Lectures in Canadian Labour and Working-Class History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of the Wagner Act: a Canadian-American Comparison

The Future of the Wagner Act: A Canadian-American Comparison Brian WBurkett* Although the Wagner model has served as a basisfor both Canadian andAmerican labour law since the 1950s, recent politicaland legal debates have questioned its continued viability in each country. These debates give the impression that while the Wagner model is virtually obsolete in the United States, it remains quite viable in Canada. The author challenges this impression and suggests that the Wagner model may not be as well-entrenched in Canadaas it seems to be. The authorfirst traces the development of Canadian and American labour law in the twentieth century and the different circumstances surrounding the Wagner model's adoption in the two countries. The author then compares the current state of the model in both countries, highlighting such important differences as Canada's much broader acceptance of public sector collective bargainingand of labourrelations boards as an impartialand effective adjudicative forum. In support of this concern about the Wagner model's future in Canada, the authorpoints to recent jurisprudence under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to the effect that although the right to freedom of association protects the right of workers to a meaningful workplace dialogue with their employer, it does not constitutionalize the specific elements of the Wagner model. The authorargues that these cases and certain recent government initiatives suggest that courts and legislatures may be displacing labour relations boards as the primary forum for resolving labour disputes. Even more importantly, jurisprudencehas made it clear that legislators are free to consider alternatives to the Wagner model, thereby adding to the uncertainty about the model'sfuture role in Canadian labourlaw. -

Canadian Journal Ofpolitical and Social Theory/Revue Canadienne De Theorie Politique Etsociale, Vol

Canadian Journal ofPolitical and Social Theory/Revue canadienne de theorie politique etsociale, Vol . 3, No . 2 (Spring-Summer/Printemps-Ere, 1979) . THE WESTERN CANADIAN LABOUR MOVEMENT, 1897-1919 H. Clare Pentland The objective of this essay is to establish and clarify the dimensions, the character, and the significance of the remarkable labour movement that developed in western Canada in the closing decades of the nineteenth century and flourished during the great boom of the early twentieth . Within this general purpose are some particular ones: to demonstrate the rapidity of the numerical growth of unionism in the West, to suggest some reasons for it, and to show why western unionists were far more radical and militant than eastern ones. It is a capital fact, if an obvious one, that the labour movements of western Canada and the western United States had marked similarities and inter- relationships in this period. Both displayed a radicalism, a preference for in- dustrial unionism, and a political consciousness that differentiated them sharply from their respective Easts. It seems apparent that the labour forces of the two Wests were shaped by similar western forces that need to be identified - the more so because hostile eastern craft unionists and their scholarly apologists have tended to misunderstand these forces. However, it is no less important to remark (and this, too, has been sometimes confused) that the labour movement of western Canada was no simple offshoot or branch-plant of unionism in the western United States. In fact, the Canadian movement was clearly differentiated from its American counterpart in various ways, particularly by its (relatively) greater size, cohesion, power, and political effectiveness . -

And Others TITLE in Search of Canadian- Materials

DOCUAENT EBSUBB ED 126 351 CB 007 4890 AUTHOV Phillips, Donna; Coop.; And Others TITLE In Search of Canadian- Materials. INSTITUTION Hanitoba Dept. of Education, Hinnipeg. PUB DATE Apr 76 NOTE 213p. EDRS PRICE OF -$0.83 BC-$11.37 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Annotated 'Bibliographies; Audiovisual Aids; Books; *Elementary Secondary Education; *Foreign Countries; *Library Haterial Selection; Periodicals;Reference Materials; Resource Haterials; *SchoolLibraries tZENTIFIERS *Canada; '}Manitoba ABSTRACT The annotated bibliography, commissioned by the Canadian Studies Project. Committee, isa basic list of available Canadian materials suitable for school libraries.It consists of over 1,000 entries withan emphasis on materials ,relevant to Manitoba.A broad range of topics is covered: business education,e consumer eduegation, fine arts, guidance, familylife and health, hope economics, language and literature (biography,drama, novels, short stories, folktales, language arts, miscellaneous,picture books and picture story books, and poetry), literarycriticism, mathematics, physical education, social studies (geography,history, native studies, and 4sobitical studies), and science(general, physical, and natural). The majority of items listedare library or trade books but some text book series, periodicals, and reference materialshave been included. All types of audiovisual materialsare included except 16mb films and videotapes. For each entry typicalbibliographical data, grade level, and a brief description,are included. A title index is appended. (BP) ********************************************************************** DocAtheAts acquired by ERIC includemany informal unpublished * materials not available `from othersources. ERIC cakes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless,items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and thisaffects the quality * * of the picrofiche and hardcopy reproductionsERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Docutent Reproduction Service (EbRS).EDRS is not * * responsible for the quality of the originaldocument. -

PRAIRIE F DRUM Vol

PRAIRIE F DRUM Vol. 18, No.2 Fall 1993 CONTENTS ARTICLES The Rise of Apartmentsand Apartment Dwellers in Winnipeg (1900-1914)and a Comparative Studywith Toronto Murray Peterson 155 Pre-World War I Elementary Educational Developmentsamong Saskatchewan'sGerman Catholics: A Revisionist View ClintonO, White 171 "The El Dorado of the Golden West": Blairmore and the WestCanadian Collieries, 1901-1911 Allen Seager 197 War, Nationhood and Working-Class Entitlement: The Counterhegemonic Challenge of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike Chad Reimer 219 "To Reach the Leadership of the Revolutionary Movement": A~J. Andrews, the Canadian State and the Suppression of the WinnipegGeneral Strike Tom Mitchell 239 RESEARCH NOTES .~---~--_.~------ _.- ---- Images of the Canadian West in the Settlement Era as Expressed in Song Texts of the Time R. Douglas Francis andTim B. Rogers 257 TheJune 1986Tornado of Saskatoon: A Prairie CaseStudy R.E. Shannon and A.K. Chakravarti 269 REVIEWS FRANCIS, R. Douglasand PALMER, Howard, eds., The Prairie West: Historical Readings by James M. Pitsula 279 COATES, Kenneth S. and MORRISON, William R., eds., liMy Dear Maggie ...":Letters from a Western Manitoba Pioneer by Patricia Myers 282 CHARTRAND, Paul L.A.H., Manitoba's Metis Settlement Scheme of1870 by Ken Leyton-Brown 283 CHORNEY, Harold and HANSEN, Phillip, Toward aHumanist Political Economy by Alvin Finkel 286 POTVIN, Rose, ed., Passion and Conviction: The Letters ofGraham Spry by Frank W. Peers 289 RUSSELL, Dale R., Eighteenth-Century Western Cree and Their Neighbours by David R. Miller 291 TUPPER, Allan and GIBBINS,Roger, eds., Government and Politics in Alberta by David Laycock 294 CONTRIBUTORS 299 ---------------- -~-~-~-------_.._- PRAIRIE FORUM:Journal of the Canadian Plains Research Center Chief Editor: Alvin Finkel, History, Athabasca Editorial Board: I. -

Labor Archives in the United States and Canada

Labor Archives in the United States and Canada A Directory Prepared by the Labor Archives Roundtable of the Society of American Archivists This directory updates work done in the early 1990s by the Wagner Labor Archives in New York City. A survey then conducted identified "archivists, librarians, and labor union staff who are collecting manuscripts, audio-visual materials, and artifacts that document the history of the trade union movement in the United States." Similarly, this directory includes repositories with partial holdings relating to labor and workers, as well as repositories whose entire holdings pertain to labor. The most recent updates were made in 2011; previously known updates were made in 2002. The directory is organized by state, then by repository, with Canadian repositories listed last. Please contact officers of the Labor Archives Roundtable, Society of American Archivists, if you have additions, comments, corrections, or questions. Labor Archives in the United States and Canada 1 Alabama Alabama Labor Archives http://www.alabama-lah.org The Alabama Labor Archives and History is a private not-for-profit corporation that began in 2002 when the Alabama AFL-CIO recognized the need for a labor archives and history museum that showed the progress of organized labor in Alabama. The mission of the Alabama Labor Archives and History is to identify, evaluate, collect, preserve, and provide access to material of labor significance in Alabama. Birmingham Public Library, Archives Department http://www.bplonline.org/locations/central/archives/ The collection includes charters, records, scrapbooks and other material relating to various Birmingham, Alabama, labor unions, papers of individuals involved in the labor movement, oral history interviews, research files, and photographs. -

CE 004 499 Bias in Textbooks Regarding the Aged, Labour

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 110 705 CE 004 499 AUTHOR Babin, Patrick TITLE Bias in Textbooks Regarding the Aged, Labour Unions, and Political Minorities. INSTITUTION Ottawa Univ. (Ontario). Faculty of Education. SPONS AGENCY Ontario Dept. of Education, Toronto. PUB DATE 30 Jan 75 NOTE 194. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$9.51 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Foreign Countries; *Labor Unions; Literature Reviews; *Minority Groups; *Older Adults; *Textbook Bias IDENTIFIERS Canada ABSTRACT The report opens with detailed summaries of historical background information for each of the groups involved and with a review of the literature on bias in textbooks in Canada, the United States, and other countries. Over a time span of six months, 211 readers evaluated 1,719 textbooks. Readers located 104 biases in 78 textbooks. The 23 biases against the aged occurred mainly in English primary texts. Bias by omission accounted for most of the 65 findings concerning labor unions; however, strong negativestatements about unions constituted most of the other biases. The 16 biases against political minorities were mostly ones of omission. The investigltors believed that biases against labor unions could havea strong negative effect on student attitudes. Biases regarding the aged and political minorities, on the other hand, were not considered pronounced enough to negatively affect student attitudes. The investigators recommended objective balanced treatment of minority groups in textbooks, and the formulation of guidelines for textbook evaluation. Seven appendixes include the evaluation instrument; related biases against the French, Indians, other ethnic minorities, and women; suggestions for improving the evaluation instrument; and lists of texts containing bias. (JR) *********************************************************************** * Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * *materials not available from other sources. -

TRACES of MAGMA an Annotated Bibliography of Left Literature

page 1 TRACES OF MAGMA An annotated bibliography of left literature Rolf Knight Draegerman Books, 1983 Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada page 2 Traces of Magma An annotated bibliography of left literature Knight, Rolf Copyright © 1983 Rolf Knight Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0-86491-034-7 1. Annotated bibliography 2. Left wing literature, 20th century comparative Draegerman Books Burnaby, British Columbia, V5B 3J3, Canada page 3 Table of Contents Introduction 5 Canada, United States of America, Australia / New Zealand 13 Canada 13 United States of America 24 Australia and New Zealand 51 Latin America and the Caribbean 57 Mexico 57 Central America 62 Colombia 68 Venezuela 70 Ecuador 71 Bolivia 74 Peru 76 Chile 79 Argentina 82 Uruguay 85 Paraguay 86 Brazil 87 Caribbean-Spanish speaking 91 Dominican Republic 91 Puerto Rico 92 Cuba 93 Caribbean- Anglophone and Francophone 98 Europe: Western 102 Great Britain 102 Ireland 114 France 118 Spain 123 Portugal 131 Italy 135 Germany 140 Austria 151 Netherlands and Flanders 153 Denmark 154 Iceland 157 Norway 159 Sweden 161 Finland 165 Europe: East, Central and Balkans 169 U.S.S.R .(former) 169 Poland 185 Czechoslovakia (former) 190 Hungary 195 Rumania 201 Bulgaria 204 Yugoslavia (former) 207 Albania 210 Greece 212 page 4 Near and Middle East, North Africa 217 Turkey 217 Iran 222 Israel 225 Palestine 227 Lebanon, Syria, Iraq 230 Egypt 233 North Africa and Sudan 236 Sub-Saharan Africa 241 Ethiopia and Somalia 241 Francophone Africa 244 Anglophone Africa 248 Union of South Africa 253 Mozambique and Angola 259 India and Southeast Asia 262 India 262 Pakistan 274 Sri Lanka, Burma, Thai1and 275 Viet Nam 277 Malaya 279 Indonesia 281 Phi1ippines 284 East Asia 288 China 288 Korea 296 Japan 299 Bibliographic Sources 311 Authors’ Index 330 page 5 INTRODUCTION This is basically an annotated bibliography of left wing novels about the lives of working people during the 20th century. -

Corporate Policing, Yellow Unionism, and Strikebreaking, 1890–1930

Corporate Policing, Yellow Unionism, and Strikebreaking, 1890–1930 This book provides a comparative and transnational examination of the complex and multifaceted experiences of anti-labour mobilisation, from the bitter social conflicts of the pre-war period, through the epochal tremors of war and revolution, and the violent spasms of the 1920s and 1930s. It retraces the formation of an extensive market for corporate policing, privately contracted security and yellow unionism, as well as processes of professionalisation in strikebreaking activities, labour espionage and surveillance. It reconstructs the diverse spectrum of right-wing patriotic leagues and vigilante corps which, in support or in competition with law enforcement agencies, sought to counter the dual dangers of industrial militancy and revolutionary situations. Although considerable research has been done on the rise of socialist parties and trade unions the repressive policies of their opponents have been generally left unexamined. This book fills this gap by reconstructing the methods and strategies used by state authorities and employers to counter outbreaks of labour militancy on a global scale. It adopts a long-term chronology that sheds light on the shocks and strains that marked industrial societies during their turbulent transition into mass politics from the bitter social conflicts of the pre-war period, through the epochal tremors of war and revolution, and the violent spasms of the 1920s and 1930s. Offering a new angle of vision to examine the violent transition to mass politics in industrial societies, this is of great interest to scholars of policing, unionism and striking in the modern era. Matteo Millan is associate professor of modern and contemporary history at the University of Padova, Italy. -

Download/9330/9385)

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Class Idea: Politics, Ideology, and Class Formation in the United States and Canada in the Twentieth Century Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/71m226ss Author Eidlin, Barry Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Class Idea: Politics, Ideology, and Class Formation in the United States and Canada in the Twentieth Century by Carl Boehringer Eidlin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Kim Voss, Chair Professor Neil Fligstein Professor Dylan Riley Professor Margaret Weir Professor Paul Pierson Fall 2012 Abstract The Class Idea: Politics, Ideology, and Class Formation in the United States and Canada in the Twentieth Century by Carl Boehringer Eidlin Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Kim Voss, Chair Why are class politics more prevalent in Canada than in the U.S., even though the two countries share similar cultures, societies, and economies? Many view this cross-border distinction as a byproduct of long-standing differences in political cultures and institutions, but I find that it is actually a relatively recent divergence resulting from how the working class was politically incorporated in both countries before, during, and after World War II. My central argument is that in Canada, this incorporation process embedded “the class idea”—the idea of class as a salient, legitimate political category— more deeply in policies, institutions, and practices than in the U.S. -

Worker Voice: Employee Representation in The

Worker Voice Employee Representation in the Workplace in Australia, Canada, Germany, the UK and the US 1914–1939 STUDIES IN LABOUR HISTORY 5 Studies in Labour History ‘...a series which will undoubtedly become an important force in re-invigorating the study of Labour History.’ English Historical Review Studies in Labour History provides reassessments of broad themes along with more detailed studies arising from the latest research in the ield of labour and working-class history, both in Britain and throughout the world. Most books are single-authored but there are also volumes of essays focussed on key themes and issues, usually emerging from major conferences organized by the British Society for the Study of Labour History. he series includes studies of labour organizations, including international ones, where there is a need for new research or modern reassessment. It is also its objective to extend the breadth of labour history’s gaze beyond conven- tionally organized workers, sometimes to workplace experiences in general, sometimes to industrial relations, but also to working-class lives beyond the immediate realm of work in households and communities. Worker Voice Employee Representation in the Workplace in Australia, Canada, Germany, the UK and the US 1914–1939 Greg Patmore LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS To Helen, Julieanne, Robert and James Worker Voice First published 2016 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2016 Greg Patmore he right of Greg Patmore to be identiied as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. -

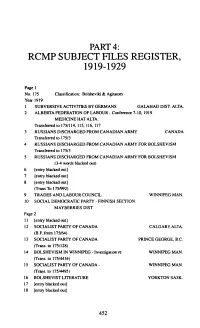

Part 4: Rcmp Subject Files Register, 1919-1929

PART 4: RCMP SUBJECT FILES REGISTER, 1919-1929 Page 1 No. 175 Classification: Bolsheviki & Agitators Year 1919 1 SUBVERSIVE ACnVmES BY GERMANS GALAHAD DIST. ALTA. 2 ALBERTA FEDERATION OF LABOUR - Conference 7-10, 1919 MEDICINE HAT ALTA. Transferred to 175/114, 115, 116, 117 3 RUSSIANS DISCHARGED FROM CANADIAN ARMY CANADA Transferred to 175/3 4 RUSSIANS DISCHARGED FROM CANADIAN ARMY FOR BOLSHEVISM Transferred to 175/3 5 RUSSIANS DISCHARGED FROM CANADIAN ARMY FOR BOLSHEVISM (3-4 words blacked out) 6 [entry blacked out] 7 [entry blacked out] 8 [entry blacked out] (Trans To 175/992) 9 TRADES AND LABOUR COUNCIL WINNIPEG MAN. 10 SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY - FINNISH SECTION MAYBERRIES DIST Page 2 11 [entry blacked out] 12 SOCIALIST PARTY OF CANADA CALGARY ALTA. (B.F from 175/64) 13 SOCIALIST PARTY OF CANADA PRINCE GEORGE, B.C. (Trans, to 175/128) 14 BOLSHEVISM IN WINNIPEG - Investigation re WINNIPEG MAN. (Trans, to 175/4434) 15 SOCIALIST PARTY OF CANADA - WINNIPEG MAN. (Trans, to 175/4495) 16 BOLSHEVIST LITERATURE YORKTON SASK. 17 [entry blacked out] 18 [entry blacked out] 452 RCMP SUBJECT FILES REGISTER. 19I9-I929 453 19 [1-2 wofds Hacked out]-letter to Calgaiy Herald 20 [2-3 wofds blacked out] Seditious actions of VANCOUVER B.C. Page 3 21 [entry blacked out] 22 (entry blacked out] (Trans, to 175/123) 23 BADKA, Bishop of Ukrainian Church WINNIPEG MAN. 24 [entry blacked out] 25 [entry blacked out] 26 [entry blacked out] 27 ANTI-BOLSHEVIK RIOTING IN JAN 26.1919 WINNIPEG MAN. 28 [entry blacked out] 29 [entry blacked out] (Trans, to 175/446) 30 BOLSHEVIK ACTIVITIES - Situation at coal mines CARDIFF ALTA. -

The Fighting Machinists

A Century of Struggle by Robert G. Rodden Formatted and made available electronically by William LePinske Cover design by Elaine Poland and Charlie Micallef "Without machinists there could be no machines; they make the die and the basic tools from which the machines are made. From the initial blueprint the machinist fashions the original tool-the first step in the process. His is the essential skill at the core. He holds the key that unlocks the mystery of the mechanical age. He makes the miracle." Tom Tippett IAM Director of Education 1947-1956 1 God watches over Drunks, Old Ladies, Little Children and The International Association of Machinists (Old Machinists saying) ... And if he won't fight he ain't a Machinist. (Printable part of another, even older Machinists saying) 2 Dedication The history of the Machinists Union is dedicated to a unique brotherhood of roving machinists who were known as boomers. They knew each other by such names as Dutchy Bigelow, Milwaukee Bill, Fireball McNamara and Red Clifford . Texas Frank, Black Jack Roberts, Windy Lane and Silverheel Smith… Crusty Paulson, Happy Anderson, Big Nose Brennan and Steampipe McDermott . Smoky Davis, Silk Hat John Kelly, Yankee Tim Sullivan and Hard Luck Bob Carson . Gabby Cook, Shanty Frank Shannon, Pittsburgh Murphy and Highball Mooney . Kid Richardson, Deacon Hague, Pay Day Conners and Scarface Charlie. It is dedicated to these and all the other unknown, unsung, and unremembered boomer machinists who fought, cussed, drank, rode the rails . and built a union. But most of all it is dedicated to Pete Conlon…the greatest boomer of them all.