The Turks of Prague.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prague & Munich

Prague & Munich combo weekend! A chance to enjoy two of the most beauful, historic and largest beer consuming places on the planet in one weekend! Prague - The golden city, incredible architecture and sights, Charles bridge, Prague castle (the largest in the world), the ancient Jewish quarter, Easter European prices, Starbucks and other western food chains, wild nightlife & Czech Beer (pints for $1). Surely one of the most intriguing cies in the world as well as one of the most excing in Europe, Prague is a trip not to be missed! Munich - The land of lederhosen, pretzels and beer – and Oktoberfest! This famous Bavarian city as all of the culture, history, museums and of course beer to make it one of the world’s greatest cies! Munich’s reputaon for being Europe’s most fun city is well-deserved, as no maRer what season or me of year, there’s always a reason for a celebraon! Country: Prague - Czech Republic (Czechia); Munich - Germany Language Prague - Czech; Munich - German Currency Prague - Czech Koruna; Munich - Euro Typical Cuisine Prague - Pork, beef, dumplings, potatoes, beer hot spiced wine, Absinthe, Czech Beer. Munich - wurst (sausage), Pretzels, krautsalat (sauerkrautsalad), kartoffelsalat (potato salad) schweinshaxe (roasted pork knuckle), schnitzel, hendl (roasted chicken), strudels, schnapps, beer. Old Town Square, Lennon Wall, Wenceslas Square, Jewish Quarter, Astronomical Clock, Charles Bridge, Prague Castle. Must see: Prague - Old Town Square, Lennon Wall, Wenceslas Square, Jewish Quarter, Astronomical Clock, Charles Bridge, Prague Castle.. Munich - Horauhaus, Glockenspiel, English gardens, Beer Gardens DEPARTURE TIMES DEPARTURE CITIES Thursday Florence Florence - 8:00 pm Rome Rome - 5:00 -5:30 pm Fly In - meet in Prague Sunday Return Florence - very late Sunday night Rome - very late Sunday night/ early Monday morning WWW.EUROADVENTURES.COM What’s included Full Package: Transportation Only Package: Fly In Package: - round trip transportaon - round trip transportaon - 2 nights accommodaon in Prague - 1 night accomm. -

Eastern Europe and Baltic Countries

English Version EASTERN EUROPE AND BALTIC COUNTRIES GRAND TOUR OF POLAND IMPERIAL CAPITALS GRAND TOUR OF THE BALTIC COUNTRIES GDANSK MALBORK TORUN BELARUS GRAND TOUR OF POLAND WARSAW POLAND GERMANY WROCLAW CZESTOCHOWA KRAKOW CZECH REPUBLIC WIELICZKA AUSCHWITZ UKRAINE SLOVAKIA Tour of 10 days / 9 nights AUSTRIA DAY 1 - WARSAW Arrival in Warsaw and visit of the Polish capital, entirely rebuilt after the Second World War. Dinner and accommodation.SUISSE DAY 2 - WARSAW Visit of the historic center of Warsaw: the Jewish Quarter, Lazienkowski Palace, the Royal route. In the afternoon, visit of the WarsawMILANO Uprising Museum, dedicated to the revolt of the city during World War II. Dinner and accommodation. FRANCE DAY 3 - WARSAW / MALBORKGENOA / GDANSK PORTO FINO Departure for the Baltic Sea. Stop for a visit of the Ethnographic Museum with its typical architecture. Continue withNICE a visit of the Fortress of Malbork listed at the UNESCO World Heritage Site. Then, CANNES departure for Gdansk. Dinner and accommodation.ITALIE DAY 4 - GDANSK / GDNIA / SOPOT / GDANSK City tour of Gdansk. Go through the Golden Gate, a beautiful street with Renaissance and Baroque facades, terraces and typical markets, the Court of Arthus, the Neptune Fountain and finally the Basilica Sainte Marie. Continue to the famous resort of Sopot with its elegant houses, also known as the Monte Carlo of the Baltic Sea. Dinner and accommodation. DAY 5 - GDANSK / TORUN / WROCLAW Departure for Torun, located on the banks of the Vistula and hometown of the astronomer Nicolas Copernicus. Guided tour of the historical center and visit the house of Copernicus. Departure to Wroclaw. -

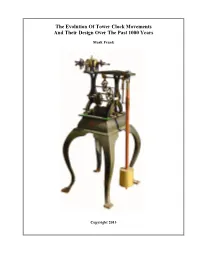

The Evolution of Tower Clock Movements and Their Design Over the Past 1000 Years

The Evolution Of Tower Clock Movements And Their Design Over The Past 1000 Years Mark Frank Copyright 2013 The Evolution Of Tower Clock Movements And Their Design Over The Past 1000 Years TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and General Overview Pre-History ............................................................................................... 1. 10th through 11th Centuries ........................................................................ 2. 12th through 15th Centuries ........................................................................ 4. 16th through 17th Centuries ........................................................................ 5. The catastrophic accident of Big Ben ........................................................ 6. 18th through 19th Centuries ........................................................................ 7. 20th Century .............................................................................................. 9. Tower Clock Frame Styles ................................................................................... 11. Doorframe and Field Gate ......................................................................... 11. Birdcage, End-To-End .............................................................................. 12. Birdcage, Side-By-Side ............................................................................. 12. Strap, Posted ............................................................................................ 13. Chair Frame ............................................................................................. -

Oktober 2017 – April 2018

Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Oktober 2017 – April 2018 Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Zuger Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch Kirsch FÜR AKTIVE, KREATIVE, GENIESSER UND ENTDECKER. BLEIBENDE GRUPPENERLEBNISSE. FOR THE ACTIVE, THE CONNOISSEURS, THE EXPLORERS AND THE CREATIVE. MEMORABLE GROUP EVENTS. zug-tourismus.ch T +41 41 723 68 00 [email protected] CityGuideZug 17. Auflage: Oktober 2017 - April 2018 INHALT ■ ZUG 6 ■ «SCHNAPSNASE» VON LUCA BARTULOVIC 18 ■ FÜHRUNGEN 28 ■ KULTUR | MUSEEN | GALERIEN 36 ■ FREIZEIT 50 ■ VERANSTALTUNGEN 54 ■ KINDER UND JUGENDLICHE 60 ■ AUSFLÜGE 62 ■ SHOPPING 72 ■ RESTAURANTS 80 ■ HOTELFÜHRER 86 ■ NACHTLEBEN 96 ■ INFORMATIONEN 100 ■ KARTEN 104 Ein Produkt von 4 ZUG HISTORISCHE SEHENSWÜRDIGKEITEN SEITE 10/11 ARCHITEKTUR SEITE 16/17 GESCHICHTE VON LUCA BARTULOVIC SEITE 18/27 KUNST IM ÖFFENTLICHEN RAUM SEITE 36/37 KUNSTHANDWERK & DESIGN SEITE 72/73 BESONDERE GESCHÄFTE SEITE 76/77 KULINARISCHE SPEZIALITÄTEN SEITE 78/79 NACHTLEBEN SEITE 96/97 IMPRESSUM Herausgeber / publisher: gt-image. GmbH, Godi Tresch, Kastanienweg 18, 4562 Biberist, Telefon +41 (0)79 762 62 09, www.gt-image.ch, [email protected] Grafische Arbeiten & Produktion / Graphic Design & Production: macfly | creative solutions, [email protected] | www.macfly.ch Gestaltung Titelblatt / layout title page: Elena Gabriel Druck / Printed by: Kalt Medien AG, Zug, www.kalt.ch Anzeigenpreise / Advertising Prices: Siehe Preisliste 2017 / Price list 2017 Auflage / Circulation: ca. -

Summer in Prague

Prague City Tourism Get to Know: We Love Water! Other Water Sports is here to help you! Summer is the ideal time to travel, and for those A multitude of sports, leisure, and cultural events take place at Information about Prague • maps and information brochures for the Žluté lázně complex in Podolí. There is a pool for kids and whose travels include a stop in Prague, there adults can swim in the Vltava. Here you can also rent traditional free • Prague Card • tickets for cultural and sport events • city are many ways to spice up the usual sightseeing tours • accommodation • public transportation tickets • souve‑ canoes, paddle boats and rowboats, water skis, and paddle‑ nirs from Prague • guide services Letná: Historical, with time on the water or other activities typical boards. Across the river on the Imperial Meadow (Císařské for this time of the year. Prague offers plenty louce) island at Waterman’s Paradise (Vodácký Ráj), you can Tourist information centres can be found in downtown of spots for open -air swimming and for water rent boats, rafts, and other boating equipment. If you’d like to Prague and at the international airport: sports, from canoeing, rafting, and kayaking, try water slalom, you’ll have to head a bit further upstream to Water! Love We Yet Hipster Troja – World and Czech Cup races in water slalom take place Letná know: to Get Old Town Hall as well as old -fashioned rowboats. There’s also in the specially designed canal there, and amateur enthusiasts Garden Sculpture Old Town Square 1, Prague 1 daily 9:00 a.m. -

Cities. Myswitzerland.Com Art, Architecture & Design in 26 Swiss Cities

Cities. MySwitzerland.com Art, architecture & design in 26 Swiss cities. Prolong the UEFA European Foot- ball ChampionshipTM 2008 with a holiday in Switzerland. MySwitzerland.com/euro08 Schaffhausen Basel Winterthur Baden Zürich St. Gallen-Lake Constance Aarau Solothurn Zug Biel/Bienne Vaduz La Chaux-de-Fonds Lucerne Neuchâtel Bern Chur Riggisberg Fribourg Thun Romont Lausanne Montreux-Vevey Brig Pollegio Sierre Sion Bellinzona Geneva Locarno Martigny Lugano Contents. Strategic Partners Art, architecture & design 6 La Chaux-de-Fonds 46 Style and the city 8 Lausanne 50 Culture à la carte 10 AlpTransit Infocentre 54 Hunting grounds 12 Locarno 56 Natural style 14 Lucerne 58 Switzerland Tourism P.O. Box Public transport 16 Lugano 62 CH-8027 Zürich Baden 22 Martigny 64 608, Fifth Avenue, Suite 202, Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau 23 Montreux-Vevey 66 New York, NY 10020 USA Basel 24 Neuchâtel 68 Switzerland Travel Centre Ltd Bellinzona 28 Schaffhausen 70 1st floor, 30 Bedford Street Bern 30 Sion-Sierre 72 London WC2E 9ED, UK Biel/Bienne 34 Solothurn 74 Abegg Foundation, Riggisberg 35 St. Gallen 76 It is our pleasure to help plan your holiday: Brig 36 Thun 80 UK 00800 100 200 30 (freephone) Chur 38 Vaduz 82 [email protected] USA 1 877 794 8037 Vitromusée, Romont 39 Winterthur 84 [email protected] Fribourg 40 Zug 88 Canada 1 800 794 7795 [email protected] Geneva 42 Zürich 90 Contents | 3 Welcome. Welcome to Switzerland, where holidaymakers and conference guests can not only enjoy natural beauty, but find themselves charmed by city breaks too. Much here has barely changed for genera- tions – the historic houses, the romantic alleyways, the way people simply love life. -

Ylholidaysswitzerland

Albert Einstein on a bench with YL HOLIDAYS SWITZERLAND beautiful Bern behind him TIMEISRELATIVEINBERN Wibke Carter travels to Switzerland and discovers a new world full of garlic, onions, high cuisine... and confetti have no chance. I am sur- onions in the foreground of illumi- Switzerland’s federal capital, in its rounded by children heavily nated historical buildings like the best light: a beautiful old town (a armed with … confetti. And as I town hall is an enchanting sight. Unesco World Heritage Site), sur- learn in the next split second, Other vendors offer seasonal vegeta- rounded by majestic alpine scenery they have no hesitation to use it bles, bread, hot mulled wine (a first and a friendly population which is Iwith full force. Before I can for me, alcohol this early) and souve- proud of its roots and traditions. even open my mouth in protest, nirs. No one seems bothered by the Historical research indicates that tiny shreds of coloured paper rain early hour or the winter coldness. the Zibelemarit originated in the down on me, but when I see the mis- “The Onion Market attracts more 1850s when farmers’ wives, the so- chievous sparkle in their eyes, I can- visitors than any other traditional called marmettes, came to Bern not help but smile. event in the canton,” says city guide around St Martin’s Day to sell their I had arrived in Switzerland the Margarete Schaller. “It’s a public produce, however a local legend day before for the Bern Zibelemarit holiday in Bern and everyone gets holds that the onion market is much or Onion Market, a traditional folk behind it.” older. -

Welcome to Southwest Germany

WELCOME TO SOUTHWEST GERMANY THE BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG VACATION GUIDE WELCOME p. 2–3 WELCOME TO SOUTHWEST GERMANY In the heart of Europe, SouthWest Germany Frankfurt Main FRA (Baden-Württemberg in German) is a cultural crossroads, c. 55 km / 34 miles bordered by France, Switzerland and Austria. But what makes SouthWest Germany so special? Mannheim 81 The weather: Perfect for hiking and biking, NORTHERN BADENWÜRTTEMBERGJagst Heidelberg from the Black Forest to Lake Constance. 5 Neckar Kocher Romantic: Some of Europe’s most romantic cities, 6 Andreas Braun Heilbronn Managing Director such as Heidelberg and Stuttgart. Karlsruhe State Tourist Board Baden-Württemberg Castles: From mighty fortresses to fairy tale palaces. 7 Pforzheim Christmas markets: Some of Europe’s most authentic. Ludwigsburg STUTTGART Karlsruhe REGION Baden-Baden Stuttgart Wine and food: Vineyards, wine festivals, QKA Baden-Baden Michelin-starred restaurants. FRANCE STR Rhine Murg Giengen Cars and more cars: The Mercedes-Benz 8 an der Brenz Outletcity and Porsche museums in Stuttgart, Ki n zig Neckar Metzingen Ulm Munich the Auto & Technik Museum in Sinsheim. MUC SWABIAN MOUNTAINS c. 156 km / 97 miles 5 81 Hohenzollern Castle Value for money: Hotels, taverns and restaurants are BLACK FOREST Hechingen Danube Europa-Park BAVARIA7 well-priced; inexpensive and efficient public transport. Rust Real souvenirs: See cuddly Steiff Teddy Bears Danube and cuckoo clocks made in SouthWest Germany. Freiburg LAKE CONSTANCE REGION Spas: Perfect for recharging the batteries – naturally! Black Forest Titisee-Neustadt Titisee Highlands Feldberg 96 1493 m Schluchsee 98 Schluchsee Shopping: From stylish city boutiques to outlet shopping. Ravensburg Mainau Island People: Warm, friendly, and English-speaking. -

Cross-Temporal Sonatas in Staccato Ostinato by Cenk Cokuslu, LP, Ncpsya

Cross-Temporal Sonatas in Staccato Ostinato By Cenk Cokuslu, LP, NCPsyA “Cities were built to measure time, to remove time from nature. There’s an endless counting down, he said. When you strip away all the surfaces, when you see into it, what’s left is terror.” ~ Don DeLillo, Point Omega “O reader, do not ask of me how I grew faint and frozen then – I cannot write it: all words would fall far short of what it was. I did not die, and I was not alive; think for yourself, if you have any wit, what I became, deprived of life and death. The emperor of the despondent kingdom so towered from the ice, up from midchest, that I match better with a giant’s breadth than giants match the measure of his arms…” ~ Dante Alighieri (Inferno XXXIV, 22-31) The sleeping patient is panicked; because he cannot have a nightmare; he cannot wake up or go to sleep; he has mental indigestion ever since.” ~ Wilfred R. Bion, Learning from Experience This is a tale of Future Anterior in Future Anterior. Future Anterior is a tense created to deal with the paradox of the a-temporality. A tense allowing to live and to pretend to be living as well as to have biologically lived while simultaneously maintaining the feeling of being dead inside. An invented predicate with the aim to deal simultaneously with the reality but also the impossibility of Thanatos. In other words, not only to listen to the sonatas, but also to become a participant and a spectator of a bleak psychic oratorio. -

L'horloge Astronomique De Le Cathédrale Notre Dame

Astrological, Political, Religious and Cultural History L’Horloge Astronomique de le Cathédrale Notre Dame Marcha Fox January 2011 www.ValkyrieAstrology.com [email protected] Copyright © 2011 All Rights Reserved by Marcha Fox 1 L’Horloge Astronomique de le Cathédrale Notre Dame: Astrological, Political, Religious and Cultural History by Marcha Fox Like many artifacts emanating from Christian worship in that age of religious preoccupation, the timepiece of the Middle Ages developed into a work of beauty and complexity. Clocks became showpieces. --Anthony Aveni1 Introduction L’Horloge Astronomique, the Astronomical Clock, housed in the Cathédrale Notre-Dame in Strasbourg, France is a living icon to a half-millennium of history. Its most striking feature is a massive planetary dial with the signs of the Zodiac and real- time representations of the locations of the Sun, Moon and five visible planets which, given today’s Christian attitude toward astrology, appears either hypocritical or a blatant dichotomy. Why would a Catholic cathedral display such a device if its purpose was not astrological? How and why did that attitude change over six hundred years? What was the real story behind L’Horloge Astronomique? The answer lies in the mosaical picture presented by the religious, scientific and political context between the 12th – 19th Centuries. Strasbourg, located in northeastern France, has a long and colorful history. Known in Roman times as Argentoratum where Julian defeated Chnodomar’s Germans in 357 CE, it was later named Strazzeburc -

Old Town Hall in Prague

BIG BIG In the footsteps of famous Many interesting and famous people have visited the Old Town Hall before you. Among them were such notable figures Old Town as Lech Walesa, Polish politician and dissident, later President of Poland; heir to the British Crown Prince Charles and Princess Diana; the famous French actress Annie Girardot; American actor Tom Cruise; Italian tenor Andrea Bocelli, and many others. Hall in Prague We look forward to your visit! The Old Town Hall is open daily: Mon 11.00 – 18.00 Tue – Sun 9.00 – 18.00 The Town Hall Tower is open daily: Mon 11.00 – 22.00 Tue – Sun 9.00 – 22.00 Night Tours: Fri, Sat from 20.30 Special tours for children: Sun from 14.00 Astronomical Clock: daily 9.00 – 23.00 Text and photo © Prague City Tourism 2013 www.prague.eu BIG BIG BIG BIG Old Town Hall in Prague Old Town Hall – the symbol of city authority – is probably the most beautiful sight in Prague's historic centre. Its origins date back to the 14th century, when townhouses were gradually merged into one building, and it has often figured prominently in the history of Prague and the Czech state. View from the tower Apostles from the chapel George of Poděbrady was elected king of Bohemia here, and Jan Želivský, a radical Hussite leader, was executed in its Medieval underground Astronomical Clock courtyard. Later, after the Battle of White Mountain, participants Medieval Prague reveals itself to you through the doors Prague's Astronomical Clock, which displays the motion in the Estates Uprising were taken directly to the gallows from in the basement of the Old Town Hall. -

Moses Cotsworth Fonds (RBSC-ARC-1140)

University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections Finding Aid - Moses Cotsworth fonds (RBSC-ARC-1140) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: April 23, 2020 Language of description: English University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections Irving K. Barber Learning Centre 1961 East Mall Vancouver British Columbia V6T 1Z1 Telephone: 604-822-2521 Fax: 604-822-9587 Email: [email protected] http://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/ http://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca//index.php/moses-cotsworth-fonds Moses Cotsworth fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Series descriptions