Sennar Capital of Islamic Culture 2017 Project. Prelimi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 Highlights

Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 UNICEF and partners assess damage to communities in southern Khartoum. Sudan was significantly affected by heavy flooding this summer, destroying many homes and displacing families. @RESPECTMEDIA PlPl Reporting Period: July-September 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers • Flash floods in several states and heavy rains in upriver countries caused the White and Blue Nile rivers to overflow, damaging households and in- 5.39 million frastructure. Almost 850,000 people have been directly affected and children in need of could be multiplied ten-fold as water and mosquito borne diseases devel- humanitarian assistance op as flood waters recede. 9.3 million • All educational institutions have remained closed since March due to people in need COVID-19 and term realignments and are now due to open again on the 22 November. 1 million • Peace talks between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan Revolu- internally displaced children tionary Front concluded following an agreement in Juba signed on 3 Oc- tober. This has consolidated humanitarian access to the majority of the 1.8 million Jebel Mara region at the heart of Darfur. internally displaced people 379,355 South Sudanese child refugees 729,530 South Sudanese refugees (Sudan HNO 2020) UNICEF Appeal 2020 US $147.1 million Funding Status (in US$) Funds Fundi received, ng $60M gap, $70M Carry- forward, $17M *This table shows % progress towards key targets as well as % funding available for each sector. Funding available includes funds received in the current year and carry-over from the previous year. 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF’s 2020 Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) appeal for Sudan requires US$147.11 million to address the new and protracted needs of the afflicted population. -

SUDAN Situation Report Last Updated: 3 Oct 2019

SUDAN Situation Report Last updated: 3 Oct 2019 HIGHLIGHTS (3 Oct 2019) Humanitarian partners have developed a cholera readiness and response plan and are seeking US$ 20.3 million for the next three months. Number of suspected cholera cases continues to rise, with 226 cases—including eight deaths— reported in Blue Nile and Sennar states as of 30 September 2019. Federal Ministry of Health has requested Oral Summary of Sudan cholera response plan budget Cholera Vaccine (OCV) to target 1.6 million people in high risk areas of Blue Nile and Sennar states. Forecasts estimate up to 13,200 cholera cases in the next 6 months in high risk states of Sudan. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (2019) CONTACTS Paola Emerson 364,200 226 $1.1B $452.1M Head of Office People affected by Suspected cholera Required Received [email protected] floods cases j e r , Mary Keller d y n r r A Head, Monitoring and Reporting o 39% 17 2 S Progress [email protected] States affected by States with cholera floods (HAC & outbreak Partners) FTS: https://fts.unocha.org/appeal s/670/summary EMERGENCY RESPONSE (3 Oct 2019) Humanitarian Cholera Readiness and Response Plan The major disease outbreaks in Sudan for the past decades are grouped into three categories based on type of transmission: water-borne, vector-borne and vaccine-preventable diseases. This is mainly attributed to low access to and coverage of safe drinking water, and sanitation, environmental sanitation and low vaccination coverage; exacerbated by weak health and WASH infrastructures. The country experienced the worst flooding since 2015 creating favourable ground for emergence and aggravation of water-borne and vector-borne diseases such as cholera, dysentery, dengue fever, malaria, etc. -

The Sudan Flood Impact Rapid Assessment

The Sudan 2020 Flood impact rapid assessment September 2020 A joint assessment with the Government of the Sudan The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on the map(s) in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. Cover photo: ©FAO The Sudan 2020 Flood impact rapid assessment September 2020 A joint assessment with the Government of the Sudan Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2020 Assessment highlights • Torrential rains and floods combined with the historical overflow of the River Nile and its tributaries caused devastating damages to agriculture and livestock across the Sudan. In the rainfed agriculture sector, around 2 216 322 ha of the planted area was flooded, representing 26.8 percent of cultivated areas in the 15 assessed states. • The production loss due to the crop damage by floods is estimated at 1 044 942 tonnes in the rainfed areas. Sorghum – which is the main staple food in the country – constitutes about 50 percent of the damaged crops, followed by sesame at about 25 percent, then groundnut, millet and vegetables. • The extent of the damage to planted areas in the irrigated sector is estimated at 103 320 ha, which constitutes about 19.4 percent of the total cultivated area. The production loss is under estimation. -

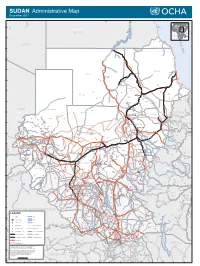

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus -

G Eneral L Ogistics P Lanning M Ap: June 2021

20°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 25°0'0"E 27°30'0"E 30°0'0"E 32°30'0"E 35°0'0"E 37°30'0"E 40°0'0"E 1 n 2 a EGYPT N " 0 d 0 ' 0 3 ° 2 u 2 2 S e HALA'IB n u J Wadi Halfa/Aswan : Wadi Halfa !( p LIBYA SAUDI ARABIA a Al Uwaynat M HALFA g n i JUBAYT ELMA'AADIN n n R a l E P D s c S i t Delgo ABU HAMAD E !( s DELGO N " i 0 A ' 0 ° g 0 AL BUHAIRA 2 o RED SEA L Kerma !( AL BURGAIG Port Sudan H! l Alborgaig Abu Hamad NORTHERN ! !( AL GANAB (!o a r e Dongola DONGOLA H! n Suakin !(h e ! SINKAT G ! Sin!kat Karima !( Marawi Goled! Gibli !( Tok! ar Haya MERWOE RIVER NILE HAYA !( ! Aqiq Ed Debba BARBAR !( Berber !( TAWKAR ATBARA AGIG AL GOLID Atbara!( Ed Damer N H! " Deru! deb AL MALHA DORDIEB 0 ' 0 3 ° 7 1 AD DAMAR AD DABBAH REIFI HAMASHKUREIB AL MATAMA El Matamma !( !(Shendi REIFI AD DELTA NORTH DARFUR UM BADA SHENDI REIFI TELKOK KARRARI BAHRI Aroma KHARTOUM KASSALA REIFI AROMA! Keren SHARG AN NEEL REIFI KHASHM ELGIRBA REIFI NAHR ATBARA ERITREA Massawa !. Akwirdet ! KHARTOUoM Mitsiwa Bahia Khartoum (! Sh!egeg Karo Kassala UM DURMAN H! Wakhaim HALFA AJ JADEEDAH CHAD Furawiya UM BARU ! GEBRAT AL SHEIKH Rayrah Asmera ! SOUDARI JEBEL AWLIA ! New Halfa Bamina !( (!o ! Muzbat REIFI GHARB KASSALA AT TINA ! KERNOI Karnoi! AL KAMLIN Ma!lha El Kamlin Dekemhare !( N Umm Baru AL BUTANAH " ! 0 Tina! ' SHARG AL JAZIRAH REIFI KASSLA 0 H ° !( ! 5 El Qutainah Adi Ugri 1 ! !( NORTH KORDOFAN AJ JAZIRAH Rufa'ah AL GITAINA AL HASAHISA !( ! !( An!ka Ana !Bagi El Hasahisa ! Baashim/tina ! Hamrat El Sheikh !( Jebrat El Sheikh UM ALGURA !Dankud !( UM RIMTA ! REIFI WAD ELHILAIW KULBUS KUTUM -

COVID-19 Situation Overview & Response

SUDAN COVID-19 Situation Overview & Response 11 October 2020 CONFIRMED CASES by state NO. OF ACTIVITIES by Organization as of 11 October 2020 13,691 International boundary IOM 912 State boundary UNHCR 234 Confirmed cases Undetermined boundary Save the children 193 Abyei PCA Area Red Sea ECDO 150 385 UNFPA 135 Number of confirmed cases RIVER RED SEA 836 6,764 NILE Plan International Sudan 39 Welthungerhilfe (WHH) 34 Deaths Recovered 391 438 WHO 23 NORTHERN HOPE 22 HIGHLIGHTS 146 NCA 20 9,841 The Federal Ministry of Health identified the first case of COVID-19 on 12 March WVI 19 OXFAM 12 2020. United Nations organisations and their partners created a Corona Virus 228 NADA Alazhar 12 Country Preparedness and Response Plan (CPRP) to support the Government. EMERGENCY NGO Sudan 12 NORTH DARFUR KHARTOUM On 14 March 2020, the Government approved measures to prevent the spread of KASSALA EMERGENCY 12 Khartoum the virus which included reducing congestion in workplaces, closing schools 1,137 TGH 11 By Organization Type: NORTH KORDOFAN and banning large public gatherings. From 8 July 2020, the Government started AL GEZIRA World Vision Sudan 11 GEDAREF NORWEGIAN 9 174 7 WEST REFUGEE COUNCIL to ease the lock-down in Khartoum State. The nationwide curfew was changed 203 (9.33%) (0.38%) DARFUR WHITE 274 Italian Agency 7 from 6:00 pm to 5:00 am and bridges in the capital were re-opened. Travelling Development Co. NGO Governmental 34 NILE 243 Near East Foundation 7 between Khartoum and other states is still not allowed and airports will 191 SENNAR CAFOD 6 CENTRAL WEST gradually open pending further instructions from the Civil Aviation Authority. -

Khartoum, Al Jazirah, Sennar and White Nile States Imagery Analysis: 02 - 06 September 2020 | Published 8 September 2020 | Version 1.0 FL20200826SDN

AÆ Floods ﺟﻣﮭ ورﯾﺔ اﻟﺳ ودان SUDAN Khartoum, Al Jazirah, Sennar and White Nile States Imagery analysis: 02 - 06 September 2020 | Published 8 September 2020 | Version 1.0 FL20200826SDN 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E E G Y P T N N " " 0 ' 0 ' 0 0 ° ° 7 7 1 1 «Å«Å )" ﻛﺑوﺷﯾﺔ D A Map location H Taragma C Khartoum )" ﺷﻧدي Asmara S U D A N ¥¦¬ ¥¦¬ )" Addis Ababa A ¥¦¬ S I O P U T H S U O D A N I H Juba T ¥¦¬ E River Nile N N " " 0 ' 0 ' 0 0 ° ° 6 6 1 أﺑو دﻟﯾﻖ 1 "( اﻟﺟزﯾ رة إﺳﻼﻧﺞ Satellite detected water extent, )" Kassala between the 02nd and the 06th September compared with the Khartoum أم د رﻣﺎن 28th August and the 1st اﻟﺧ رطوم "( September 2020 in Khartoum, Al ¥¦¬ اﻟﻛﻼﻛﻠﺔ اﻟﻘﺑﺔ Jazirah, Sennar and White Nile اﻟﻌﯾﻠﻔون "( States, Sudan )" ﻣدﯾﻧﺔ ﺟﯾﺎد اﻟ ﺻﻧﺎﻋﯾﺔ This map illustrates satellite-detected surface North Kordofan )" ﺟﺑل اوﻟﯾﺎء waters (cumulative) in Sudan as detected by )" VIIRS-NOAA satellite between 02 & 06 September 2020 compared with the 28th اﻟﻛﺎﻣﻠﯾن August and the 1st September 2020. Whtin )" N N " " 0 ' 0 ' 0 0 the analyzed area of about 900,000 km2, a ° ° 5 5 1 ﺗﻣﺑول 1 total of about 20,000 km2 of lands appear to )" be flooded. Based on Worldpop population رﻓﺎﻋﺔ data and the detected surface waters, about Al Hasahisa)" 1,700,000 people are potentially exposed or )" living close to flooded areas. The potentially exposed population is mainly located in the Al Jazirah states of Khartoum with ~600,000 people, Gedaref Sennar with ~250,000 people, Blue Nile with ود ﻣدﻧﻲ "(Al-Madina Arabاﻟﺷﺑﯾ راب اﻟﺧواﻟدة people and Al Jazirah with 170,000~ )" )" ~170,000 people. -

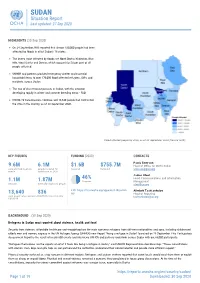

SUDAN Situation Report Last Updated: 27 Sep 2020

SUDAN Situation Report Last updated: 27 Sep 2020 HIGHLIGHTS (30 Sep 2020) On 24 September, HAC reported that almost 830,000 people had been affected by floods in all of Sudan’s 18 states. The states most affected by floods are North Darfur, Khartoum, Blue Nile, West Darfur and Sennar, which account for 54 per cent of all people affected. UNHCR and partners provided emergency shelter and essential household items to over 170,000 flood-affected refugees, IDPs and residents across Sudan The risk of desert locust persists in Sudan, with the situation developing rapidly in winter and summer breeding areas - FAO COVID-19 transmissions continue and 13,640 people had contracted the virus in the country, as of 28 September 2020. Flood-affected people by state, as of 22 September 2020 (Source: HAC) KEY FIGURES FUNDING (2020) CONTACTS Paola Emerson 9.6M 6.1M $1.6B $755.7M Head of Office for OCHA Sudan severely food-insecure people targeted for Required Received [email protected] people assistance in 2020 ! j James Steel e , r y r d 46% Head, Communications and Information r n o 1.1M 1.87M PA rogress Management refugees internally displaced people S [email protected] FTS: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/870/summ Alimbek Tashtankulov 13,640 836 ary Head of Reporting total people who contracted COVID-19-related deaths [email protected] COVID-19 BACKGROUND (30 Sep 2020) Refugees in Sudan most worried about violence, health and food Security from violence, affordable healthcare and enoughfood are the main concerns refugees from different nationalities and ages, including childrenand elderly men and women, express in the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) new Report “Being a refugee in Sudan” launched on 28 September. -

Among the Birds of the Eastern Sudan

THE AUK: A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY. Vo•.. xxxI. ArRIL, 1914. NO. 2 AMONG THE BIRDS OF THE EASTERN SUDAN. BY JOHN C. PHILLIPS. Plate XIII. • LOOKINGback on our short collectingtrip into the easternpart of the Sudan,the Blue-Nile basin,it is remarkablehow strongly the first few days of the trip stand out in memory. The novelty of groat spaces,of the groaning,toiling camels,of the burning noonsand deliciousnights, soondissolves into an everyday exis- tence, and one week becomesalmost exactly like the next; so exactly,in fact, that after a monthor moreone ceasesto remark on the weatherand almostforgets he is living out of doors. A feelingrather stealsover one that this is not the open air, but a groatglass house, steam heated and weatherproof. Beholdus then launchedsuddenly from the dusty train into the brilliant moonlightat Sennar. It was ChristmasEve, and all day long the train had been crawling away from Khartoum, over dustydurrah fields, at an averagerate of just twelvemiles an hour. Amidstgreat confusion we detrainedour ninecamels, giving three of them an opportunityto escape,which, camelllke, they soontook advantage of. In a large thorn enclosurewe stowedaway our luggage,made our beds and turned in. Supper was a brief affair that night. The full moonglared down upon us, a stripedhyena gave his very Female Caprimulgus eleanore• Phillips, three quarters natural size, 149 x x x ¸ 150 PniI.I.irs, Birds of the Sudan. [AAprU•l musicalcall, and from the sky abovecame the clamorof hundreds and it seemedthousands of EuropeanCranes. Off in the distance was the confusedsound of the village,donkeys, dogs and drumsall jumbledtogether and softenedinto a weird sort of chant. -

SUDAN Rural Livelihood Profiles for Eastern, Central, and Northern Sudan January 2015

SUDAN Rural Livelihood Profiles for Eastern, Central, and Northern Sudan January 2015 MAP OF LIVELIHOOD ZONES IN SUDAN FEWS NET Washington FEWS NET is a USAID-funded activity. The content of this report does not [email protected] necessarily reflect the view of the United States Agency for International www.fews.net Development or the United States government. i SUDAN Livelihood Profiles January 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Livelihood Zones in Sudan ................................................................................................................................................ i Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................................................... v Acronyms and Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................... v A Summary of the Household Economy Approach ...................................................................................................................... 1 The Household Economy Approach in Sudan .............................................................................................................................. 2 Overview of Rural livelihoods in Eastern, Central, and Northern Sudan ..................................................................................... 4 Northern Riverine Small‐scale Cultivation (Zone 1) .................................................................................................................... -

Quantifying and Evaluating the Impacts of Cooperation in Transboundary River Basins on the Water-Energy-Food Nexus: the Blue Nile Basin

Science of the Total Environment 630 (2018) 1309–1323 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Quantifying and evaluating the impacts of cooperation in transboundary river basins on the Water-Energy-Food nexus: The Blue Nile Basin Mohammed Basheer a,⁎, Kevin G. Wheeler b, Lars Ribbe a, Mohammad Majdalawi c, Gamal Abdo d, Edith A. Zagona e a Institute for Technology and Resources Management in the Tropics and Subtropics (ITT), Technische Hochschule Köln, Betzdorferstr. 2, 50679 Cologne, Germany b Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX13QY, United Kingdom c Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness Department, Faculty of Agriculture, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan d Water Research Center (WRC), University of Khartoum, Nile street, 11111 Khartoum, Sudan e Department of Civil, Environmental and Architectural Engineering, University of Colorado, 421 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309, USA HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • A daily model of the Blue Nile Basin is developed using RiverWare, HEC-HMS, and CropWat. • Satellite-based rainfall products are a valuable asset in modelling WEF nexus. • Changes in the economic gain from water, energy, and food are calculated for 120 scenarios. • The overall economic gain of the basin increases with raising the cooperation level. • Maximizing the overall economic gain requires transboundary management strategies. article info abstract Article history: Efficient utilization of the limited Water, Energy, and Food (WEF) resources in stressed transboundary river ba- Received 17 January 2018 sins requires understanding their interlinkages in different transboundary cooperation conditions. The Blue Nile Received in revised form 20 February 2018 Basin, a transboundary river basin between Ethiopia and Sudan, is used to illustrate the impacts of cooperation Accepted 20 February 2018 between riparian countries on the Water-Energy-Food nexus (WEF nexus). -

SUDAN RESPONSE DARFUR Last Updated: 09/30/18

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE SUDAN RESPONSE DARFUR Last Updated: 09/30/18 DARFUR-WIDE FAO GOAL IOM RI OCHA SC/US UNDP UNDSS UNHAS UNICEF NORTH WHO DARFUR WFP Kornoi Malha Tina Um Baru SUDAN-WIDE IOM FAO OCHA IMC Kulbus UNDP TGH Saya Kutum UNHAS War Child Canada Fata Borno Mallit UNICEF WRI Seleah El Sireaf Kafod WHO Korma Kuma WEST UNICEF Kabkabiya Ed Al Nagab El Fashir DARFUR Birkat Seira Umm Kaddada WFP Tawila Saraf Omra El Geneina ICRC Rockero UNHAS Abata Gildo Shangil Tobay Dar Al Salam UNHCR Masteri Golo Mornei Sullu Niertete Wada`ah Kango Haraza Zalingei Habila CENTRAL DARFUR Kass CHAD Garsila El Taweisha Foro Baranga Nyala Bendisi Mukjar SOUTH Abou Adid CRS Sarrow DARFUR FAO Mukjar IMC Locality Ed El Fursan Ed Daein NEF Adila Norwegian Church Aid Rehed Al Birdi SC/US Nyimeri EAST DARFUR TGH Buram VSF/G WRI ARC Am Dafok CARE Bahr el Arab CAR Locality UMCOR ARC PROGRAM KEY CARE USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM IMC Agriculture and Food Security Logistics and Relief Commodities Mercy Corps Economic Recovery and Market Multi-Sector Assistance World Vision Systems Nutrition Emergency Food Assistance Protection Food Vouchers INFORMA Rapid Response Fund SOUTH IC TI PH O A N Health R U G N O I Shelter and Settlements T SUDAN E Humanitarian Coordination G Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene U and Information Management S A A D I F D O Humanitarian Air Operations / D C H A / ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE SUDAN RESPONSE THE TWO AREAS, ABYEI, AND WEST KORDOFAN Last Updated: 09/30/18 SUDAN-WIDE PROGRAM KEY IOM USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM OCHA Agriculture