Ethnic Phenomena in Late Antiquity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journeys to Byzantium? Roman Senators Between Rome and Constantinople

Journeys to Byzantium? Roman Senators Between Rome and Constantinople Master’s Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Anthony Carrozzo, B.A Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Kristina Sessa, Advisor Timothy Gregory Anthony Kaldellis Copyright by Michael Anthony Carrozzo 2010 Abstract For over a thousand years, the members of the Roman senatorial aristocracy played a pivotal role in the political and social life of the Roman state. Despite being eclipsed by the power of the emperors in the first century BC, the men who made up this order continued to act as the keepers of Roman civilization for the next four hundred years, maintaining their traditions even beyond the disappearance of an emperor in the West. Despite their longevity, the members of the senatorial aristocracy faced an existential crisis following the Ostrogothic conquest of the Italian peninsula, when the forces of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I invaded their homeland to contest its ownership. Considering the role they played in the later Roman Empire, the disappearance of the Roman senatorial aristocracy following this conflict is a seminal event in the history of Italy and Western Europe, as well as Late Antiquity. Two explanations have been offered to explain the subsequent disappearance of the Roman senatorial aristocracy. The first involves a series of migrations, beginning before the Gothic War, from Italy to Constantinople, in which members of this body abandoned their homes and settled in the eastern capital. -

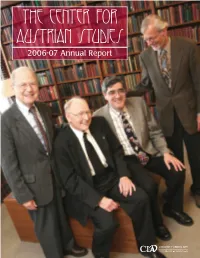

CAS Turns 30 —Let the Celebration Begin!

CENTER FOR AUSTRIAN STUDIES Vol. 19, No. 1 • Spring 2007 ASNAUSTRIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER CAS turns 30 —let the celebration begin! Plus: Don’t know much about Liechtenstein? Ambassador Claudia Fritsche does! Alison Fleig Frank’s “madcap” history of Left to right: William E. Wright, the Galician oil boom—and bust David F. Good, Gary B. Cohen, Gerhard H. Weiss ASN/TOC Letter from the Director 3 2006 Minnesota Calendar 3 News from the Center 4 ASN Interview: Herwig Wolfram 6 CAS Student Group News 8 Opportunities for Giving 9 ASN Interview: Claudia Fritsche 10 Publications: News and Reviews 14 Hot off the Presses 18 News from the Field 19 SAHH News 20 News from the North 21 ASN Interview: Charles Gati 22 Dispatch from CenterAustria 24 Salzburg 2006 Preview 25 Above, left to right, Gary Cohen, Jane Johnston, and Barbara Krausss-Christensen. Announcements 26 Below, left to right, Janna Fiesselmann, Tai Jin Kim, and Malte Franz. ASN Austrian Studies Newsletter Volume 19, No. 1 • Spring 2007 Editor: Daniel Pinkerton Editorial Assistants: Linda Andrean, Anne Carter, Barbara Reiterer ASN is published twice annually, in February and Septem- ber, and is distributed free of charge to interested sub- scribers as a public service of the Center for Austrian Studies. Editor’s Note Director: Gary B. Cohen Getting scholars together for a photo session is like herding cats. Whether current Administrative manager: Linda Andrean faculty members or emeriti, they lead extremely active lives, and coordinating their Editor: Daniel Pinkerton schedules (plus that of photographer Everett Ayoubzadah) isn’t easy. The result, however, was over fifty lively pictures that commemorate the history of the Center Send subscription requests or contributions for for Austrian Studies in a special way. -

Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation

Empire of Hope and Tragedy: Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Swain Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Timothy Gregory, Co-advisor Anthony Kaldellis Kristina Sessa, Co-advisor Copyright by Brian Swain 2014 Abstract This dissertation explores the intersection of political and ethnic conflict during the emperor Justinian’s wars of reconquest through the figure and texts of Jordanes, the earliest barbarian voice to survive antiquity. Jordanes was ethnically Gothic - and yet he also claimed a Roman identity. Writing from Constantinople in 551, he penned two Latin histories on the Gothic and Roman pasts respectively. Crucially, Jordanes wrote while Goths and Romans clashed in the imperial war to reclaim the Italian homeland that had been under Gothic rule since 493. That a Roman Goth wrote about Goths while Rome was at war with Goths is significant and has no analogue in the ancient record. I argue that it was precisely this conflict which prompted Jordanes’ historical inquiry. Jordanes, though, has long been considered a mere copyist, and seldom treated as an historian with ideas of his own. And the few scholars who have treated Jordanes as an original author have dampened the significance of his Gothicness by arguing that barbarian ethnicities were evanescent and subsumed by the gravity of a Roman political identity. They hold that Jordanes was simply a Roman who can tell us only about Roman things, and supported the Roman emperor in his war against the Goths. -

Visigoths and Romans: Integration and Ethnicity

Neal 1 Jennifer Neal May 9, 2011 Final Thesis Visigoths and Romans: Integration and Ethnicity Outside of Inginius’ fine home in Narbo, the January weather was far from pleasant. Inside the main apartments of the house, a woman and man sat beside each other enacting a Christian marriage ceremony. Emblems lay heavy against the woman’s body, indicating her imperial rank. Poised and proper as ever, she glanced again at the man who sat beside her wearing the garb of a Roman general and looking pleased. The audience gazed at her, exclaiming quietly at her beauty and the simple gown that draped from her shoulders. She smiled and turned her attention to the youths standing before her. Fifty young men, all dressed in different colors of silk, held platters that overflowed with gold and jewels so precious they nearly took her breath away. The irony almost drew a laugh from her lips. All of the wealth on those platters might be gifts meant to impress her, but they had been stolen from the coffers of her fellow Roman nobles during the Sack of Rome.1 That woman was Galla Placidia. The year was 414 and Galla Placidia, Roman princess and half-sister of Honorius, emperor of the Western Empire, sat next to Athaulf, barbarian king of the Visigoths.2 Willing as she was to marry Athaulf, there was no disguising the fact that he and his army of barbarians had pillaged her home and the surrounding areas to gain the treasure he now presented to her. Yet for all his Roman trappings, Athaulf was no Roman. -

Athanaric the Visigoth: Monarchy Or J

earlier one, any more than we can accept the pos- sibiliQ of arrioing at the name Jor the Gothic Athanaric the judge from Celtic, in a way in which tl~is possible for rciks. ,Such an obseruation, otherwise trivial in itsel_r, .rerues to characteriie the methodr Visigoth: arid Limits of the Blnctional compariso~~.This yields historical insighls which appb to the in- dividual case in question: along with new con- monarchy or sideratio~uconcerning rcx-rciks, an ar~qument i.s de~eloped againrt tlie opinion tliat Atizanaric's ,judgeship was olle of a lower rank than genuine J'udgeship. kingship, before which tiie GotIiZC clii@-for whateuer reasoz -- was supposed io haue draron back infear. This makes his judgeship look more A study in like an 'i~utitutionalized magisiracy', exercising rgal power for a set term, than a mere ethnic dignip. Further, the compariron estab1khe.r that the comparative Celtic, as well as tlie Gothic, judqechip was pouibly held in dual,fashio~z,or could be held tltat history wq, bcfore the period under o6,seruaiion; howeuer, the pairs to be dealt with here do 1101 represent afly 'Dioscurian' doi~blechiefdom but rather pairs of Herwig Wolfram chieftains riualling each olher. The archaic ex- perience may serue i~ithis instarice o~ilyas a model fol- siiaping lhe traditio~i. Finally, it is recognized - and thir co111d well be our most importa~~tfinding- that the judgeship is limiled, not onb in time but also in territoly: il 7he declcion to risk an attempt atfunctional com- had valid ,jurisdictiot~ o~zbi~zside the tribal ler- parison between two historicaljgures ouer a period ritoiy ilself. -

From Roman Provinces to Medieval Kingdoms / Ed

List of maps viii List of figures ix Contributors x Series editor's preface ' xiv Acknowledgments xvii Maps xix A. chronology of Romans and barbarians in Late Antiquity xxiii Introduction: Romans, barbarians, and the transformation of the Roman Empire 1 THOMAS F, X. NOBLE PART I Barbarian ethnicity and identity 29 1 The crisis of European identity 33 PATRICK J. GEARY 2 Gothic history as historical ethnography 43 HERWIG WOLFRAM 3 Origo et religio: ethnic traditions and literature in early medieval texts 70 HERWIG WOLFRAM 4 Does the distant past impinge on the invasion age Germans? 91 WALTER GOFFART CONTENTS 5 Defining the Franks: Prankish origins in early medieval historiography 110 IAN WOOD 6 Telling the difference: signs of ethnic identity 120 WALTER POHL 7 Gender and ethnicity in the early middle ages 168 WALTER POHL 8 Grave goods and the ritual expression of identity 189 BONNIE EFFROS Part II: Accommodating the Barbarians 233 9 The barbarians in late antiquity and how they were accommodated in the West 235 WALTER GOFFART 10 Archaeologists and migrations: a problem of attitude? 262 HEINRICH HARKE 11 Movers and shakers: the barbarians and the fall of Rome 277 GUY HALSALL 12 Foedet-a and foederati of the fourth century 292 PETER J. HEATHER 13 Cities, taxes, and the accommodation of the barbarians 309 WOLF LIEBESCHUTZ Part III: Barbarians and Romans in Merovingian Gaul 325 14 The two faces of King Childeric: history, archaeology, historiography 327 STEPHANE LEBECQ 15 Frankish victory celebrations 345 MICHAEL McCORMICK CONTENTS 16 Administration, law, and culture in Merovingian Gaul 358 IAN WOOD 17 ''Pax et disciplina'i Roman public law and the Merovingian state 376 ALEXANDER CALLANDER MURRAY Index 389 PPN: 120045273 Titel: From Roman provinces to Medieval kingdoms / ed. -

Difference and Accommodation in Visigothic Gaul and Spain

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2010 Difference and Accommodation in Visigothic Gaul and Spain Craig H. Schamp San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Schamp, Craig H., "Difference and Accommodation in Visigothic Gaul and Spain" (2010). Master's Theses. 3789. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.26vu-jqpq https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3789 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIFFERENCE AND ACCOMMODATION IN VISIGOTHIC GAUL AND SPAIN A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Craig H. Schamp May 2010 © 2010 Craig H. Schamp ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled DIFFERENCE AND ACCOMMODATION IN VISIGOTHIC GAUL AND SPAIN by Craig H. Schamp APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2010 Dr. John W. Bernhardt Department of History Dr. Jonathan P. Roth Department of History Dr. Nancy P. Stork Department of English and Comparative Literature ABSTRACT DIFFERENCE AND ACCOMMODATION IN VISIGOTHIC GAUL AND SPAIN by Craig H. Schamp This thesis examines primary sources in fifth- and sixth-century Gaul and Spain and finds a surprising lack of concern for ethnicity. -

Who Were the Eruli?

© Scandia 2008 www.scandia.hist.lu.se ABvar Elkgird Who were the Eruli? I. The received view In practically all the standard handbooks covering the history of the Germanic tribes,' the Eruli, or Heruli2 are represented as originating somewhere in Scan- dinavia. Thus A. kippold in Der Kleine Pauly (1967) describes them as a Ger- manic tribe, expelled from Scandinavia by the Danes around A.D. 250. In all es- sentials Lippold agrees with B. Rappaport's long article in the unabridged Pau- lys Real-Encyklopadie, 2nd ed. 1913. The same general picture emerges from the shorter and much less specific ar- ticle by R. Much in Hoops' Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, 2nd ed. 1913. The Eruli are said to have had their original home ("Stamrnsitz") in Scandinavia. Following the sixth-century historian Jordanes, Much declares that the EruIi were driven out by the Danes. After this, part of the tribe settled somewhere in northwest Germany, from where they made an abortive incursion into Gau'l in 287. Another part of the tribe, says Much, accompanied the Goths to the region north of the Black Sea. Much also refers to a very detailed story by the sixth century Greek historian Prokopios, in which a group of Eruli, led by members of their royal family, made a long trek from 1llyricu.m to Scandinavia some time in the beginning of the sixth century. This is described by Much as a "return" ("Riickwanderung") of the tribe to their ancestral home. One of the standard works on the history of the ancient Germanic tribes, by Ludwig Schmidt, has the same story and the same interpretation, both in the first edition (1910) and in the second (1933). -

A Comparative Perspective from the Early Medieval West

chapter 10 Genealogy: A Comparative Perspective from the Early Medieval West Walter Pohl1 Genealogies and similar forms of structuring descent were widely diffused in recorded history; indeed, they offered one basic “perceptual grid” for shaping the past, legitimizing the present and preparing for the future.2 Yet they did not carry the same weight, or have the same meaning in different historical contexts. The present article addresses the question how much they mattered in early medi- eval continental Europe, where and when. It will briefly reassess the evidence from the mid-6th to the mid-9th century. Taken together, the following examples provide impressive traces of genealogical thinking; they could be (and often have been) taken as tips of an iceberg, and interpreted as written traces of detailed genealogical knowledge and its oral transmission among the “Germanic” elites of the post-Roman kingdoms. I will argue that we need to be more precise and also acknowledge the limits of genealogical thinking and of its social impact: perhaps there was no single iceberg? Among the elites, noble descent may have mattered, but it rarely needed to be specified, and it seems that actual genealogical knowl- edge seldom stretched back more than three or four generations.3 Royal succes- sion was usually represented by king lists rather than royal pedigrees. Strikingly, neither of these have been transmitted from the Merovingians’ more than 250 years of rule. Genealogies gradually become more prominent in our evidence from the Carolingian period; but it seems that the emerging Merovingian and Carolingian pedigrees were not based on pre-conceived oral genealogical knowl- edge ultimately written down, but were experimentally created and expanded on the basis of written documents in ecclesiastic institutions. -

The Center for Austrian Studies 2006-07 Annual Report the 2006-07 Staff Editor: Daniel Pinkerton, M.F.A

THE CENTER FOR AUSTRIAN StUDIES 2006-07 Annual Report the 2006-07 staff Editor: Daniel Pinkerton, M.F.A. in playwriting, M.A. in European history, has worked at the Center since 1990. He has edited the Austrian Studies Newsletter since January 1992 and the Annual Report since 1991. He also assists the director in special projects such as writing grants, website design, and preparing graphics for the Austrian History Yearbook. Student Staff: Anne Carter was a Ph.D. candidate in English, and successfully defended her dissertation in November 2006. She worked at the Center for the entire academic year as editorial assitant for the CAS book series and the Austrian Studies Newsletter. Barbara Reiterer, CAS/BMBWK Research Fellow, was funded by Austria’s Federal Ministry for Education, Science, and Culture. She is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the University Front row, left to right: Daniel Pinkerton, Linda Andrean, Barbara Reiterer, Nicole Phelps. of Graz and has been accepted into the Program Back row, left to right: Anne Carter, Gary B. Cohen, Annett Richter. (photo by Karl Krohn) in the History of Science and Technology at the University of Minnesota as a Ph.D. candidate Director: Administrative Manager: beginning in fall 2007. She coordinated the Gary B. Cohen, professor of history, University Linda Andrean, B.A. in Anthropology and lecture series and, with Linda Andrean, the of Minnesota. Education: B.A., University of History, B.S. in Secondary Education, came to Austrian student events. She was also an editorial Southern California, 1970; M.A., Princeton the Center in June 2004 after twenty years of assistant for the Austrian Studies Newsletter and University, 1972; Ph.D., Princeton University, service in the University of Minnesota Academic assisted the director on special projects. -

SŤAHOVANIE NÁRODOV (454 – 568) SŤAHOVANIE NÁRODOV Ostrogóti, Longobardi Gepidi, Aslovania (454 –568) Peter Bystrický 12/11/08 4:37:24 PM Peter Bystrický

SŤAHOVANIE NÁRODOV Mgr.M Peter Bystrický, PhD. (1976) je vedeckým (454 – 568) ppracovníkom Historického ústavu Slovenskej aka- ddémie vied v Bratislave. Venuje sa obdobiu nesko- Ostrogóti, Gepidi, Longobardi a Slovania rrej antiky a včasnostredovekým dejinám Slovenska ppred príchodom Slovanov. Monografi aSťahovanie národov (454 – 568) vychádza z jeho štúdií a článkov vo vedeckých a popu- lárno-vedeckých časopisoch. SŤAHOVANIE NÁRODOV (454 – 568) SŤAHOVANIE Peter Bystrický Peter Peter Bystrický obalka_final.indd 1 12/11/08 4:37:24 PM Peter Bystrický ∂ SŤAHOVANIE NÁRODOV (454 – 568) Ostrogóti, Gepidi, Longobardi a Slovania ∂ ISBN 978-80-970060-0-6 kniha.indd 1 12/11/08 8:03:13 PM SLOVENSKÁ AKADÉMIA VIED HISTORICKÝ ÚSTAV © Text: Mgr. Peter Bystrický, PhD. Monografi a Sťahovanie národov (454 – 568) je výsledkom grantu „Slovensko ako súčasť stredove- kého Uhorského kráľovstva“ na Historickom ústave SAV č. 2/6201/27. Jej vydanie fi nančne podporili: Ministerstvo kultúry SR, Literárny fond, SAVOL (Spoločnosť auto- rov vedeckej a odbornej literatúry), občianske združenie Spoločnosť PRO HISTORIA a Historický ústav SAV Recenzenti Ján Steinhübel, CSc. (Historický ústav SAV) Doc. PhDr. Pavol Valachovič, CSc. (Filozofi cká fakulta UK Bratislava) Zodpovedná redaktorka Mgr. Miroslava Čulenová Návrh obálky a grafi cká úprava Jozef Hupka Technický redaktor Jozef Hupka Obálka Huni, v čele s Attilom, pri vpáde do Itálie. Z obrazu V. Checu. Vydavateľ Občianske združenie Spoločnosť PRO HISTORIA Všetky práva vyhradené. Žiadnu časť tejto publikácie nemožno reprodukovať, kopírovať, uchovávať ani prenášať prostredníctvom nijakých médií – elektronických, mechanických, rozmnožovacích či iných – bez predchádzajúceho písomného súhlasu autora. Bratislava 2008 ISBN 978-80-970060-0-6 kniha.indd 2 12/11/08 8:03:13 PM Peter Bystrický ∂ SŤAHOVANIE NÁRODOV (454 – 568) Ostrogóti, Gepidi, Longobardi a Slovania ∂ Bratislava 2008 kniha.indd 3 12/11/08 8:03:13 PM PETER∂ BYSTRICKÝ OBSAH ÚVOD ……………………………………………………….............…………………………. -

How the Franks Became Frankish: the Power of Law Codes and the Creation of a People

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2020 How the Franks Became Frankish: The Power of Law Codes and the Creation of a People Bruce H. Crosby Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Crosby, Bruce H., "How the Franks Became Frankish: The Power of Law Codes and the Creation of a People" (2020). University Honors Program Theses. 531. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/531 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How the Franks Became Frankish: The Power of Law Codes and the Creation of a People An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in History By Bruce Crosby Under the mentorship of Dr. James Todesca ABSTRACT During the fifth century, many Germanic peoples in Roman service assumed control over vast swathes of the Western Empire. Among these peoples were the Franks, who lend their name to the modern European nation of France. Thus, a question arises regarding how this came to be: how did illiterate tribes from Germania create a culture of their own that supplanted the Romans? Through an analysis of Frankish legal texts like the Lex Salica and the Capitularies of Charlemagne, this paper argues that the Franks forged their own identity by first formalizing their Germanic customs in the early sixth century and then by imposing more sweeping laws in the eighth and ninth centuries that portrayed them as champions of Christianity.