Planning for Agriculture in Wisconsin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chippewa County Farmland Preservation Plan

Chippewa County Farmland Preservation Plan October, 2015 Prepared by: Chippewa County Department of Planning & Zoning Chippewa County Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................3 Working Lands Initiative ....................................................................................................................................4 Agricultural Enterprise Areas – (AEA) ..............................................................................................................4 Other Plans .................................................................................................................................................................4 Chippewa County Comprehensive Plan – July 2010 ..........................................................................................4 Chippewa County Land & Water Resource Plan ...............................................................................................5 Land Use Conditions and Trends ...............................................................................................................................5 Land Use .............................................................................................................................................................5 Population ...........................................................................................................................................................6 -

Kenosha County Intensive Survey Report

Intensive Survey of Rural Kenosha County Including the towns of Somers, Paris, Brighton, Wheatland, and Randall By Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 For Wisconsin Historical Society State Historic Preservation Office 816 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 2019 Acknowledgments The following persons or organizations assisted in completing this project: Legacy Architecture, Inc. Jennifer L. Lehrke, Principal Historic Preservation Consultant Kenosha County Historical Society & Rowan Davidson, Historic Preservation Consultant Kenosha History Center Robert Short, Historic Preservation Consultant Jonathan Martens, Exhibition & Collections Gail Biederwolf, Administrative Services Coordinator Specialist Wisconsin Historical Society Others State Historic Preservation Office Kathy Emery Daina Penkiunas, State Historic Preservation Officer Jackie Klapproth Peggy Veregin, National Register Coordinator Chris Kraidich Joseph R. DeRose, Survey & Registration Historian Rachel Muhlenbeck Amy Wyatt, Historic Preservation Specialist Callie Rucker Charles Soper Kenosha County Robin Therese Tom Beaudry, Information Technology Deborah Vos Andy Buehler, Director, Department of Planning & Development Ben Fiebelkorn, Senior Land Use Planner Patricia Pendleton, GIS Coordinator Scott Schutze, Director, County Land Information Office Cheryl Schroeder, Office of the Register of Deeds The activity that is the subject of this intensive survey report has been financed entirely with the Wisconsin State Historic Preservation -

Fred L. Holmes a £

1948-CENTENNIAL EDITION-1948 M1 'A V, FRED L. HOLMES A £ OLD WORLD WISCONSIN AROUND EUROPE IN THE BADGER STATE Other Books by FRED L. HOLMES “Abraham Lincoln Traveled This Way” “George Washington Traveled This Way” “Alluring Wisconsin” “Badgei Saints and Sinners” “The Voice of Trappist Silence” •• OLD WORLD WISCONSIN Around Europe Jn the Badger State BY FRED L. HOLMES ILLUSTRATED WITH PHOTOGRAPHS, AND SKETCHES BY MAX FERNEKES “We are what we are because we stand on the shoulders of those who have preceded us. May we so live that those who follow us may stand on our shoulders.” —Anon. COPYRICHT, 1944 FRED L. HOLMES All rights reserved including the right to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form whatever. First printing, May, 1944 Second printing, September, 1944 TO LOUIS W. BRIDGMAN A CLASSMATE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN ALWAYS MY FRIEND WHOSE MANY SERVICES HAVE BEEN MOST HELPFUL 6 0 ea>. "7? »«•*• "ASIANS r_/?REN xmicm CM (l I swedes finns / . •toil ■*|HIK«TDH IMAMS /4»amti*wa« Russians 0 ICELANDERS A. V • 'MMIIC MiaoiT M«M vj T. SWEDES (ltC**U *Kll y • cuifo* f imiuu #«lM«i. OTjfx^xxt BELGIANS Russians FRENCH if* ••out "t • »IU»*9 ^ . udi*>H OANES ' 1 «IIUI«IUI BOHEMIANS 1 HOLLANDERS j HOLLANDERS GERMANS MAOIIOM • CORNISH « -T MOnt( OANES ) YANKEELAND V _ SERBIANS / MAP Of WISCONSIN SHOWING RACIAL GROUPS AND PRINCIPAL LOCALITIES WHERE THEIR SETTLEMENTS ARE LOCATED PREFACE Through many questionings and wanderings in my native state, I have formed an appreciation, beyond ordi¬ nary measure, of the people who are Wisconsin. -

FPP.06.10.2014.Draft

Adopted on XXX X, 2014 Eau Claire Board of Supervisors Resolution #X (2014) Prepared by: Eau Claire County Department of Planning and Development West Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission Financial Assistance Provided by: Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Planning & Development Committee Gordon Steinhauer, Chair Gary Gibson, Vice Chair James Dunning Ray Henning Steve Chilson Farmland Preservation Steering Committee Barry Kostka Bob Paddock Watford Seguin, Jr. Noel Kroeplin Kristina Beuning Dan Lindeman Mike Weiss Jane Mueller Phillip Chute Dudley (Joe) Smith Pat Shaffer Dean Zimmerman Mary Price Duane Merritt Larry Zimmerman EAU CLAIRE COUNTY 18 56 Eau Claire County FARMLAND PRESERVATION PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................1 WHAT IS FARMLAND PRESERVATION?.................................................................2 WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THE PROGRAM? ........................................................2 WHY IS IT IMPORTANT? ......................................................................................3 HISTORY OF THE FARMLAND PRESERVATION PROGRAM .............................................3 WISCONSIN WORKING LANDS INITIATIVE (WLI) ..........................................................5 PLANNING PROCESS ................................................................................................6 NATURAL RESOURCES .............................................................................................8 -

Organic Agriculture in Wisconsin by the Numbers

2012 STATUS REPORT ORGANIC AGRICULTURE IN WISCONSIN BY THE NUMBERS Wisconsin has experienced dramatic growth in organic agriculture since the National Organic Program was enacted in 2002. The number of organic farms in Wisconsin grew 157 percent from 2002 to 2007.1 Wisconsin's growth in organic farming mirrors global and national growth in this sector. Organic production in the U.S. is a small but rapidly growing part of worldwide organic production. Globally, 87 million acres were farmed under organic management in 2008, representing almost 1.4 million producers in 154 countries. This represents a nine percent increase in the acreage in organic production over 2007.2 U.S. certified organic acreage reached more than 4.1 million acres and 14,540 producers in 2008.3 The National Agricultural Statistics Service collected in-depth 2008 data about organic agriculture in the U.S. as a follow up to the 2007 agricultural census.4 The survey included farms that were certified organic, transitioning to organic and exempt from certification.5 The 2008 USDA Organic Agriculture Census illustrates that Wisconsin has a well-rounded organic portfolio, ranking highly in number of farms and sales for a diverse range of agricultural products. Number of organic farms Top five states in number of organic farms The 2008 USDA Organic Agriculture Census ranks Wisconsin second in California 2,714 total number of organic farms (Figure 1). The census reports 2,714 organic Wisconsin 1,222 farms in California, which is the top- Washington 887 ranked state, and 1,222 organic farms in Wisconsin. New York 827 Wisconsin is also in the top five states for organic acreage, with a total of Oregon 657 195,603 acres. -

Agricultural Campus

Agricultural Campus Cultural Landscape Inventory December 2005 (Revisions December 2011) Quinn Evans|Architects University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Landscape Architecture, College of Agricultural and Life Sciences Division of Facilities Planning and Management ©2011, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System University of Wisconsin-Madison Cultural Landscape Inventory DEFINITIONS What is a “cultural landscape”? The following document is based on concepts and techniques developed by the National Park Service. The NPS has produced a series of manuals for identifying, describing, and maintaining culturally significant landscapes within the national park system.1 The National Park Service defines a cultural landscape as a geographic area, including both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife or domestic animals therein[,] associated with a historic event, activity, or person, or [one] that exhibits other cultural or aesthetic values.2 In 1925, geographer Carl Sauer (1889-1975) summarized the process that creates cultural landscapes: “Culture is the agent, the natural area is the medium, the cultural landscape the result.” 3 Similarly, the writer J. B. Jackson (1909-1996) looked upon the landscape as a composition of spaces made or modified by humans “to serve as infrastructure or background for our collective existence.”4 What is a “cultural landscape inventory”? 5 This cultural landscape inventory for the agricultural campus is one of eight such studies completed as part of the UW-Madison Cultural Landscape Resource Plan. Each inventory defines the boundaries of a distinct cultural landscape on campus, summarizes its history, describes its current condition, and makes recommendations about its treatment. In addition to these eight cultural landscape inventories, two companion documents address the archaeology and overall history of the campus. -

Organic Agriculture in Wisconsin: 2017 Status Report

ORGANIC AGRICULTURE IN WISCONSIN: 2017 STATUS REPORT Prepared by the UW-Madison Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems and the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection Authors: Lisa Bauer, Cris Carusi, Anders Gurda, Ruth McNair and Erin Silva February 2017 2017 STATUS REPORT i This report is a joint effort of: The Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems (CIAS) is a research center for sustainable agriculture in the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison. CIAS fosters multidisciplinary inquiry and supports a range of research, curriculum and program development projects. It brings together university faculty, farmers, policy makers and others to study relationships between farming practices, farm profitability, the environment and rural vitality. For more information, visit www.cias.wisc.edu or call 608-262-5200. The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) works to make Wisconsin a world leader in agriculture, food safety and consumer protection. DATCP is responsible for food safety, animal and plant health, protecting water and soil, and monitoring fair and safe business practices. The DATCP Organic Agriculture Program is housed in the Division of Agricultural Development and provides individual technical assistance and education to organic farmers and those wishing to begin farming organically, as well as to businesses processing organic products. For more information, visit datcp.wi.gov or call 608-224-5095. The findings and policy recommendations in this resource are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection. Media contact: Cris Carusi, CIAS: [email protected] or 608-262-8018 Authors: Lisa Bauer, Cris Carusi, Anders Gurda, Ruth McNair and Erin Silva Publication design and layout by Ruth McNair, CIAS Editorial review provided by Kevin Kiehnau, Matt Nitz, Gene Schriefer and Steve Ventura This report is printed on recycled paper. -

Overview of Wisconsin Agriculture

Overview of Wisconsin Agriculture AAE 320: Farming Systems Management Paul Mitchell Learning Goals To become aware of 1. Major agricultural products Wisconsin farmers grow and their relative importance nationally 2. Economic impact of agriculture in Wisconsin 3. Current trends occurring among Wisconsin farms FARMER CASH RECEIPTS IN 2018 TOP 10 US STATES ($ BILLION) 50 40 WI $11.0 billion in 2018 30 20 10 0 Wisconsin is a Major Dairy State (2018) Dairy WI Rank % US #1 State Milk production 2 14.1 California Cheese, total 1 26.3 Wisconsin American 1 19.5 Wisconsin Cheddar 1 18.8 Wisconsin Hispanic 2 29.9 California Italian 1 31.1 Wisconsin Mozzarella 2 26.2 California Dry whey (food) 1 32.6 Wisconsin Wisconsin’s Place in US Agriculture (2018) Livestock WI Rank % US #1 State Cattle and calves 9 3.6 Texas Milk cows 2 13.6 California Hogs and Pigs 20 0.4 Iowa Sheep 20 1.4 Texas Milk Goats 1 16.7 Wisconsin Chickens 17 1.7 Iowa Broilers 20 0.6 Georgia Eggs 16 1.9 Iowa Mink Pelts 1 31.3 Wisconsin Honey 16 1.5 North Dakota Trout 6 1.0 Idaho Wisconsin’s Place in US Agriculture (2018) Grain/Feed Crops WI Rank % US #1 State Corn for grain 10 3.8 Iowa Corn for silage 1 11.0 Wisconsin Oats 4 9.8 North Dakota Soybeans 14 2.3 Illinois Wheat, winter 19 1.2 Kansas Forage (all types) 4 8.1 Texas Wisconsin’s Place in US Agriculture (2018) Vegetable Crops WI Rank % US #1 State Potatoes 3 6.0 Idaho Sweet Corn 3 13.1 Washington Green Peas 3 19.3 Washington Snap Beans 1 37.5 Wisconsin Carrots 3 5.2 California Cabbage 6 6.9 California Cucumber 7 4.0 Florida Pumpkins -

Urban Agriculture in Wisconsin: a Survey and Discussion of Land Use and Planning Practices in High Density Counties

URBAN AGRICULTURE IN WISCONSIN: A SURVEY AND DISCUSSION OF LAND USE AND PLANNING PRACTICES IN HIGH DENSITY COUNTIES Tim Kuhn, J.D. Candidate, University of Wisconsin Law School for Family Farm Defenders of Madison, Wisconsin December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction [need more Wisconsin stuff in the intro].......................................... 1 II. What is urban agriculture, and why is it important?............................................ 2 a. Breaking down traditional conceptions. ................................................................. 2 b. The Possibilities. ..................................................................................................... 3 c. The Problems we face. ............................................................................................ 5 III. Land Use Tools that can support Urban Agriculture ........................................... 7 a. Zoning ..................................................................................................................... 8 b. Comprehensive Plans .............................................................................................. 9 c. Conservation Easements/Purchase of Development Rights ................................. 10 d. Land Trusts ........................................................................................................... 11 IV. The Urban Agriculture Climate in Wisconsin ..................................................... 12 a. Municipal Zoning Ordinances ............................................................................. -

The New Normal Predicting Climate Impacts and Building Resilient Communities

The New Normal Predicting climate impacts and building resilient communities join us: Acknowledgements The primary funding for this work was generously provided by the Joyce Foundation. Additional support for Clean Wisconsin’s climate program work is provided by the Garfield Foundation. Lead Author: Katy Walter, Clean Energy Specialist, Clean Wisconsin Several Clean Wisconsin staffers assisted with this report. Special thanks to: Keith Reopelle, Senior Policy Director Amanda Wegner, Creative Director Tyson Cook, Staff Scientist Sam Weis, Communications Director About Clean Wisconsin Clean Wisconsin is an environmental advocacy organization that works to protect Wisconsin’s clean water and air and advocates for clean energy by being an effective voice in the state legislature and by holding elect- ed officials and polluters accountable. Clean Wisconsin was founded in 1970 as Wisconsin’s Environmental Decade and is the state’s largest environmental advocacy organization. page 2 The New Normal Preparing for the New Normal Unprecedented warm spring temperatures interrupt on many facets of life in Wisconsin. Agriculture and Wisconsin’s annual spring maple syrup harvest, leaving outdoor recreation, two prime areas susceptible to a the industry hurting from a 68% decline in production. changing climate, are critical to our way of life and key Cherry farmers from Door County and apple farmers pillars of our economy. Unfortunately, we are already in Bayfield watch helplessly as their fruit trees blos- beginning to see major impacts in these areas. Wiscon- som early, only to be destroyed by frost. In the midst of sin is experiencing the sharpest increase in severe rain1 one of the worst droughts in memory, corn farmers in and is among the states that are warming at the fastest southern Wisconsin hope for rain to save their crops, rate2; Climate Central ranked Wisconsin No. -

Organic Agriculture in Wisconsin: 2012 Status Report

2012 STATUS REPORT ORGANIC AGRICULTURE IN WISCONSIN: 2012 STATUS REPORT Prepared by the UW-Madison Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems and the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection Authors: Erin Silva, Laura Paine, Matt Barnidge, Cris Carusi and Ruth McNair February, 2012 i ORGANIC AGRICULTURE IN WISCONSIN This report is a joint effort of: The Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems (CIAS) is a research center for sustainable agricul- ture in the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison. CIAS fosters multidisciplinary inquiry and supports a range of research, curriculum and program development projects. It brings together university faculty, farmers, policy makers and others to study relationships between farming practices, farm profitability, the environment and rural vitality. For more informa- tion, visit www.cias.wisc.edu or call 608-262-5200. The Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) works to make Wisconsin a world leader in agriculture, food safety and consumer protection. DATCP is re- sponsible for food safety, animal and plant health, protecting water and soil, and monitoring fair and safe business practices. The DATCP Organic Agriculture Program is housed in the Division of Agri- cultural Development and provides individual technical assistance and education to organic farmers and those wishing to begin farming organically, as well as to businesses processing organic products. For more information, visit datcp.state.wi.us or call 608-224-5120. Media contact: Cris Carusi, CIAS: [email protected] or 608-262-8018 Authors: Erin Silva, Laura Paine, Matt Barnidge, Cris Carusi and Ruth McNair Edited by Cris Carusi and Ruth McNair, CIAS. -

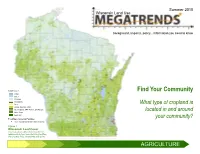

Find Your Community

Summer 2010 Wisconsin Land Use background, impacts, policy…information you need to know Land Cover Find Your Community Urban Water Wetlands Woodlands Corn What type of cropland is Grains, Hay and Alfalfa Idle Cropland, CRP, Fallow, and Pasture located in and around Other Crops Soybeans Food Manufacturing Facilities your community? Fruit, Vegetable and Grain Manufacturing Figure 1 Wisconsin Land Cover This map shows Wisconsin cropland1 in relationship to food manufacturing facilities that process fruits, vegetables and grains.2 AGRICULTURE 1 U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2009 Cropland Data Layer. www.nass.usda.gov/ Statistics_by_State/Wisconsin/Publications/Cropland_Data_Layer/2009/index.asp 2 U.S. Census Bureau. 2007 North American Industry Classification System. Food Manufacturing. www.census.gov/cgi-bin/sssd/naics/naicsrch?chart=2007 2 AGRICULTURE The Changing Face of Wisconsin Agriculture Historic Farmland Trends Figure 2 Farm Size and Diversity Wisconsin Farm Trends, 1950-2008 Wisconsin‘s history is closely tied with agriculture. In The number of farms in Wisconsin peaked at just under 200,000 Wisconsin farms are diverse, differing in size, value of in 1935. Since that time, the number of farms and total amount of 1848, when the state was founded, two out of every farmland in the state has steadily declined. Meanwhile, average sales, products produced, marketing techniques, land three residents lived on a farm.3 At that time, the state‘s farm size has grown, peaking in the early 1990s.4 management practices, technology, employment, 20,000 farms averaged less than 100 acres each. By 250 ownership structure, and other characteristics. the start of World War I, farming became quite profitable.