic Techniques for Hiding Data in SWF Files. 7th Digital Forensics (DF), Jan 2011, Orlando, FL, United States. pp.245-255, 10.1007/978-3-642- 24212-0_19. hal-01569544 HAL Id: hal-01569544 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01569544 Submitted on 27 Jul 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Chapter 19 STEGANOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUES FOR HIDING DATA IN SWF FILES Mark-Anthony Fouche and Martin Olivier Abstract Small Web Format (SWF) or Flash files are widely used on the Internet to provide Rich Internet Applications (RIAs). This makes SWF files an excellent candidate for disseminating hidden data. However, digital forensic investigators are unable to detect and extract the hidden data because limited information is available about the techniques used to hide data in SWF files. This paper investigates several data insertion techniques for hiding data in SWF files. The techniques include ap- pending data to an SWF file, adding an extra Metadata tag, creating a custom Definition tag, and replacing fill bits with hidden data.